The legendary lawyer, the youngest prosecutor at the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal, initiated and conducted the largest mass murder case – the Einsatzgruppen Trial. To find out how he obtained the evidence – the scrupulous reports on the extermination of “Untermenschen” in the occupied territories of the USSR, compiled by the Nazis themselves – read here, and here about who was brought before the international tribunal at the 9th subsequent Nuremberg trial.

CHAPTER 5. THE PROCESS

Sadness and Hope

Of the twenty-four defendants, two dropped out of the trial prematurely. Emil Haussmann, shortly after being indicted along with all the others, committed suicide in his cell on 31 July 1947. Dr Otto Rasch escaped punishment because he was seriously ill. One day Hans Zurholt (Rasch's legal counsel) appeared in Ben's office and asked to drop the charges against his client, who suffered from Parkinson's disease or shaking palsy. “If I killed as many people as he did, I'd be shaking too”, Ben replied. As long as Rasch was breathing, he would not let him escape trial. At the start of the trial, the former commanding officer of Einsatzgruppe C was brought into the hall on a stretcher. But his growing weakness due to illness saved him from being sentenced. Rasch was released from custody on 5 February 1948 and died nine months later.

The trial began on 15 September 1947 in Courtroom 600 of the Nuremberg Palace of Justice with the reading of an indictment in the tradition of Anglo-Saxon criminal procedure. For all the defendants it consisted of three counts: crimes against humanity, war crimes, and participation in organisations recognised as criminal. The defendants were asked whether they were aware of these charges, whether they understood them, and whether they pleaded "guilty" or "not guilty". Although the gravity of the evidence was overwhelming, everyone claimed to be innocent of the crimes.

The main part of the trial began two weeks later, on 29 September, when Ben Ferencz opened the hearing by filing an indictment. In the wood-panelled courtroom, where two years earlier the trial against top Nazi leaders had taken place, a legal drama of unprecedented proportions unfolded. The AP news agency reported about the "biggest murder trial in history" and the "worst murderers in history". Behind a massive wooden barrier on the dais were the benches for the defendants. In front of them, a few steps below, sat their legal counsels, mostly former members of the Nazi Party. Three US judges, dressed in black robes, sat at the table opposite. Behind their backs was an American flag, the star-spangled banner. The representatives of the prosecution moved to the side and took up space in the middle, forming a kind of triangle with the judges and the defendants. The world's press and the public, including Gertrude, watched from the back rows. Each seat was equipped with headphones and simultaneous interpretation was provided between English and German.

The atmosphere in the hall, according to Ben, was “calm and very concentrated”: “There was no applause, no booing, no laughter, nothing”. There were hardly any Germans in the audience. The trials that followed were of far less interest to them than the trial of Göring and the other major Nazi criminals. The relatives of the victims were also rarely present. The defendants were heavily guarded: they were brought in a lift from an escort room underneath the courtroom directly to the dock, under the supervision of US military police.

The presiding judge, Michael Musmanno, gave the floor to Ben. In a calm, steady voice he read out a statement, glancing from the script to the audience. As Ben looked to his left, he saw the defendants sitting with sullen faces, but looking “perfectly normal”. When asked what it was like to face the mass murderers, Ben replied: “There was no reaction from them or me. I never once raised my voice or snapped. I remained icy calm”. All that mattered to him were the facts documented in the Einsatzgruppen reports. To avoid distractions and emotions, Ben learned nothing about the personal lives of the criminals and tried not to cross paths with them outside the courtroom.

There was an incident in the courtroom involving defendant Strauch. He rose from the bench and suddenly disappeared from view. The military guards rushed towards him with their batons raised: crouched down, Strauch was lying on the floor - he appeared to have had an epileptic, or possibly a psychogenic, seizure.

In his “opening speech on behalf of the United States of America”, Ben impartially outlined the main features of the case from the prosecution's point of view. After a general introduction, he spoke about the ideological motives behind the crimes in question, the structure and organisation of the Einsatzgruppen, some of the operations, the legal basis for the trial, the three counts of prosecution and, finally, the personal responsibility of the criminals.

The young chief prosecutor was aware of the historical significance of this moment. With his first phrase (which is not found in the old newsreels; the footage began immediately after these remarks), he gave the tribunal a lofty perspective: “When we uncover here the premeditated murder of over a million innocent and defenceless men, women, and children, it overwhelms us with sadness and hope”. These words reflect his approach to the process: he was faced with a task "far more important than catching a handful of killers", as he has said over the years. Revenge was not the goal, nor was equalising justice, he stressed in his speech. He was convinced that such a thing could not even exist: you cannot undo an injustice by making up for the murder of over a million people with the lives of two dozen criminals. But a tribunal can help - and he is certain of this - to prevent similar horrors in the future. It should lay the groundwork for a more peaceful life. The case he brought to trial must "call humanity to the law". International law enforcement must be strengthened to protect everyone's rights to live in peace and dignity, regardless of race or religion.

The SS Einsatzgruppen, the elite command of murderers in uniform, trampled over all concepts of law. They were created for the specific purpose of exterminating people simply because they were Jewish or, in the view of the Nazis, inferior for some other reason. The reports of the Einsatzgruppen showed that the mass murders committed by the defendants were not motivated by military necessity, but by the Nazis' pseudo-Darwinian theory of the Übermensch (superhuman – ed. note). These actions were the deliberate implementation of far-reaching plans to eliminate undesirable ethnic, national, political, and religious groups.

Ben introduced a new term – “genocide” - into legal parlance for this process. What today is a common term and the subject of a widely recognised UN Convention was, at the time, still unknown. “Genocide, the extermination of entire categories of people, was a central tool of the Nazi doctrine”, he said. One of the counts of the indictment (crimes against humanity) accused the SS of systematically working towards this end. The term "genocide" originated with Polish refugee and lawyer Raphael Lemkin. Ben met him in the halls of the Nuremberg Palace of Justice where Lemkin, who had already assisted Robert Jackson, the chief US prosecutor at the International Military Tribunal in 1945-1946 - with eyes filled with horror - told his fate to anyone who would listen. His entire family was massacred by the Nazis. Out of respect for him and the validity of his legal arguments, Ben included the term in his Nuremberg speech.

The prosecution had two objectives: to create a global legal order to protect against persecution and extermination, and to carry out the American re-education policy. "Germany is a country lying in ruins and occupied by foreign troops, with a crippled economy and a starving population”, Ben reminded. Most Germans were still unaware of the events being dealt with here. But they had to know what was going on, to understand the reasons for their current poverty. Then a "genuine ideal" could take the place of their insane fetish.

Ferencz made it clear that the systematic killings by the SS Einsatzgruppen were justified by the National Socialist racial theory formulated by Alfred Rosenberg. The doctrine of Aryan superiority and the inferiority of other nations became an entirely serious idea. At a briefing meeting shortly before the invasion of the Soviet Union, Heydrich and Bruno Streckenbach, the head of the Personnel Department of the RSHA, implored the leaders of the Einsatzgruppen that it was part of their mission to eradicate the enemies of National Socialism. By enemies, they meant communist commissars and Jews. Soon, however, the number of "enemies" entering the crosshairs was so great that they could not be rendered extinct by collateral measures. They had to be eliminated “en masse”.

Ferencz reminded the court that the Einsatzgruppen consisted of a maximum of 3,000 people, a small number compared to the more than one million victims (this was the number of people killed that the prosecution assumed and relied on). Those four groups killed an average of 1,350 people every day for two years.

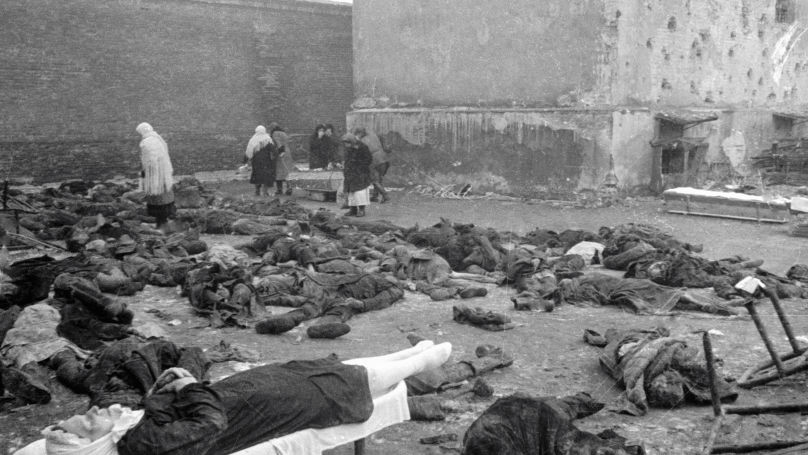

The enormous volume of "special treatment" required hard work and impeccable organisation. Murder squads willingly used deception: they spread false information about Jews being relocated. Instead, trucks carrying human cargo drove to execution sites outside cities. Shooting was the most common form of murder. In this context, Ben quoted the stirring testimony of German civilian Hermann Grebe, who witnessed a mass execution near Dubno in Ukraine on 5 October 1942. According to him, there were living people among the corpses in the pit. He estimated that about 1,000 bodies were piled on top of each other. The completely undressed victims climbed down a ladder carved into the clay wall of the pit and climbed over the heads of the executed men to the place to which the SS-man was pointing. With a cigarette in his mouth, he ordered people to lie down - and fired his machine gun. During the mass execution, the SS eliminated the entire Jewish population of the town, some 5,000 people.

Another method was to use specially converted trucks or vans that sent the exhaust gases inside the closed vehicle. When the vehicles arrived at their destination, most of the victims were dead, but among the twisted, blackened bodies there were some people that remained alive. They were pulled out and often somehow buried in mass graves. Money, jewellery, and other valuables were seized. The total amount of loot was scrupulously recorded in the reports sent to the main headquarters, as was the number of people killed.

Describing the scale of the massacres carried out by the Einsatzgruppen, Ben gave examples from documents. In October 1941, Einsatzgruppe A reported to Berlin the killing of some 121,817 people. Einsatzkommando 2 of Einsatzgruppe A, led by Eduard Strauch, committed a total of 33,970 murders in six months.

In mid-November 1941, just five months after the start of Operation Barbarossa, Einsatzgruppe B reported the killing of 4,5467 people. Ben presented to the court the sworn testimony of defendant Blume. The Standartenführer recounted how he had taken part in the executions at Vitebsk and Minsk. Seventy to eighty people were killed there each time. They were lined up in groups of about ten men in front of the pit and shot with carbines. The execution squad consisted of thirty to forty men. “This way there was no need for control shots”, Blume said.

Einsatzgruppe C also distinguished itself with horrifying reports of “success”. At the beginning of November 1941, it was reported that some 80,000 people had been exterminated by that time. The report was replete with the details of the extermination of Jews in Kiev. Immediately after the occupation of the city, "repressive measures" were taken against Jews and their families. The Jewish population was ordered to assemble for resettlement from Kiev. Contrary to expectations, not 5,000 to 6,000 people, but over 30,000 came to the gathering place. Thanks to skillful organisation, the Jews believed until the last moment that they were being resettled. In reality, the massacre of Babi Yar awaited them.

In this case, Paul Blobel, who was in charge of the operation, stood out conspicuously. "The murder of 33,000 Jews living in Kiev in just two days breaks every horrifying record among the Einsatzgruppen", Ben reported. Such an event is hard to imagine. But the Jews were by no means the only part of the population to be exterminated. Even if one hundred percent of the Jews could be immediately exterminated, this would not eliminate the source of the political danger, according to Einsatzgruppe C. The Bolshevik apparatus relied on Russians, Georgians, Armenians, Poles, Ukrainians, and others - all of whom were also targets for extermination, along with the disabled. Ben gave the example of the psychiatric hospital where Einsatzkommando 6 liquidated 800 people.

Ben referred to Einsatzgruppe D the last. The staff officers sat in the dock, he said, pointing to commanding officer Ohlendorf, the second-in-command Seibert, and adjutant Schubert. In nine months, the group destroyed more than 90,000 lives, shooting an average of 340 people a day. The victims included Jews, Roma, Asians, and other "undesirable" people.

The final part of Ben's speech focused on legal and moral issues. It was important for him to justify the legality and legitimacy of the court. He drew on the international agreements between the twenty-three states and the Allied Control Council Law No. 10 from 20 December 1945. The law provided the legal basis for the prosecution of crimes committed under National Socialism with state and party consent. Ben stressed that the US military tribunals over the Einsatzgruppen were international as well: “The murders in this case were committed in certain towns and villages, but the rights that the defendants violated apply to all people, universally”. Ferencz called the pirates and brigands of previous centuries "harbingers of modern international crime". Legal doctrine allowed states to punish them regardless of the nationality of the victims or the location of the crime. Ben quoted Sir Hartley Shawcross, the chief British prosecutor at the International Military Tribunal, as saying that the need to protect basic human rights against regimes that flagrantly violate them has long been recognised as part of international law. German professors have also written about this. In the notes to his speech, Ben referred to Johann Caspar Bluntschli and his work “Das moderne Völkerrecht Process 129 der civilisierten Staaten” (1868) ("The Modern International Law of Civilised States"). Bluntschli, one of the foremost jurists of his time, was Swiss but had made a career in Germany. When Ben urged the judges to consider the charges against the defendants "in the name of civilisation", he was inspired by the personality of Bluntschli, an expert in the origins of international law.

For that reason, Ben thought the charges of “crimes against humanity” and “war crimes” should be treated as different types of crimes. Even if the acts the defendants are accused of are identical in both cases, they are different criminal offences. To illustrate, he gave an example from common courts: if a robbery is accompanied by bodily harm, the law punishes both crimes. Here the principle is the same: the killing of defenceless civilians is a war crime, but at the same time it is part of another, larger act - genocide or a crime against humanity. The latter may take place both in wartime and in peacetime, and the criminal intent is directed "against the rights of all people" and not only against those in the conflict zone. To call such acts war crimes alone would be to "misjudge their motivation and true nature". Accordingly, the prosecution sees the central importance of this case as “protecting fundamental human rights by the rule of law”.

At the same time, Ben continued, saying the prosecution intends "to hold a handful of people accountable for actions they probably could not have committed alone". The question arises, he said, of how to measure their guilt. Ben pondered this, addressing not only the judges in black robes but also the defendants, who were following the German translation of his speech through headphones with serious still faces. "Everyone in the dock was fully aware of the purpose of their organisation", Ben said. All the accused held positions of responsibility or command in the punitive units. As warlords, they are bound by laws that are familiar to anyone who wears a uniform. This includes a legal and moral duty to prevent crime in their own area of responsibility. The fact that they were acting on orders from their government or commander does not absolve them of responsibility for criminal acts.

The chief prosecutor concluded his speech with the following words. Although he looked as restrained as he did at the beginning, his words spoke with particular rhetorical force: "The defendants in the dock are brutal perpetrators of terror, who have written the darkest pages of human history. Death was their instrument and life was their plaything. If these men escape punishment, law and order would lose all meaning and people would have to live in fear".

AFTERWORD

‘Solidarity With Criminals, Not Victims’

The most shocking pages of the book about Ben Ferencz's unprecedented merits and legal triumph are devoted, astonishingly enough, not to the detailed accounts of the crimes of the Einsatzgruppen. The hardest part is to read about how it all ended. No, not at the way the prosecutor demanded. And not even the way the judges decided.

None of the defendants pleaded guilty. All insisted that they were simply good soldiers and carried out their orders.

On 10 April 1947, Ben Ferencz saw SS Gruppenführer Otto Ohlendorf first hear the death sentence - execution by hanging - with a nonchalant face. Showing no reaction, Ohlendorf took off his headphones, nodded, returned to the lift, the door closed behind him, “and it seemed to Ben as if the man was descending to hell”.

“In total, the court handed down fourteen death sentences – more than in any of the subsequent Nuremberg Trials and more than in the trial of major war criminals at the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, which handed down twelve death sentences”. Two were sentenced to life imprisonment. Three were sentenced to twenty years' imprisonment, two to ten years. One earned credit for time served during his pre-trial detention.

The presiding judge, Musmanno had, as he admitted, a "sensitive soul" - and resorted to a ruse: to avoid showing weakness, he read the text from a sheet and kept his reading glasses on, glancing towards the convicts so that their faces would remain "vague and indistinguishable".

It was hard on Ben too: "Every time Musmanno slowly and harshly proclaimed ‘death by hanging’”, Ben felt as if he had been hit on the head with a hammer. “I was afraid my skull would burst open”, he later wrote. Never in his life had he had such a headache. Usually, when a trial was over, the chief prosecutor would throw a small party. To not break with tradition, Ben invited the whole team to his house. But in the evening, he was in no mood to celebrate and went straight to bed. The chief prosecutor, who won the trial and did so confidently, left his party.

The death penalty did not seem too harsh to Ben: “These unrepentant mass murderers deserved it”. On the contrary, he feared that the scale of the crimes might seem "trivial" if the execution of a handful of criminals allowed the matter to be considered settled or even forgotten. “We owe it to the victims to make their deaths more meaningful”, Ben reflected. If their suffering could be exposed and the law could be shown to be unforgiving of such cruelty, only then could the call "Never again!" become a reality. What happened could not be undone, but it was necessary to try to prevent such things from happening again in the future.

After the judge’s announcement, he did something he had not allowed himself to do during the trial: the chief prosecutor visited the main defendant, Otto Ohlendorf, in his cell - and was horrified to see that he had understood nothing, learned nothing, and regretted nothing.

The prisoners were transferred to the Landsberg war criminal prison - Hitler had once served time there, at Hindenburgring 12, after the failed coup on 9 November 1923, and there he wrote the first volume of “Mein Kampf”, formulating the essence of National Socialist ideology, which Ohlendorf and his colleagues then put into practice.

Hitler was released on parole on 20 December 1924. Now, to Ferencz's horror, a similarly peaceful solution was demanded by society for the bloodiest of criminals. The Nuremberg Trials were received very negatively by many Germans, and "victorious justice" was widely criticised. And now the public was seriously condemning the death sentences of the worst mass murderers. Lawyers, journalists, and politicians unanimously protested and called for mercy, carefully avoiding the phrase "war crimes". Prominent members of the church were at the forefront of the defence. Bishops published articles in newspapers with headlines such as "Criminal or Martyr?" - questioning the legitimacy of Ohlendorf's trial, writing to President Truman for a petition of mercy. The tirelessly active Christian social activist Elisabeth von Isenburg, known as the "mother of the Landsbergers", asked Pope Pius XII in a letter on 4 November 1950 to defend "her" prisoners: “I know everyone involved personally. Those who have looked into the souls of these people can no longer speak of guilt or crime”. The Pope promised that Rome would do everything in its power to save the lives of the Landsbergers.

The evangelical pastor of the prison, Karl Hermann, justified his request for the release of Waldemar von Radetzky, an officer from Sonderkommando 4a of Einsatzgruppe C, who had been sentenced to twenty years, by saying that in December 1948 he and other inmates had taken part in a Christmas Eve theatre performance in the prison church, and had organised an artistic evening for Christmas 1949. The pastor, therefore, felt that Radetzky, who knew how to “introduce the prisoners to the world of classical German poetry and music”, would “perform at his best in freedom and make a significant contribution to strengthening the forces within our people, who are preparing to build a new life”.

Convicted mass murderers Paul Blobel and Waldemar Klingelhöfer were welcomed back into the church - after their demonstrative apostasy during the time of National Socialism. The prison's pastor claimed that opera singer Klingelhöfer regularly participated in church services and communions, and was happy to devote his singing art “to the service of the church”. Klingelhöfer, whom the pastor described as “an enemy of all injustice” and “a man our nation desperately needs today for the reconstruction and restoration of a society so corrupt”, recently led the Sonderkommando Moscow and reported the killing of one hundred people on 13 September 1941 and 1,885 civilians from 20 August to 28 September. Under oath at the trial, he said that he had personally shot thirty Jews for leaving the ghetto without permission.

The compassionate public became increasingly louder about the perpetrators merely doing their duty and that the sentences imposed on them were blatantly arbitrary. It became commonplace to claim that confessions had been obtained under undue pressure or torture. The testimony of witnesses was considered dubious and insulting. In post-war German society, Ben recalled, there was little sense of injustice for crimes committed under National Socialist rule. In the ten years Ferencz spent in the country after 1945, he never met a single German who expressed regret, no one ever asked for forgiveness. “The broadest spectrum of German society showed solidarity with the perpetrators, not with the victims”.

On 7 January 1951, 3,000 people marched in Landsberg against the American military justice system. The city administration, in cars with loudspeakers, urged residents to take part in the protest. Between 1950-1951, the campaign reached new heights. American High Commissioner for Occupied Germany John McCloy was under pressure from all sides. Even the German leadership intervened. Chancellor Adenauer personally asked McCloy to commute the death sentences that had not yet been carried out to imprisonment, and Federal President Heuss stood up for the convicted criminal Martin Sandberger, the commander of Sonderkommando 1a in Estonia. Two days after the Landsberg demonstration, leading members of the Bundestag met with McCloy in Frankfurt and also addressed Bundestag President Hermann Ehlers (CDU) and Foreign Policy Committee Chairman Carlo Schmid (SPD). According to the press, they stressed “that the executions must finally stop”. McCloy replied that the final fate of the Landsberg prisoners was not determined by political considerations, but solely by compliance with the principles of law. On the same day, the state parliament of Schleswig-Holstein unanimously passed a resolution demanding that the death sentences not be carried out.

Social Democratic leader Kurt Schumacher said that for part of the protesters it was important “not to keep the sentenced alive, but to justify the inhumanity of the Third Reich”.

Ultimately, McCloy gave up. He announced his decision on 31 January 1951. In "a very large number of cases" he reduced the sentences. “Even with the fifteen condemned to death who were still at Landsberg - the most significant figure among the Einsatzgruppen commanders was Oswald Pohl - McCloy did his best to acquit them: “In these cases, I took into account all circumstances that could justify a pardon and answered all questions of doubt in favour of those convicted”. The High Commissioner summed up by stating that he had sought to “put mercy before justice”.

“Of the fifteen death sentences, five remained in force. Ten were overturned by McCloy. Of the thirteen Einsatzgruppen officers who had been sentenced to death by hanging at Nuremberg on the basis of Ben's indictment, he spared nine from the gallows. In only four cases did he retain capital punishment. He upheld the death sentences imposed on Ohlendorf, Naumann, Blobel, and Braune as well as Pohl in the case against the SS Main Economic and Administrative Office. In these cases, the “incomprehensibility of the crimes for which these men are responsible” ruled out any pardon. As “commanding officers of SS Einsatzgruppen or punitive units”, Ohlendorf and his comrades murdered all Jews, Roma, the mentally disabled, and communists who fell into their hands.

McCloy commuted the death sentences of Biberstein, Klingelhöfer, Ott, and Sandberger to life imprisonment by way of clemency. Instead of facing the executioner, Blume, Steimle, Haensch, Seibert, and Schubert were sentenced to terms of imprisonment ranging from ten to twenty-five years. The other sentenced men also benefited from the reductions, some of them substantial. Jost and Nosske, sentenced to life imprisonment at Nuremberg, now had to serve a sentence of ten years, Schulz’s was commuted from twenty to fifteen years in prison. Six's sentence was halved from twenty to ten years. Rühl and Radetzky were allowed to remove their prison clothes and were immediately released from prison. Earlier, McCloy had introduced a system of bonuses for time served. Prisoners had their sentence reduced by five days a month for good behaviour. Now the bonus had been doubled.

But this was not enough for Germany either. The campaign in defence of the convicts flared up with renewed vigour. Between 31 January and 9 March 1951, more than a thousand letters arrived at the High Commissioner's office on the matter. Most of them called for a pardon and further reduction of sentences. More than 600,000 people signed a petition for a general amnesty. During a debate in the Baden-Württemberg Landtag, Heinz Burnelheit, a member of the German People's Party (DVP), called the planned executions "legalised murder". Oswald Pohl published an open letter under the headline "I accuse!" (Ich klage an!), and an anti-American pamphlet published in February 1951 on the occasion of the trial of the SS leadership referred unequivocally to the “German Dreyfus affair”. The cynicism of the situation stemmed from Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a Jew by nationality, being sentenced in France in 1884 to life imprisonment on Devil's Island because of a miscarriage of justice caused by anti-Semitic views, and Emile Zola, with a public letter "I accuse...!" ("J'accuse...!"), addressed to the president of the Republic, obtained a review of the case. The Nazis, murderers of Jews, were now shamelessly comparing themselves to the most famous victim of an anti-Semitic legal system.

Despite the pressure, McCloy upheld the death sentences of the remaining five. "On the evening before the execution, the convicts said goodbye to their wives. According to the report, they appeared calm and resigned to their fate - the same thing the mass murderers at Nuremberg said about their Jewish victims. Blobel and Braune declared that they would die innocent. Ohlendorf seemed aloof. Naumann's last words were: “The time will come when we shall see whether my execution was justified or not”. The four leaders of the Einsatzgruppen were hanged on 7 June 1951, between midnight and 1:43 a.m. in the courtyard of the Landsberg Prison. The order was determined alphabetically. Blobel went first, then Braune, Naumann, and finally Ohlendorf. The bodies were buried in unmarked graves at the Spöttinger Cemetery next to the prison, to avoid a martyr cult. A few days later Ohlendorf’s remains were moved to a family grave in the Lower Saxony town of Celle. So many people gathered at the cemetery that there was not enough room for everyone, and some waited outside the cemetery grounds. Ben saved an article cut out of a newspaper from 16 June 1951, with a large photograph. The text read: “The hands of the 1,300 people who had gathered in and around the cemetery in Celle rose in a ‘Hitler Salute’ as the coffin containing the remains of the former SS Gruppenführer Ohlendorf, the last of the seven war criminals executed at Landsberg, was lowered into the grave”.

The American High Commissioner McCloy gave up, then his successor James Conant continued this policy of appeasement - criminals were getting out of prison earlier and faster, no one remembered the old terms and severity of punishment. By the mid-50s almost everyone was out. The last convicts at Nuremberg were released from Landsberg Prison on 9 May 1958.

They returned to respectable civil service. “Steimle taught at a Protestant boys' school in Württemberg. Blume offered his legal expertise in a real estate company. Sandberger worked as a lawyer in a high-tech company. Between 1971 and 1972 the prosecutor's office at Stuttgart's Land Court investigated Sandberger ‘for crimes of National Socialism’. The prosecutors asked Ben for help and he provided references to some important documents that supported the facts. However, the proceedings were soon dropped on the grounds that Sandberger had previously been convicted at Nuremberg. Six used his connections with other former members of the NSDAP and after his release worked with former SS officer Werner Best, deputy of SS-Obergruppenführer Reinhard Heydrich and the Reich’s Plenipotentiary in occupied Denmark, on a general amnesty for war criminals”.

“The industrialist Friedrich Flick, whom Six had met in Landsberg, made his way into the management of the Leske Verlag publishing house in Darmstadt in 1953. Flick later worked as an advertising manager at the tractor manufacturer Porsche-Diesel Motorenbau in Manzell on the shores of Lake Constance and as an independent management consultant, teaching marketing at an academy for business leaders. In the early 1970s, Hermann Giesler, one of Hitler's favourite architects, built Six a house in South Tyrol. The former SS brigade commander stuck to National Socialist ideas for the rest of his life. In the foreword to his book ‘Another Hitler’ (1977), he described his time at Landsberg, together with other convicted war criminals, as ‘years of fortitude, confirmation of once found epiphanies and the correctness of revolutionary goals’”.

“It was horrifying: the murderers from Himmler's punitive units lived without remorse or the slightest sense of guilt, as recognised members of democratic German post-war society. Already by 1951, when the first Einsatzgruppen criminals were released, Ben could meet them at any time in a restaurant or on a tram: 'I often thought about it. I travelled a lot, including by train, and always looked in the compartment first to see who was sitting in it’”.

Ben received constant death threats. But most frightening to him was, in fact, the collapse of his life's work: “To release mass murderers was a disgrace. It seemed to me that some of the decisions showed more mercy than justice”, he said, referring sardonically to McCloy's credo of “putting mercy over justice”.