The editorial team at the “Nuremberg: Casus Pacis” project and the Eksmo publishing house continue their series of excerpts from Swiss historian Philipp Gut’s book ‘Jahrhundertzeuge Ben Ferencz’ (Witness to the Century Ben Ferencz).

The legendary lawyer, the youngest prosecutor at the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal, initiated and conducted the largest mass murder case – the Einsatzgruppen Trial. To find out how he obtained the evidence – the scrupulous reports on the extermination of "Untermenschen" (the word the Germans used to describe those whom they considered inferior) in the occupied territories of the USSR, compiled by the Nazis themselves – read here (link to part 1).

Ben Ferencz analysed the documents in his possession until the spring of 1947, compiled a list of killers and used a mechanical calculator to determine the staggering number of victims. He then reported his sensational work to his superior –Telford Taylor, Chief US Prosecutor at Nuremberg – and demanded a new trial.

At first, his demands were met with a certain lack of enthusiasm: Taylor complained that there was no money left in the Pentagon for new trials, and support for the tribunal in Germany was weakening before their eyes. Nevertheless, Ferencz was determined and was prepared to take on the job in addition to his current duties.

And so he became chief prosecutor in the biggest murder trial ever held. He was also the youngest prosecutor and this was the first case in his career, at the age of 27.

He initially intended to bring charges against leading SS figures from the security, intelligence, and police branches but had too few resources, so the focus of the trial shifted specifically to criminals from the Einsatzgruppen or "Task Forces" - the Nazis' paramilitary death squads who were responsible for so many of the mass killings of civilians during the Second World War.

CHAPTER 5. THE PROCESS

Selecting the Defendants

The first thing Ferencz had to do to prepare for the trial was to secure the folders containing the "reports on the events". The documents were sealed in a bag marked "US Post" and taken to the Berlin Document Centre (BDC) in the district of Zehlendorf. The BDC was located in an underground room that had served as a listening station for Göring's Reich Air Ministry during the war, and now stored documents from the National Socialist era collected for the Nuremberg Trials. In addition to SS personnel files, correspondence and other materials, the centre's collection contained NSDAP membership cards.

The documentary evidence then had to be compared with the testimony of the criminals who were alive and in custody. After all, they were the only ones who could be prosecuted. But who was Ferencz supposed to charge? In total, some 3,000 members of the Einsatzgruppen murdered defenceless men, women, and children almost every day - it was impossible to bring all the culprits to trial.

Nevertheless, Ben and his team managed to put together an almost complete list of Einsatzgruppen members. Copies of these documents were sent to all Allied prisoner-of-war camps, requesting that they report suspects and transfer them to Nuremberg. Some of the SS leaders were already there; they were apprehended first.

The number of mass murderers who could be charged depended, in addition to limited financial resources, on the equipment in the Nuremberg Palace of Justice’s courtroom. None of the 12 trials could have more than 24 defendants for the simple reason that there were only 24 seats in the dock. Inevitably many fish slipped through the net - including some big ones, Ferencz says. The organisers of the Nuremberg Trials originally had no greater object than to prosecute a small group of the major Nazi criminals.

"Was it fair?" Ferencz wonders and then answers himself: "I chose 24 suspects to indict. I could prove the guilt of 3,000 criminals. Where was the justice? It wasn't justice. It was a selection, an example, to show the world what happened and to bring some of the guilty to justice". Unfortunately, justice is not always perfect.

On top of these restrictions, he identified two criteria for selecting defendants: precedence and education. Ordinary, poorly educated men were more likely to get off because responsibility starts at the top. Therefore, the men he brought to trial were mostly from the highest ranks of the SS. They had grown up in prosperous families, received some proper education, and made a rapid rise in the National Socialist German Reich through personal ability and unconditional loyalty to the government.

The main defendant and at the same time "the most interesting and complex personality" among the defendants was Otto Ohlendorf, SS-Gruppenführer and commanding officer of Einsatzgruppe D.

He was born in 1907 and grew up at an estate near Hildesheim. His father was a national liberal of the old school and an active member of the German People's Party. As a young man, Ohlendorf became interested in the organisation and management of his father's estate. He studied law and political science at the universities of Leipzig and Göttingen, taught at the Kiel Institute for the World Economy and the College of Commerce in Berlin.

Ohlendorf spent one year in Fascist Italy "studying the Fascist system and the Fascist philosophy of international law", as he stated in his testimony before a military tribunal. He joined the NSDAP in 1925 and the SS in 1927. Ohlendorf career in the security bloc of the NSDAP apparatus proved meteoric and he took part in organising Himmler's Security Service (SD) and became an economic adviser there. In 1939, he was appointed head of the Amt III (SD-Inland) of the Reich Security Main Office (the newly formed RSHA involved in SS counter-espionage and information-gathering service).

After a role in the Soviet Union as commander of Einsatzgruppe D, which lasted from June 1941 to June 1942, Walther Funk appointed Ohlendorf deputy undersecretary of state and then deputy director-general in the Reich Ministry of Economic Affairs. In May 1945, when the Nazi state was about to end, Ohlendorf was the de facto Minister of Economics in the "Flensburg Government" of Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz. He was arrested shortly afterwards.

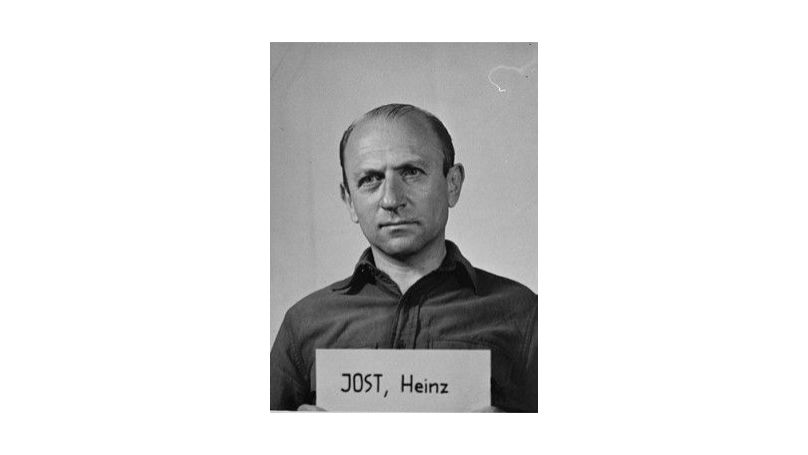

The prosecution team succeeded in bringing not only Ohlendorf to trial but also three other Einsatzgruppen commanding officers. Heinz Jost, SS-Brigadeführer, Commander-in-Chief of Security Police and SD, commanded the Einsatzgruppe A.

He was also a lawyer and a member of the SS leadership.

In 1933, Jost was appointed Director of Police in the city of Worms and then police director of Giessen. In 1934, he continued his career in Himmler's empire, quickly rising to a senior position in the SD Main Office and then in the RSHA. In August 1939, Jost was commissioned by RSHA chief Reinhard Heydrich to provide the Polish uniforms needed to stage a false flag attack on a radio station in Gleiwitz. This setup was used by Hitler as a pretext for ordering the invasion of Poland.

In addition to commanding Einsatzgruppe A, Jost assumed command of the Security Police and SD in Ostland in Riga, Latvia from March to September 1942.

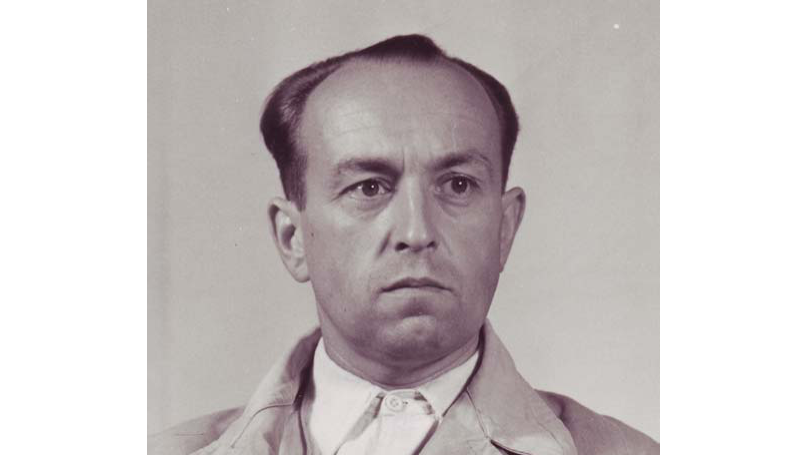

The third in the group was Erich Naumann, commanding officer of Einsatzgruppe B.

He was originally a commissioner within the SA, responsible for matters relating to higher education (despite having left school at the age of 16). In 1935, he enlisted in the SS and worked in their security service. At the head office of the SD in Berlin, he headed the department under Jost. Naumann later served as an inspector of the security police and the SD.

At the time of the German attack on Poland, he had already given orders as a commanding officer of the Einsatzgruppe during Operation Tannenberg to "fight against all anti-imperial and anti-German elements in the rear of the fighting forces" and to destroy Polish intellectuals.

By the summer of 1941 he was at the headquarters of Einsatzgruppe B, over which he assumed command in November. From September 1943 to July 1944, Naumann headed the Security Police and the SD in the Netherlands.

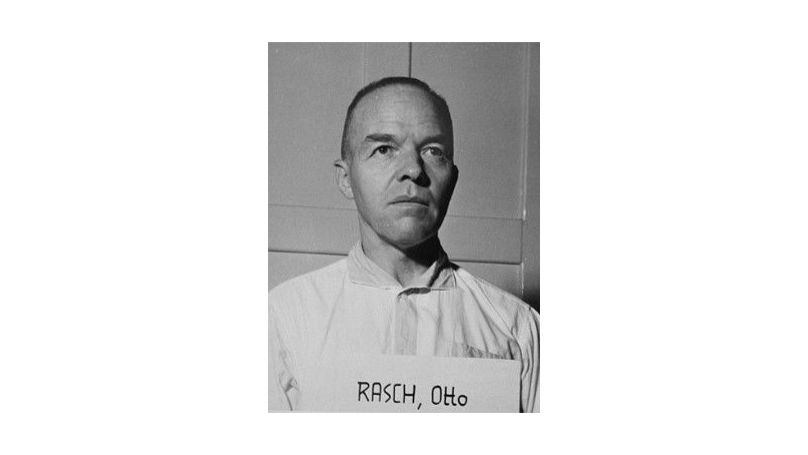

The fourth SS commander Ferencz sent to the dock was Otto Rasch, commanding officer of Einsatzgruppe C.

Rasch was a brilliant scholar with two doctorates in political economy and law. He worked as a lawyer in Leipzig and advised various companies. After Hitler's rise to power, he became Mayor of Radeberg and then Lord Mayor of Wittenberg. Starting in 1939, he worked for the Gestapo and the security services in leadership positions in Frankfurt am Main, Linz, Prague, and Königsberg; in East Prussia, he was in charge of the concentration and extermination camp Soldau.

On 31 August 1939, he led the SS attack on the woodsman's cottage in Pinczyn, a theatrical attack, such as the one on the radio station in Gleiwitz, which was dressed up to look as though it was an invasion by the Polish Army. Rasch commanded Einsatzgruppe C from when it was founded until October 1941, when he ordered the mass execution at Babyn Yar. By 20 October his units had reported 80,000 "specially treated", meaning "killed", people.

Franz Six seemed like an intellectual compared with the rest of the defendants.

The future leader of Sonderkommando 7c (Vorkommando Moscow), a unit of Einsatzgruppe B, had a blazing academic career. At the age of 25 he received a doctorate in political propaganda for National Socialism (1934); at 28, he was a professor of journalism at the University of Königsberg; at 30, he was chairman of the Department of International Studies and director of the Institute for International Studies in Berlin. Six acted as head of the press department at the SD Headquarters and as head of the RSHA.

Under Himmler, he was responsible for "worldview research issues". He supported the Holocaust of European Jews, mostly by developing propaganda materials, but with logistical solutions. Together with Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller – according to Auschwitz Commandant Rudolf Höss, "the cold-blooded executor" of all Himmler's orders – Six worked on "state police training" for the attack on Poland. In June 1941, Heydrich entrusted him with the command of the Vorkommando Moscow (advance team "Moscow").

In September 1942, Six was transferred to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs under Joachim von Ribbentrop. There he headed the cultural-political department dedicated to propaganda, the subject of his dissertation.

There were many lawyers among the defendants. As well as the three individuals already mentioned, Walter Blume, Martin Sandberger, Werner Braune, Walter Haensch, Gustav Nosske, Erwin Schulz (did not complete his degree), and Eduard Strauch had received legal training. Their expertise in this area did not prevent them from committing the most egregious violations of the law. In July 1943, Generalkommissar for Weissruthenien (Belarus) Wilhelm Kube praised the "extremely capable [...] Doctor of Law Strauch", saying it was thanks to him that "55,000 Jews were eliminated in the past 10 weeks".

It was not only lawyers and economists who mastered the craft of murder. Waldemar Klingelhöfer was a musically gifted mass murderer – he had been an opera singer before his career as an SS officer. Gymnasium teacher Eugen Steimle came from a very devout family; Ernst Biberstein served as a Protestant theologian and pastor.

Paul Blobel, notorious for his brutality even in this gallery of mass murderers, worked as a stonemason and carpenter before pursuing a career in the security services. Adolf Ott was active in the German Labour Front before joining the SS, Waldemar von Radetzky trained at a transport and shipping company, Felix Rühl was a court clerk, Heinz Schubert studied at the Higher School of Commerce and then worked in a law office. Matthias Graf was a merchant and Emil Haussmann taught at a primary school.

They were all chosen by the SS leadership because they were deemed fit to do the dirtiest work in the extermination campaign in the East.