Seventy-five years ago, the most important tribunal in history completed its work culminating in the conviction of the main Nazi criminals. Here, we recount the events which took place in the Nuremberg Palace of Justice on 1 October 1946.

"Tense Depression in the Jail"

On 31 August, the court had heard the last of the interrogations and was considering its verdict. According to prison psychologist Gustave Gilbert, who worked at Nuremberg: "As the defendants awaited the verdict, there was a tense depression in the jail, in spite of the relaxation of prison rules, allowing visits from wives and among themselves".

"Goering acknowledged defeat on the psychological front. Ribbentrop was almost pathetic in his confusing repetition of the old rationalisations and lies, and in the pale fear of death that crept into his haggard face. [He even suggested to Gilbert that he could make a great historical gesture by interceding on behalf of the defendants]. Keitel was depressed and declined to see his wife. Sauckel, Rosenberg, Fritzsche, Funk paced their cells or lay on their cots staring at the ceiling. Raeder repeated that he had no illusions about getting off with less than the death sentence. Schacht was the only confident one".

The Tower of Babel

The verdict was read on 30 September. Arkady Poltorak, secretary of the Soviet delegation, recalled: "On that day I arrived very early at the Palace of Justice and already at the entrance of the building I felt that the atmosphere was very unusual. There were a lot more police cars in the driveway. There were more guards. Suitcases were searched by officers; permits were carefully compared with passports. The procedure was compulsory for everyone, whether members of the press, court staff, lawyers or visitors".

Poltorak continues: "There were many people who attended the trial only in the first weeks. Now they were back. They came back again. The courtroom witnessed the confusion of the Tower of Babel, where people from all over the world were gathered".

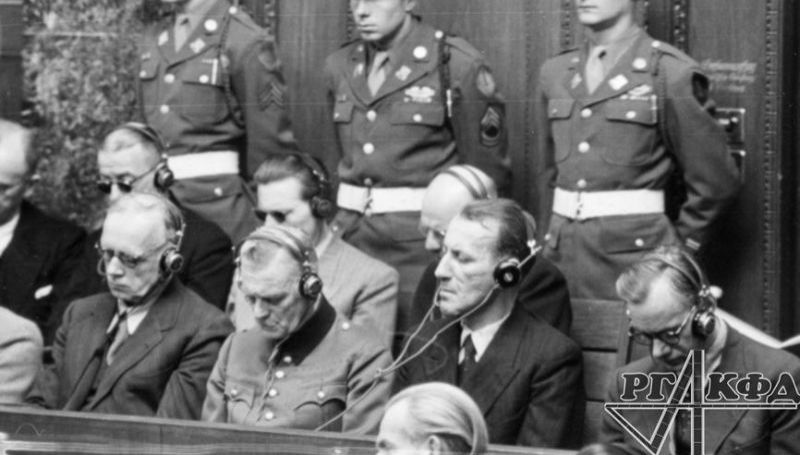

Alexander Zvyagintsev, who has researched the Nuremberg Process and wrote "The Nuremberg Trials", describes: "To accommodate more people, all the extra tables were removed from the room and replaced with chairs. Tickets were printed in two colours to allow a person to attend only one of the two most important sessions, and on the last day when individual sentences were pronounced, the tickets for back seats were valid for only half a day. Around 9:30 am, the defence counsels took up their seats, just as stenographers and interpreters. There were scores of technicians in radio cabins, and the gallery was overcrowded. One by one, the defendants were brought into the courtroom. They looked 'exceptionally tense' and behaved as if they did not know each other".

"Then the judges came out of the jury room and Geoffrey Lawrence (later Lord Oaksey), president of the tribunal, held a large folder which contained the verdict".

The judges worked on the verdict for several months, discussing it paragraph by paragraph, deciding the fate of each defendant. War crimes and crimes against humanity were the least discussed. The conspiracy charge, on the other hand, was a subject of heated debate, and the section on crimes against peace had been drawn up for two months. Rosenberg, Frick and Seyß-Inquart had a chance to avoid the death penalty, whereas Funk and von Schirach could easily find themselves swinging from a noose.

Unlike the verdict itself, the charges under which the defendants were to be found guilty, or their prison term, were open to heated discussion. The Soviet judges, who held a harder line during the tribunal, were now noticeably more flexible. They were ready to accept a compromise but not an acquittal, which later caused their open protest.

Poltorak says: "Hour by hour, the defence counsels [and their deputies] took turns reading this historical document. After a whole day of reading, the full verdict has not been pronounced".

Celebrated lawyer and historian, Philippe Sands, explains: "The first day was devoted solely to legal reasoning and a general review of the facts, which the judges divided into sections. Complex interlocks of historical events and human actions were simplified to a narrative that clearly described the Nazi takeover of power, acts of aggression in Europe, criminal warfare. It took 453 public sessions to review those 12 years of chaos, violence and murder. 94 witnesses were heard, 33 from the prosecution and 61 from the defence".

The verdict established for the first time in international law the concept of crimes against humanity. Those gathered in the courtroom listened in silence to descriptions of killings, looting, forced labour, persecution - all of which were henceforth considered international crimes.

The tribunal used a formula announced by British chief prosecutor, Sir Hartley Shawcross: international crimes "are committed by people, not by abstract organisations". International justice can be dispensed only if criminals are punished, and every human being has obligations under international law "that go beyond obedience to national laws imposed by a particular State".

Most Sensational Morning

The next morning, the judges proceeded to the defendants’ individual responsibility. Some of the defendants listened to the verdict very attentively, some restlessly moved back and forth, some acted as if the ongoing process had nothing to do with them.

The declaration of intent read that Schacht, Papen and Fritzsche had been acquitted by the International Military Tribunal. "As the acquittal was read, a buzz of conversation could be heard around the room. This reaction seemed to be as diverse as those present in the courtroom themselves", Poltorak says.

According to Poltorak, he was not surprised by the verdict.

"The positions of the judges regarding Schacht, Papen and Fritzsche were revealed during closed sessions of the tribunal", he explained. "During these meetings, the Soviet defence counsel had to argue the statements made by the western defence counsels, who clearly expressed their opinion, which eventually resulted in the acquittal of these three".

When the court ordered the Commandant to release the three defendants, Fritzsche and von Papen said farewell to other defendants and only Schacht passed by Göring without even looking at him. The other defendants remained in the courtroom, as their verdicts had not yet been read.

Poltorak describes: "The Palace of Justice was livelier than ever. It was the most sensational morning, and the world's press rushed to report this sensation to the world. There was a rumour that there was an improvised press conference taking place in one of the halls of the Palace with the 'heroes' who had been acquitted. I went there. The room was filled with correspondents from all over the world, primarily American and British ones. Interviewees responded to a series of questions with smug looks. They lied just as they did from the dock". Soviet journalists did not visit this "press conference".

Dead Silence

After the lunch break, at 2.50 pm, the tribunal began the final of 407 sessions.

Poltorak remembers: "The atmosphere had changed dramatically. Spotlights, which were used for presenting films and photographs were removed from the courtroom [photography was not allowed at the last meeting]. There was only the blue light of the neon tubes lighting the walls and faces of prosecutors, defenders, secretariat staff and numerous visitors".

"The dock was empty. There was dead silence in the courtroom. Whenever anyone coughed from time to time, it sounded like an unexpected artillery volley. Everyone was waiting for the tribunal to pronounce its judgement on each defendant. The eyes were fixed on two doors – the one from which the defence counsels were to enter and the other one behind which were the defendants who were to file in one by one".

"Here come the judges. After Lawrence nodded, everyone sat down".

The judicial disposition of the verdict, which contained penalties for the defendants, was proclaimed by the president alone. The participants in the trial were brought individually into the room to hear the verdict read, and then were taken out - and this happened 18 times in succession. Another defendant, Martin Bormann, was tried in absentia. In case of a heart attack, fainting or hysteria, there was a doctor and nurse in the courtroom as well as two soldiers with a stretcher and a straitjacket.

Philippe Sands says: "For the first time of this year-long trial, the 18 defendants found guilty and awaiting only a specific sentence were not treated as a single group, but as individuals. They weren't brought into the courtroom all together - each one waited for his turn outside, near the elevator. Each entered the courtroom, listened to the verdict, and then went out".

The chief prosecutors demanded that all defendants be sentenced to death in their closing speeches [the exception being United States attorney Robert Jackson, who did not propose a specific punishment, but simply said that "finding these people not guilty would mean that there was no war, no murder, no crime"]. It was easy to predict that the tribunal would not be so harsh. Nevertheless, 12 of the 22 sentences implied the death penalty.

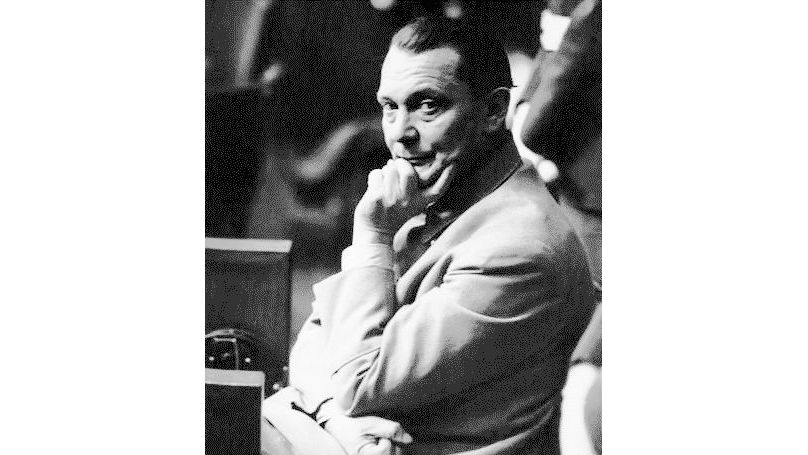

Each of the convicts reacted in his own way: according to Poltorak, Göring "fixed the judges with one final look of pure venomous hatred" and silently left the courtroom; the grey-haired and frightened-looking Ribbentrop hardly turned to the exit; Keitel stood straight "like a candle" as if he was impervious; Rosenberg lost his temper; Frank had his arms open; Streicher tilted his head forward while awaiting the sentence; Jodl "hissed viciously".

Hess, who was sentenced to life imprisonment, "looked like silly", and Funk who seemed as though he was ready for capital punishment, was "clearly confused" and almost cried when he learnt he was going to live.

Soviet lawyer and an assistant prosecutor at the trial, Mark Raginsky, said: "I followed the conduct of Rosenberg, Keitel, Kaltenbrunner, Frick, Frank, Jodl, Sauckel, Streicher and Seyß-Inquart, who were sentenced to death, very closely. With the exception of Seyß-Inquart, they were all responsible for the murder of millions of people and could not hide their fear. The guards had to support Ribbentrop, Rosenberg, and Jodl from both sides, as they could not stand on their own".

Poltorak reports: "The trial is over. The judges are leaving the courtroom. There is a terrible noise in the corridors of the Palace of Justice. The crowd of journalists speak every known language and they have rushed to the telegraph and telephones. Almost knocking each other to the floor, they rush to file to their newspapers and agencies the breaking news about the tribunal which lasted almost a year: 12 defendants - Göring, Ribbentrop, Keitel, Rosenberg, Kaltenbrunner, Frick, Frank, Streicher, Sauckel, Jodl, Seyß-Inquart and Martin Bormann in absentia - sentenced to death by hanging; three of the defendants - Hess, Funk and Reder - to life imprisonment; two - Schirach and Speer - to 20 years in prison; Neurath - to 15 years; and Dönitz - to 10 years".

It is a sign of how greatly the convicts were held in contempt that the tribunal chose hanging as their means of execution. From time immemorial, this was considered a death for those who had been dishonoured: in ancient times military folk were beheaded and, after the invention of firearms, shot.

In addition to individual sentencing, the tribunal ruled on the case of Nazi organisations. The leadership of the NSDAP, the SS, the Security Police (SD) and the Gestapo were recognised as criminal organisations and all their members were subject to individual criminal responsibility for specific crimes. The Imperial Cabinet, the General Staff, the High Command of the Wehrmacht and the SA were acquitted by the tribunal. So far as the trial was concerned, neither the General Staff nor the High Command of the Wehrmacht was an organisation or group in the legal sense, and the SA was a disparate entity. However, the tribunal stressed that there was no doubt about the guilt of the Nazi Germany generals.

After reading the verdict, Lawrence noted that Soviet defence counsel, Iona Nikitchenko, had expressed a dissenting opinion, which immediately set the press corps abuzz with excitement. The Soviet representative disagreed with the acquittal of Schacht, von Papen, and Fritzsche and he maintained that Rudolf Hess, who was sentenced to life imprisonment, deserved the death penalty. He also protested against the fact that the Imperial Cabinet of Ministers, the General Staff, and the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht had not been deemed criminal organisations. However, he had no problem with any of the other verdicts of the trial.

Raginsky recalled: "Many of my fellow lawyers, members of the press, came to me and said, 'We agree with your defence counsel, that they are all guilty, and they should all have been severely convicted'".

Although the text of the dissenting opinion was agreed on, or - as some historians believe - even written in Moscow, it was not designed as propaganda, and the precision of the legal language is still impressive.

"From the dissenting opinion of the Soviet Member of the International Military Tribunal, Major-General Jurisprudence IT Nikitchenko:

'It is thus indisputably established that:

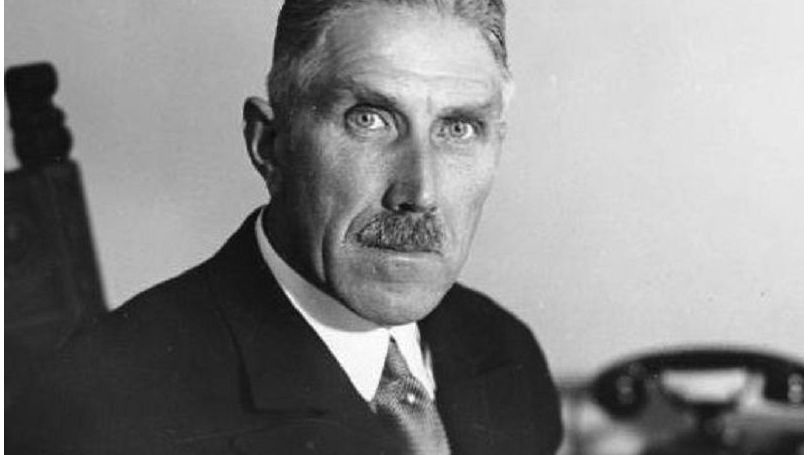

(1) Schacht actively assisted in the seizure of power by the Nazis;

(2) During a period of 12 years Schacht closely collaborated with Hitler:

(3) Schacht provided the economic and financial basis for the creation of the Hitlerite military machine;

(4) Schacht prepared Germany's economy for the waging of aggressive wars;

(5) Schacht participated in the persecution of Jews and in the plunder of territories occupied by the Germans.

Therefore, Schacht's leading part in the preparation and execution of the common criminal plan is proved.

The decision to acquit Schacht is thus in obvious contradiction with the evidence in which is in the tribunal's possession".

"Americans Won't Hang a Banker"

Public reaction to the verdict was mixed. The US chief prosecutor, Robert Jackson, approved the final decision but disagreed with the acquittal of Papen and Schacht. The Austrian Minister of Justice demanded Papen’s extradition to Vienna.

The Belgian press strongly condemned the acquittals, and the Dutch 'De Volkskrant' reported in its headline that the verdict 'was not final". 'The Guardian' reported "The Nazi leaders will die on 16 October", and 'The Evening News' urged "We must hang them all".

The Soviet press expressed general satisfaction with the process and supported Iona Nikitchenko's dissent. The main Moscow newspapers had similar headlines: 'Pravda' described the verdict as "the historical Judgement", and 'Izvestia' named it "The conviction of Hitlerism".

It might seem strange to today's readers that 'The Guardian', a well-known organ of the liberal left, held such hardline views but it wrote: "When 12 people are to be hanged, it seems strange that Schacht and von Papen escaped even imprisonment and were acquitted. Fritzsche (...) hardly deserved a place in the dock alongside the greatest villains, but Papen will always remain a sinister figure in the history of Germany (...) Schacht (...) supported the mind that created the material basis of the 'conspiracy'. Was this astute man not aware of the purpose that his talents served? It is noteworthy that the Soviet dissenting opinion took those points into account and that the chief United States prosecutor Robert Jackson also expressed regret over the acquittal of Schacht and Papen".

Many prosecutors were concerned by the acquittals: for instance, the case of the Schacht confirmed the widely held view that "Americans won't hang a banker". Former US Secretary of State Henry Stimson, one of the main initiators of the trial, praised the tribunal's achievements, but was somewhat sceptical of the verdict, regretting the narrow definition of the term "conspiracy".

However, the lawyers appreciated the fact that the final decision did not contain the principle of collective responsibility.

The acquittals were also unpopular with many Germans, and their dissatisfaction was exploited by the Soviets. According to Poltorak's memoirs, in Leipzig alone "100,000 people demonstrated", waving banners with slogans "Death to war criminals!", "We want a long-lasting peace!", "Popular trial of Papen, Schacht and Fritzsche!", "We want peace!". Similar protests were held in Dresden, Halle and Chemnitz.

Death!

But for a vivid description of how the convicts reacted to their sentence, it is to the Jewish-American psychiatrist Gustave Gilbert that we once again turn.

"'Death!' Göring said as he dropped on the cot and reached for a book", Gilbert recounted. "His hands were trembling in spite of his attempt to appear nonchalant. His eyes were moist and he was panting, fighting back an emotional breakdown. He asked me in an unsteady voice to leave him alone for a while".

"Hess strutted in, laughing nervously, and said that he had not even been listening, so he did not know what the sentence was - and, what was more, he didn't care. As the guard unlocked his handcuffs, he asked why he had been handcuffed and Goering had not".

"Ribbentrop wandered in, aghast, and started to walk around the cell in a daze, whispering, 'Death!—Death! Now I won't be able to write my beautiful memoirs. So much hatred!'"

"Sauckel was perspiring and trembling all over when I entered his cell. Jodl marched to his cell, rigid and upright, avoiding my glance. And then he said 'Death - by hanging! That, at least, I did not deserve. The death part - all right, somebody has to stand for the responsibility. But that…'".

"Seyss-Inquart smiled, but the crack in his voice belied the casualness of his words. Frick shrugged, callous to the end. 'Hanging. I didn't expect anything different'".

"Speer laughed nervously. 'Twenty years. Well, that's fair enough. They couldn't have given me a lighter sentence, considering the facts'. Von Neurath stammered, 'Fifteen years'".

"Those sentenced to death remained in their cells and those who received prison sentences were transferred to new cells".

Oranges

The feelings among the three defendants who had been acquitted varied widely. As Gilbert tells us: "Fritzsche was so unnerved and overcome, he seemed to lose his balance and almost fell over as though he were dizzy".

"Von Papen was elated and quite obviously surprised. 'I had hoped for it, but did not really expect it'. Then, with a gesture of compassion, he took an orange he had saved from lunch out of his pocket, and asked me to give it to von Neurath". Fritzsche asked Gilbert to give his orange to von Schirach. Schacht ate his own orange.

However, the three acquitted defendants found it difficult to enjoy their freedom. "No sooner had their acquittal been announced than the German civil administration declared its intention to arrest them and try them for the betrayal of the German people. A cordon of Nuremberg police was thrown around the Palace of Justice to catch them as they came out", Gilbert said.

For three days and nights, they remained in jail at their own request, fearing to face their own people. Von Papen declared himself a hunted animal, Fritzsche asked Gilbert for a pistol, saying that he could not stand this torture any longer.

Finally, in the middle of the night, two of the three decided to leave the prison. According to Fritzsche's memoirs, which Poltorak refers to, two American trucks entered the prison yard. One was for Schacht, and the other for Fritzsche.

Papen didn't dare to leave the prison until mid-October, having corresponded with the leadership of the western occupation zones in Germany.

But soon all of them were arrested and tried again – this time by a German trial.

We are grateful to Sergey Miroshnichenko, a lawyer and international law scholar, for his assistance in preparing the material.

Sources:

Arkady Poltorak. Nuremberg Epilogue

Gustave Mark Gilbert. The Nuremberg Diary

Philippe Sands East West Street: On the Origins of 'Genocide' and 'Crimes Against Humanity'.

Alexander Zvyagintsev. The Nuremberg tocsin. Reporting from the past, addressing the future. Moscow: OLMA Media Group, 2006

Mark Raginsky. Nuremberg: the Trial of History. Memoirs of a participant of the Nuremberg Tribunal

Tusa A., Tusa J. The Nuremberg Trial

Weinke A. Die Nürnberger Prozesse

Hirsch, Francine. Soviet judgment at Nuremberg: a new history of the international military tribunal after World War II

Priemel K. C. The Betrayal: The Nuremberg Trials and German Divergence

Editorial: the sentences // The Guardian, 2 October 1946

By Daniil Sidorov