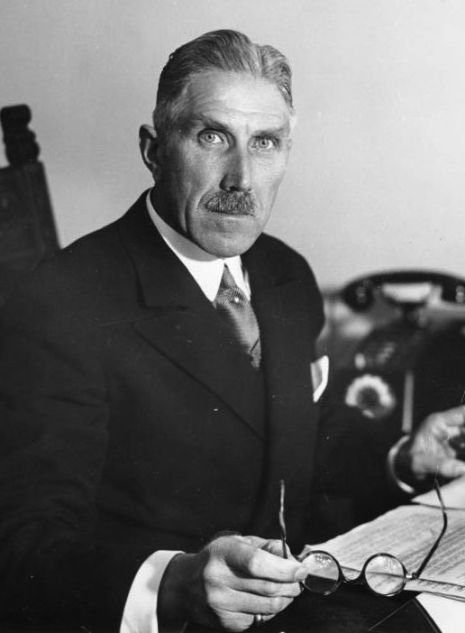

On 18 and 19 June, the Nuremberg Tribunal began the cross-examination of Franz von Papen, former chancellor, vice-chancellor, and ambassador of Nazi Germany to Austria and Turkey. In all his 67 years, this defendant at the Nuremberg Trials had managed to betray everything he believed in and was proud of.

The honour of an aristocrat, the dignity of an officer, the patriotism of a chancellor, the principles of a diplomat. He was one of those who allowed Hitler’s rise to power, and those who personified Nazi Germany across the globe. Having honestly earned military honours in World War I, in World War II he displayed unprecedented cowardice and weakness. The noblest of the Nuremberg defendants was even despised by his fellow prisoners in the dock.

Many years later he of course wrote his memoirs - a temptation that almost none of the survivors of the Nuremberg Tribunal avoided. But perhaps no one in this field demonstrated such imagination and particularly the art of flirtatious self-justification.

"My own life seems to a very large extent to have been written for me (…). I have been represented as a master spy and mystery man, a political intriguer and plotter, and a two-faced diplomat. I have been called a stupid muddler and a naïve gentleman rider, incapable of grasping the true implications of a political situation. I am written off as a black-hearted reactionary who deliberately plotted Hitler's rise to power and supported the Nazi regime with all the influence at his command. I have been arraigned as the architect of the rape of Austria, and the exponent of Hitler’s aggressive policy when I was German ambassador in Turkey during the second world war. (…) I realise what a splendid subject I must have been for the propaganda machines. I have run the whole gamut, from being chancellor of my country to appearing as a war criminal in the Nuremberg dock on a capital charge. I served my country for almost fifty years and have spent half the time since the second world war in gaol. I stand accused as a supporter of Hitler, yet his Gestapo always had me on their liquidation list and assassinated several of my closest collaborators. I spent the better half of my life as a soldier, protected on many battlefields by some benevolent angel, only to escape death by a hair’s breadth at the hands of a hired assassin with a Russian bomb. (…) As a convinced monarchist, I was called upon to serve a republic. By tradition a man of conservative inclinations, I was branded as a lackey of Hitler and a sympathiser with his totalitarian ideas. By upbringing and experience as a supporter of true social reform, I acquired the reputation of being an enemy of the working classes. (…) Seeking only a peaceful solution to the German-Austrian problem – and thereby incurring the bitter hatred of the Austrian Nazis – I stand accused of organising Hitler’s Anschluss. After fighting all my life for a strong position for Germany in Central Europe, I have had to watch half my country engulfed by the despotism of the East. Although an ardent Catholic, I came to be regarded as the servant of one of the most godless governments in modern times. I am under no illusion as to the reputation I enjoy abroad".

In this foreword to his "Memoirs", Franz von Papen demonstrates a masterful craftiness: yes, all the milestones are named, yet none is honestly assessed.

Officer and Gentleman

Franz Joseph Hermann Michael Maria von Papen, Erbsälzer zu Werl und Neuwerk was indeed a true nobleman, a rare bird among the rabble who had reached the heights of power in the Third Reich. "Erbsälzer" was a noble title, tracing its origin back to the patricians of the free city of Werl, with their hereditary right to exploit the nearby salt mines.

His father, Friedrich von Papen-Könningen, was a major landowner from an ancient German noble family (their lineage can be traced back to at least the middle of the 15th century). His mother, Anna Laura von Steffens, came from the Rhine provinces. Franz was their third child. The family was Catholic, and many years later von Papen would pathetically lie that he "fought Hitler's policies" as a man of faith.

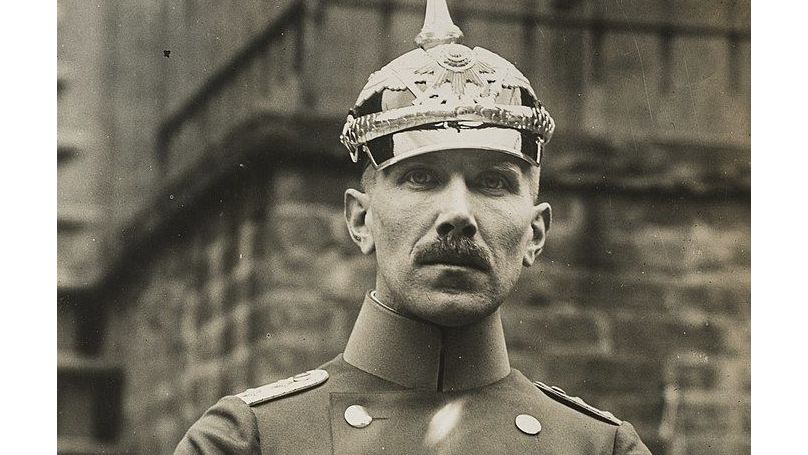

At the age of 11, his parents, who generally saw their son's future in law, medicine, the priesthood or, at the very least, the civil service, were forced to give in to his stubborn pleas and send him to a cadet school. Franz braved severe drills, did well in the classroom and did not disgrace his family, constantly receiving confirmation of the correctness of his choice – he was trained as a Herrenreiter ("gentleman rider") and was made an officer before others. As a young man, he attended imperial balls, opening ceremonies of the Reichstag and the Prussian Landtag (the parliament of states in Germany and Austria) and came face to face with prominent figures in the Kaiser's empire.

After the cadet school and then the officer course at the Prussian Main Military Academy in Lichterfelde, Franz served as a second lieutenant in his father's old unit – the 5th Westphalian Uhlan Regiment in Düsseldorf, where the elite of the elite, from the best families, had gathered. Indeed, this was how his life would unfold in the future - at every turn of fate, von Papen found himself in the most elite company (with a proviso: whatever that "elite" might be). He had mastered all the skills befitting a German officer – he became, for example, a brilliant rider and even took part in races as an amateur jockey.

In 1913, von Papen joined the German General Staff as a captain. By this time he was already married – quite in the tradition of his class. His wife was Martha von Boch-Galhau, one of Germany's richest brides, the daughter of a Saarland industrialist who owned Villeroy & Boch. Her dowry and inheritance made von Papen a very rich man. He himself fully embodied the "cream of the military caste".

Aristocratic origin and upbringing, sumptuous posture, excellent education, wealth, a broad outlook, fluency in several languages, unconditional personal charm, and influential friends... He also had a very particular personal philosophy that combined snobbery (an undisputed belief in the superiority of the aristocracy over plebs), loyalty to Kaiser Wilhelm II, monarchism and military views, once and for all shaped by the books of the legendary General Friedrich von Bernhardi.

Saboteur Diplomat

In December 1913, von Papen made a major career leap - he entered the diplomatic service. And, right away, as a military attaché to the German ambassador to the United States. And from that moment on any personal integrity and professional sensitivity was out of the question. In 1914, he went to Mexico to observe the revolution there. He had earlier organised a group of European volunteers to help the rebellious Mexican General Huerta and was now selling him arms in the hope of getting Mexico into the German sphere of influence. These plans never came to fruition, with the US suppressing the coup in Veracruz. On the other hand, von Papen got his first taste of adrenaline - and he enjoyed organising international intrigues. From that moment on, this is what he engaged in.

During World War I, von Papen, for example, tried to procure arms from the neutral United States but ran into a problem: the British blockade prevented arms from reaching Germany. Von Papen then hired a local private detective to sabotage Allied businesses in New York.

Berlin had provided its attaché with unlimited funds and now, since it was impossible to buy arms for Germany, he tried to prevent Britain, France, and Russia from doing so. He went so far as to register a front company that tried for two years to pre-buy every hydraulic press in the United States in order to prevent American companies from producing artillery shells for the Allies. Moreover, during the same period, von Papen organised the manufacture of false American passports in New York so that German citizens from North and South America could return to Germany.

He eventually went too far, seized by adventurous excitement and assured of impunity. Towards the end of 1914, he abused his diplomatic immunity and began planning an invasion of Canada with the bombing of the main transport routes - railways and bridges. He also took part in the Hindu-German Conspiracy – he contacted anti-British Indian nationalists in California and supplied them with arms. In 1915, he organised the Vanceboro international bridge bombing and avoided arrest because of his immunity. In the meantime, he continued to supply arms to the Mexicans.

British intelligence got tired of witnessing it alone and submitted all their information about the pranks of the German military attaché to the US government. They did not hesitate to declare von Papen persona non grata and expel him from the country for complicity in planning acts of sabotage, espionage, and subversion. In Germany, the modest hero was met with applause and immediately awarded the Iron Cross.

By the way, he did not shy away from conspiracies in America later on. He kept turning the tables on the options for seizing influence in Mexico. He supplied arms to the Irish Republican Volunteers for the Easter Uprising against Britain in 1916 and maintained intermediary links with Indian nationalists.

Astonished at watching this, the American authorities eventually decided to express little more than deep concern, and in the spring of 1916, a US federal grand jury indicted von Papen for conspiracy to blow up the Canadian Welland Canal. However, the charge was later dropped - surprisingly, it coincided with von Papen's rise to the position of chancellor of Germany.

Chevalier of the Iron Cross

After satisfying his passion for international intrigue and playing spies for a while, Franz decided to shake off the old days and recall his military skills. He returned to active service on the Western Front. And, it must be said, he fought to his heart's content, though not too successfully. In August 1916, Papen’s battalion suffered heavy losses while heroically repelling a British attack during the Battle of the Somme, and a year later was defeated by the Canadian Corps at the Battle of Vimy Ridge. By this time von Papen had been awarded the Iron Cross, 1st Class. He was indeed as brave as a lion and did not hide from bullets.

Later, he was transferred to the Middle East and served as an officer in the Ottoman Army in Palestine (the Armenian genocide, which von Papen had witnessed, did not affect him at all). It was in Constantinople that he, now a major, became close friends with Joachim von Ribbentrop. He again proved himself to be a fearless warrior – in the heavy fighting in the Sinai and Palestine campaign. He returned to Germany in November 1918 after the armistice between the Turks and the Allies with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Here, too, courage had its place. Before the withdrawal of the German Asia Corps, the order came for the creation of soldier's councils in the German Army, including the Asian corps, which General Otto Liman von Sanders attempted to obey, and which Papen refused to obey. General Sanders ordered Papen arrested for his insubordination, but the disobedient lieutenant colonel left his post and fled to Germany in civilian clothes, there meeting Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and convincing him of his utmost loyalty.

German Gentlemen's Club and 'Cabinet of Monocles'

Bored after a year of serene country life following the army, von Papen went to the Ruhr to suppress the Communist uprising as commander of the Freikorps and protect Roman Catholicism from the "Red marauders". He so impressed the "right people" that in the autumn of 1920, Baron Engelbert von Kerkerinck zur Borg, the president of the influential Westphalian Farmers’ Association, promised von Papen support if he decided to run for the Prussian Landtag. He did not miss his chance.

He joined the Centre Party, better known as the Zentrum, on the side of the extreme conservative Catholic wing. He immediately proved himself to be a hard "right-wing" politician and took a leading position in the Zentrum because he had serious resources – he was the largest shareholder and chief of the editorial board of the country's most prestigious Catholic newspaper Germania.

For a total of ten years, von Papen represented Westphalia in the Landtag. However, he seldom attended meetings and never made a speech. Finally, he managed to turn his own party against him: in a presidential election, he voted for the right-wing candidate Paul von Hindenburg instead of the Zentrum candidate Wilhelm Marks. Party members were so enraged by this betrayal that they almost expelled von Papen for breaching party discipline.

His passion for conspiracies had reared its head again by this time – von Papen became a member of the secret, exclusive Berlin Deutscher Herrenklub (German Gentlemen's Club). This was where ambitious, cunning politicians formed small coalitions, made friends against someone, and devised devious intrigues. All of von Papen's former noble integrity had long since vanished.

Therefore, the recent monarchist welcomed a presidential government in 1930 and shrewdly supported the NSDAP. And in the presidential elections of 1932, he voted for his former comrade-in-arms Oskar von Hindenburg as the ideal candidate to unite the right-wing. On 1 June 1932, Franz von Papen became chancellor of Germany.

Papen owed his appointment to the chancellorship to General Kurt von Schleicher, an old friend from the pre-war General Staff. Schleicher, who became Defence Minister, also selected the entire Cabinet himself, subsequently nicknamed "the cabinet of barons" or "cabinet of monocles". It was not without another betrayal – von Papen, who had assured his fellow party members the day before that he would never allow this to happen, complied with Schleicher's wishes. In June 1932, he met Adolf Hitler.

Chancellor, Who Annoyed Everyone

Hitler and Hindenburg then agreed that the Nazi Party would not object to the "cabinet of monocles" if: new elections were called, the ban on stormtroopers was lifted and the Nazis were given access to the radio. All demands were met.

As chancellor, von Papen immediately demonstrated his unscrupulousness at an international level. He attributed the success of the cancellation of the enormous German reparation obligations to himself, but at the same time, he retroactively breached the terms of this cancellation and refused to pay 3 million Reichsmarks to France.

Ordinary Germans quickly took a dislike to the new chancellor: von Papen introduced austerity, reduced unemployment benefits, and at the same time reduced taxes for corporations. He had an uncanny talent for turning everyone against him - friends, colleagues, partners, voters... Von Papen, pretending to be a brilliant political strategist, was constantly taking the wrong decisions and outplaying himself.

That was how he suppressed a coup by the Social Democrats in Prussia on the unsubstantiated pretext of their alliance with the Communists, hoping to earn the support of the Nazis. Then he embarrassed himself at the World Disarmament Conference by telling the German delegation to leave when the French prophetically warned that giving Germany equal status in arms build-up would lead to a new world war.

On 31 July 1932, the Nazis won a majority in the Reichstag elections. In the wake of their success, the level of domestic political terrorism skyrocketed - SA militants felt impunity. Von Papen swung like a pendulum so as not to lose Hitler's favour - and, for example, commuted death sentences to life imprisonment for several stormtroopers who had murdered a communist worker in the infamous Potempa Murder.

At a press conference on 11 August, Constitution Day, von Papen announced plans for a new constitution, which essentially turned Germany into a dictatorship, and offered Hitler the post of vice-chancellor. The latter did not accept the handout – he wanted real power and was prepared to wait for it.

Intriguer's Mistake

In November 1932, von Papen quietly broke the Treaty of Versailles by adopting a programme to rebuild the German Navy – now battleships, cruisers, flotillas of destroyers and submarines, and even an aircraft carrier allowed Germany to control the North and Baltic Seas. However, this did not help his popularity, plus the Nazis lost their advantage in the Reichstag - and Papen was forced to resign. Schleicher now became chancellor, a former close friend who became an enemy.

The resentment hit von Papen so hard that he lost the ability to think logically. The main thing on his mind was to take revenge and return to power. To do this, he decided to play on Hitler's ambitions - strongly believing that he would be easy to control. The two of them met secretly and agreed to form a new government. Von Papen, proud of his craftiness, modestly agreed to serve as vice-chancellor under Hitler. The few sceptics, who saw Hitler as a threat, von Papen arrogantly reassured: he and the old Hindenburg had everything worked out and planned, the new chancellor would be "in their pocket". On 30 January, the president, who had recently sworn publicly that Hitler would never be chancellor, announced his appointment.

There were only three Nazis in the new Cabinet: Hitler, Göring, and Frick. The remaining posts were filled by conservatives close to von Papen. The vice-chancellor gained the right to be present at every meeting between Hitler and Hindenburg, all of the Cabinet's decisions were made by vote - in short, it seemed that the conservatives would be able to control the new chancellor. No such luck. Hitler and his allies quickly cornered von Papen and the rest of the ministers. The first thing they did was to make Göring Prussian Minister of the Interior and take control of the German police force. In doing so, Göring defiantly failed to make his formal superior aware of his decisions.

The vice-chancellor was now Hitler's lapdog and carried out all of his orders without question. All attempts at intrigue failed. Von Papen wanted to unite his new party, the League of Catholic Germans Cross and Eagle, with the Zentrum, and the Bavarian People's Party, to keep the NSDAP in check, but no one believed him and would not cooperate. In the spring of 1934, when President Hinderburg was already at death's door, von Papen drafted his political will, which provided for the dismissal of a number of Nazi ministers. Von Papen renewed his spirits.

Black Mark on the Night of the Long Knives

On 17 June 1934, Papen delivered an address at the University of Marburg. He did not coordinate the speech with anyone, and in fact, he first saw it two hours before the speech. The text was written by his assistants: secretary Herbert von Bose, speechwriter Edgar Julius Jung, and Catholic leader Erich Klausener. As a result, the audience enjoyed von Papen - he was on fire, campaigned for the restoration of former freedoms and demanded an end to the SA terror in the streets, criticised violence and repression with the chancellor's approval, appealed to the Reichswehr and the German financial and business elite, denounced NSDAP extremism, spoke openly about anonymous surveillance and intimidation of opponents by Hitler

Excerpts were published in Germany's most prestigious newspaper, Frankfurter Zeitung. Hitler became enraged and demanded that further publications cease. To which von Papen reacted with dignity for the first and last time in his life - he announced his readiness to resign immediately. But Hitler suddenly backed down and peacefully acknowledged that criticism of the regime was quite appropriate and useful, assuring that the demands made in the speech would be met. Von Papen bought it and did not even remember the chancellor's vengefulness.

Two weeks later, Hitler set about purging the SA and eliminating the "top brass", led by Röhm. The Night of the Long Knives continued from 30 June to 2 July. It was then that the SS attacked Papen's office in Borsig Palace, the office was seized and searched by the Gestapo. That night, von Papen lost all of his assistants who had written the Marburg speech. Bose, Jung, and Klausener were shot dead.

The vice-chancellor was placed under house arrest and had his telephone line cut off. He was not killed, as von Papen himself later claimed, only thanks to Göring personally, who believed that the former diplomat could still be useful. The police officers guarding von Papen were subordinate to Göring and had orders to prevent his arrest by the Gestapo or the SS. After three days under house arrest, during which he did not sleep a wink, the vice-chancellor presented himself to the Reichstag. There he found Hitler and the Nazi ministers meeting at a round table, with no room for him, von Papen. He lingered, then asked for a personal audience with Hitler and resigned. On 2 August, Hindenburg died and there were no more obstacles for Hitler.

Even Nazis Despised Him

Much later, when the matter came up at the Nuremberg Trials, the defendants would not hide their contempt - how could anyone go back to work with Hitler after the open murder of your loyal colleagues and aides? At the trial, a letter written by von Papen to Hitler immediately after the Night of the Long Knives would be read out, with assurances of support, admiration for the "heaven-sent German leader", and praise for the courage and determination with which the chancellor "heroically crushed Röhm's putsch". Göring loudly called von Papen a "liar" and a "coward". And Jodl added:

"If I had allowed three of my adjutants to die, I could no longer serve this regime! You should have swallowed poison after that!" Prosecutor Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe would throw at the defendant: "You were prepared to serve these murderers so long as your own dignity was put right! You realised that after a murder that caused such an international backlash, the support of the ex-chancellor, who enjoys prestige in Catholic circles, was invaluable to Hitler!" – "Although this is true", replied Papen, "if I had started working against him, I would inevitably have met the fate of my missing colleagues". Afterwards, he would complain to psychiatrist Gustave Gilbert: "Naturally, you look at everything completely differently now than you did then, and after being arrested for three days. All these questions – why or what for I stayed in the government... I want to ask you again - what else could I do when the war broke out? (...) My God, after they shot my own assistant! —And yet I had to say to myself: 'You still have your duty to the Fatherland!'—Do you think it was easy? It was a terrible conflict!"

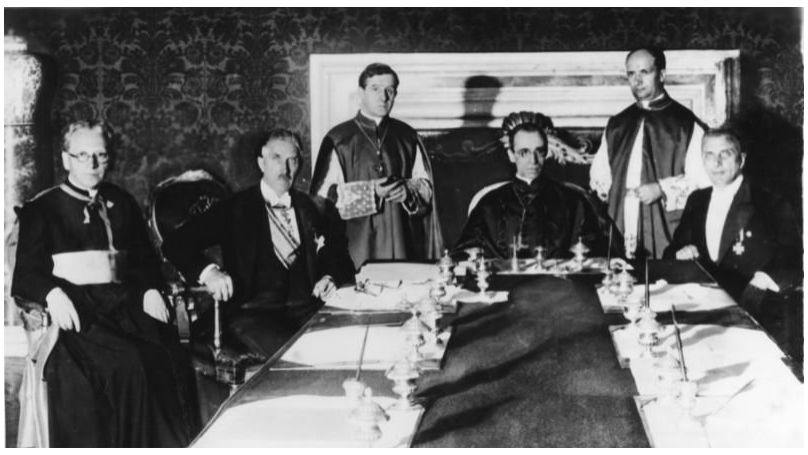

As a consolation, Hitler gave von Papen an NSDAP Golden Party Badge and appointed him ambassador to Austria. There, through successive deceptions, threats, flattery, and bribery, von Papen set about preparing the Anschluss, the annexation of Austria by Germany. The new ambassador regularly assured Chancellor von Schuschnigg that Germany had no intention of annexing Austria. All that was needed was for the local Nazi Party to be allowed to participate in state politics. He then raised the pressure - and arranged for a 1936 agreement, whereby Austria declared itself to be a German state and undertook to coordinate its foreign policy with Berlin.

In return, Germany would swear that it had no intention of annexation. By the end of 1937, von Papen had established a strong Nazi presence in the Austrian government. He was then recalled to Berlin and entrusted with organising Italian-German negotiations with Mussolini. In the meantime, Hitler had stepped on the ground prepared by the former ambassador, delivered an ultimatum to von Schuschnigg, forced the Austrian government to capitulate, and opened the way for the Anschluss.

Ambassador with 'Carrot and Sticks'

Von Papen served as German ambassador to Turkey from 1939 to 1944. His appointment was resisted for a year by Turkey's President Mustafa Kemal, who recalled with disgust their common service in World War I. His successor, Ismet Inönü, also vetoed Ribbentrop's attempts to install von Papen in Turkey for several months. But in the end, he gave in.

The new ambassador arrived at the end of April 1939, just after the signing of the UK-Turkish declaration of friendship: President Inönü wanted to join forces with Great Britain against Germany. In July, Turkey and France signed a declaration on collective security in the Balkans. And in August, von Papen showed his teeth - he presented Turkey with a diplomatic note promising economic sanctions and cancellation of all arms contracts if the friendship with the UK-French "peace front" did not end.

On 1 September 1939, Germany attacked Poland, and on 3 September Britain and France declared war on Germany. Von Papen would later state at every opportunity that he strongly disagreed with Hitler's foreign policy and was shocked by the invasion of Poland, and did not resign at the time solely for reasons of loyalty to the country - his demarche indicated to everyone the "moral weakening of Germany".

In June 1940, France was occupied and Inönü gave up pro-alliance neutrality. By 1942, von Papen had concluded three economic agreements that placed Turkey under German economic influence. As an effective threat, he constantly signalled that Germany would support the Bulgarian claim to Thrace in the event of disobedience. In June 1941, he signed a Treaty of Friendship and Non-Aggression with Turkey, and thus drove a wedge between it and the Allies. After the invasion of the Soviet Union, he insisted that Turkey close the straits to Soviet and British warships.

He would later claim that he went to great lengths to save Turkish Jews in the occupied countries from being sent to concentration camps, even mentioning a figure of 10,000, but this was never confirmed. However, he was confirmed to have persuaded Turkey to join the Axis countries throughout World War II and to have spent huge sums of money from special funds to bribe influential Turkish politicians.

On 24 February 1942, an assassination attempt was carried out on von Papen. A bomb was detonated, but only the saboteur was killed. The ambassador was slightly injured. This may have been done by NKVD agents on Stalin's personal orders, furious at the closure of the straits to ships. A second theory was that the attack was ordered by Hitler, so that suspicion would fall on Soviet agents.

In 1943, von Papen disrupted British negotiations with Turkey and their allied cooperation. The usual carrot and stick method worked: the ambassador arranged a letter from Hitler assuring Inönü that Germany was not interested in invading Turkey, and threatened the Luftwaffe would bomb Istanbul in case of disobedience.

By the summer of 1943, von Papen realised that Germany's defeat was inevitable. Once again he began to intrigue. He managed to arrange a meeting with the Americans in Istanbul and asked for US support, shamelessly offering his candidacy for the role of the dictator of Germany after the elimination of Hitler. But Roosevelt, on hearing of this, immediately forbade any talks with von Papen.

Now he had to use the stick more often - the carrot no longer had any effect on the Turks. When he learned of British plans to use Turkish airfields to bomb Romania, he threatened that in response the Luftwaffe would destroy Istanbul and Izmir from their bases in Bulgaria and Greece. But it was agony; they were no longer feared.

Since the spring of 1944, Turkey had reduced its exports to Germany by 50 percent, and on 2 August it broke off diplomatic relations. Von Papen was forced to return to Berlin. An attempt was made to send him as ambassador to the Vatican to Pope Pius XII, but the Pope categorically rejected the appointment.

Not to See Germany's Shame

In August 1944, von Papen met Hitler for the last time. He was awarded the Knight's Cross of the War Merit Cross. From September of that year, the former diplomat licked his wounds at his estate in the Saarland. From there he fled inland with his family as early as November, in fear of the advancing US Army. In January 1945, he appealed to Ribbentrop's deputy: let him, an experienced diplomat of the old school, be sent as an intermediary to persuade the Western powers to prevent the Russians from occupying Germany. But to no avail.

On 14 April 1945, Franz von Papen was captured along with his son Franz Jr. in his own home in the Ruhr by soldiers of the US 194th Glider Infantry Regiment. Before his imprisonment, he was taken to a concentration camp to see with his own eyes the things he had served and contributed to.

He learned and saw a lot at the Nuremberg Trials. Or maybe he pretended it was new to him. He turned away from the screen when a chronicle of the death camps was shown ("I don't want to see the shame of Germany!"). After each hearing, he would rant for hours, denouncing Hitler and his dock mates and readily accepting the accusations made against them all... except him. He was not guilty of anything but did it out of love for his long-suffering homeland. In his conversations with Gilbert, he lamented:

"Oh, but who took Mein Kampf seriously, my dear professor? People write so many things for political purposes. I had my differences with him, but I never really thought he meant war until he broke the Munich agreement. He removed me from the Austrian posts five weeks before the Anschluss, because he had decided not to go along with my evolutionary policy. (…) What could I do? Leave the country and live as a foreigner? I didn't want that. Go to the front as an officer? I was too old, and anyway, shooting isn't in my line. To denounce Hitler would of course simply have meant being stood against the wall and shot, and it would not have altered anything!"

By Lesya Orlova

Sources:

Franz von Papen, "Memoirs", published by A. Deutsch, London, 1952.

Gustav Gilbert, "The Nuremberg Diary", published by New American Library, New York, 1961.

Konstantin Zaleski, "Who Was Who in the Third Reich", Biographical Encyclopaedic Dictionary.