Those who attended the Nuremberg Trials could never quite satisfy themselves on the question of whether the defendants were truly mentally normal. Could it be that they were all maniacs, psychopaths, deranged sadists? And sure enough there were those among the staff of the International Military Tribunal who had to decide this on a professional level – psychiatrists and psychologists. There were three in particular who played a vital role in assessing the mental state of the criminals from whose acts the civilised world shrank in disgust. They were all American and two of them were Jewish and their experiences, which made them international stars, haunted them to their dying day. They were Douglas Kelley, Gustave Gilbert and Leon Goldensohn. Day after day they explored the paradoxes of Nazi psychology and grappled with the subconscious of history's greatest villains. But the conclusions drawn after numerous tests and extensive examinations dismayed even the experts.

Unanswered Question

On 1 January 1958, the Kelley family was preparing dinner before watching the traditional New Year's Rose Bowl game in Pasadena, California - near their home in Berkeley. Dr Douglas Kelley, a renowned forensic psychiatrist, was helping his wife cook. Suddenly an argument burst out over a trifle, the 45-year-old doctor burnt himself and rushed out of the kitchen in a rage into his office. From there he sprang up the stairs almost immediately, shouting, “I can't go on like this, I can't do it!”, adding that he would be dead in 30 seconds. His aged father, wife and eldest son begged him to come to his senses, but Kelley hastily swallowed something and disappeared into the bathroom where, moments later, he was found dead on the floor, frothing at the mouth.

This story might seem surreal if one was unaware that Dr Kelley had worked as an expert psychiatrist at the Nuremberg Trials where he had become, in a sense, obsessed with Hermann Göring. He admired the way Göring committed suicide by taking potassium cyanide and it was a vial of cyanide capsules found in Kelley’s fist when his fist was unclenched.

More to read

This was the answer everyone was looking for at the Nuremberg Trials. Everyone who was exposed to the truth about Nazism in all its shocking immensity in those days, everyone - from the judges to the stenographers, from journalists to guards - sought to understand what went on in the minds and hearts of the two dozen seemingly normal people sitting in the dock. Were they even normal? Could it be that they were all just crazy?

Prison psychiatrists and psychologists had to find out - to assess their sanity, their intellectual level, their capacity for empathy, and the quality of their emotional and social intelligence. And thus three men went down in history: Gustave Gilbert, Leon Goldensohn, and Douglas Kelley, each leaving behind a book as testament to their remarkable findings, respectively ‘The Nuremberg Diary’, ‘22 Cells in Nuremberg. A Psychiatrist Examines the Nazi Criminals’, and ‘The Nuremberg Interviews’..

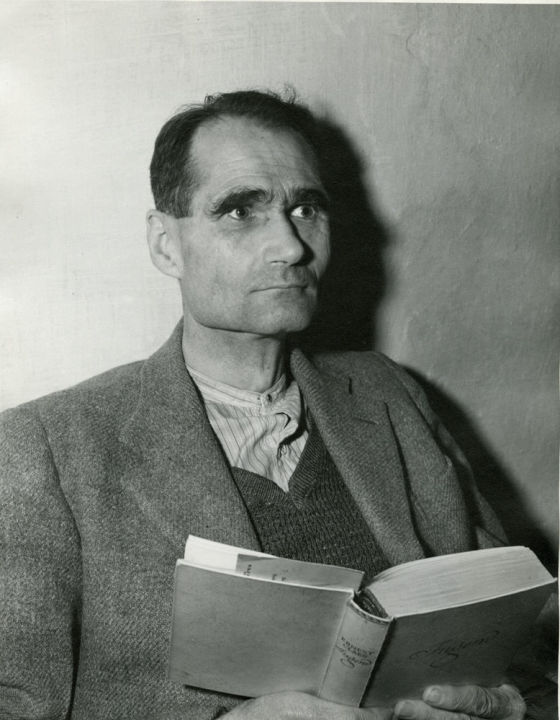

Douglas Kelley, ‘Possessed By Darkness’

Lt Colonel Douglas McGlashan Kelley, a military intelligence officer, was born in 1912, graduated from the University of California at Berkeley and received his doctorate in San Francisco. He served in the US Army Medical Corps from 1942 (treating American soldiers in Europe for combat stress), and in 1945 he reached the pinnacle of his career, being appointed chief psychiatrist at Nuremberg Prison during the Nuremberg War Trials. His job was to examine and prepare a qualified opinion as to whether the activities of the defendants were the result of mental aberrations or the manifestation of some characteristics and inclinations of a pathological nature.

Kelley kept detailed "histories" of each defendant, recording in detail their condition: from physiological measurements such as pulse, heartbeat and temperature, to changes in mood, social and character traits. He had his original hypothesis - Kelley set to work, almost certain that he would quickly confirm that the Nuremberg defendants were simply abnormal. It was not only his humanity but also his cool and detached professionalism that told him that abnormalities were bound to exist. It could not be otherwise – mentally healthy people could not systematically, regularly and deliberately do "such things".

By the way, his fellow psychologist and fellow American, Gustave Gilbert, disagreed with Kelley. He was "betting" that the research would prove that the mental and psychological features of the accused were not abnormal. However, there was no time for long discussions: the work was extremely intense and tremendously demanding, with many hours of daily discussions with the defendants, and the need to maintain professional ethics and a completely non-judgemental attitude and neutrality throughout.

High-ranking Nazis enjoyed their communication with psychiatrists and psychologists. It gave them a renewed sense of their own importance, allowed them to speak out, complain, accuse and justify themselves, and gave them the comfortable illusion of cooperating with benevolent supporters. They were asked questions, they were listened to, their intelligence and emotional competence were tested interestingly - and they willingly completed all tasks, and took every opportunity to explain themselves, talk about themselves, and evoke sympathy and empathy for themselves.

Kelley’s son, Douglas Junior, has kept 12 boxes of his father's archives. They contain diaries, notes, photographs and even an upholstered velvet jewellery box with a vial labelled “Hermann Göring’s Paracodeine" containing a drug of good wine – over 65 years old. The boxes also contained X-rays of former Nazi Reichsorganisationsleiter Robert Ley's brain and even pictures of Hitler's skull, from eight angles, apparently given to Douglas Kelley by the Führer's personal physician, Karl Brandt, because he was concerned about his chief patient's sinusitis.

Kelley may have delved deeper into the dark waters of the psyche of his "Nuremberg patients" than anyone else. He was troubled by Hitler's personality and sought explanations for his destructive nature. Repeatedly he spoke to Karl Brandt as to a colleague who might shed some light on the mystery. Eventually, Kelley decided that Hitler was normal, but suffered from hypochondria, which provoked the most monstrous decisions and ideas. For example, at one point the Führer convinced himself that he was sick with stomach cancer – and that was supposedly why he hastened the attack on the USSR. Literally, he wanted to “make it happen in his lifetime”.

The preconceptions Kelley had established about his work were shattered by the inexorable reality. Expecting unconditional manifestations of pathology, perversion, and deviance, he was repeatedly horrified to find that he was simply looking at people who had in some incredible way combined normal inclinations, passions, and feelings with inhumanity on an unprecedented scale.

But most of all, Kelley was captivated by the charisma of Göring, who was certainly distinguished by his uncharacteristic strength, conviction and courage. One might perhaps say that the psychiatrist fell under a bad spell - in the same sort of way that Clarice Starling in ‘The Silence of the Lambs’ feels inexorably drawn and enthralled by the powerfully charismatic genius she is interrogating, Hannibal “The Cannibal” Lecter. Kelley became the Go-Between, delivering Göring's letters to his wife and daughter and returning with their replies. Naturally, he read everything - and he was utterly overwhelmed by the love, tenderness and caring that permeated every line written by the monster.

Douglas Kelley would probably have been saved these days by the modern techniques of psychiatrists and psychologists – supervision, the opportunity to offload, channel and reflect on impressions in close contact with a professional. At the time, however, he was left to his own devices and the Nuremberg experience was a genuine timebomb that Kelley carried around inside him without hearing the quiet ticking. It seemed to him that he and Göring were very similar – two narcissists with outsized egos – both strong-willed and spiritual, egocentric and extremely individualistic. And if so, if the similarities are so obvious - doesn't that mean that Kelley himself was harbouring the same potential for evil? His shift from clinical psychiatry to forensic science not only did not help, but exacerbated his doubts and deepened his inner conflict. Kelley no longer saw a clear boundary between himself and the objects of his research. A shadow personality, a darker side, stared at him more and more out of the mirror.

Upon his honourable discharge in 1946, Kelley was appointed Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the Bowman Gray School of Medicine in North Carolina and, three years later, Professor of Criminology at the University of California at Berkeley and President of the Society for the Advancement of Criminology. He hosted his own television show, ‘Criminal Minds’, and while doing so, descended rather quickly from being a regular drinker to an alcoholic - withdrawn, irritable and suffering from "gloomy moods of a suicidal nature". Since his return from Nuremberg, he had strictly forbidden his wife and three children to ask him any questions about his work at the tribunal or his experiences.

At the news of Goring's suicide, Kelley was unable to conceal... his admiration. In the act of his anti-hero, he saw not the cowardice of the loser, but victory wrested from the most hopeless circumstances as he retained control over his own life and death, desperate courage of the ultimate individualist, a grandmasterly surprise move that wrong-footed everyone. Was he to be hanged as a common criminal? He did not allow such a chance – he left life then and there, as he pleased.

Twelve years later, the 45-year-old Douglas Kelley followed in the footsteps of Göring - the way Göring had chosen. What exactly was it that he “couldn't do anymore”? Perhaps living with the consciousness that he could easily do evil to others? Or was he overpowered by the shame of his mixed feelings? Or maybe he just couldn’t cope any longer with the realisation that the boundaries had become impossibly blurred.

Gustave Gilbert, ‘The Main Diary of Nuremberg’

Writer Arkady Poltorak, a member of the Soviet delegation, wrote in The Nuremberg Epilogue: “Right from the start I noticed the defendants talking often to a young American officer wearing the insignia of Internal Security Office("ISO"). He was the court psychiatrist, Dr G M Gilbert, [Poltorak pronounces Gilbert's name in the phonetic transcription of the Soviet school of the time – ed.]. In Nuremberg, he was envied by journalists from all over the world. Like all of them, Gilbert could listen to and observe what was happening in the courtroom. But unlike the rest of them he was able, without any restrictions, to communicate with the defendants at any time, both in the courtroom and in their prison cell, both in public and in private.

“Dr Gilbert had a good command of German, which was said to be his mother tongue. This further empowered him. He knew much that others did not. Journalists literally stalked him down, hoping to get something sensational out of him for the press. But Gilbert could keep his mouth shut. Just before the end of the trial, he told me that he was finishing processing his diaries and that several western publishers were putting pressure on him to do so. He was keen to get Soviet publishers to buy the manuscript as well. Gilbert gave me the first half of it to review. I read the whole book later. It was published in the United States and many European countries. In its own way, it is an interesting document, especially for those involved in the process. Gilbert paints the overall picture of what was seen at Nuremberg with many vivid details told to him by the defendants in private conversation. It is like a daily commentary by the defendants themselves on every significant event of the trial, explaining to some extent their own behaviour in court. Gilbert proved to be a keen observer.”

Gustave Mark Gilbert, the son of Jewish-Austrian immigrants, was born in New York in 1911. In 1939, at the outbreak of the Second World War, he was awarded a Doctor of Philosophy degree in psychology by Columbia University. As a graduate student, he published studies on the relationship between the senses and memory. His German was fluent and he fought in the war, serving as a First Lieutenant in military intelligence. After the Normandy landings, he was sent to Europe among army officers and interrogated captured German officers. Immediately after the end of the war, he was sent to Nuremberg. The US government openly regarded the trial not just as a trial, but as a psychological laboratory in which inhuman barbarism in its most extreme form was clinically investigated and proved. Gilbert was ambitious, and he quickly recognised the work at the Tribunal not just as a duty but as a major chance in life.

More to read

The defendants, perhaps, preferred Gilbert to anyone else - they trusted him, shared all their worries with him, sought his sympathy. In a sense, they had become like children, clinging to an adult, and very soon they were no longer embarrassed by him and trying to save face. As people of the Freudian era, they experienced the notorious 'transference' state described by him - they turned all their feelings towards their listener. Meanwhile Gilbert himself - again, like few others - for all his outward benevolence, managed to remain indifferent both to the charm and the most repulsive manifestations of his objects under observation.

Before his eyes, Ribbentrop slipped into an almost animalistic condition of panic meltdown, Hans Frank suffered a severe spiritual crisis, von Papen finally lost his composure and Albert Speer dared to face the truth. Before his eyes, the defiantly unapologetic gang disintegrated into two dozen losers, the seemingly indestructible group fractured into 20-odd loners who hated each other: internal conflicts, alliances which were revealed to be momentary coalitions, mini-boycotts and whispers quickly became a daily reality of Nuremberg Prison. Everyone tried to get hold of Gilbert in the hope of gaining his support. But he only wondered to himself: men who until recently had dared to take ownership of the world now refused to take responsibility – except for Göring, with his consistent pride in defending the ideals of the past.

His work at Nuremberg made Gilbert famous. After that, he taught at Princeton, the University of Michigan and Long Island University. And in 1961, he spoke in Israel at the trial of Adolf Eichmann, as an expert witness. It was the trial of SS executioner Eichmann and his role in the Holocaust that would lead Hannah Arendt to coin that ingenious phrase, the “Banality of Evil” - a neat and unbeatable answer to the baffled question of “how on earth could they?”

Gilbert would write several works, including one expounding on the personality of Göring, and the other, ‘The Psychology of Dictatorship’, analysing the phenomenon of Hitler. However, in the Sixties his star waned and he was toppled from his pedestal as the chief expert on “Nazi consciousness” after being outshone by a young psychologist, Stanley Milgram, who set up a programme of laboratory experiments investigating the Holocaust. After two decades, observers switched their interest to the idea of turning an ordinary American into a virtual Nazi rather than to study the confessions of real Nazis. Milgram became famous as an expert on "malignant authority figures" and Gilbert practically disappeared from a scene he had dominated with such flair. He died at the age of 65 in 1977. However, his books are still highly regarded by historians and he is regularly immortalised in literature and films about the Nuremberg Trials.

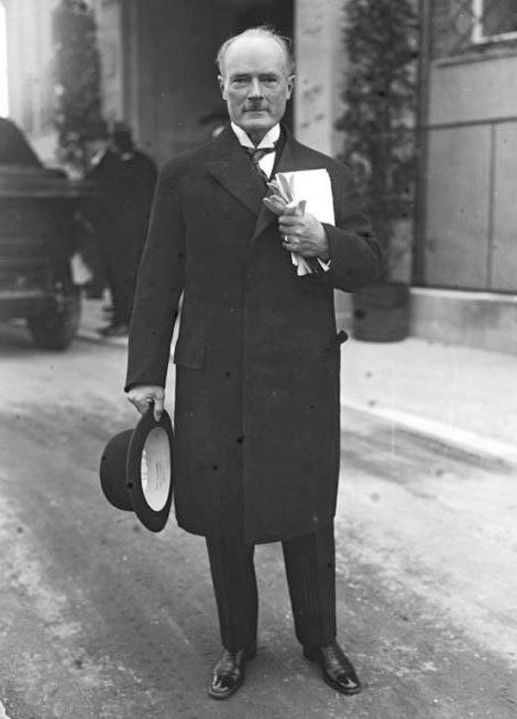

Leon Goldensohn, The Jewish Confessor

Leon Goldensohn, a psychiatrist, took over from Douglas Kelley and worked with the defendants in the final six months of the Nuremberg Trials. This irony of the situation was not lost even on the highest-ranking Nazis who still clung to the delusion of their blamelessness. The choice of Goldensohn, a Jewish native of New York whose family had emigrated from Lithuania before his birth in 1911, was seen as truly divine retribution. The most depraved of the Nazi criminals were now compelled to be analysed by this 34-year-old man, who had served during the war in the US Army’s 63rd Division in France and Germany. Now, these butchers who had caused the death of millions who shared his ethnicity were on the block themselves, as he assessed their mental health: the commandant of Auschwitz, Rudolf Höss, Third Reich Foreign Minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Nazi Editor of the notoriously anti-semitic newspaper ‘Der Stürmer’, Julius Streicher, commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe (German Air Forces) Hermann Göring - all were now at his mercy. Goldensohn spoke at length with each prisoner, as well as with the many witnesses at the trials, about the Holocaust - it was not only a professional necessity, it was the main issue that tormented him.

More to read

The interviews conducted by Goldensohn with the defendants at the Nuremberg Tribunal were extremely representative. Reich Minister for Economic Affairs, Walther Funk, calmly said: “There was too high a percentage of Jews in the legislative, economic and cultural life of our Reich. But I was not a radical! I did not foresee the massacres.” Similar views were echoed by Germany’s Ambassador to Austria, Franz von Papen, who said: “Hitler did not seek to exterminate the Jews. He just said at the beginning that the Jewish influence was too great. You see, after 1918, when we lost the war, we had a large influx of Jews from the East. This oversaturation was totally abnormal for the country! We thought it had to be corrected”.

Alfred Rosenberg, who oversaw the occupied German territories, lamented that the Jews were “spitting at German culture”, controlling “theatre, publishing, commerce and so on”. Even on the gibbet about to face the gallows they denied responsibility for the mass murders, but were unable to reject the basic thesis of anti-semitism - the existence of a “Jewish question”.

The prison psychiatrist was not in charge of treatment, only observation. The results - the characteristic and important utterances of the defendants - were duly recorded by Goldensohn, who did his best to maintain a scientist’s objectivity. He asked Höss how it felt to order the extermination of children who were the same age as his own who were virtually living there, in a concentration camp. And Höss, who has sent 2.5 million people to the gas chambers and ovens, nonchalantly replied: “I did not kill anyone myself. I simply directed the extermination programme”.

Göring pathetically argued that genocide was against his "code of chivalry", that he "respected women and considered it non-sporting to kill children" and that "no one knew the real Göring". On the other hand, Hans Frank, the Führer's lawyer, the "Butcher of Poland", sang Hitler’s praises, suggesting that he had abnormal sexual needs and that his sadistic tendencies resulted from his lack of love of women – and Goldensohn recorded these theories with a straight face as though it was “from one colleague to another”. Listening to Ribbentrop, he quickly made a note: “that the utterly two-faced, fluid and volatile-as-water hypocrite is not so much still under Hitler's spell as he is making a calculated effort to create the myth of his irresistible personal magnetism.”

Upon his return to the United States, Goldensohn delivered several lectures about the Nazis under his charge and was about to write a book about this unprecedented and eye-opening experience. But he didn't make it in time; he died aged 50 of a heart attack in 1961.

For some reason, the Goldensohn family treated his legacy as if it were a hot potato that was hurriedly tossed from hand to hand. Perhaps it was the fear of not being able to cope with the concentrated poison enclosed in his boxes of papers? His widow passed on her husband's archive to her children - two sons and a daughter - from the late Seventies to the mid-Eighties. They eventually passed the notebooks and typewritten copies of the interviews to their uncle, Goldensohn's brother Eli.

They would later openly admit that, if not for his efforts, Leon's work would never have seen the light of day. And even here, luck was on their side: Eli Goldensohn, a professor of medicine, had had a long enough life and the necessary skills to work with the archives. He retired at the age of 84 after completing his career as a practising neurologist and research scientist. He finished his own book and only then began his late brother's work. He transcribed his many detailed notes, studied them carefully, organised and summarised the material, spending more than five years doing so. And he published a thick tome, ‘The Nuremberg Interviews’, 60 years after Leon Goldensohn had repeatedly descended into Nazi hell and interviewed the greatest sinners in history. Why did they talk to a Jew, why were they frank with the enemy, the representative of the hated victors? Eli Goldensohn answered succinctly: his brother was a professional of the highest calibre, an intellectual capable of maintaining a conversation on any level, and a true gentleman. However, Leon's early death, according to Eli, was also on the conscience of the Nazis: what Leon had heard had inflicted wounds which would never heal.

Each and Every One Within the Normal Range

Kelley and Gilbert conducted a variety of different tests. For example, the famous Rorschach test: looking at cards with differently shaped inkblots and then saying what they resembled or what they made one think about. At the time, the Rorschach test was considered one of the most valuable psychological tests. For instance, those who saw dynamics, movement and process in pictures were considered to be more creative individuals. And those who saw plants, animals or natural phenomena were considered more "interpersonally isolated".

The results on the Nazis were intriguing: all the defendants were found to be utterly devoid of imagination and any creative ability whatever. Even those who, like the chief financial expert Hjalmar Schacht, indulged in verse-writing, or were good at drawing, such as the Third Reich's architect and Armaments Minister Albert Speer, nevertheless, the tests showed no deviation. All were “normal”.

The defendants also had to undergo an IQ or intelligence quotient test. Scores aren’t set in stone and depend greatly on the population of the sample but in general 128 and above indicates outstanding ability to the point of genius, a score of 80 to 119 indicates the standard, and a score of less than 65 indicates serious intellectual problems. The tests were carefully designed with adult subjects in mind. IQ levels were calculated to compensate for the natural deterioration of scores in proportion to the subject's age. In fact, the intelligence levels of the elderly, such as von Papen, Raeder, Schacht and Streicher (all of whom, apart from Julius Streicher who was born in 1885, were born in the 1870s), were 15 to 20 percent lower than the given figures, but fully in line with the data for their age group. Top scorers were Schacht (143), Seyss -Inquart (141), Göring (138), Dönitz (138), von Papen (134).

The result dazzled the psychiatrists: all the defendants easily passed the average mark. Even the lowest IQ score, Streicher’s, was still considerably above average. The overall average score of the 21 defendants was 128, which indicates high intelligence and originality (Göring, incidentally, was deeply offended at coming third and demanded a retest in the hope of getting top place after all). The results of the IQ tests were kept secret for a long time – they were not published in reports and it was sought to remove them from the discussion altogether: even the psychiatrists themselves found it difficult to accept the shocking fact that the greatest criminals in the history of mankind were really quite exceptionally intelligent people.

Another method of assessment used at Nuremberg was thematic perception tests – through narrative techniques hidden layers of the psyche are revealed. Gilbert also gave his subjects various tasks of a creative or analytical nature, such as writing an autobiographical essay, a commentary on a high-profile political event in the Third Reich, an explanation as to why certain steps were necessary, and even an attempt at an essay on one's own psychology. And the Nazis - the main and optional figures - willingly picked up their pens, flattered by the interest shown in their opinion, and set to it. For example, General Gerd von Rundstedt wrote an entire essay for Gilbert, entitled 'Was Hitler a Great General', in which he assessed the Führer's skills as a military commander and concluded that he lost the war because he listened not to the General Staff but to “irresponsible peace-lovers from party and propaganda circles”. SS Judge Konrad Morgen wrote an “apologia” on the psychological causes of the mass exterminations. As a result, he admitted in black and white that he knew about the atrocities in the concentration camps (although he tried to prove, rather confusingly, that he had somehow objected to them).

SS Obergruppenführer Oswald Pohl, the chief administrator of the Third Reich's concentration camp system, wrote an entire autobiography revealing many characteristics of Hitler and Himmler. Even the legendary and shocking autobiography of Rudolf Höss, a unique document about the dehumanisation of an entire nation, was written only as a result of Gilbert's insistence. Reich Minister of Economics Walther Funk wrote about Hitler's psychology, philosophy and ideology, and Hans Fritzsche, a member of the Nazi propaganda ministry, compiled a detailed psychological profile of Joseph Goebbels and described the extent of his likely influence on the German people. SS-Hauptsturmführer Helmut Fischer analysed in detail the organisation of science, higher education policy and relations between scientists under National Socialism. Gilbert's vast collection of handwritten documents would later be donated to the Yad Vashem Archives.

And so, having the test results, notes of the defendants and transcripts of interviews with them, the psychologists and psychiatrists struggled to unravel the most important question: were they dealing with pathology or with a monstrous deviation from the norm? What were the proportions of the “Nazi Virus” and consciousness of “evil intent”? Time and again the task converged with the answer. And time and again the psychiatrists and psychologists refused to believe their eyes.

The Battlefield: Back to Back, and Against Each Other

How impeccable were the conclusions of Kelley, Gilbert and Goldensohn from a scientific standpoint? For their time, they certainly used advanced technology. They made conclusions with confidence but, as would become clear decades later, there was a certain margin of error: ignoring the specifics of the sample. For example, they did not take into account how demoralised their “subjects” were and did not make adjustments for the conditions – prison, fear of retribution and execution. Moreover, psychiatry in the Forties was largely based on Freud's ideas, which were not yet applied uniformly; the experts at Nuremberg did not have a common psychiatric vocabulary. Therefore, the interpretation of Kelley and Gilbert differed considerably. The Rorschach test - then considered infallible - enjoyed no such credibility decades later. In the Seventies, Dr Molly Harrower, an expert in the Rorschach methodology, tested Unitarian priests and psychiatric outpatients and combined the results with those of the Nazis. Afterwards, she asked 10 colleagues to identify and separate the results of the Nuremberg defendants. The experts were unable to do so. These days, the Rorschach test is rarely if ever used: most experts believe that its results provoke too biased and varied assessments.

But in 1945 to 1946, Kelley and Gilbert had to make do with the tools of their day. And they worked at the limit of their capacity and enthusiasm.

In the beginning, it seemed as though the two of them had been brought together throught the workings of fate: Kelley, a gifted psychiatrist, polymath, intellectual, Rorschach system expert, had only one drawback – he did not speak German and required the help of an interpreter; Gilbert, an excellent psychologist, was fluent in German but knew very little about tests in the arsenal of psychiatry. They complemented each other perfectly. For both of them, it was a professional challenge to work at the Tribunal, a momentous event of which they were keenly aware. Never before had they had the chance, the desire or the opportunity to examine the personalities of people who had recently ruled the world.

They strongly depended on each other and relied on each other's achievements. However, soon enough they began to differ considerably in their interpretations of their findings. Gilbert was inclined to conclude that the Nuremberg prisoners were “demon-possessed psychopaths”; Kelley believed that “it was likely that many people in certain circumstances would stoop to similar behaviour”. And each interpreted the findings in favour of his own theory.

The partnership between Kelley and Gilbert was by no means serene. When Kelley left Nuremberg, passing the baton to Goldensohn, Gilbert accused him of stealing his records. At the same time, Kelley had already begun negotiations with publishers to publish a book. He wrote to Gilbert asking for interviews and court transcripts and of course was refused: the latter was annoyed that an ex-colleague was clearly trying to purloin the laurels which should belong to the chief confidant of Nazi leaders and possessor of the darkest, most exclusive secrets. Both were simultaneously working on competing books and vying for possession of unique data. Kelley threatened to sue Gilbert if he used Kelley’s test material and Gilbert accused Kelley of falsifying the records.

In any case, both believed they could offer a coherent concept despite a limited sample range, inconclusive tests, strife and no clear standards or definitions. Kelley insisted that “Nazism was a socio-cultural disease… I had at Nuremberg the purest known Nazi-virus cultures — 22 clay flasks as it were — to study. But this kind of thing can be found in any country – at the big tables where important issues are decided.” Gilbert, on the other hand, argued that Nazism was not part of normal human behaviour but was some kind of special, one-of-a-kind psychopathology. According to Kelley, there was darkness rooted in every human being. For Gilbert, the darkness that engulfed the Nazis was unique. There was one thing they agreed on: the horror was that those monsters were people, they were sane, they were normal.

The high-ranking Nazis were normal – all the test results indicated an undeniable level of intelligence and over-the-top ambition. Their ordinary subordinates were also normal – those who executed orders unquestioningly, without thinking, without doubting, without allowing themselves to think or give in to emotion. It was the very banality of evil, the mundane readiness to do it, the quiet routine of incorporating monstrous realities into daily life and daily existence.

The psychiatric commission determined the conclusion on the majority of the defendants at once. None were found to have a pronounced pathological tendency towards violence. They were all obviously sane, intellectually and emotionally fit and their reactions were in the normal range. The only five who caused serious doubt and discussion were Robert Ley, Julius Streicher, Rudolf Hess, Gustav Krupp and Hermann Göring. These were observed for a long time, having been analysed for changes in their condition. However, all of them, excluding Krupp, were eventually found to be sane and fully capable of answering to the court for committing evil.

The delving into the dark abyss did not go smoothly for anyone. Douglas Kelley stopped resisting, surrendered to the “vortex”, and sank beneath the waves in desperate helplessness. Leon Goldensohn floated on the surface for some time, but eventually, he too would sink face down in the water. Gustave Gilbert resisted the current, floundered, swam out and clung to the hard surface but did not make it to land completely, remaining in the surf.

Kelley, Gilbert and Goldensohn could never fathom what had been revealed to them. The ordinariness, the banality, the dull dusty inside of the scariest, most important mystery. There was no mystery - it was a void.

The experts who worked with the “Nuremberg patients” found that Nazi Germany had been suffered not from some psychological disturbance but from nothing more exceptional than political malaise.

The spores of this poisonous culture proved impossible to be eradicated completely - and a specific infection of recognisable anatomy and genesis still flares up here and there to this day, overwhelming humanity with new strains. But at least the immunity of the planet is able to recognise the attack of the “Nazi virus”. This is thanks to Nuremberg where it was first examined under a microscope.

Sources:

Gustave Gilbert, “The Nuremberg Diary”

Aaron Rothstein, “Psychology at Nuremberg”

Jon Kalish, “A Jewish Doctor Who Put Nazis on the Couch”

Douglas Main, “Nazi Criminals Were Given Rorschach Tests at Nuremberg”

Ian Nicholson, “Psychologist of the Nazi Mind”

Caren Chesler, “Rudolf Hess' Tale of Poison, Paranoia and Tragedy”

Katherine Ramsland, “Professional Suicide”

Alexander Zvyagintsev “Doctors Searched for Nazi Virus”