At the Nuremberg Trials, everything was a first - including the debut of international simultaneous interpretation. The new practice of interpretation was invented and introduced at the tribunal - "simultaneous interpretation" was necessary for the new world, which was going to live on without war. Countries and people managed to come to an agreement in every sense: a common space for dialogue was provided by interpreters, who bore perhaps the greatest responsibility and who had never done anything like this before or since. The Soviet interpreters had a particularly difficult time - and they passed the unprecedented test with flying colours.

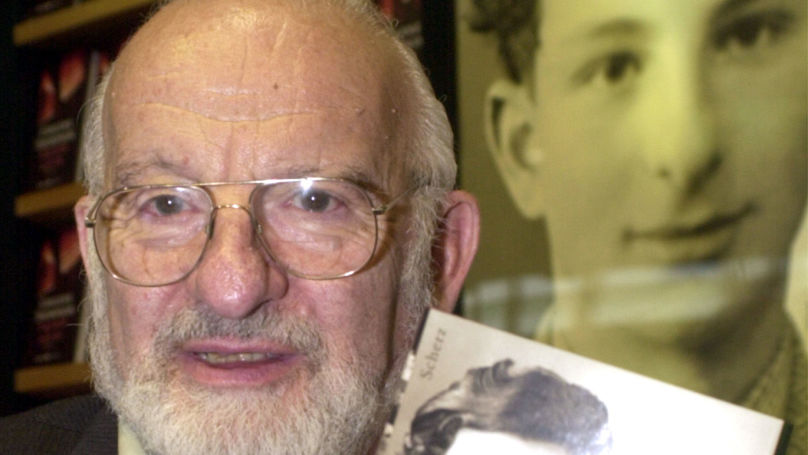

Evgeny Gofman: “I first had to act as an interpreter at Nuremberg in 1946. When I travelled to this ancient city, which at the time had captured the attention of millions of people around the world watching the work of the International Military Tribunal, I had no idea of the tasks I was about to undertake”.

Tatiana Stupnikova: “On a windy, cold evening in January 1946, General Serov, Deputy People’s Commissar of the NKVD, serving under Beria as one of his primary lieutenants, ordered me, an interpreter at the headquarters of the Soviet Military Administration in Germany (SVAG), to come to his office. <...> The audience was brief: ‘I have been informed that you are capable of simultaneous interpretation...’. I was silent, because I had no idea what the term 'simultaneous interpretation' meant. At that time there was only translation and interpretation for me”.

State Department and Linguistics: The Debut of Simultaneous Interpretation

The unconditional surrender of the German armed forces was signed on 7 May 1945 in Reims, France; the Act of Military Surrender in Karlshorst, Berlin, thus effectively ending World War II. That same year, a conference of the four Allied Powers – the USSR, the USA, the UK, and France – was held in London from June 26th to August 8th. It was during this conference that the parties reached an agreement on the Charter of the International Military Tribunal. The Bavarian city of Nuremberg was chosen as the location for the trial of leading Nazi criminals. Aside from being a highly practical decision for a number of reasons, it also was highly symbolic, for it was in Nuremberg that the National Socialist Party held its conventions in the 1930s, thus making Nuremberg the cradle of German fascism. A challenge arose for the organisers: how best to ensure effective interpretation during the sessions of the court to secure understanding among all members of the trial?

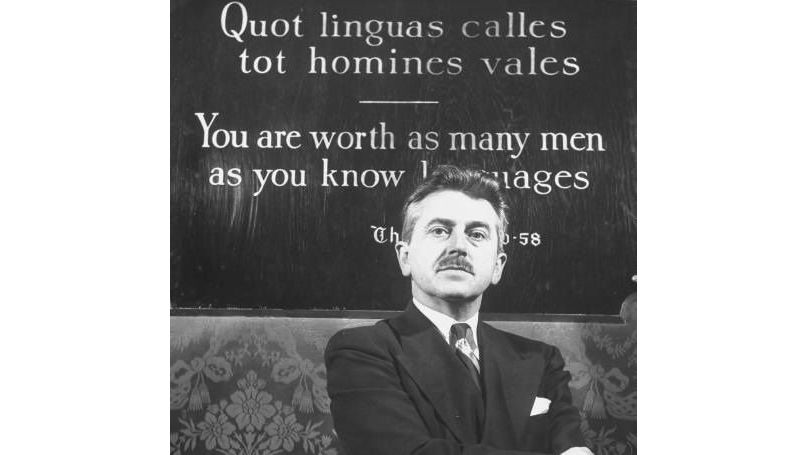

The selection of translators for the US delegation was entrusted to Guillermo Suro, Acting Chief of the State Department's Central Translating Division, but Colonel Léon Dostert, General Eisenhower’s personal interpreter and a member of the US Office of Strategic Services, was actually tasked with finding a solution to this problem upon his appointment as head of the interpreting division of the IMT Secretariat.

Dostert realised that consecutive interpreting, by then widely used in international conferences, would be out of the question in this particular case; it would significantly slow down the trial, already expected to be long because the prosecution had collected extensive evidence to prove the atrocities committed by Nazi leaders against humanity. This was why the colonel suggested using simultaneous interpreting (SI) during the court hearings.

The difficulty of this method of interpretation required the interpreter to render the speaker’s speech into a foreign language at the same time the speech was being delivered. It should be noted that simultaneous interpretation had been used internationally before the Nuremberg Trials, but usually consisted of a simultaneous reading of a pre-translated speech, or a consecutive interpretation performed simultaneously by several interpreters working in different languages.

Dostert and his aides decided that each simultaneous interpreter at the Nuremberg Trials was to interpret the speaker directly into only one other language, thus avoiding a double physical and mental strain. The next step was where to find these people.

Interpreter Selection: From Students to Migrant Aristocrats

Only André Kaminker (the senior interpreter from the French delegation) had some experience interpreting simultaneously. Even the Geneva School of Interpreters founded in 1941, and one of the most respected schools in the field, hadn’t yet graduated simultaneous interpreters. The recruitment process was organised in two stages.

Those who submitted applications were sent to Colonel Dostert for testing at the Pentagon. There, his assistant Uiberall asked them to name 10 trees, 10 car parts, and 10 agricultural tools in their native and foreign languages. The next tasks were more difficult. Their purpose was to reveal abilities in interpretation and translation, knowledge of military and legal terminology, and a high general cultural level. Those who were successful at this stage went to Nuremberg for an interview with Richard Sonnenfeldt, the chief American interpreter at the War Crimes Trial for the US prosecution team. In his memoirs he wrote:

“Whoever [State Department officials] sent them to Nuremberg from the United States did not do a good job. There was much guttural English with heavy German accents and transliteration of German syntax and much German with Hungarian and Polish accents. Early on, a pushy, rotund little man literally danced into my office with hand outstretched, saying, ‘Misster Tzonnefelt, I amm sooo glat to mit you. I speaka de seven linguiches and Englisch dee besst’. ‘Englisch dee besst’ became our pet phrase”.

In late October 1945, Dostert and his team travelled to Germany to supervise the preparations of the IBM translation equipment and to continue the search for interpreters in Europe. Future interpreters were found in Switzerland (mostly graduates of the Geneva School of Interpreters), Belgium, the Netherlands, and other countries whose citizens are usually fluent in several languages. But a month before the start of the trials, the issue of qualified interpreters was not still resolved. The French delegation had promised to have their interpreters in Nuremberg by 7 or 8 November, and Chief Judge Lawrence said the British interpreting team would be in town on 7 November.

Tatiana Stupnikova: "It turned out that the Soviet delegation... arrived at Nuremberg without interpreters, for our leading comrades were convinced that the Americans in the American Zone would take care not only of all the economic and technical problems of the Nuremberg Trials, but also of translation into four languages: English, German, Russian, and French. When it became known that simultaneous interpretation in the courtroom was only allowed in the interpreter's native language and that the translation into Russian from English, German, and French had to be done by Soviet interpreters, this was reported to Moscow and they began a frantic search for interpreters from the other three official languages of the process into Russian. This proved to be quite difficult at the time. That is why the search for interpreters was entrusted to... the NKVD-KGB, which had to carry out the task almost overnight. The perfectly trained officers of... this agency in 24 or (I do not know exactly) even 12 hours completed the task and brought part of the Soviet translators to Nuremberg, just before the opening of the trials. <...> I was in the second group, which arrived in January 1946. However, the haste here wasn’t much lower – it was obvious that there weren't enough interpreters in the first group. And one more thing: I could finally go home in January 1947, not in a month, as the general had promised me”.

Soviet interpreters, who were either sent directly from Red Army Headquarters in Karlshorst or through the All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries (VOKS; Vsesoiuznoe Obshchestvo Kul'turnoi Sviazi s zagranitsei), were educated at Soviet universities. For instance, Evgeny Abramovich Gofman, an interpreter from German into Russian, graduated from the Military Department at the Second Moscow State Pedagogical Institute of Foreign Languages (MGPIIA; Vtoroy Moskovsky Gosudarstvenny Pedagogichesky Institut Inostrannykh Yazykov), and Tatiana Alekseevna Ruzskaya (interpreted from English), Inna Moiseevna Kulakovskaya (interpreted from German) and Konstantin Valerianovich Tsurinov (a simultaneous interpreter, later secretary of the Soviet delegation) – had all graduated from the Moscow Institute of History, Philosophy, and Literature (MIFLI; Moskovsky Institut Istorii, Filosofii i Literatury). However, during the aforementioned selection process, it frequently transpired that a higher degree in linguistics did not always guarantee that a candidate would have real potential for simultaneous interpretation. Along with professional interpreters, talented people from other professions were also recruited to work in the “fishbowl”: teachers, lawyers, career military personnel. Yuri Sergeevich Khlebnikov, a simultaneous interpreter, was a graduate of the HEC business school in Paris (Ecole des Hautes Etudes Commerciales de Paris), and his colleague Peter Uiberall worked as a stockbroker before the war. Many simultaneous interpreters working from Russian came from White Russian émigré families, for instance, Prince George Illarionovich Vassiltchikov, Princess Tatiana Vladimirovna Trubetskaya, who headed the Russian section of the Department, and the aforementioned Yuri Khlebnikov. For many of them, two (or in some cases more) languages were native from childhood.

Patricia van der Elst, who interpreted from French into English during the Nuremberg Trials, recalled how she went through the selection process: “A test was organised at the Geneva University School of Interpreters which, to my surprise, I passed. We had learnt consecutive interpretation only and to find myself speaking into a microphone at the same time that I was listening to a disembodied voice through earphones was thoroughly disconcerting. With the ink of my degree scarcely dry, I set out for Nuremberg. It was my first job and, though I did not know it at the time, also my biggest. I went into it with the innocent enthusiasm of my 21 years, looking forward to the freedom from home, the glamour of a foreign assignment, and the lure of the unknown… When I did reach Nuremberg, I was billeted at the Grand Hotel where I was allowed to remain for the duration. I spent a week in the public gallery listening to the proceedings in the courtroom. Then, after a brief test in the booth during a lunch break, I was told I would be starting in earnest the following day. I felt it was a matter of sink or swim. I swam”.

Another interpreter, Elisabeth Heyward, started working in the booth the day after she arrived at Nuremberg, and successfully passed this “baptism by fire”.

Evgeny Gofman: “The day after we arrived, the Americans leading the team of interpreters gave the new interpreters a test. A German text was read into the microphone from the courtroom and had to be translated into the other working languages (Russian, French, and English). The test went well and the next day I was sitting in the booth next to my colleagues. The presiding officer gave the floor to the German counsel representing the defendant, Grand Admiral Raeder. A rain of legal interpretations of the various laws, formulated in the most complicated syntactic periods, rained down on me. With great difficulty I waded through this thicket, trying to grasp the slightest glimmer of common sense... When I emerged from the booth, my mind was full of fog”.

Furthermore, not all simultaneous interpreters were involved solely in interpretation and translation work. For example, Richard Sonnenfeldt, a senior interpreter with the American delegation, also acted as assistant to their chief investigator; Oleg Alexandrovich Troyanovsky (son of Alexander Antonovich Troyanovsky, the first Soviet ambassador to the USA) and Enver Nazimovich Mamedov were only nominally interpreters, although they did frequently help their colleagues in the “fishbowl”. Both were diplomats: Troyanovsky worked as secretary to the Soviet judge Iona Timofeevich Nikitchenko, while Mamedov was tasked with secretly bringing General Paulus, captured during the Battle of Stalingrad, to Nuremberg to testify at the trial.

Yet, not all of the candidates had a short journey to the “fishbowl”. Many started out in the translation service and were transferred to the simultaneous interpreter team only after some time (ranging from one week to several months). Occasionally, the opposite happened as well. Some simultaneous interpreters, victims of Nazi concentration camps or children of such victims, could not bear the immense psychological strain and transferred to the translation service. For example, one young graduate of the Geneva School, Jewish by birth, who had shown amazing potential for simultaneous interpreting during the selection process, froze and was unable to utter a single word when she found herself in the booth during the trial. She later said to the senior interpreter that she was simply unable to work, seeing before her the people responsible for the death of so many members of her family:

“These people murdered twelve of the fourteen members of my family”.

The interpreters’ salaries varied from one delegation to another. Interpreters working for the American delegation had the highest salaries; those working for other delegations were paid considerably less. The American delegation also employed the most interpreters and translators, at least 640 people, while the Soviet delegation, for example, only had 40.

Life in a ‘Fishbowl’

The simultaneous interpreters worked in the “fishbowl”. Why the name? The booths were surrounded on three sides by low glass panels. The top remained open; in other words, there was absolutely no question of any kind of soundproofing, now one of the mandatory working conditions for simultaneous interpretation. The “fishbowl” was located at the back of the hall next to the defendants' dock and consisted of four three-person booths (English, Russian, German, and French). The booths could sit three interpreters at a time, and provided three sets of earphones and one hand microphone.

Earphones were also provided for everyone in the courtroom itself, thus enabling participants to listen to the original speech as well as its interpretation into any of the official languages. The system had five channels: the first channel transmitted the original speech, the second was reserved for English, the third for Russian, the fourth for French, and the fifth for German. The interpreters’ headphones were set only on the original (channel one). There were six microphones in the courtroom: one for each judge, one on the witness stand, and one on the prosecutor’s podium.

The American firm IBM offered to equip the Nuremberg Palace of Justice courtroom with state-of-the-art equipment – the modernised IBM “Hushaphone Filene-Finlay system” – at no charge, with the US government only paying for shipment to Nuremberg and installation in the courtroom.

The International Military Tribunal’s first session began at the Nuremberg Palace of Justice on 20 November 1945 in Courtroom 600.

Thus, that day may be considered the official birthday of simultaneous conference interpreting in its current meaning.

By 9:30 a.m. local time, members of the prosecution teams and the defence counsel had taken their places, and the 12 interpreters sat ready in the “fishbowl”. At 9:45 American Military Police escorted 20 defendants into the courtroom, and the great hall fell silent. The defendants then took their seats on two rows of benches. At 10:00 the court secretary called the room to order: “Order! Please stand! The court is in session!” The judges took their seats on the high bench, and the session was declared open. The machine of justice was set in motion, and the interpreters were, needless to say, one of the main forces driving it forward. The task ahead of them, and the responsibility it entailed, were truly colossal. Extreme physical and emotional concentration would be required, which was why the interpreters had to follow a strict working schedule designed by Colonel Dostert and his aides from day one.

The interpretation and translation department was split into five groups:

1. Simultaneous interpreters (36 people).

2. Auxiliary consecutive interpreters (12 interpreters with languages other than the four official languages used during the proceedings).

3. Translators (8 sections with 20-25 people per section; 15-18 translators would prepare “raw” translations, with the remaining 8 later editing and proofreading the translated material; each team was allocated 10 typists).

4. Shorthand reporters (12 people for every working language).

5. Shorthand editors (more than 100 translators were tasked with editing shorthand notes by comparing them to the recordings of the proceedings).

The number of simultaneous interpreters remained constant throughout the trial. Three teams – A, B, and C (12 interpreters per team) – worked in shifts. Their typical workday would look something like this: Team A would work for 85 minutes in the “fishbowl” in the morning. There were three interpreters per booth, each with an allocated source language, from which they were meant to be interpreting into the language of the booth. While one interpreter was working, the other two waited for their turn. Whenever there was a change in a speaker or source language, the interpreter would pass the microphone to the colleague who worked with that particular language.

During this time, the interpreters from Team B sat in neighbouring Room 606 and followed the proceedings through headphones. They were on standby ready to replace one or more of their colleagues in the courtroom if, for whatever reason, their colleagues were unable to continue interpreting or made serious mistakes in their interpretation. Furthermore, interpreters from Team B made their own glossaries, based on the simultaneous interpretation of their colleagues from Team A. This ensured that all the teams used the same terminology, and provided continuity in the interpretation.

A large number of documents presented during the trial as evidence for the prosecution were in German. Translators prepared translations of these documents so that the interpreters would have visual materials to help them while working with various statistical data, full of figures and proper names. However, because of the immense workload, translators did not always have the time to translate all the documents. In this case, the interpreters would receive the documents in their original language for sight translation.

After the first 85 minutes were up, the teams would swap places: Team A would go to Room 606, and Team B would take its place in the “fishbowl”. At 1:00 p.m. the presiding judge would announce an hour-long break, after which the two teams resumed working according to the same schedule. This would be a rest day for Team C. At a later stage, the third, resting, team would check the verbatim reports, help their translator colleagues on the documents and interpret at closed IMT sessions.

The team’s head interpreter sat between the English booth and the officers of the court, and was tasked with ensuring that the equipment worked well, and that the interpretation was of good quality. Furthermore, he was the go-between for the judges and the interpreters in the booths. He operated a control switch that would flash a yellow or red light. The yellow light was used to notify the presiding judge that the speaker was speaking too quickly, or to ask the speaker to stop and repeat what he had just said (the optimal speed for SI was 60 words per minute), and the red light was used to inform the judges of a serious issue, such as one of the interpreters suffering from a coughing fit, or equipment failure.

On average, every team would spend three hours a day, four days a week, working in the “fishbowl”: the court was in session every day except Sunday, from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m., with a one-hour break for lunch. This rotation ensured the most effective results and remained unchanged even after 18 April 1946, when Colonel Léon Dostert was replaced as the Head of the Interpretation and Translation Department by US Navy Lieutenant Commander Alfred Steer.

Simultaneous Interpretation of Emotions

Most of the interpreters at the Nuremberg Trials were under 30 years old, and the youngest was a young woman of just 18.

Some fifty years later, Patricia van der Elst would say, “Looking back, I am amazed how well we coped and how quickly we acquired the new skills”. In one of her interviews, Tatiana Ruzskaya remarked, “It was probably only our youth that helped us endure such terrible stress…”; Marie-France Skuncke, also an interpreter at the trial, said “the quality of interpreting improved along the way”.

In her book, “Nothing but the Truth”, Tatiana Stupnikova remembered an interesting story that happened when she was working in the “fishbowl” interpreting Sauckel, who became very emotional and started shouting, trying to convince the judge of his innocence. “We were interpreting all of this, quickly and accurately, and the interpretation flowed smoothly to the headphones of Russian listeners in the courtroom. And then something inexplicable happened to us. When my colleague and I came back to our senses, we realised to our utmost horror that we had leapt from our chairs and, standing in the interpreters’ ‘fishbowl’, were engaged in an angry fighting match, just like the prosecutor and the defendant in the courtroom in front of us. What is more, I felt a sharp pain in my upper arm, just above the elbow, and, when I turned to look at my colleague, I saw that he was gripping my arm and telling me, just as loudly as the prosecutor, but in Russian, ‘You should be hanged!’ And I, crying from the pain in my arm, was shouting back at him, ‘Don’t hang me! I’m a worker! I’m a sailor!’ All those present in the courtroom turned to look at us. “I don’t know how this might have ended, if it were not for Judge Lawrence who looked at us in a kindly manner that reminded me of Mr Pickwick. He said very calmly and with no hesitation, ‘Something seems to be the matter with the Russian interpreters. This session is now adjourned’”.

Obscenities

Some interpreters refused to translate what they considered to be obscene, or tried to soften them. For instance, one witness for the defence spoke of the conditions created for prisoners in a labour camp, which allegedly had a library, a swimming pool, and a brothel. A young American interpreter, who was translating this witness’ testimony into English, stuttered and fell silent at the last word. The President of the Court Judge Lawrence intervened with the question: “So what did they have there?” At that moment, the male voice of the head of the interpreter shift echoed, “Brothel, Your Honour!” There were also times when the interpreters picked up euphemisms. During the translation of the testimony of a concentration camp guard, the words "Jews could be pissed on" were translated by the interpreter as "Jews could be ignored". In both cases, the interpreters were replaced because, according to Alfred Steer, they were seriously distorting the testimony.

Of course, given the immense psychological stress, the interpreters would occasionally make mistakes, despite their considerable concentration. For instance, one young Soviet interpreter, when interpreting Göring, failed to understand the meaning of the phrase “Trojan horse politics”. She paused, lost the thread of thought, and was unable to continue, forcing the presiding judge to stop the session

Tatiana Stupnikova: “... one also had to sit in the simultaneous interpretation booth and had to convey with the utmost accuracy the meaning of every speech, every lightning remark and comment, in my case – the German-speaking participants in the dialogue, while remaining calm and not giving away his feelings and attitude to what was happening... That's when you will understand the psychological difficulties of someone who was unexpectedly involved in an event such as the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. <...> The former minister [Speer] confessed he was well aware that workers had been sent to Germany from Europe against their will. But it was always his task to ensure that there were as many of these forced migrants in Germany as possible. I confess that translating these words was difficult for me. The defendant said, ‘As many as possible!’ and I was already preparing in my mind to say, ‘As few as possible!’ Either I must not believe my own eyes telling me that the man in front of me is the image of God, or I misheard this monstrous phrase: ‘Yes, they are being forced, but let them be brought in as many as possible!’”

Defendants often began their answers with the word “Ja”, which can be literally translated as a confession of guilt. The prosecutor would ask, for example, "Were you aware at the time that your actions were criminal in nature?" to which the accused would reply, “Ja...”. But in this case, “Ja” was a filler for the pause the defendant needed to think. Peter Uiberall instructed the interpreters to pay particular attention to this German word and not to translate it as a positive answer until one is absolutely certain that the defendant actually agrees with the prosecutor's statement,

“...otherwise one might be found guilty of something he had not done and hanged. For as soon as the word 'yes' is recorded in the report, the person who said it is doomed”.

And how did the defendants feel about the interpreters? Some, like Göring and Rosenberg, often criticised them. Others, on the contrary, had great respect for the work of the interpreters and sought to help them. Before the trial, during conversations with the American military psychiatrist Leon Goldensohn, defendant Hans Frank would address Goldensohn's interpreter Trieste as “Herr Interpreter”. Albert Speer wrote in his memoirs: “In the courtroom, however, we encountered only hostile faces, icy dogmas. The only exception was the interpreters’ booth. From there I might expect a friendly nod”. One of the defendants, Hans Fritzsche, even made a list of linguistic recommendations for his fellow defendants to make the interpreters’ work easier. For example, he advised that sentences be constructed so that the semantic verb was closer to the beginning of the sentence, which greatly facilitated the work of the interpreters. On other occasions, the defendants, for instance, Schacht and Speer, would try to work together with the interpreters in the “fishbowl”, suggesting German equivalents for some foreign words.

Firsthand: ‘Triumph, Albeit Small’

In his book, “The Nuremberg Epilogue”, Arkady Poltorak, then the secretary of the Soviet delegation at the International Military Tribunal, paid particular tribute to the Soviet translators:

“There were four glass booths next to the dock. They each seated three interpreters. Each team interpreted from three working languages into their native language, the fourth. Accordingly, the translation staff of the Soviet delegation consisted of specialists in English, French, and German, all of whom together translated into Russian. For example, one of the defenders is speaking (in German, of course) – the microphone passes to Zhenya Gofman. The president suddenly interrupts the lawyer with a question. Zhenya hands the microphone to Tania Ruzskaya. Lord Lawrence's question is translated. The defence counsel's answer must now follow and the microphone goes back to Gofman…

But the work of our ‘translation corps’ was not limited to this. The transcript of the translation had to be carefully edited and compared with the tape recordings, where Russian speech was interspersed with English, French, and German. Furthermore, a large number of German, English, and French documents were to be translated daily for the Soviet delegation.

Yes, there was a lot to do, and I thanked fate that our interpreters were not only qualified (most of them had special language education), but, just as importantly, young and physically strong. This helped them to withstand such a considerable workload. Today, as I write these lines, I very much want to say kind words to Nelly Topuridze and Tamara Nazarova, Seryozha Dorofeev and Masha Soboleva, Lisa Stenina and Tanya Stupnikova, Valya Valitskaya, and Lena Voytova. Their diligent and skilled work was a major part of the success of the Nuremberg Trials. Many Soviet historians and economists, philosophers, and lawyers owe a great debt to them, who have the opportunity to use the rich archives of the Nuremberg Trials in their mother tongue. (...) I cannot help but mention here Tamara Solovieva and Inna Kulakovskaya, Kostya Tsurinov, and Tanya Ruzskaya. After graduating from the Moscow Institute of History, Philosophy and Literature, each of them worked for several years in the All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries. And we were proud to realise how much higher they were in their education compared to translators from other countries. When the finally corrected transcript was signed by Kulakovskaya or Solovieva, one could hope that a future historian studying the Nuremberg Archive would not find cause for complaint. Moreover, with their experience of dealing with foreign cultural figures, these comrades helped the Soviet delegation to find common ground with their American, English, and French colleagues.

We had far fewer translators than the other countries' delegations. And here we all had a chance to see for ourselves what the new Soviet attitude to work was all about. Prince Vassiltchikov, who was in the service of the Americans, was perplexed when he asked our interpreters:

– Dear ladies and gentlemen, why are you still translating documents? It is not like you are getting paid for it.

The simultaneous interpreters, who spent a great deal of energy on their direct duties, were indeed relieved of any other translation. However, Kostya Tsurinov and Tamara Solovieva, Inna Kulakovskaya, and Tanya Ruzskaya could not remain indifferent when their fellow ‘documentarians’ Tamara Nazarova or Lena Voytova were bending under the weight of their workload.

We had an unwritten rule - camaraderie - evident in other ways as well. As I said earlier, there were always three people sitting in the interpreter booths of each country. The speeches of the court speakers sometimes lasted for an hour or more. In these cases, the interpreter from the respective language worked with maximum intensity, while the other two could listen, so to say, half-heartedly, just not to miss a line in ‘their’ language. The American, English, and French interpreters would usually read an entertaining book or just rest in such a situation. Our fellow translators almost always listened to the speaker together and helped the interpreter to the best of their ability.

Even the most experienced interpreter is bound to lag behind the speaker when providing simultaneous interpretation. Translating the end of a phrase that has just been spoken, the interpreter is already listening and memorising the beginning of the next one. If a speech contains a long list of names, titles, numbers, this creates additional challenges. And this is where our interpreters always had their shift mates to help. They would usually write down all names and numbers on a piece of paper in front of the person doing the interpretation, and the person would read the notes without straining their memory too much when they got to the right place. This not only prevented mistakes, but also ensured that the translation was fully coherent.

To be fair, this form of camaraderie soon spread amongst the interpreters of other delegations as well. This is the triumph, albeit small, of our morality!”

By Elena Kalashnikova