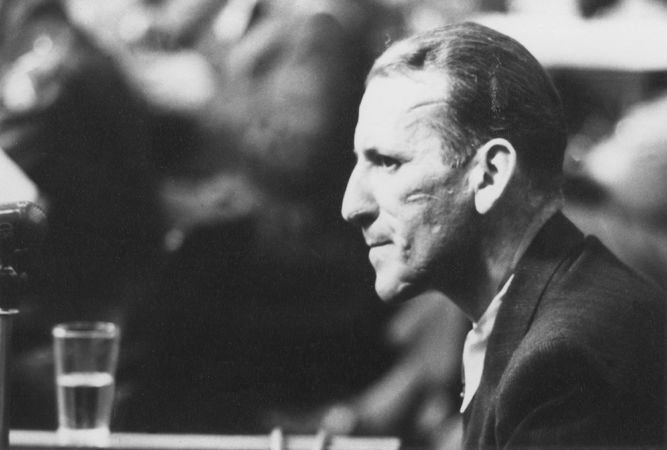

On 10 December, Ernst Kaltenbrunner first appeared in the Nuremberg trials courtroom. Doctors got him back on his feet after a series of seizures. The defendant, Kaltenbrunner, was to stand trial not only for his crimes, but also for the actions of the most intricate part of the Reich's bureaucratic system – the RSHA (Reich Main Security Office). Peter Romanov provides his view on this man and the organisation he headed.

RSHA Führer: Third, After Heydrich and Himmler

Historically, since the time of the first chief of the RSHA, Reinhard Heydrich, (one of the authors of the idea for the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question”, who was killed by Czech patriots in 1942 in a British special operation), the chief of the security office would try to take over many of the powers and functions of other older German agencies, like the Abwehr or police, but at the same time diligently avoid assuming formal responsibility. The rationale made sense: one could attribute success to oneself and place responsibility for failures on others – either on someone else's agency or, at the very least, on one's own subordinates. This tradition was continued by Heydrich’s successor, Heinrich Himmler, and then by the third and final chief of the RSHA, Ernst Kaltenbrunner.

The RSHA Amt IV, or Gestapo, headed by SS Gruppenführer Heinrich Müller, was a typical example of how the system worked. It was the de facto main punitive service with the right to arrest a person without charge. The Gestapo could easily arrest anyone, as the courts were prohibited from interfering with the decisions of the service. At the same time, the head of the RSHA – Heydrich, Himmler, and Kaltenbrunner – had every right to make a personal decision. But, upon taking office, all the chiefs chose to immediately transfer the right of signature to the director of Gestapo, namely Müller.

However, even Müller could not issue an order to execute a prisoner. By law, the Gestapo had no right to execute. Nevertheless, people often died under torture, and even more often, the agency killed prisoners by hands of the employees of another institution – the concentration camps. Death was legalised in their domain.

Lawyers at the Nuremberg trials repeatedly tried to exploit this legal uncertainty. The clearly guilty defendants sought to shift the responsibility to another service or other executors. Later on, when Adolf Eichmann was tried in Israel, he could also claim that he did not kill a single Jew, since, although being responsible for the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question”, he merely sent trains of victims to concentration camps.

Hierarchical ambiguity was characteristic of the intelligence and counterintelligence services too, which were also part of the RSHA. However, there was one catch. Müller and Walter Schellenberg, head of RSHA Amt VI, treated Kaltenbrunner with contempt, considering him to be intellectually inferior to them, and therefore often communicated directly, bypassing the chief.

Scar-faced Nazi

It is difficult to say how right they were. Numerous studies by psychologists who worked with the defendants showed that almost all of them, including Kaltenbrunner, had fairly high IQ scores. Kaltenbrunner did have a Juris Doctor degree, after all. He obtained the degree before the Nazis came to power – in 1926 in Austria, where he hailed from.

And his ancestors were hardly fools. His great-grandfather, Carl Adam Kaltenbrunner, was an official in the Austrian Audit Chamber and a poet; his grandfather, Karl Kaltenbrunner, served as burgomaster of Eferding for over 20 years. His father had a good legal practice. Ernst graduated from the Faculty of Chemistry at the Graz University of Technology, then the Faculty of Law at Graz University. He moved to Linz, opened a law office, and got married. And he had passion for the ideas of National Socialism. In October 1930, Kaltenbrunner joined the Austrian NSDAP, and in August 1931, he became a member of the SS.

Many were misled, and some say Himmler was afraid of Kaltenbrunner's appearance because it resembled that of a street thug. He was two metres tall, his face was rough, as if carved with an axe, and his cheeks were scarred. According to one story, he injured his face in a car accident. The other is more romantic. In his youth, like many European students, Ernst was fond of so-called “Mensur fencing” (team duels where sides fight in static rows and the fighters have no protection for the lower parts of their face). Sword scars were seen as a badge of honour.

“Kaltenbrunner was a giant in stature, heavy in his movements—a real lumberjack. It was his square, heavy chin which expressed the character of the man. The thick neck, forming a straight line with the back of his head, increased the impression of rough-hewn coarseness. His small, penetrating, brown eyes were unpleasant; they looked at one fixedly, like the eyes of a viper seeking to petrify its prey”.

The Labyrinth: Memoirs of Walter Schellenberg, Hitler's Chief of Counterintelligence

According to eyewitnesses, Kaltenbrunner drank from dawn to dusk, blending cognac and champagne, and smoked up to a hundred cigarettes a day. So the face of a street thug was complemented by his tobacco-stained teeth and yellowed fingers. They say that Kaltenbrunner could easily bend a horseshoe. He must have inherited his physical strength from his father's distant ancestors, who were smiths.

Austrian Stepping Stone

The fact that the RSHA chief was from Austria helped him make his career. After all, Adolf Hitler was also Austrian. The Anschluss of Austria saw massive support from the population. Austrians holding senior positions in the Reich became commonplace. Almost a million Austrians fought for the German Reich during World War II, and they were actively involved in “solving the Jewish question” in the concentration camps.

According to the standards of the Third Reich, Kaltenbrunner's past was remarkable. Even before the Anschluss, he had been secretly transporting money from Bavaria to Austrian National Socialists. In 1934, he was arrested and detained. In May 1935, he was arrested again for six months. For these arrests, he was subsequently awarded the “Blutorden” (the Blood Order), an honorary NSDAP party decoration. He was one of the leaders of the 1934 coup in Vienna, when the SS, disguised as Austrian soldiers, killed Austria’s Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuss.

In March 1938, right after the Anschluss, Kaltenbrunner was appointed state secretary of public security in the office of Hitler's governor, Arthur Seyss-Inquart. Welcoming Himmler to Austria at the airfield, Kaltenbrunner reported to him: “The SS is in formation and awaiting further orders”. Since then, he held senior positions in the SS apparatus in Austria – first as SS-Brigadeführer, then as SS-Gruppenführer. In June 1940, Kaltenbrunner was appointed High SS and police leader for Donau, which was the primary SS command in Austria. He also established the largest intelligence network in Austria. And in 1943, he was invited to Berlin.

Chief Supervisor of Mauthausen

Technically, the RSHA chief was not responsible for the concentration camps. But as an exception, Mauthausen, the largest Austrian concentration camp, was left under the supervision of Kaltenbrunner – who else but an Austrian should keep an eye on how things are going at home. As a matter of fact, it was not just a single concentration camp, but a whole system consisting of a central camp and 49 branches scattered throughout Austria. Mauthausen had its own specialisation – intellectuals from countries occupied by Germany were usually sent there.

Kaltenbrunner closely monitored this extensive killing industry. He even visited the camp, where he was shown different methods of killing: shooting, hanging, and gassing. During his interrogation in Nuremberg, Kaltenbrunner persistently denied this fact, even though his “business trips” to Mauthausen were documented in a newsreel.

Then again, Kaltenbrunner denied everything during the process. For example, he claimed that Himmler had misled him on the “Jewish question”. However, it was proven that he was present at a conference together with Hitler, Goebbels, Himmler, and Heydrich in December 1940, where it was decided to send all Jews unable to do heavy physical work to gas chambers.

Not to mention the fact that since the time of Heydrich, there had been political departments in the commandant's office of each camp, directly subordinate to the RSHA. The head of the RSHA regularly received reports on the execution of prisoners. As noted by historian Konstantin Zalessky, the Third Reich created such a “cynical system that the Jewish question is handled by the RSHA, but allegedly it has nothing to do with the extermination of Jews”.

Kaltenbrunner said at the trial that all decrees and legal documents that bore his signature had been "rubber-stamped" and filed by his adjutant. And Gestapo chief Heinrich Müller had allegedly signed a lot of documents of which the head of the Reich Main Security Office was not aware.

On rare occasions, something did escape Kaltenbrunner's attention. Sometimes he would hand a case over to his subordinates right from the start. Moreover, the chief of the RSHA was entrusted with many additional functions. Few people know, but it was Kaltenbrunner who replaced Heydrich as president of the International Criminal Police Commission (ICPC), the very organisation now known as Interpol. (It should be clarified that during “German rule”, the organisation, established in 1923, actually did not function, and was revived in 1946). Finally, there were instances where his subordinates acted on direct orders from Himmler without informing their boss. Himmler, especially towards the end of the war, was playing his own game. Himmler was hoping for a separate peace with the Allies and did not want his steps to be known to Bormann and Hitler, whereas Kaltenbrunner was guided by them.

But overall, the head of the RSHA was not merely a figurehead of the Reich system. Therefore, he was justifiably put on the bench of Nuremberg defendants. Kaltenbrunner participated jointly with others in the development of a whole series of well-known intelligence operations. He was responsible for the notorious Operation Long Jump, a plot to assassinate the “Big Three” – Stalin, Churchill, and Roosevelt – at the Tehran Conference of 1943. Kaltenbrunner introduced Hitler to Austrian-born German Otto Skorzeny, a special unit operative who organised many covert operations.

According to witness statements, after the failure of the Wehrmacht at Stalingrad, Kaltenbrunner had no doubt that the war in the East had been lost. However, he was blindly loyal to the Führer and therefore remained with him almost to the end. It was only at the very last moment that Kaltenbrunner fled to the Alps, climbing as high as he could, but even there he failed to escape the American special forces.

‘Freedom’ Behind Barbed Wire

American biographer Frank Brady described an episode in his book “Endgame: Bobby Fischer's Remarkable Rise and Fall - from America's Brightest Prodigy to the Edge of Madness”. The famous chess player Bobby Fischer was anti-Semitic and considered the Holocaust to be a fiction. When Fischer found out that Kaltenbrunner's son was living in Vienna, he went to his house. He was interested in asking if the story about the concentration camps was true and had not been inflated on purpose. According to the author of the book, the meeting was a great disappointment for Fischer, because the son of his idol, Kaltenbrunner, was a “staunch liberal”.

But the son of the RSHA head showed something curious to the chess player. It was a letter from Kaltenbrunner to his family, which he wrote in Nuremberg prison. As it turned out, Kaltenbrunner called himself a man of considerable faith:

“My fate is in God's hands. I am glad that I never turned away from him”. Also, he was a “freedom fighter”: “Was it not my duty to open the door to socialism and freedom?”

The Lord will deal with the faith of the RSHA chief without our help. There is something more interesting than that. Of course, socialism is different; Kaltenbrunner was talking about “National Socialism”.

This is somewhat clear. But only roughly, because there is a considerable difference between the original roots of National Socialism, from which the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) grew up, and the ideas of fascism itself, which fuelled Hitler's Reich. But we know very well what kind of “freedom” the supervisor of the Mauthausen concentration camp had “opened the door” to.