Dmitry Astashkin, Candidate of Historical Sciences (PhD) and Senior Researcher at the Saint Petersburg Institute for History of the Russian Academy of Sciences, explains the decisions that were promptly made by the Soviet prosecution team at the Nuremberg trials.

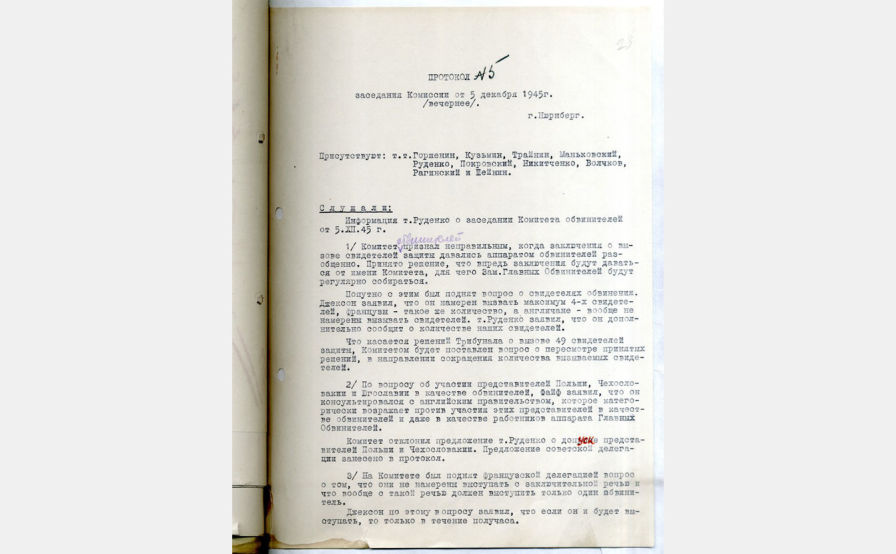

The document reveals the logic behind each country's decision to reduce the number of witnesses. US prosecutor Robert Jackson was the first to reduce their list of witnesses. According to his strategy (of “proving incredible events using credible evidence”), the prosecution should have relied on quoting seized Nazi documents, rather than on witnesses who could potentially be unreliable. In line with Jackson's decision, the Soviet side also shortened its list of witnesses for the Soviet prosecution, prepared on 27 November.

The selection of witnesses to appear before the court was based on the nature of the charges – testimonies had to cover different types of crimes and the different biographies of the witnesses – including those reflecting different strata of Soviet society. For example, in February 1946, five Soviet citizens testified at the Nuremberg trials about crimes in the occupied territory of the USSR: Jacob Grigoriev, a collective farmer, spoke about the destruction of villages in Pskov; Nikolai Lomakin, a Russian Orthodox priest – about the Siege of Leningrad and the destruction of churches; Doctor Eugene Kivelisha – about the inhumane conditions in camps for Soviet prisoners of war; Joseph Orbeli, a Soviet orientalist, historian, and academician – about the devastations in besieged Leningrad; and Abraham Sutzkever, a Jewish poet and partisan, testified about the Holocaust in Vilnius, Lithuania.

It turned out that the extensive reading out loud of the documents made the process unspectacular. In 1946, The New Yorker described the situation, saying “the courtroom was a citadel of boredom”. But this method proved to be quite convincing on the legal side, as the documents contained important facts.

By Ekaterina Chernetskaya