They took up the posts one after another, and they were similar in age, origin, and education. This is where the similarities end and the “struggle of opposites” – political, professional, stylistic, and even epochal – begins.

Traveller vs. Home-lover

They were both born at the turn of the century: Maxwell Fyfe in 1900, Shawcross in 1902. The former's father was a university professor and the latter's one was a headmaster of a gymnasium. Neither of them was rich, but thanks to their families, they were quite intelligent and aimed at work from a young age. But one embodied the British heritage; he held positions that had survived from the Middle Ages and strictly followed Victorian morality. Meanwhile, the other proved to be a true son of the 20th century, a century of mobility, experimentation, and freethinking.

David Maxwell Fyfe took up the legal path in his youth and never left it, as he followed it step by step to the top of his professional career. He was born in Britain, served Britain, and did not live anywhere but Britain.

Hartley Shawcross was born in Germany. At the age of 16, he went to Switzerland to learn French and to become a doctor. He did not become a doctor, but he learned French so quickly and so well that in 1920, he took the risk of offering his services as an interpreter to a British delegation that arrived at the Geneva Congress of the International. Perhaps it was from his fellow delegates that he got caught up in socialist ideas. His older colleagues advised the talented young man to leave medicine and devote himself to a political career. And the best profession for a politician is to be a lawyer.

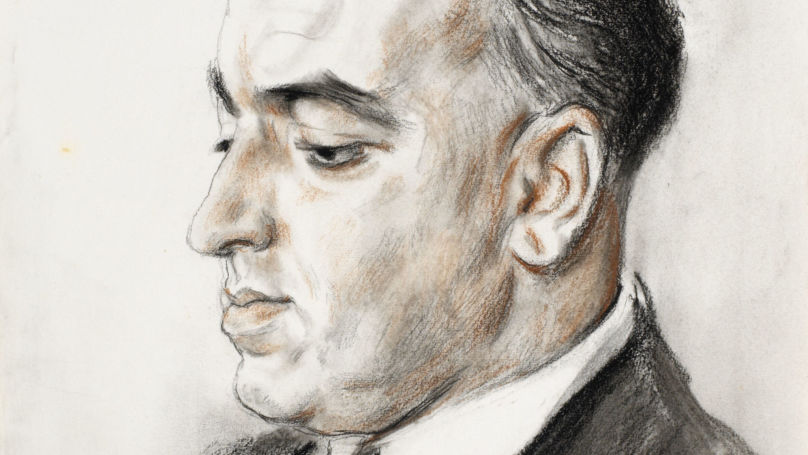

Shawcross returned to England, studied law, started an internship in Liverpool, but soon moved to the capital. By the late 1920s, he had become a Labour Party activist, a member of parliament, and a rising star of the bar. Shawcross was also a handsome man from his youth to his old age.

Shawcross gained fame in his first case in a London court. His client had sold a talking parrot which, having changed its owner, did not utter a word. The chagrined buyer decided that he had been deceived and demanded his money back. But Hartley Shawcross, a 25-year-old lawyer, got the bird “to talk” right in court, amusing the court, the public and the seller of the parrot. He won the case.

Presenter vs. Interrogator

Alas, the public and participants at the Nuremberg Tribunal could not appreciate the talent of Shawcross as an interrogator. They witnessed the meticulous and pedantic David Maxwell Fyfe. According to his contemporaries, he was a little tedious. But he was the one who drew the most confessions out of witnesses and defendants.

A stern Scotsman “with a Middle Eastern look”, as his contemporaries described him, David Maxwell Fyfe made a professional choice as a young man: politics plus law. He did not hang around Europe, but served in the army during both World Wars. Socialist and Labour ideas did not interest him – Maxwell Fyfe was a consistent Tory.

He worked his way up the career ladder, little known to the general public but valued by the conservative government. In 1942, Winston Churchill appointed him as solicitor general (a high prosecutor position), and in May 1945, he was appointed attorney general.

Incidentally, Maxwell Fyfe, like his patron Winston Churchill, opposed the idea of trying Nazi criminals at an international court. Both were the kind of people who would have preferred to shoot the Nazi leadership without further ado.

Maxwell Fyfe gratefully accepted knighthood, he was knighted ex officio. But he did not hold on to it for long: the Tories lost the election to the Labour Party, and just before the Nuremberg trial, the post of the attorney general was taken by... Hartley Shawcross. He, as a true Labour and socialist sympathiser, tried to renounce the title, but his fellow party members did not allow it.

At the Nuremberg trials, Shawcross was remembered for two episodes. The first one was a brilliant opening speech on behalf of the British prosecution. Commentators referred to it as a sharp rapier, while speeches by the US and Soviet prosecutors, Robert Jackson and Roman Rudenko, were compared to a heavy mace. The second episode was the final speech. It was notable for being emotional and artistic.

The period between the two speeches – basically the entire Nuremberg Trials – Hartley Shawcross, while formally remaining lead British prosecutor, spent in London. The Attorney General's Office wouldn't let him get distracted by Nuremberg. For the eyewitnesses of the tribunal, David Maxwell Fyfe was the British prosecution.

Money-Bag vs. Church Mouse

The Nuremberg trials, the second half of the 1940s, was the time of the peak of Hartley Shawcross’ career. But the 1950s saw the Labour Party enter a decade of defeats. Sir Hartley Shawcross lost his office, and he seems to have been disillusioned with politics. In 1958, he left the bar and refused party membership. As a life peer, he only attended meetings of the House of Lords.

Now his area of interest was the media and business. Shawcross became a board member of several major companies, and fought against censorship. By 1985, he had served as the chancellor of the University of Sussex for 20 years.

But for his colleague and rival David Maxwell Fife, Nuremberg was just a stepping stone; he went further. The Conservatives won: Sir David got the position of home secretary, and in 1954, he was appointed Lord Chancellor. This is one of the highest-ranking public offices in the United Kingdom. However, nowadays it has had to be adapted to new realities, and today the Lord Chancellor acts as secretary of state for justice.

David Maxwell Fife was a true conservative. He opposed the abolition of the death penalty and fought particularly hard against homosexuality. During his years of tenure as secretary of state for justice, thousands of gender non-conforming men were imprisoned.

Sir David passed away in early 1967. He was married to a single woman all his life and had three daughters, so no one inherited his title of viscount. His financial assets at the time of his death were just over £20,000.

Hartley Shawcross long outlived his deputy at the Nuremberg trials. The latter had long been lying in a coffin while Sir Hartley still had his third marriage, wealth, travels, and the 21st century ahead of him.

In early youth, he married a seriously ill girl. Out of great love. The marriage was doomed to have no children, his wife was constantly ill. In 1943, she was tired of fighting and took her own life. A few years later, Shawcross married again and the couple had three children. But in 1974, a new tragedy happened; the politician's wife died as a result of an unlucky fall from a horse.

Nearly a quarter of a century later, the 95-year-old Shawcross got married for the third time to his long-time girlfriend. The shocked heirs would demand the dissolution of the marriage on the pretext that their father was allegedly a legally incapable person. There would be legal proceedings, the press would intervene. The children of Shawcross would have a legal victory in England. The couple would then leave for Gibraltar, and the local court would recognise their marriage.

Hartley Shawcross passed away in 2003 at the age of 101 with sound mind and memory. “I feel like I have lived a happy life. Not a very useful, but a happy one”, he once said.

by Julia Ignatieva