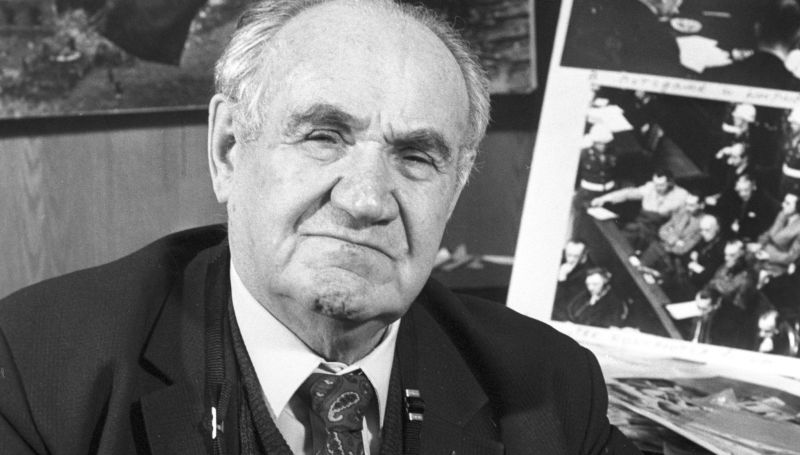

Yevgeny Khaldei – author of unique photographs of the Nuremberg Trials and the only Soviet photographer who captured the Great Patriotic War from the first to the last day.

Yevgeny Khaldei went through the entire war, captured the liberation of Europe, the surrender of Germany, the Potsdam Conference, the Nuremberg trials, and the first Cannes Film Festival. He was included in the list of authors of the "100 Most Influential Photos Ever Taken" by Time Magazine.

How did it come to be that Marshal Zhukov's favourite photographer was left with no steady job for 10 years, was not awarded a single solo exhibition in Moscow during his lifetime, and he gained international recognition only shortly before his death in 1997?

Yefim from Yuzovka with a Cardboard Camera

Yefim Khaldei was born in March 1917 in Yuzovka (now Donetsk) in the family of a grocer. His life began harshly: he became an orphan and got a bullet in his lung. When he was only one year old, his family fell victim to a pogrom against Jews. His father Ananiy and older siblings managed to hide. Yefim’s grandfather and mother were killed. Anna was holding her son in her arms when she was shot. The bullet went through her body and hit the baby's lung. Yefim survived.

The boy was brought up by his grandmother in strict religious tradition. He went to the synagogue and graduated from four classes of cheder, an elementary school. His childhood passed under the “Lament of Israel”: for five kopecks, his grandmother made the boy play her favourite melody on the violin. Yefim liked to look at pictures in magazines and he often annoyed the employees at the Kleymanov Brothers’ photo studio with his curiosity. In the end, they took Yefim as an apprentice. And already at the age of 14, he “signed up” for a camera. Today we would say: "he got it on credit". Prior to this, Yefim had a homemade device made of cardboard, lenses from his grandmother's glasses, and manganese.

From the age of 13, he worked at a locomotive depot and travelled around Donbass as a part of an agitprop brigade. He photographed shock workers of Communist labour and Stakhanovites for the wall newspaper. Local editors liked his photos, and in the 1930s several photos even won prizes at the All-Donetsk photo exhibitions.

In 1936, Khaldei was invited to Moscow. He was only 19 years old and had already started working at the newsreel with the Soviet press agency TASS as a photo correspondent. At the same time, he changed his name to one more common in Moscow – Yevgeny.

Victory Banner Brought Under His Jacket

At the agency, just after returning from a working trip to Tarkhany, he learned that the war had begun. At the time, the TASS photo newsreel was located on 25th October Street (now Nikolskaya Street). The young photographer looked out the window. People were gathering under a speaker, and they were discussing something. Khaldei ran out into the street and took his first wartime photo: Muscovites listening to People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the Soviet Union Molotov's report about Germany's treacherous attack on the Soviet Union.

Before being sent to the front, Khaldei received only 100 metres of film tape from his editor. They said there was no need for more, in a couple of weeks the war would be over. But between that remark and Khaldei’s last photo of the war – Raising the Victory Banner over the Reichstag – 1,418 days passed. During that time, Evgeny Ananyevich photographed a whole military chronicle. In the rank of Navy Technician-Intendant 1st class, he captured the battles for the Arctic Circle, the battles for Sevastopol and Kerch, the liberation of Romania, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Hungary, and, finally, the capture of Berlin.

Just a couple of weeks before the victory, he nearly lost his life. There were almost no beds in the room where Khaldei and his comrades-in-arms were accommodated for the night. The photographer had a mattress on the floor. At one point, when somebody else's place on the bed was free, he decided to sleep there. His comrade came back and, of course, asked for his bed back. Khaldei had barely managed to get up from the bed when a high-explosive bomb crashed into it.

Much later, Yevgeny Khaldei spoke about how he took his perhaps most famous photo – Raising a Flag over the Reichstag. He did not hide the fact that it was staged. The cloths (not one, but three) were made of red tablecloths back in Moscow.

Khaldei, together with his old friend and fellow countryman Israel Kishitzer, a tailor, cut fabric and sewed sickles and hammers carved from white sheets. Khaldei exchanged the red bunting cloths for two bottles of vodka from Grigory Lublinsky, a supply manager at the TASS newsreel, and promised to return them soon. To keep the plan a secret, the photographer carried the banners covertly: he wrapped them around himself, put a jacket on top, and got to Berlin.

Yevgeny Khaldei had a personal account with the Nazis. They finished the deed started in 1918 by the Black Hundreds. In 1941, the Gestapo killed his father and three sisters. They failed to leave Donetsk before the Germans came – they were digging trenches. When the fascists occupied the city, the Jewish family was turned in by their neighbours.

Göring’s Most Hated Photographer

At the Nuremberg trials, three military photos taken by Yevgeny Khaldei were admitted as evidence of Nazi crimes and presented in the court. These were photos of the destroyed city of Sevastopol, victims in the yard of a Rostov prison, and the chimneys of burnt-out Murmansk houses. Murmansk was entirely made of wood, so when the city burned down after a German air raid, there were only stoves left of it.

In Nuremberg, Khaldei was accredited as a photojournalist by TASS. "I went to shoot revenge", he said. From this trip, he would have taken the same images as everyone else: pictures of the city ruins, general plans for the courtroom, and highlights available to all photographers. But he wanted to capture something special.

The main subject of interest of the public and the press were the defendants, especially Hermann Göring, the number-two Nazi. Yevgeny Ananyevich puzzled over how to shoot Göring in such a way that one could get a unique photo. Khaldei found a way to get it. The photographer agreed with the secretary of Iona Nikitchenko, a chief Soviet judge at the Nuremberg trials, to take a place in the secretariat for a short while, from where a great angle was wide open. In exchange for two bottles of whiskey, the secretary agreed to wait after a break between the morning and evening sessions.

Khaldei tried to act at ease: during the break, he put the camera on the floor so that no one would notice it (the camera was not small, Speed Graphic was designed specifically for photojournalism) and took the secretary's seat. At the right moment, when Göring was called in for cross-examination and two American soldiers standing on either side of him stretched out and picked up their batons, Khaldei gently clicked the shutter. That photo was published in newspapers around the world.

Khaldei took a risk. It was a serious breach of discipline. The American guard who was in charge of courtroom procedures could easily have taken the Soviet photographer out and revoke his accreditation.

The Speed Graphic camera was presented to Yevgeny Ananyevich by Robert Capa, the founder of military photojournalism. Capa took a photo of Khaldei standing with his Speed Graphic near Göring, who was covering his face with his hand. The reason for this unfriendly gesture was precisely Yevgeny Khaldei. One day, even before the incident at Göring's cross-examination, photo reporters, including Khaldei, went down to the prison dining room during

lunchtime to shoot the prisoners' life. As soon as Khaldei appeared, and he was wearing a Soviet military uniform, Göring kicked the table with his fist and started talking loudly. Then one of the American soldiers hit the raging Nazi with a baton on the neck; Göring calmed down and no longer prevented the shooting. And in the courtroom, he decided to take revenge – covering his face with his hand.

Fifth Point

After victory, Khaldei’s life seemed to be particularly successful. He photographed Zhukov and Stalin; he was the only Soviet correspondent sent to shoot the Potsdam Conference in the summer of 1945. But in 1948, an “anti-cosmopolitan campaign” started in the USSR. Among other things, Jews were massively fired from visible positions. Yevgeny Khaldei also suffered this fate. He and four other colleagues were fired from TASS, allegedly for political illiteracy and lack of professionalism.

But when those four were reinstated at work and he was not, Yevgeny Ananyevich realised that it was about the unfortunate “fifth point” in the Soviet passport, which stated that he was a Jew. He was reminded that he had been a candidate for the party for eight years, but had never joined it. According to the photographer's daughter, Anna, even the fact that he bought import Kodak roll films on his business trip on the occasion of the Paris Peace Conference was added to the case.

After 1948, the life of Yevgeny Ananyevich saw a difficult period, with no steady job and anticipating coming reprisals. Fearing for himself and his family, Khaldei destroyed the negatives of some of the photos that could have shown unfavourable faces to the authorities. For example, the glass negatives of photographs of actor Solomon Mikhoels, who was killed in 1948.

Khaldei was denied having his photographs printed. With great difficulty, he managed to get a job as a freelancer in the trade union magazine “The Club and Amateur Art-Making”. For the “Club”, the war correspondent took pictures of, as he himself put it, “jump-up dances” - stories of a completely different kind.

It was only in 1959 that Yevgeny Ananyevich was welcomed to the Pravda newspaper. But not without the help of the poet Konstantin Simonov. He worked there for 13 years, until a new man took over the post of chief human resources officer at the country's main newspaper. This is how Yevgeny Khaldei told this story in a documentary film dedicated to him: “A new head of the Human Resources Department came in. So, kind of an open anti-Semite. There are closed anti-Semites, and this one is completely open. He says that he will not rest until not one Jew works in the newspaper. None was left. And then they got to me, so to speak, they were picking on me”. So, he had to look for another job. From 1973 to 1976, Khaldei was shooting for the magazine Sovetskaya Kultura, and then he retired.

"Where Are You From, Soldiers?"

The fate of Yevgeny Khaldei is worthy in itself to go on camera. However, a film about him was made only in 1997 by Belgian Marc-Henri Wajnberg. Two years earlier, in Perpignan, the French awarded Khaldei the title Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters, the highest award of the French Ministry of Culture.

For publishing one small photo in Time, he once received a reward of $200. His pension at home was six times less. “On salami. Everything goes on salami. Sometimes on sausages”, Khaldei said, showing in the film an envelope containing the American royalties. The master had not lost his zest for life.

As a true documentalist, Khaldei remembered everyone who got caught in his lens, knew their names, followed their fates - he could tell the story behind any photo. He persistently looked for his heroes, addressing readers on the pages of newspapers where the photos were published.

In his photo album “From Murmansk to Berlin”, Khaldei recalled: “My story about how the photo was taken ended with the question: Where are you from, soldiers?” And they answered me: "We came from Stalingrad. We are from Sevastopol. We are from Kursk, Bryansk". Khaldei received letters with his photographs, where some faces were circled – people recognised their loved ones. Or they asked the photographer if it was their relatives and asked him to send some information.

30 years after the victory, Yevgeny Ananyevich met many of the heroes of his photographs to take pictures of them again, but already surrounded by their grandchildren. It was as if he felt responsible for their fate. Already retired, Khaldei released an album with these works.

Also, he easily trusted people. Unfortunately, there were those who exploited this. In 1996, an American gallery owner offered Khaldei to exchange his "Leica", with which he walked from Murmansk to Berlin, for a similar camera on the condition that Khaldei’s legendary camera would be placed in the Los Angeles Photography Museum. As his daughter Anna explained, this man sold "Lecia" at an auction for 200,000 dollars, and it did not appear in the museum. Khaldei never found out about this. He died in October 1997.

“All leaders went through my lens: Stalin, Khrushchev, Brezhnev, Andropov, Chernenko, Gorbachev, Yeltsin... And who will be the next one? I don't know if I can take his picture...” Khaldei reflected in the Belgian documentary. A year after his death, his first solo exhibition opened in Moscow.