For over 30 years, Martin Bormann, head of the Nazi Party Chancellery, was considered one of the most wanted international criminals. With no verifiable evidence of his fate at hand at the time, the International Military Tribunal tried him in absentia.

Early in the 2000s, the CIA released classified documents that allow one to piece together the history of the search for Bormann, though the real cause of his death will probably never be established.

Murderer and Secretary

Born in 1900 into the family of a post office employee, Martin Bormann studied at an agricultural high school and was a simple farmer prior to the beginning of his political career. In his youth, he joined the ranks of the Freikorps, a paramilitary volunteer organisation which continued the militaristic tradition in Germany despite the ban imposed under the Treaty of Versailles.

In 1924, Bormann was tried and sentenced to a year in prison as an accomplice to his friend Rudolf Hoss – the man who would become the commandant of the infamous Auschwitz concentration camp – in the murder of a school teacher named Walter Kadow.

In 1925, Bormann joined the Nazi Party. Four years later, Bormann married the daughter of one of the Nazi Party elite: the father of his wife Gerda Buch was chairman of the party's supreme court; Adolf Hitler, Heinrich Himmler and Rudolf Hess became godfathers to some of Martin's and Gerda's children.

The relationship between Martin and Gerda raised quite a few eyebrows as, for example, when Bormann's affair with actress Manja Behrens came to light, his wife actually supported him.

“I like M. myself, so I can't be mad at you; the children also like her very much,” Gerda wrote in a letter dated 21 January 1944. “In any case, she is much more practical than me.”

Bormann's career in the Nazi Party advanced by leaps and bounds, as his adherence to the national socialist ideology, sense of duty and his cunning helped him make his way into the top echelons of power. Bormann's curriculum includes administrative positions in Thuringia, in the supreme command of the SA, in the Nazi Party Auxiliary Fund, and in the office of Rudolf Hess, whom Bormann replaced as head of the Nazi Party Chancellery after Hess' failed mission to Britain.

From May 1941, Bormann's influence within the Nazi Party started to grow, with all laws and decrees in the Reich being affirmed with his signature. An opponent of religion, he conducted a harsh policy towards theological faculties, churches and synagogues in Germany, demanding their abolition.

Having assumed a position which gave him control over Hitler's entire correspondence with the Reich's top officials, Bormann schemed against those he didn't like; by the end of the war, Himmler and Goering had lost the Fuhrer's trust, while Bormann became his right hand.

As former Nazi Minister of Armaments Albert Speer wrote in his memoir in 1970, Bormann stood out due to his “cruelty and rudeness”, was “uncouth” and treated his subordinates “as cattle”, which Speer, likely mockingly, attributed to Bormann's agricultural past.

So how could such a man become “Nazi Number One”? Bormann's obedience and sense of duty were unmatched. He never argued, and always followed his boss in all personal and business trips, becoming referred to as “Hitler's shadow”.

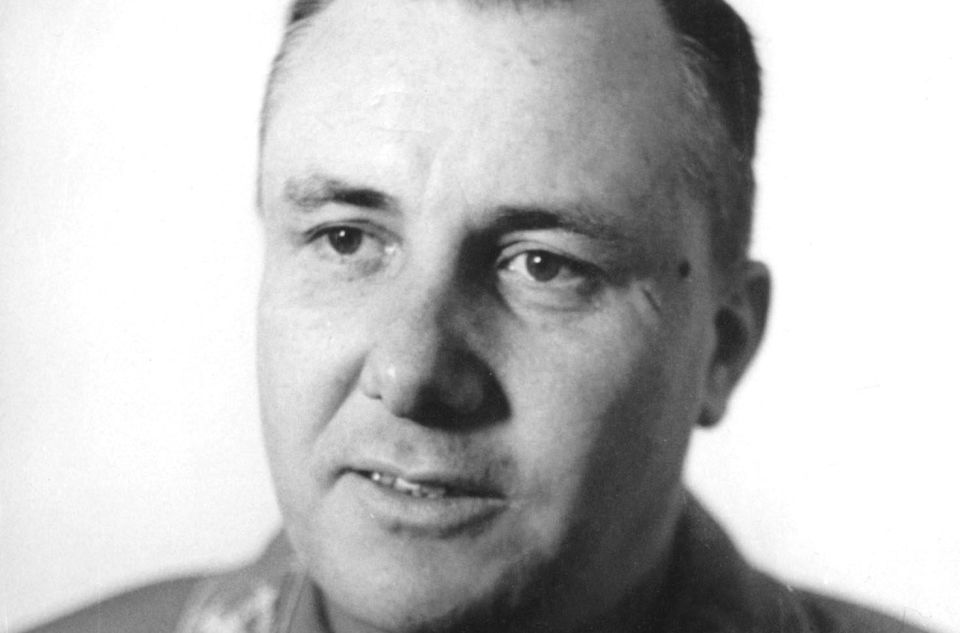

At the same time, he was rarely filmed or photographed. He always carried a notebook, which he used to record his Fuhrer's every wish – not a single word was to be missed. Hitler's closest ally, he first witnessed the Fuhrer's marriage to Eva Braun in the Fuhrerbunker, and then watched their bodies burn.

There, in the Fuhrerbunker, Hitler gave Bormann two wills – one personal, the other political – in which he appointed the latter as the executor of his estate and the de facto head of the party.

After 2 May 1945, however, Bormann's trail runs cold.

Somewhere Between the Alps and the Cordilleras

During the Nuremberg Trials, Bormann was tried in absentia, with the proof of his crimes being presented by a member of the US prosecution team named Walter Brudno.

Half a century later, the CIA, having an extensive network of agents spanning Europe and Latin America, attempted to hunt Bormann down.

Early in the 2000s, the agency unveiled a trove of documents called the Nazi War Crimes Disclosure Act, which included materials related to Bormann's identity and the history of the search for him.

The information about the war criminal's possible whereabouts was supplied to the CIA (known as the OSS until 1949) almost every year, with Bormann sometimes allegedly being spotted in several separate places at once.

This hardly comes as a surprise, since Bormann's appearance was fairly nondescript: he had a short stature, robust physique, short hair, grey eyes, and a yellowish complexion. Few people could recognise his face, so the agency sent photos of him to US embassies and NGOs across Europe and South America.

Some rumours, eventually proven untrue, claimed that Bormann was hiding in the Argentinian embassy in Rome. In 1947, informants in Madrid claimed that Bormann was in Argentina where he arrived in a submarine, carrying Hitler's will with him.

A year later came claims from Ecuador about some sort German colony there, with one of its residents being a man who had taken great care to conceal his face and whose description resembled Bormann's.

At that time, an inspector from Scotland Yard shared his suspicions with US intelligence about Bormann possibly hiding in southern Tirol, a hard-to-reach place where the fugitive could allegedly bribe local cops.

In 1949, rumours placed Bormann in Catalonia, where he was allegedly writing his memoir. Other claims portrayed Bormann as living the life of a Catholic monk, or working for Soviet intelligence. The authorities in West Germany even placed a $25,000 bounty on his head, but no one seemed keen to claim it.

Bormann's family was also being watched, as his wife Gerda fled with their nine children to South Tyrol, Italy, and then South America, which was the place where the majority of alleged sightings were reported. Gerda, however, claimed that she knew nothing of her husband's whereabouts.

The questioning of Bormann's brother, Albert, also yielded little as he said he hadn't seen Martin since 21 April 1945 and believed him to be dead. Albert did not deny, however, that between 21 April and 2 May 1945, his brother could've been ferried to any of the aforementioned countries.

Truth in the Teeth

In 1972, human remains were found during road construction in the vicinity of the Central Station in Berlin, and while the police had previously received reports about Ludwig Stumpfegger, the personal surgeon of Bormann and Hitler, being killed there, that line of inquiry hadn't been thoroughly pursued before.

It was a Norwegian dentist named Reidar Sognnaes who helped shed light on this mystery. Previously, Sognnaes gained fame by conducting an independent examination of the descriptions of Hitler's dental prosthesis kept in US archives, confirming that Soviet troops did indeed find the Fuhrer's remains in Berlin.

The results of his examination of Bormann's alleged remains, along with records of the Nazi official's dentist, were presented by Sognnaes at the World Dental Congress in 1974. There, Sognnaes established that a dental bridge found among the remains found in Berlin matched the description of a dental bridge installed by Bormann's dentist, with the dental prosthesis fitting Bormann's lower jawbone perfectly; traces of cyanide were also found on the jawbone.

That hypothesis was eventually confirmed in 1998, when a DNA analysis of the remains (with Bormann's son providing his genetic material for comparison) yielded positive results.

Martin Borman died on 2 May 1945. His remains were cremated, and his ashes were scattered over the Baltic Sea.

Flight in the Night

So what happened on 2 May 1945 in Berlin? Eyewitnesses' accounts of Bormann's attempted escape differ from one another.

Hitler's surviving cohorts were fleeing the Fuhrerbunker in organised groups. The third group included Bormann, Stumpfegger, Hitler Youth chief Artur Axmann, and also Erich Kempka, Hitler's primary chauffeur.

On 3 July 1946, Bormann's defence counsel Friedrich Bergold questioned Kempka, who said that he last saw Bormann during the night between 1 and 2 of May 1945, near the Weidendammer Bridge in Berlin, in the vicinity of the Friedrichstrasse train station.

Their group was planning to get across the Spree river on foot, being escorted by several armoured vehicles. Bormann was resting his hand on the side of the lead vehicle as he walked, yet as they passed the anti-tank barriers, that vehicle was blown up by a Soviet shell.

According to Kempka, he lost consciousness then and doesn't know what happened next; allegedly, he hasn't seen Bormann since.

So what in Kempka's testimony puzzled the court? First, he was allegedly a mere 3-4 meters away from Bormann, yet he emerged without a scratch after the ensuing explosion. Second, his testimony contradicted Axmann's.

The Hitler Youth chief managed to escape and lived for several months under a false name, until US counterintelligence finally found him in December 1945.

During questioning, Axmann said that, together with Bormann and Stumpfegger, he managed to get across Spree and were heading towards the train station along the tracks. At some point, he parted ways with Bormann and Stumpfegger and walked in the opposite direction, but turned back after spotting a Red Army patrol.

On a bridge at Invalidenstrasse, near the train station, he saw two bodies, and in the moonlight, he managed to recognise their faces – they were Bormann and Stumpfegger. Being in a hurry, however, he didn't stop to try and determine how they died.

Contradictions in these testimonies, the absence of the body and the lack of other witnesses of Bormann's demise led to the continuation of the search for him.

The results of the discovery of 1972, the examination of 1974 and the DNA testing of 1998 allow one to assume that Bormann committed suicide by taking a cyanide pill.

However, it remains unclear why Bormann and Stumpfegger might've opted to take their own lives (assuming that that's what actually happened, of course) – perhaps they ran into a Red Army patrol and were injured or realised that there was nowhere to run.