On 20 November 1945 the surviving leaders of the Nazi regime in Germany went on trial in the Bavarian city of Nuremberg. They were put on trial on the basis of a set of legal principles which would become the bedrock of international law on war crimes and genocide for 75 years.

When the Nuremberg trial began in November 1945 there were many in Britain, France, the United States and the Soviet Union who thought it was a waste of time and money.

Many people favoured summary justice for Hermann Goering and the 23 other Nazi leaders - just line them up and shoot them with a minimum of fuss.

Klaus Rackwitz, director of the International Nuremberg Principles Academy, explained why the Allied leaders realised executions without trial would be counter-productive.

"They were very smart to realise that the only consequence of that would be a kind of legend-building around those who had just been shot and hadn't even had a chance to explain their position," Mr Rackwitz, a former judge in Germany, told Sputnik.

Germans Warned by Moscow Declaration

Preparations for the Nuremberg trial began shortly after the Moscow Declaration in October 1943, when the British, American and Soviet leaders warned the Germans there would be a reckoning at the end of the war.

In a joint statement by Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin, they said: “We have received from many quarters evidence of atrocities, massacres and cold-blooded mass executions which are being perpetrated by Hitlerite forces in many of the countries they have overrun and from which they are now being steadily expelled."

The statement went on to say: "At the time of granting of any armistice to any government which may be set up in Germany, those German officers and men and members of the Nazi party who have been responsible for or have taken a consenting part in the above atrocities, massacres and executions will be sent back to the countries in which their abominable deeds were done in order that they may be judged and punished according to the laws of these liberated countries and of free governments which will be erected therein."

Goering and some of his co-defendants would often claim they were only on trial because Germany had lost the war.

Nazis' War Crimes Incomparable With Allies'

But Mr Rackwitz said: "The scale of atrocities committed by the Germans was so outrageous that you could not find anything comparable on the Allied side."

The International Nuremberg Principles Academy is funded by the German federal government, the Bavarian state and the city of Nuremberg, which has been dubbed the "city of human rights."

There were seven Nuremberg Principles - which were later carved out by the International Law Commission of the United Nations - which were the legal basis of the trial.

The first, and most important, was that "any person who commits an act which constitutes a crime under international law" is responsible and liable to punishment.

'I Was Only Obeying Orders' - Not an Excuse

One of the most apposite principles when it came to the Nazis was that a person was not excused responsibility because they were “acting under orders from a superior.”

So many of the defendants at the trial used this excuse - what is known in German as "Befehl ist Befehl" (an order is an order) - that it became known as the Nuremberg Defence.

Mr Rackwitz said: "This is the main benefit of the Nuremberg Principles, that it pre-empted potential defence lines that one can foresee - 'I have been ordered to do so', 'I was responded to crimes on the other side', 'I have been the leader of a state'."

He said the Nuremberg Principles have never been formally adopted by the United Nations or the international community but they remain at the heart of the trials for genocide and war crimes.

Another Nuremberg Principle was that anyone accused of a crime under international law “had the right to a fair trial”.

Mr Rackwitz said the parameters for Nuremberg were influenced in part by the Leipzig war crimes trial after the First World War, or rather for what was omitted from that trial.

The Holocaust was not the first time a race was targeted by a government - between 1914 and 1923 more than a million Armenians had been killed by the Turks.

Mr Rackwitz said: "People realised that the focus of the Leipzig trial was way too narrow. What the Leipzig trial covered was only breaches of The Hague Convention, it was only about war crimes in the narrow sense, nothing about aggression or mass atrocities or complicity, it was only targeting actual military leaders right down to platoon commanders that had committed crimes, like having prisoners of war starved or attacking hospitals."

By the time the Nuremberg trial began in November 1945 Hitler, Goebbels and Himmler were dead but Goering was joined in the dock by Adolf Hitler's deputy Rudolf Hess, the Nazis' foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and the Nazi governors of occupied territories in Eastern Europe.

Another top Nazi Martin Bormann was not on the accused bench but was tried "in absentia." His remains were found in Berlin in 1972, although he was believed to have died at the end of the war.

The Eight Nuremberg Judges

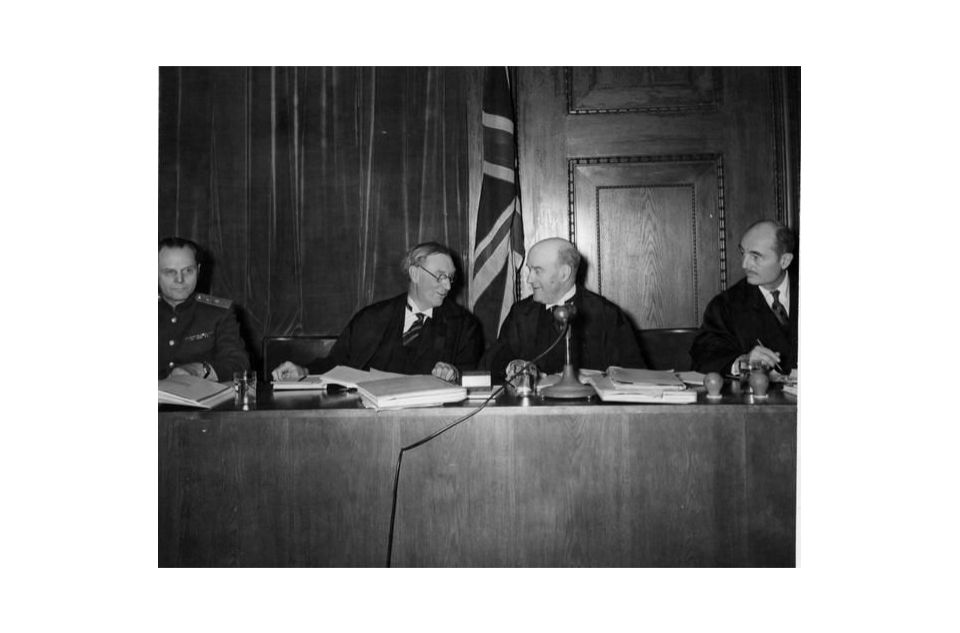

Nuremberg was a military tribunal whose eight judges represented the allied powers - two each from the United States, Britain, the Soviet Union and France.

Britain was represented by Norman Birkett, a high profile London criminal lawyer and former Liberal MP, and Geoffrey Lawrence, a veteran of the First World War, who was the presiding judge.

On 1 October 1946, 12 of the defendants were sentenced to death, seven to long prison sentences and three were acquitted.

Mr Rackwitz said it was a shame the Nuremberg Principles were not adopted by the international community in the early 1950s when the Cold War put on ice co-operation between the US, UK and France on one side and the Soviet Union on the other.

“I do believe that the deterrent effect of these principles would have been greater and would have been more meaningful if they had been codified into a convention,” he said.

Could Nuremberg Principles Have Prevented Biafra or Yugoslavia?

"Whether it would have prevented wars from taking place is speculation…I do believe if after the Korean War, and the Vietnam War, and the Biafra war when mass starvation was used as a weapon of war for the first time, I do believe it would had a deterrent effect," Mr Rackwitz said.

"I'm pretty sure (Slobodan) Milosevic wouldn't have started the Yugoslav war if he would have been knowing already at the very beginning that you will end up with a lifetime in prison," he claimed.

Mr Rackwitz said one of the Principles - that if someone is a head of state or senior government official “it does not relieve him from responsibility under international law” - was still being challenged today.

In 2002 the International Court of Justice ruled that a Belgian arrest warrant for Abdoulaye Yerodia Ndombasi, a minister in the Democratic Republic of Congo accused of inciting genocide against ethnic Tutsis in the east of the country, was not valid because he was immune from prosecution.

Impunity Still Being Sought For Heads Of State

Mr Rackwitz said neither South Africa or Jordan had detained the former Sudanese leader Omar al-Bashir - who was accused of war crimes in Darfur - despite an international arrest warrant and he said Kenya has tried to get temporary impunity from prosecution for heads of state.

He said some of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council had blocked international war crimes prosecutions in recent years.

"The trouble is that the Nuremberg Principles have been decreasing in their value. They are now just one element of international law and not the over-arching element," said Mr Rackwitz.

He said many world leaders still believed there was such a thing as a "just war" and added: "As long as we have that as a dogma - 'because my party is doing the right thing and they are legitimately defending themselves against rebels then it’s a just war and I don't want to put him on trial' - I'm sorry but even if it’s the most just war in the world if there are war crimes committed someone needs to stop that."