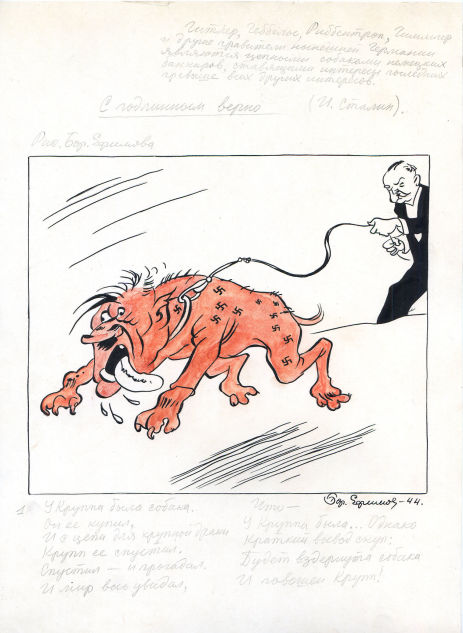

Before Disney shaped our perception of dwarves in its animated films, they were known through German fairy tales as hardworking but morally unscrupulous craftsmen. These are apt words for describing the Krupp dynasty: its history is a synthesis of purposefulness, calculation and cynicism. The last of the Krupps industrialists did not care about the moans and groans that echoed in his factories; they were little less than a line item in the bill of sale for each gun, tank or submarine presented to the Reich. And every death (be it of a German or an enemy combatant, it didn’t matter) brought the dynasty money, rewards, and glory. Peter Romanov offers his view on the history of the dynasty.

Crown Given by the Russian Empire

The Krupps became known as “Cannon Kings” in 1863 thanks to an order received from Russia for a grandiose sum of one million thalers. The deal made a strong impression on the world, and earned the family their alias.

At first, the military did not trust steel. The first-generation steel cannons exploded after several shots. The Krupps sent their guns as a gift to several countries, but insisted on testing them using field-tests. This is how the Krupp’s steel cannon got to the Russian gunsmiths. Day after day, they fired this gift. After 4,000 shots, they scrupulously examined the barrel, and did not find as much as a scratch. The miracle gun was sent to the Peter and Paul Fortress, to the Museum of Artillery, and the Krupps received an order. His cannons did a lot of work in Russia. The 42-line battery field gun model 1877 was actively used in the Russo-Japanese War, World War I, and the Civil War. These cannons were produced both at the Krupp factories and at the Obukhov State Plant in St. Petersburg.

The Krupps started frugally, having tried many ways to get rich. They failed many times, but finally, they found a way to make first-class steel, and then turn it into gold. They dedicated themselves to the arms trade. They were hard-working, like dwarves, forging more and more deadly weapons. The Krupps even supplied those who fought against Germany with guns at the time, through intermediaries. During the First World War, Friedrich Krupp was considered the main supplier of armoured shields and plates to the British artillery and navy. The papers of the British company "Wickers" featured special expense items with a brief note "K". According to these documents, the British had to pay Gustav Krupp about 60 Deutschmarks for each fallen German soldier.

The Krupp dynasty, like any other, was not eternal. In 1966, Arndt Krupp, the last man to receive this name at birth, renounced both the right to his inheritance and the family name in exchange for an annual rent of two million Deutschmark. Arndt was a cad, a heavy drinker and a homosexual (which, however, didn’t stop him from marrying a princess.) A year before he passed away, Arndt’s father and the owner of the family business, Alfried Krupp, had agreed to “abdicate the throne”. He transferred all the capital of the concern to a foundation established in his name.

The “death certificate” of the dynasty can be dated to a later period. In March 1999, a document was signed on the merger of the two industrial giants of Germany – Thyssen AG and the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation. This is how the largest European industrial concerns, ThyssenKrupp AG, one of the world's leaders in steel production, was founded. The Foundation's share in the assets of the company totals €15 billion.

The Krupps Get on Track

The merchant Arnold Arndt is often called the founder of the dynasty. There are documents from the late 16th century mentioning a resident of Essen by this name. Neither he nor the other early Krupps had anything to do with the family's rise to economic power. They were not interested in metallurgy and owned shops. One of them served as burgomaster of the city of Essen.

All of that changed in the second half of the 18th century, when the family was headed by Helene Amalie Krupp. It was she who turned the humble colonial goods shop she inherited from her husband into a hive of industrial and commercial enterprises, including metallurgical ones. Three years before her death, Helene Amalie gave her grandson Friedrich a gift, a metallurgy plant. Friedrich failed to manage the gift, and his grandmother took it back. But after her death in 1810, he inherited all the property of the Krupps and established a company with the remarkable name “Friedrich Krupp in defence of English cast steel and related products”. He had planned to fill an obvious niche at the time. Due to the Continental System, the blockade designed by Napoleon to paralyse Great Britain, which was the main supplier of steel to the continent, there was a need for the alloy. However, the blockade was soon lifted, and it was not until 1816 that Krupp succeeded in making steel that was comparable in quality to the imported English variety. His company produced tools for the leather industry, drills, turning chisels, coin stamps and bells. By the time of Friedrich's death, it was a modest company with seven employees.

The great-grandson of Helena Amalia, Alfred, brought the Krupps fame throughout Europe. After he inherited his father's factory at the age of 14, he raised it from its knees and set up new production: railcar wheels which didn’t have welding seams. Steel wheels made the Krupps successful; they were installed on most of the train carriages in Europe and America. The wheels are depicted on the official emblem of the company. Over time, Alfred became interested in manufacturing artillery, started producing guns and won the title of “Cannon King”. It was Alfred Krupp who successfully courted the Tsar.

The dynasty was unlucky with its next heir. Friedrich Alfred Krupp (Fritz) was not very interested in business; he spent more time on the island of Capri. He was interested in zoology, not in steel. He discovered and classified thirty-three new species of "free-floating life forms", as well as five species of sea worms, four species of fish, twenty-three types of plankton and twenty-four species of crustaceans. Fritz mostly kept the company of boys and young men. At first the Italian, then the German press raised a loud scandal about it, but German Emperor Wilhelm II suppressed the inappropriate story. The same approach was taken to talk about Fritz's mysterious death – many researchers claim that he committed suicide.

In spite of his peculiar tendencies, the head of the dynasty fulfilled his duty: he got married and became the father of two daughters. The younger one did not play any role in history, but the elder one, Berta, became world famous.

“Big Bertha” of Mass Destruction

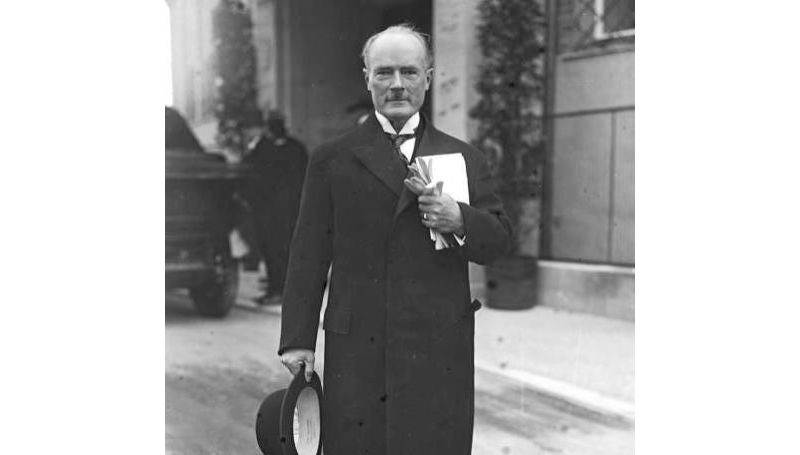

A woman, even one with the name, blood and character of the Krupps, could not stand at the head of the arms conglomerate. And it was hardly a pleasure for her. The books about Krupps tell how the sisters tried to familiarise themselves with steelmaking. The girls were taught the nuances of smelting, they listened carefully, but then admitted that they did not understand a thing. As a result, Kaiser Wilhelm had to personally attend to the matter of of Bertha's marriage. Rather than choosing an industrial giant as a husband for the heiress, he picked a leading German gunsmith. The choice fell on a nobleman: Gustav von Bolen. He was a smart entrepreneur (his family owned blacksmiths) and a diplomat who managed to work in German diplomatic missions in Washington, Beijing and the Vatican.

What the Emperor said to the bride and groom during the match-making in 1906 is unknown, but they obeyed. Gustav even agreed to take his wife's name. A successful marriage and loyalty to German military ambitions eventually led him to the Nuremberg trials and prison.

Every military man learned the name of Gustav Krupp's wife in World War I. The howitzer “Big Bertha” (the soldiers called it “Fat Berta” or simply “Fat Girl”) was used to destroy particularly strong fortifications. All modifications of the artillery mortar were really big, weighing from 42 to 140 tonnes. The most long-range mortar fired shells weighing 1,160 kg 12.5 kilometres.

The Krupp’s “Big Bertha” is what some researchers call the precursor of weapons of mass destruction. And by no accident. A high-explosive shell formed a funnel 4.25 meters deep and 10.5 meters in diameter. A fragmentation shell splintered into 15,000 pieces of metal, which retained their killing power at a distance of up to two kilometres. Slabs of steel and concrete walls two metres thick did not save enemy combatants from the armour-piercing shells. It took only two of Krupp’s howitzers and 360 shells to force a fortress’s garrison of 1,000 men to surrender within a day.

The “Big Bertha” participated in the capture of Liege in August 1914 and the Battle of Verdun in the winter of 1916, as well as the capture of Russian fortresses Novogeorgievsk and Kaunas. Some even write as if “Big Bertha” shelled Paris in March-August 1918. However, this is not true. To siege the French capital, the Krupps made a special super-long-range cannon, the “Kolossal” or “Paris Gun”, which had a range of up to 120 kilometres.

Gustav Clenches His Jaw

As soon as the ceasefire was declared in World War I, military orders stopped and there was nothing to pay the workers. The company almost went back to the way it had been in Friedrich's time; the Krupps began making rolls for cutlery and parts for baby carriages. Gustav said that the company was ready to consider any ideas and pay for successful ones. One Krupp’s advertising poster had only one word on it: “Jaws”; it promoted steel dentures.

Gustav Krupp wrote at the time: "If there is ever a resurrection of Germany, the company needs to prepare. The equipment has been destroyed; machines have been destroyed. But there is one thing left – people in design bureaus and workshops who through successful cooperation have brought arms production to its final perfection. Their skills need to be preserved, as do their vast resources of knowledge and experience (...) for a distant future, despite all the challenges.”

Once Krupp had to spend four months in prison. There was a bloody clash between workers at one of the factories and 13 people were killed. Krupp's managers and Gustav himself were put in jail.

And yet he managed to get the Krupp’s business back on track, and in the literal sense: his companies started producing steel elements for railways. As for the weapons, it turned out that its production never stopped.

Krupp skilfully bypassed the Treaty of Versailles, a ban on arms trade and production. This document did not refer to German production located in other countries. That is what Gustav was using. His engineers and technicians worked, for example, at the Swedish steel makers Bofors. The assembly lines of this factory were used to produce Krupp products: artillery systems, anti-aircraft guns and even experimental armour-piercing shells. The weapons were sold to the Netherlands, Denmark and other countries.

In 1922, following a secret agreement with the German Naval Ministry, Gustav Krupp founded a concern in the Hague known as the Suderius AG (SAG), which meant the “Shipbuilding Engineering Office”. The company's task was to continue developing submarines. Gustav sent a design team to shipyards in the Netherlands, where SAG designed and built submarines for other countries. Krupp exchanged information with Japanese submarine builders and sent his chief designer to this country. The head of the company also sent copies of the drawings and design staff to Finland, Spain and Turkey. In turn, these countries allowed German submariners to conduct test trips on new submarines – they were banned from sailing under the German flag.

The Treaty of Versailles prohibited Germany from producing weapons - but not designing them. Gustav kept arms development teams in Essen and provided them with military and technical publications from around the world. His engineers studied other people's inventions and patented many of their own.

“How far we have fallen”

During World War II, the factory in Silesia was named after Bertha, where the famous Schmeisser automatic rifles were assembled. Berthawerk (from “Bertha” and “Werk” meaning factory in German) was home to prisoners from Auschwitz. Another Krupp factory was located in the death camp itself. According to one of the employees, a witness at the Nuremberg trials, the three pipes of the crematorium could be seen from the windows of the plant.

Judging from the way the husband gave his deadly creations his wife's name, their family life was a success. According to the memories of her contemporaries, Bertha was a stern woman with a straight, unbending back and looked like a Teutonic Knight. Unlike her husband, who adored if not Nazism, then personally the Fuhrer, Bertha treated Hitler like a Johnny-come-lately. When Hitler first visited the Krupps’ house, Bertha refused to meet him, saying she had a migraine. And when Gustav hung a Nazi flag on the house, she scornfully pointed it out to her servant, saying: “Look, how far we have fallen!” Bertha, however, almost never intervened in her husband's affairs.

Valentin Berezhkov, a representative of the Soviet Procurement Commission of Military Equipment, described Gustav Krupp as follows: “A skinny old man with a hard look and a parchment face.” The "old man" did not deny his loyalty to any of the German rulers. He cooperated with German Emperor Wilhelm II, then with the leaders of the Weimar Republic, and starting in 1933, he firmly put his money on Adolf Hitler. He faithfully served the Third Reich until 1941, when he suffered a stroke and was struck by paralysis.

For forty years, this man had been scrupulously managing a concern where everything belonged not to him, but Bertha. And Gustav did his job earnestly. It was he who managed to revive the company after Germany's defeat in World War I. And then he supplied Hitler with everything he needed for his military revenge. For which, among other awards, Hitler even awarded him the Golden Party Badge of the NSDAP, a special award for the oldest members of the Nazi party.

Following the war, the paralytic was arrested at his villa in Bluhnbach (Austria) and sent to a small hotel next door, where he was imprisoned. Bertha attended to her husband until his lawyers managed to save him from the gallows. Gustav and Bertha were allowed back to their family villa, where he died in 1950. However, the city of Essen, the cradle of the Krupp empire, crossed both off the list of honoured citizens.

The Last Nazi of the Dynasty

The Nuremberg prosecutors then demanded that his son Alfried, who had been de facto managing the company since 1941, be put on trial instead of Gustav. The lawyers were able to save him as well, but not for long. On 31 July 1948, the American military court in Nuremberg found Alfred guilty of looting European industry and using slave labour. Krupp was sentenced to 12 years in prison, and all of his property was confiscated. However, as early as 4 February 1951, he was released at the behest of the American Military Government in Germany. Moreover, his confiscated property was returned.

Alfried was no mere businessman; he was a dedicated Nazi, the “Führer of the military economy”. In 1931 he’d joined the so-called “Circle of Friends of the SS”. The goal of the organisation of industrialists was to provide financial sponsorship for Nazi endeavours. At the same time, the young Krupp became a member of the National Socialist Flyers Corps and received the title of Standartenführer. He replaced his disabled father as Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Adolf Hitler Fund of German Trade and Industry. Gustav was one of the initiators of the fund, and Alfred made a vital contribution. He also coordinated the activities of military-industrial enterprises in Germany and the occupied countries. Back in the old days, when the Krupps produced saws and bells, there were only seven workers in their factory. But now, not only Germans but also 68,896 foreign workers, 23,076 prisoners of war and 4,978 concentration camp prisoners worked for Alfried. In his hands were the lives of almost 100,000 people who had been reduced to slavery. After leaving prison, he promised to pay compensation to his former “slaves”. But there were only 2,000 people on his list, just two per cent of the total. He kept his promise by spending about $2.4 million.

Three years in prison and a fraction of his capital – this is the toll Krupp paid for his Nazi past, incomparable with the scale of the malevolence that Alfred and Gustav had brought to the world. Krupp's tanks battled the Soviet ones on the Kursk salient, Krupp's “Fat Gustav” and “Long Gustav” guns shelled Sevastopol, Krupp's submarines drowned the Northern Lend-Lease Convoys, and Krupp’s “Schmeissers” killed Soviet soldiers and civilians.