From the opening minutes of the Nuremberg trials on 20 November 1945, all those present in the courtroom realised that they would bear witness to an unprecedented action that had no parallel in history; that this would not be swift justice for the winners, but a complete trial with all its legal meticulousness. The view of the courtroom and the participants of the tribunal astounded eyewitnesses with its rigour and attitude to get down to business. The most perceptive of the defendants even seemed to feel the weight of the rope around their necks.

Сlock of Justice Strikes 10 A.M.

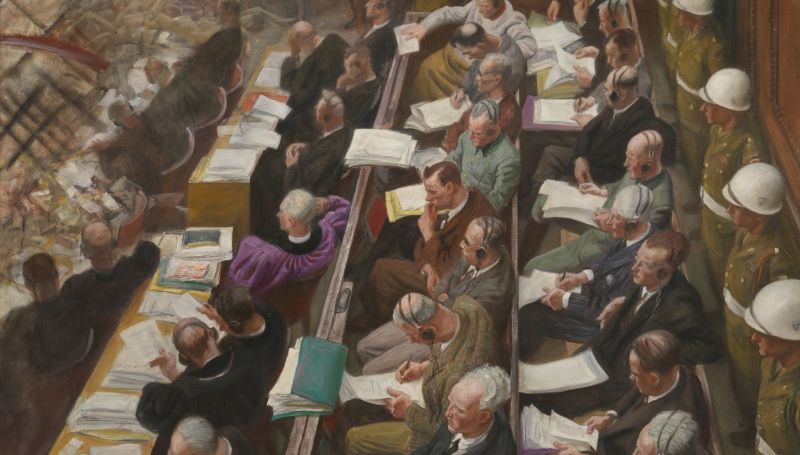

The scuffle of moving chairs, the rustle of paper, somebody's coughing, dialogues in a hushed voice – perhaps these were the first sounds that filled Courtroom No. 600 of the Nuremberg Palace of Justice at 10 a.m. At that moment, there were more than a hundred people present: members of the tribunal, the prosecution and defence, interpreters, journalists, defendants, the American military police, and the audience. But the first words from Nuremberg, spread by radio stations across millions of receivers around the globe, we know for sure. The voice belonged to Sir Geoffrey Lawrence, Lord Justice of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales, President of the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. Here are those exact words:

“Before the defendants in this trial answer the question of whether they are guilty of crimes against peace, war crimes, crimes against humanity and of creating a common plan or conspiracy to commit these crimes, the Tribunal wishes me to make a very brief statement on its behalf... The process that must now begin is one of a kind in the history of world jurisprudence and has the greatest social significance for millions of people around the world. For this reason, anyone who takes part in this process bears a huge responsibility”.

None of those who appeared before the tribunal on 20 November 1945 pleaded guilty. Only one of them would do so later, before being executed.

The Choice of Nuremberg Was Due to Prison

The Soviet delegation insistently proposed Berlin. This was both symbolic and logical – the trial against the upper echelons of the Third Reich should take place in the capital of this very same Reich. But Berlin was a huge city, half-ruined, flooded by allied forces and German saboteurs. The Americans insisted on Munich, also a place of “significance” as it was in Munich that the Nazi idea was born in the 1920s. Besides this, it hadn’t suffered much from the war. But Munich was located in the heart of the American occupation zone and from the Soviet point of view that was a drawback.

In the end, they settled on another Bavarian city - Nuremberg. It was relatively close to the Soviet occupation zone, and if Berlin was the capital of the Third Reich, then Nuremberg was the capital of the NSDAP. Here, the Nazi party held its congresses and torchlight ceremonies at the city stadium. It was here, at another party congress in 1935, that the so-called racial laws were adopted, which became the basis for the extermination of millions of people.

And yet, the main reason why they decided on Nuremberg was different. “The choice of Nuremberg was not only determined by the Palace of Justice located there being almost unharmed during the fighting”, Russian researcher of the Nuremberg trials Alexander Zvyagintsev writes, “The big advantage of it was that there was a prison in one of the wings of the building, and therefore, there was no need to transport the defendants to the courtroom and back. Later, following a presentation by Robert H. Jackson, chief US prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials, everyone began talking about the hand of fate in choosing the place for the trial of the Nazi leaders”.

Berlin became the official location of the tribunal. Its official opening took place a month earlier, on 18 October in a courtroom in the Schöneberg neighbourhood of Berlin. Soviet judge Iona Nikitchenko presided over it. He announced the court’s decision to indict 24 defendants. One month was given to the defendants to get acquainted with this document. At the prison in Nuremberg they reflected on what they read and formulated their answers to the question about whether to plead guilty or not.

For three days - 14, 15, and 17 November - a preliminary session was held in Nuremberg.

During these days, the final list of defendants was formed as a result of the court debate. Gustav Krupp's lawyers managed to "win back" their client, who had lost his legal capacity because of paralysis, and the Reich's largest industrialist was removed from the list of defendants. Lawyers for the head of the Party Chancellery (Parteikanzlei) and private secretary to Adolf Hitler, Martin Bormann, whose fate was still unclear, tried to save their client. The court, however, decided to leave Bormann on the list of defendants. (As it turned out later, the defendant Bormann had died back in May). Another defendant, Head of the German Labour Front Robert Ley, having studied the indictment, put his head in the noose.

Therefore, by 20 November – the first day of the trials – the list of defendants had been reduced from 24 to 22 people, including the deceased Bormann. The public saw 20 of them on the bench – the head of Hitler's intelligence, the Reich Main Security Office, Ernst Kaltenbrunner was “on sick leave”.

The Press – Behind the Glass

"The first thing that catches your eye is the absence of daylight: the windows are tightly curtained. And for some reason, I wanted this hall to be flooded with cheerful sunlight. And through the wide windows, breaking the strict regularity of the court procedure, a variety of sounds of the street would burst here. Let the criminals feel that life has not stopped despite their efforts, that it is beautiful”.

This is how Arkady Poltorak, the Soviet Chief Secretary to the Tribunal, remembers the first day of the trials. Many eyewitnesses to the court describe the dead light of neon lamps - they were installed instead of the luxurious opera-house chandeliers; walls, decorated with oak and dark green marble; bas-reliefs of the figures, symbols of justice. The interior was intentionally designed to immerse those present in a strict, solemn atmosphere.

The visual focus of the audience was on the US military police soldiers lined up behind the defendant's bench. Looking at their accessories, it would be more appropriate to say "toy soldiers" – white helmets, gloves, belts with holster, and even batons. Members of the Soviet delegation stood out – our negotiators achieved the right for Soviet prosecutors and judges to wear uniforms.

Another striking accent was the flags of the four powers behind the backs of the tribunal members. The judge's table was installed on the podium alongside four huge windows, tightly hidden by green draperies. Eight judges, two from each of the victorious countries, towered over all those present. Opposite them were two rows of lawyers' benches (all of them wearing robes), and behind them, "in the amphitheatre", were the defendant's bench, or rather two rows of chairs. At the foot of the judge's table, there were secretaries and assistants of the tribunal members, and further below there were stenographers. To the left of the judges were the prosecutors' desks swamped with heaps of papers. Further to the left, behind the soundproof transparent screen, worked Russian, English, French, and German translators.

Above them on the balcony were the audience and the press. In order not to distract people's attention in the courtroom with flashes and sounds of shooting, a special space with glazed windows was set aside for correspondents. Many of the classic pictures of Courtroom 600 in the days of the process were taken from this very balcony.

The stage was not immobile: the stenographers changed every 25 minutes; the task of their service was to prepare a complete transcript of the meeting in four languages by the end of the day. Each place was radio-ready – the speakers' speeches could be listened to in any of the four languages.

Richard Sonnenfeldt, the translator for the American prosecution, describes in his book how, many years later, he happened to find himself in the role of a guide in Courtroom 600: “Every detail of the [HP1] 1945 courtroom was etched in my memory, but now the room’s layout was different <...> I pointed to the spot where Justice Jackson stood (Robert Jackson, Chief United States Prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials of Nazi war criminals following World War II, and later a member of the US Supreme Court – Author) as he said: ‘We must also be prepared that this court may find some of the defendants not guilty. Otherwise we might just as well hang them all now!’”

Just Stare at Them and Look

The public’s attention was focused on the defendants. First and foremost, on Hermann Goering. “Goering was very confident and, I would say, arrogant”, Boris Yefimov, a caricaturist, recalled in one of his public speeches, and whose drawings accompanied almost every publication of the newspaper Izvestia in Nuremberg. “It was as if it was written on his plump crimson face - look first of all at me, I am the central face of the process here. And really, in Germany, he was number two after Hitler, and here he was number one. And, apparently, he just liked it, he was flattered by this attention. He was even accompanied by a separate American policeman, who, unlike the others standing behind the defendants, stood with his back to the courtroom, facing him with a baton. And, of course, it was a pleasure to come out and approach the barrier like somewhere in a terrarium or a menagerie when you look at some python or tiger. Staring at it like this and looking at it from an arm’s length away. At first, he pretended not to pay attention, then began to look askew and, finally, turned away angrily, and it was written on his face: ‘If I had caught you a year ago – I’d have shown you!’”

There was a man in Nuremberg who could approach the defendants at any distance and ask any question. That was an American forensic psychologist Gustave Gilbert. “By the first days of the trials, I noticed that a young American officer with an ISO armband (Internal Security Office – Author) often talks to the defendants”, Arkady Poltorak writes. “In Nuremberg, journalists all over the world envied this man. He had the opportunity to communicate with the defendants at any time without any restrictions, both in the courtroom and in prison cells, both publicly and in private <...> He knew many things that others did not know. Journalists were literally after him, hoping to find something sensational for the press”.

Gilbert kept secrets as long as required by law, and then published his diary in a separate book. This is how he describes the first public session of the process:

“When the defendants understood that the opening of the court session included only a reading of the indictment, which they had already become acquainted with, the tension on the defendant's bench decreased significantly. They sat indifferently and motionlessly, some of them used headphones to plug in different translation languages one by one, some of them looked at those present in the courtroom: judges, prosecutors, reporters, and the public”.

Goering: It Was Hidden From Us!

Perhaps, the first day even gave the defendants some pleasure. “The break”, continues Gilbert, “At the first meeting, the defendants gave free rein to their feelings – they shook hands, talked to each other for the first time since the arrest <...> After the courtroom was empty, they stayed there and chatted with a sense of relief on topics ranging from politics to natural issues. Ribbentrop tried to talk to Hess, but it did not work out, because Hess could not remember any of the charges listed in the indictment”.

Cynical Baldur Schirach made a joke during lunch: “Probably the day we get hanged we'll have some steak”.

Julius Streicher succumbed to nostalgia: “You know, Herr Doctor, <...> I was already sentenced once in this room. - Really? How many times have you been put on trial? - Oh, about twelve or thirteen times. So, I have more than one trial behind me. Not my first time”. It should be made clear that the leading anti-Semite of the Reich was tried for corruption at least once.

Ribbentrop said: “You'll see, a few years later lawyers will denounce this trial”. In the afternoon, as prosecutors from four countries took turns describing Nazi crimes, including atrocious killings, deportations for slave labour, and racial extermination, Ribbentrop got sick and was taken out of the room.

Hess stayed somewhere in his own little world. He whispered to Goering: “You'll see, this nightmare will fade away, and a month later you will again become the Fuhrer of Germany”.

“Defendant number one” himself held forth in the spirit of a Soviet film hero – your honours, of course, I am guilty, but it is not my fault. Gilbert quotes Goering’s words after the session: “For these crimes, the entire German nation is doomed to eternal damnation. But all these atrocities were so unbelievable – and even the little that became known to us – that it would have cost nothing to convince us that such charges were merely propaganda tricks. Himmler always had a fairly large choice of psychopaths ready to do this. And they were kept hidden from us”.

Blaming the two dead devils – Himmler and Hitler – would become the defendants' tradition.

Only Hans Frank stuck to the tactic of active repentance from the outset. “One can only think that we lived like kings and believed in this monster!”, he wept, talking to the psychologist, “And do not believe any of them, when they tell you that they knew nothing and did not have any idea! Everyone knew that everything was very, very wrong with this system, although they might not have known the details. They didn't want to know them! It was too tempting to suck on this system, to keep your families in luxury, believing that everything was okay! You still treat us fairly”, he added, nodding at the food on the table, which he never touched. “Your prisoners, and our compatriots, were starving to death in our camps. May God have mercy upon our souls!”

Frank and his accomplices had nothing else to rely on but the grace of God. Nuremberg justice had already drawn its sword over them.

By Yuliya Ignatieva