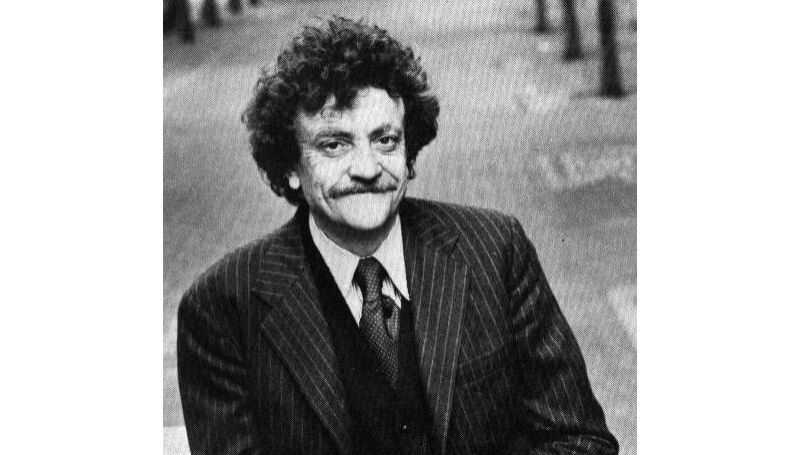

Airey Neave is the first representative of the tribunal seen by the criminal defendants.

At a hearing in Berlin on 18 October, the International Military Tribunal at the Nuremberg trials handed down an indictment. The document, translated into German and reproduced in the required number of copies, was sent to the prison at the Nuremberg Palace of Justice.

The defendants were given almost a month to read up on the charges. The first representative of the tribunal they happened to see was British Army major Airey Neave, who read the text of the indictment. He was a man with an incredible fate, from his youth until his death. When little more than a child, he predicted the consequences of Hitler’s party winning the German elections for Europe, and much later Neave was one of those who helped Margaret Thatcher reach the pinnacle of power.

From Cell to Cell

“So, Neave and I went to the cells of the Nuremberg prison”, writes the translator for the US prosecution team Richard Sonnenfeld. “[…] Colonel Burton Andrews, commandant of the Nuremberg prison, walked a bit behind us, holding his painted pistol in his hand, as two Russian officers walked with him […] We walked from cell to cell. The guard opened the doors one after another, and one by one the prisoners were taken to a small table […] While over the course many hours we read over and over a terrible list of crimes for each of the 21 prisoners, I again imagined heaps of corpses, feeling suffocated from the smell of the conveyor of death launched by these people and their accomplices […] The physical normality, the appearance of being a regular person from the street of these people, frightened me more than signs of insanity”.

Thirty-year-old Airey Neave came from an aristocratic family, was a qualified lawyer, fought in the artillery, and spoke German well. He was also an intelligence agent with Britain’s MI6. We do not know if MI6 was behind Neave being admitted to the tribunal staff. But he did not sit on his hands there. Among other things, Airey Neave prepared materials on the Krupp case.

Later, in one of his books, he would write that it took him twenty years to recover from the war, admitting to journalists that during those years he woke up in the middle of the night screaming. At the same time, his mannered reserve and unflappability ultimately cost him his life.

Camp Amateur Theatre

“The clock strikes, what the f**k, I have to run from the ball!”, Cinderella sang in a thick bass in an amateur operetta. The role of Cinderella was played by a mustachioed English officer, and the operetta was staged in a POW camp in Germany. That was the only hilarious episode in the anti-war novel Slaughterhouse Five, or the Children's Crusade written by the American veteran and former POW Kurt Vonnegut.

It’s difficult to say whether Vonnegut was ever a spectator of such a performance, but Airey Neave definitely was, and, perhaps, he himself even participated in the production. At the very least, his escape from a camp coincided with the time the play was on stage.

Airey Neave began preparing for war when he was a schoolboy. In 1933, the 16-year-old Eton pupil wrote a political essay dedicated to Hitler, Germany, and the future of Europe. His prophecies turned out to be very accurate.

Of course, there were shrewd young men at the time and we often see references to amazing predictions about World War II made by American, Soviet, and German teenagers. But Airey Neave didn't restrict himself to the role of Cassandra. Having entered Oxford, he bought and read everything written by Carl von Clausewitz, an early 19th century Prussian military leader and military theorist.

When asked why, Neave replied: “Since war [is] coming, it [is] only sensible to learn as much as possible about the art of waging it”.

He did not fight for long, just from February to May 1940. Wounded in France, he was taken prisoner in Germany. A year later, he made his first escape attempt and it proved to be unsuccessful. Neave along with his friend escaped from the camp and wanted to reach eastern Poland, which by that time had become western Byelorussia (part of the Soviet Union), but they were eventually captured and ended up in the hands of the Gestapo, followed by Neave being sent to a very remarkable place.

Colditz Castle was one of the few exemplary POW camps, where the Germans strictly observed the requirements of The Hague and Geneva Conventions. The Red Cross supplied the Colditz prisoners with everything they needed and it was reported that the POWs’ food was better than that of the German guards, whose salaries in Reichsmarks did not keep up with the rise in prices.

The fashion for amateur performances was introduced by Polish officers, the camp’s first inmates. The musical genres that flourished in the camp included: a Polish choir, a Dutch ukulele ensemble, and a French orchestra. But in the art of drama, the British were the soloists, of course. Shakespeare was not staged, but Shaw was a great success. In order to play female roles, the inmates grew out their hair, one even shaved his legs, rubbed them with brown shoe polish, and drew a line on the back to imitate a stocking seam.

From Captivity to Intelligence

And yet it was a camp, with a tough regime and all the delights of Nazi management. Its "actors” were captured officers whose duty was not to have fun in an amateur theatre, but to escape and return to the front. Escaping Colditz was no easy task though. The camp was located in a medieval castle on a cliff near the Milda River. There were so many attempts by POWs to escape that the guards even set up a museum with the devices they seized.

Planning escapes became a constant occupation of the prisoners. To prevent prisoners from different national communities from accidentally disrupting each other's plans, coordinators were appointed. They knew everything about the latest plans to escape, but they themselves had no right to leave the camp. Almost all attempts ended in failure. Discovering that someone was missing, the camp administration immediately notified the local population of this, and the more than obliging guys from the Hitler Youth organisation (Hitlerjugend) quickly caught the fugitives.

Airey Neave staged his escape a couple of months after he arrived in Colditz. He and his accomplice, a Dutch officer, were able to get out of the castle only to be finally detained. It was Neave’s homemade uniform put together from a Polish officer’s kit and painted in a “German” colour with the help of a gouache that gave him away.

Six months later, on 5 January 1942, Neave and another Dutchman managed to outwit the guards. As it turned out during an amateur theatre performance. The accomplices fled through a hatch in the floor of the stage, left the castle, and even boarded a train to Switzerland. Then, Neave returned to his homeland via France, Spain, and Gibraltar. He became the first Briton to escape Colditz. During the camp’s six-year existence, just fifty of its several thousand POWs managed to escape.

At home, Neave immediately "found a job according to the specialisation” he received in captivity, namely, with the MI9 intelligence service. The latter was tasked with organising the escape of British POWs. MI9 aided the escape of about 5,000 Britons and Americans, not including the 300 pilots shot down in the skies over France and Belgium and hidden by partisans. During this period, Airey Neave was recruited by the intelligence service MI6 and given the codename “Saturday”.

Margaret Thatcher’s Tender Friend

With the war behind him, Airy Neave began writing books. There are five of them, and one is entirely dedicated to the Nuremberg trials. This book has been reprinted many times, and all English-speaking readers who are interested in the history of the international tribunal know it. The book, however, has not yet been translated into Russian.

Literary creativity became Neave’s main hobby, but politics was his profession. A Tory supporter, he was elected to the House of Commons from the Conservative Party, where he met his political idol, future Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. Neave was a war hero and celebrity, while Thatcher, from the point of view of her opponents, was a “desperate housewife”, something that, however, didn’t stop Neave from trusting her. On the eve of the 1974 party elections, he proposed his candidacy for Thatcher's chief of staff. She won and took over the party, which at that time was in the opposition. In return, Thatcher offered Neave any position in her shadow cabinet. He wanted to become Minister for Northern Ireland, seen at the time as the most thankless and dangerous job, given the deterioration of the Irish issue.

He did not have a chance to "come out of the shadows” and sit in a real ministerial chair because a couple of months ahead of the general parliamentary elections, in which Thatcher and her party prevailed, Airey Neave perished.

A bomb exploded in his car on 30 March 1979, when the politician was driving out of the parking lot at Westminster Palace. The 63-year-old lost both legs and died an hour later in hospital. The Irish National Liberation Army (INLA), an armed group that had broken away from the Irish Republican Army (IRA), claimed responsibility for the attack.

Speaking at a mourning ceremony, Margaret Thatcher touted her associate as “one of freedom’s warriors”.

“He was one of freedom's warriors. No one knew of the great man he was, except those nearest to him. He was staunch, brave, true, strong; but he was very gentle and kind and loyal. It's a rare combination of qualities. There's no one else who can quite fill them. I, and so many other people, owe so much to him and now we must carry on for the things he fought for and not let the people who got him triumph”, Thatcher said.

Airey Neave was also a fatalist. He was offered protection as police warned him that his life was in danger. Neave, however, defied the warnings, saying that INLA militants were cowards and would not be able to meet him face to face.

The INLA also commented on the death of its enemy, publishing a statement in the press saying “In March, retired terrorist and supporter of capital punishment, Airey Neave, got a taste of his own medicine when an INLA unit pulled off the operation of the decade and blew him to bits inside the 'impregnable' Palace of Westminster. The nauseous Margaret Thatcher snivelled on television that he was an 'incalculable loss'— and so he was— to the British ruling class”. [HP3] The INLA were outlawed by the UK government over Neave's assassination.

Shortly after his death, speculation emerged that Neave’s murder was actually the result of a joint operation conducted by the INLA, the CIA, and MI6. Media reports claimed that intelligence killed their own agent because he was ostensibly collecting material about corruption in the agency. In March 2019, exactly 40 years after Neave’s death, Scotland Yard resumed its investigation into his murder.