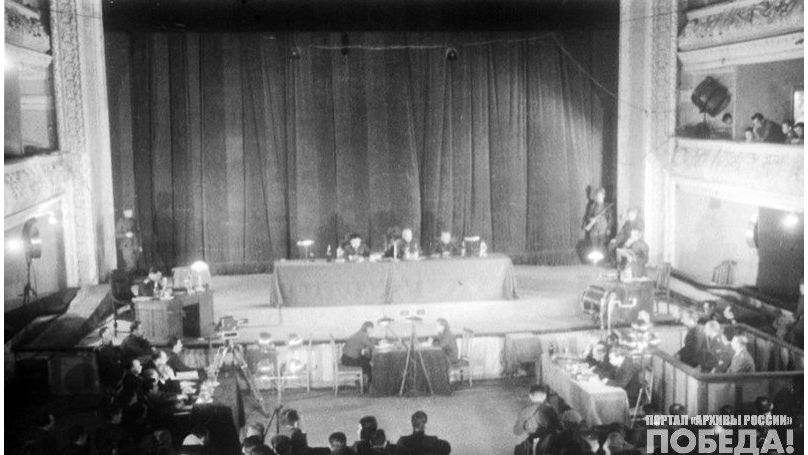

The Nuremberg Tribunal was also known by its nickname "The Trial of Six Million Words" because of the sheer number of column inches that were published about it. By now, of course, a good deal more than six million words have been written about the event, what with all the histories that have been written. But at the time, between November 1945 and October 1946, there were 315 journalists and writers from 31 countries covering the moment when a whole cast of murdering fascist criminals were brought to justice, filing thousands of articles and essays while the army of photographers who were present at the tribunal took at least 25,000 pictures and made several dozen films.

“On a cold, grey and foggy morning in November 1945 two Dakota aircrafts took off from the Central airfield in Moscow, heading west,” Daniel Kraminov, the head of the TASS News Agency’s Berlin desk recalled. “Already old, somewhat old-fashioned but warmly dressed people were sitting on hard metal benches along the walls with rare round windows. Their names, recorded by the flight attendant on the passenger lists, were well known within the Soviet Union and abroad”.

They were famous cartoonists, filmmakers, cameramen and war correspondents. They all flew to Nuremberg: the USSR’s press contingent at the international tribunal numbered an incredible 45 people and that wasn’t including such prominent writers as Vsevolod Vishnevsky, Leonid Leonov, Konstantin Fedin, Vsevolod Ivanov, Semyon Kirsanov and Yuri Yanovsky. The pencils of the Soviet Union’s best journalists were sharp and their aim was to show the world what a vital purpose vengeance in Nuremberg served.

Death for Death!

The idea that the very best writers should be employed to convey to their readers the wickedness wrought by the Nazis was nothing new. In the summer of 1942, long before the tribunal had even been thought of, President Theodore Roosevelt’s associate Harry Hopkins proposed the creation of an informal International Commission of eminent authorities. Julio Alvarez del Vayo, a publicist and socialist who had fled into exile from the Franco regime, represented Spain. Count Carlo Sforza - a diplomat and anti-fascist, and Italy’s future foreign minister - was to participate on behalf of Italy. Russia was to be represented by Alexey Tolstoy, nicknamed “the Comrade Count”, who, despite being a count fit into the Soviet higher circles and even won three Stalin prizes of the first degree.

It is significant that it was Tolstoy who took part in the world’s first open trial of Nazi criminals, which took place in December 1943 in Kharkov.

That process not only set a legal precedent, but also established the principles according to which such tribunals were subsequently covered. Besides the Soviet press, reporters from such newspapers as the New York Times, the Times and the Daily Express attended the trial in Kharkov.

“In 1945 there was an idea to make a film about Tolstoy,” the poet Valentin Berestov recalled, “and Alexey Nikolayevich was depicted as a member of the Extraordinary Commission for the Investigation of Fascist Crimes. Then, when fascism retreated its monstrous and scary footprints were revealed. The world prepared the charges later brought against the Nazis at the Nuremberg trial.”

After Tolstoy’s death in February 1945, Ilya Ehrenburg was the most famous published author. Ehrenburg, arguably the greatest master of anti-Nazi propaganda, had achieved great fame as a war correspondent during the Spanish Civil War and returned to the USSR only when the Nazis had occupied Paris. Ehrenburg was offered a column on the Krasnaya Zvezda (“Red Army newspaper”) and wrote more than 2,000 articles during the war years as well as a pamphlet entitled “Kill” in which he wrote: “The Germans are not humans… If you do not kill the German, he will kill you…. Kill the German, thus cries your homeland.” His work during the war years cannot be overestimated - newspapers containing his articles were read so many times that they often ended up falling to pieces and Hitler inadvertently paid him the ultimate compliment when he called Ehrenburg the worst enemy of Germany. At the end of the war, official Soviet propaganda brought him under control lest his rhetoric be considered incitement to hatred of the Germans.

The worst enemy of Germany

The tribunal started on 20 November 1945. At this time Ehrenburg was in Europe, from where he sent his “Letters from Yugoslavia” to the soviet newspaper Izvestia (The News). After being invited to Nuremberg, Ehrenburg, who was in his fifties, decided to buy a new coat, which proved a problem in post-war Belgrade. However, one Jewish shopkeeper who had miraculously survived learnt about what Ehrenburg wanted and said: “Three mule skinners have escaped death. If Ilya Erenburg goes to the trial of the bloodsuckers, we will get him a coat even if it kills us. Let them see that we can sew. You must tell them that they all must be hanged...” Thus, the writer arrived in Nuremberg wearing a luxurious short fur coat.

By that time, the Soviet side had already exceeded its limit of how many reporters it was permitted to take, but Ehrenburg threatened: “I will immediately leave and then let it be known that Ehrenburg was not allowed to the trial of Hitler`s criminals.” An entry-pass was thus found.

This obviously goes to show how celebrated a writer Ehrenburg was - in fact, he was so famous that he couldn’t even walk freely through the corridors of the court as people constantly surrounded him. The defendants recognised him as well - the cartoonist Boris Yefimov recalled: “The appearance of this silver-haired and slightly hunched man in a brown loden suit with numerous medals on his chest could not go unnoticed... I saw Rosenberg giving him a dark look as he entered, Keitel, who turned his arrogant face away, and even Göring looking at Ehrenburg with his droopy, bloodshot eyes”.

In Nuremberg, Ehrenburg wrote two essays, and they are almost a distillation of what the tribunal represented: on the one hand, unspeakable crimes and loathing for the perpetrators and on the other, belief in the triumph of humanity and faith that after the tears and sorrows of the fascist regime, good would prevail. Ehrenburg managed to seek out the moral of history: “As for the personalities of the defendants,” he wrote, “what can be said? Before us we see small villains who have committed the worst atrocities. Each one of them is mentally and intellectually worthless. Looking at the dock, you ask yourself: how could these evil and cowardly bastards lay waste Europe, killing tens of millions of people? However, to create something one needs to be a genius, whereas to destroy something… well, any idiot could have killed Pushkin, and every savage could have burnt Tolstoy’s books. The criminals will be hanged: conscience demands it. But not only will the fascists be convicted – the very idea of fascism will be condemned. Those who created it and those who wish its revival, its progenitor and its successors will be denounced. The peoples have suffered too much grief, and now they are keeping their eyes on Nuremberg. Here is an old Montenegrin woman whose children were burnt by the Germans, the friends of Gabriel Peri, and that lady from Mariupol who told me that when her daughter was undressed by the Germans, she cried: ‘Uncle, it’s so cold, I do not want to swim’, but ‘uncle’ buried her alive; here is the widow of a Russian soldier, here are the children of Lidice, here are all of them, they are all my loved ones, my friends, all who have a heart, and they all say: ‘Remove the fascists from the world! Take away fascist stink from our heads and our souls. Let the wheat and children, cities and poetry revive, and let life live! Death to death!” (Izvestia, 1 December 1945).

Nothing has been forgotten

Stalin himself approved a list of 24 Soviet journalists to be sent to Nuremberg. Then the Soviet corps was expanded to 45 people because of competition between the Sovinform Bureau and TASS, and to keep up with the US-UK coverage of the international tribunal. Publications about the process in the newspaper Izvestia were accompanied by a series of caricatures by Boris Yefimov entitled “Fascist menagerie”. The delegation included three famous cartoonists known collectively as "Kukryniksy" - Mikhail Kupriyanov, Porfiri Krylov and Nikolai Sokolov.

Of course, the “members with notebooks” were quite different at the Nuremberg Tribunal: they all had different talents, temperaments, and, after all, levels of seniority. But what they all had in common was a frontline view of history in the making and personal confidence in the justice of retribution. Both high-skilled professionals and ordinary reporters worked as military correspondents: Boris Polevoy, who had five combat orders, and David Zaslavsky worked alongside Mikhail Dolgopolov who, because he one of the oldest in the press pack in Nuremberg, was nicknamed «Papa», and who used to write about the circus in peace time. These all rubbed shoulders with lieutenant-colonel Yuri Korolkov, Vasily Velichko, Viktor Shesterikov and many others.

At the beginning of the trial, they were overwhelmed by how peaceful and ordinary the defendants were. “Once I spoke with Vsevolod Ivanov in a cold corridor,” Boris Polevoy, who wrote a lot of essays about the tribunal, recalled. “Being very confused he asked me: ‘What does it all mean?’ I replied ‘I don’t know’. The procedure itself was not difficult for the judges to understand - the crime was clear - whereas we, the writers, wanted to understand, how these people could do all the things they were talking about, and how could other people follow their orders unconditionally? We tried to understand, but we could not... It seemed to be nothing but bloody accounting”. The term “banality of evil” appeared only years later.

But the evidence of the Nazi crimes presented at the tribunal, made even those who had seen a lot lose sleep. The same Boris Polevoy wrote that after Göring’s interrogation, there was only one way he could ameliorate the depravity which had been related. The forced words of the “number two Nazi” of Germany and the “loyal soldier of Hitler” about the “mysterious” Soviet man, whom bourgeois Europe could not understand, brought to mind his acquaintance from the front, fighter pilot Alexei Maresyev. Polevoy wrote “The Story of a Real Man” in 12 days - Nuremberg had turned this essayist into an acclaimed novelist.

«Khaldeiniks» and «kurafeys»

According to the slang of the time, Boris Polevoy went from being a “Khaldeinik” to being a “kurafey”. Journalists were billeted according to their status - prominent authors had rooms in the Grand Hotel, and the ordinary lot were stationed in the press-camp at the Faberschloss which was also known as the “Castle of Horror” because of the bad taste in which it was decorated. Therefore those at the hotel, according to memoirs, were nicknamed “kurafeyniks”, and those in the press-camp “khaldeiniks” since the photo journalist, Captain Yevgeny Khaldei was among the guests at the Faberschloss.

But history is a great leveller: Konstantin Fedin, lived in kurafey of course (he had a car accident in Berlin, and reached Nuremberg only by mid-January).

As a young man he had earned a living playing the violin in Khaldeinik, which was then a restaurant. Fedin left Nuremberg at the start of the First World War in 1914 and returned more than 30 years later, after the horrific events of another war. His tribunal writings must be the most poetic. The criminals were “sculpted” in his novels, witnesses to the prosecution and ex-prisoners of Mauthausen and Auschwitz “called for revenge from the height of the last step”. The author wrote: “When I look into the dock, it seems to be a broken barge, with half-dead pirates on its board. It’s falling apart. There’s no gear left on it, no lifeline, and no solid fragment. Rough waves washed it all away. But the hands grasping at the board are fitfully strong in the last moment. (...) For years they rampaged through the boundless open waters of the globe. Their crews travelled far from the German coasts to the Atlantic and the Barents Sea, the Indian and the Pacific Oceans. They sought to dominate ruthlessly wherever human race sailed. Wherever their steel submarines-boats reached, the clear blue water of the seas turned muddy from human blood.” (Izvestia, 25 January 1946).

In contrast, Leonid Leonov, who became a court chronicler after the Kharkov trial, was rather fierce. His words also rang out throughout the world: in 1942 Leonov wrote two letters to and “Unknown American Friend” - a reminder of the responsibility all countries have for the fate of mankind and about the need to open a second front. The letters were broadcast by the largest radio stations in the United States. By the mid-Forties, Leonov’s novels were being translated in the US.

An essay “Gnomes of Science” about experiments conducted on prisoners of Dachau by the “finest minds” of Nazi medicine: “It seems to me that degradation of every civilisation begins with the decline in national moral standards. In a thousand years, were there many attempts of the West to wash and clean the old, run-down waters of its culture? Good deeds of civilisation become a human curse when they are not guided by the dream of human happiness. Otherwise, the history brings a civilisation to its mainstream, and a miserable and mangy beast eats whatever it finds until it is angrily beaten by someone with a stick in the alley. I bow my head in respect to all doctors of my country, who rejoice with sincerity when they take in their arms the small body of a new citizen of the universe or who grieve with an open heart when death steals its prey from their hands. I think of our simple village doctor (...), who sometimes has nothing but excellent skill and knowledge about the human body as his only tool. He sees a man not as a rabbit, as these gnomes from Dachau did, but as a free maker of bread, creator of songs and machines. Only a living creature can truly appreciate life. Therefore, the unknown doctor somewhere in the tiny town of Chistopol on the Kama river seems to me - from the campus of Nuremberg - the greatest humanist in the world”. (“Pravda”, 22 December 1945)

From pathos to pamphlet

However, Vsevolod Vishnevsky, who wrote more than 20 essays in Nuremberg, was the loudest Soviet voice among the tribunal’s numerous voices. The captain of the 1st rank, who earnt his first awards in the First World War, already responded even to congratulations in a military way: “I serve the Soviet Union!”. Vishnevsky considered “scientific, systematic analysis of National-Socialism - modern capitalism in German form” to be his task. His essays were truly pathetic: “Nothing has been forgotten”, “The plan of the criminals sitting on the dock was recklessly ambitious: ‘Germany is Europe, Germany is the globe’, they said. They wanted to command all mankind, turn it as they wished, and train it in the light of German torches and in the roar of Prussian orchestras. They wanted to line up all nations and appoint their own Reichsleiters. (...) Yes, it was all there. And let us never forget. Let our common sense, our unshakeable faith in peace, in love and friendship, in the fraternal basis of human labour, in the common progress help us once and forever remove the nightmare of fascism from this world.” (Pravda, 16 December 1945).

However, besides the high style of Vishnevsky, there were very different lines - even pamphlets - sent to Moscow. Their author was the polemicist Semyon Narignani, who became so prominent after the war that Raikin (the soviet comedian) quoted him in his monologues. In the corridors of the tribunal, Narignani became famous for a joke: “Göring looks rather wrinkled today. It's all right, he will be smoothed out when hanged”.

But such a voice was necessary. “As for former Nazi ladies, according to local newspapers, bored Nuremburg frau are mainly engaged in looking for love in the lonely hearts(...) ‘Fraulein aged 35, height 172 cm and weight 84 kg, comfortable, is looking for a companion for life. Preference will be given to a victim of Nazism or a Jew”. “Göring and Streicher have not been hanged yet, and the Golden-haired Nazis are already thinking of a better way to adapt to the new conditions.”

“The Nuremberg trial has been somewhat dragged on. (...) The delay also creates some strange illusions for the defendants. Some of them continue to hope for something. Dönitz and Raeder are sitting in dark glasses. The Grand Admirals are keeping their eyes off the electric light. Göring is wrapped up in a prison blanket: the sentenced to death is afraid to catch a cold. Frank shaves twice a day, he gets ready for the tribunal`s sessions as for a job. (...) The routine is not onerous at all. But still Rosenberg looks down on the judges if the evening session should happen to end five minutes late. The philosopher of racism looks at the clock and thinks time works for him. Alas! There are also clocks on the wall, above the dock. He`d better look at them. They’re counting down the last few minutes of the criminals` life”.

Their customs

The tribunal operated for 10 long months. In the Soviet press the topic was extremely popular: Western journalists, after they had written about the first sessions, were fading away without sensation. And when the bell rang in the Palace of Justice, heralding unprecedented news, they knocked each other down. The film director Roman Karmen said: ”American correspondents have a very interesting writing system. Our system is the following: we leave the courtroom, then Vishnevsky, Polevoy or Vsevolod Ivanov write a report. (...) The American correspondent grabs something: ‘The defence counsel of Göring demands this and that... the Tribunal refused him…’. He makes up the story already in telegraphic form. A courier immediately comes to him quietly and delivers a paper to the telegraph”.

On the one hand, Soviet writers denied the hunt for “hot” news, especially since sometimes the world press “put up a yarn in Nuremberg” (Narignani). For instance, the American newspaper «Stars and Stripes» reported that the Soviet prosecutor General Rudenko tried to shoot Hermann Göring. Or that 20,000 SS men who escaped from the Dachau camp are on their way to Nuremberg to free Göring from prison. On the other hand, soviet journalists faced competition as well and started thinking.

The western press was not monolithic, and newspaper politics was different. But many of the western journalists were pro-Soviet. For example Ralph Parker, who worked in Moscow and later turned out to be a double agent and remained in the USSR. Czech prose Jan Drda and Polish Edmund Osmańczyk are other examples. The Norwegian journalist Willy Brandt worked as a correspondent as well, later in 1969 he became German Chancellor, knelt down in Poland in 1970 in front of the monument to the heroes and victims of the Warsaw Ghetto. Each day journalists sent as much as 120,000 words to their agencies, which were then published as articles and news all around the world.

Walter Cronkite was the first correspondent of the United Press International, who later became a legendary CBS evening news host and commanded the trust of millions of Americans. The Nuremberg trial was covered by Marquis William Childs and Eugene Davidson, who wrote in his book The trial of the Germans: “The defendants behaved as people who have woken up from a fantastic dream in which they played imagined roles; now they find themselves in the real world, rejecting Nazism, in which killing of innocent people is always punishable, and they look on their own atrocities with distrust and horror”.

There were, however, other trends. As Andrew Nagorski later noted in his book The Nazi Hunters: “Prominent journalists, among whom were such stars as William Shirer, Walter Lippmann and John Dos Passos, were initially rather skeptical: “All this is just a show, it will not last long, and they will all be hanged soon”. Meanwhile, in the United States, the drama unfolding in the courtroom not only aroused mistrust, but also provoked the opposition. Milton Meyer wrote in his column in the Progressive magazine: “Vengeance will not bring killed people back from their graves”, stating that “the evidence obtained from the liberated concentration camps in the usual legal practice would not be enough for accusations of such a scale”. While the critic from the “Nation” journal James Agee even claimed that “the documentary about Dachau shown in the courtroom was a propaganda exaggeration”.

Human soul engineers

Both European and American writers attended the tribunal as well. For example, Thomas Mann’s eldest daughter, Erika Mann, German comedian, journalist and author of children’s books, and Guards captain Richard Llewellyn, author of the 1939 novel “How green was my valley” were among the visitors to the Palace of Justice. People as diverse as the Argentine intellectual and feminist Victoria Ocampo, famous for her novels dedicated to Igor Stravinsky, Jorge Luis Borges and Graham Greene attended the trial as well as the Englishwoman, Gitta Sereny, who was described as a woman who tried to humanise monsters. Born in 1921 in Vienna, she became interested in Nazism at an early age, and after meeting Hitler's architect Albert Speer in Nuremberg, she published his biography. She also wrote a book about the Commandant of Sobibor and Treblinka Franz Stangle. Ernest Hemingway attended several sessions as well.

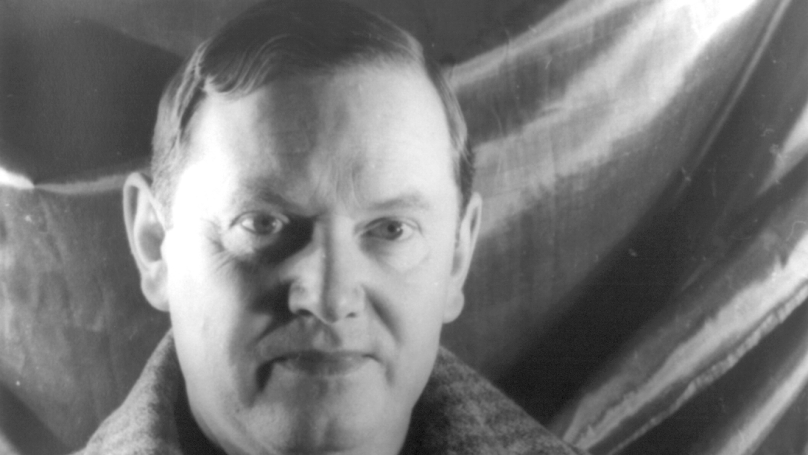

Between 31 March and 3 April 1946 an extremely august guest graced the tribunal with his presence - the British author Evelyn Waugh, whose novel Brideshead Revisited is in the list of 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century. During the war he served in the Marine Corps and participated in the amphibious operation in Libya, received the rank of Captain, was in Yugoslavia in 1944 with a special mission. His letter to Sir Winston Churchill’s son Randolph was published:

“Notes on Nuremberg. Surrealist spectacle. Two buildings standing – a luxury hotel and luxury law-courts – amid acres of corpse-scented rubble. Kaiser Wilhelm baroque hall, functional light, functional furniture, a continuous parrot-house chatter of interpreters. Interpretation almost simultaneous. Curious sensation of seeing two big men bullyragging and their voices coming through the head phones in piping female tones with an American accent. Obvious irony of Russian bullet-headed automata sitting on judges bench. Russian delegation all in top boots epaulets, everyone else in plain clothes. Russians sit immobile listening hard, quite bemused, as strange as renaissance Venetian ambassadors at the court of Persia. (…) Göring has much of Tito’s matronly appeal. Ribbentrop was like a seedy schoolmaster being ragged. He knows he doesn’t know the lesson and he knows the boys know. He has just worked out the sum wrong on the blackboard and is being heckled. He has lost his job but has pathetic hope that if he can hold out to the end of term he may get a ‘character’ to another worse school. He lies quite instinctively and without motive on quite unimportant points (...). Surprising esprit de corps among English lawyers. They are not at all blasé. Working very hard and believing their work historically important.”

Well, there’s a reason Waugh is known as a great satirist. At the end of the letter he writes: “Please do not quote me in any sense which would seem to show me ungrateful to my hosts or skeptical of their good work. In fact please do not quote me at all.”

Maybe the attitude of the authors to the tribunal depended on how they experienced the war. The jaded Waugh was focused on details, remained skeptical and ironic whereas Hans Fallada, almost destroyed after living in Nazi Germany, tried to figure out how to live on. Konstantin Fedin recalled: “Being nervous and painfully impatient, he spoke rather abruptly, suddenly asking questions: ordinary Germans must know: What`s next? They were indifferent to the Nuremberg trials; they feared that they would be fooled again. They hate their past and do not see a clear future.”

French author Raymond Cartier wrote the book The Secrets of War on the materials of the Nuremberg trial and stated: “The trial of the criminals was a trial over the whole regime, an entire era, over the whole country.” The poet Semyon Kirsanov in his reports for the Trud (Labor) newspaper admitted that there were no sufficient ways to depict the past: “The artist as gifted as Dore, a poet with as great a genius as Dante, who could reveal to the world the monstrous image of the Earth conquered by Hitler, has not yet been born. Dachau and Auschwitz camps were only the drafts of German plans.Hiter`s universe would know the only law - the fantasy of the cold-blooded monster.”

By Yunna Chuprinina