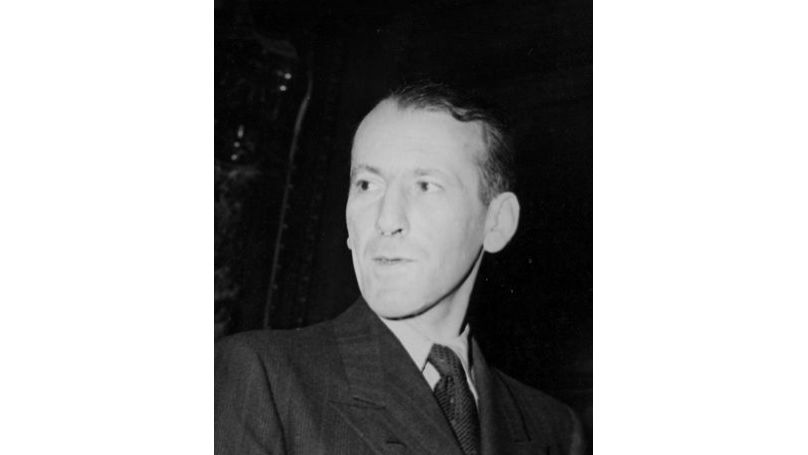

The cross-examination of Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Chief of the Reichsicherheitshauptamt (the RHSA or Reich Main Security Office), is perhaps the best example of the devious lengths to which the Nuremberg defendants were prepared to go to squirm their way into escaping justice. The head of the Reich's secret services swore that he either did not know about the atrocities committed by his subordinates or could not influence them. He dismissed the plethora of witness statements as lies, his own signatures on criminal orders as forgeries, and he portrayed himself as a democrat and human rights activist who was not afraid to question orders - even those of the Führer.

This text has hardly been seen by Russian-speaking audiences until recently. Only small fragments have been translated and many phrases from the interrogation that took place between 11 and 13 April have been cut out. Today, the “Nuremberg: Casus Pacis” project presents the first media publication of Kaltenbrunner's most revealing dialogues with prosecutors and his defence counsel.

Commentary by lawyer, international law scholar and translator of Nuremberg Trials Stenograph, Sergey Miroshnichenko:

Kaltenbrunner, who took over as head of the RSHA in January 1943 - a time when the German military successes were in decline - presented himself at the trials as an active opponent of his fellow Austrian Hitler and the Nazi extermination machine, and claimed to have been unaware of the Nazi crimes until a certain point.

Unlike the other defendants, he vigorously denounced the Nazi regime, admitted knowledge of Jewish extermination and revealed details of his negotiations with the Americans at the end of the war. Kaltenbrunner explained his rise to the position of the second man in the security services by the need to introduce the “democratic spirit” of Austria into the Reich's security system. In fact, Kaltenbrunner was probably brought in because, as a relatively new person, he could serve as a link between the Nazi leadership and the countries of the West.

When Kaltenbrunner spoke of a “new criminal law”, which he called flawed, he was referring to amendments to the German Penal Code of 1872. They were adopted in 1933 and introduced a new type of punishment – “protective custody”, a euphemism for sending “suspicious persons” to concentration camps without trial or even a charge. At the Nuremberg Trials, the internment of people in concentration camps under the “protective custody” orders was imputed to the defendants as part of a conspiracy to prepare a war of aggression.

Kaltenbrunner also claimed that he did not sign criminal orders: this was allegedly done on his behalf by his subordinates in accordance to previous practice (the idea that Kaltenbrunner’s predecessor at the RHSA, Reinhard Heydrich, a man known to be extremely tough, had delegated signing documents to his inferiors is utterly absurd). At the same time, Rudolf Höss, former commandant of Auschwitz concentration and extermination camp, testified at the Nuremberg Trials that he had seen several execution orders for prisoners with Kaltenbrunner’s authentic signature.

Did Kaltenbrunner Have Real Power?

To begin with, I would like to state that I assume responsibility for every wrong that was committed within the scope of this office since I was appointed chief of the RSHA and as far as it happened under my actual control, which means that I knew about it or was required to know about it. (…)

[In December 1942] I explained to [Reichsführer-SS Heinrich] Himmler on which essential points I differed with National Socialism as to the home policy of the Reich, the foreign policy, the ideology, and the violations of law by the Government. I declared to him, specifically, that the administration in the Reich was too centralised; (…) I told him that the way it had been attempted to create a new German criminal law was wrong, and that German criminal law was casuistic. (…) I explained to him that the concepts of protective custody and of concentration camps were not approved of in Austria, and that every man in Austria wanted to be tried before a court of law.

I explained to him that anti-Semitism in Austria had developed in a completely different way and also needed a different handling (…) I also said that there was hardly any understanding in Austria of the fact that the Nuremberg Laws went beyond the Party programme in this respect. In Austria, since 1934, there had been a peaceful, regulated policy to allow the Jews to emigrate. Any personal or physical persecution of Jews was completely unnecessary(…)

I also told Himmler then that he knew very well that not only had I no training in police matters, but that all my activity up to then had been in political intelligence work, and that therefore, when taking over the Reich Security Main Office I not only refused to have anything to do with such departments as the Gestapo and the criminal police, but that the task to which he was appointing me - to set up and cultivate an intelligence service - would, in fact, be impeded by that. (…)

After the conference with Hitler in December 1942, he discharged me because I did not want to take over the Reich Security Main Office under the conditions with which the position had been offered, namely, that the executive departments should be managed by him as previously. He was so angry with me that he did not give me his hand and made me aware of his indignation in various ways during the following weeks(…) I assumed I was to get a post at the front because I had asked him for such a thing… but I was wrong. He told me:

“I have talked to the Führer and the Führer believes that the intelligence service needs to be centralised and reorganised. He will start the necessary negotiations with the Armed Forces, and you will have to organise and build up this intelligence service. It goes without saying that I, with [Gestapo chief Heinrich] Müller and [Criminal Police Chief Arthur] Nebe, will have direct charge of the executive offices.”

Why Would Kaltenbrunner Be Ignorant of Orders Bearing His Signature?

I am stating here emphatically that the such special assignments that had been given to Heydrich, as, for instance, the final solution to the Jewish problem, were not only unknown to me at the time but had not even been taken over by me(…)

I swear that not once in my life did I ever see or sign a single protective custody order(…) The signature “Kaltenbrunner” which can be seen on protective custody orders can only have come about because the office chief, Müller, signed my name on these protective custody orders - as he had signed for Heydrich when he was head of the RHSA - and he also instructed his sections, for instance, the protective custody section(…) Accordingly, quite obviously he continued to do so during my time because otherwise these orders could not have been put before me now. But he never told me of this and I never asked him to do it(…) he was immediately under - and had authority from - Himmler so that he just as well might have signed these documents “Himmler” or “By order of Himmler” or “For Himmler”. I admit that this remains a fact about which the Tribunal will not believe me, but nevertheless it was so(…)

Was Kaltenbrunner Involved In Creating Concentration Camps?

I did not establish any concentration camps in Austria which is where I was until 1943 and I did not establish a single concentration camp in the Reich from 1943 onwards. Every concentration camp in the Reich as I know today - and as has been proved here with certainty - was established on the orders of Himmler to Pohl. This also applies – and I wish to emphasise this – to the Mauthausen Camp, even though it is located in Austria. Not only were Austrian authorities not invited to establish the Mauthausen Camp, but they were horrified because, not only had Austria no notion of concentration camps, but there was no need to establish one anywhere in Austria(…)

I’ve already said that I never saw a gas chamber, either in operation or at any other time. I did not know that they existed at Mauthausen and testimony to the contrary is entirely wrong. I never set foot in the detention camp at Mauthausen - that is, the concentration camp proper. I was at Mauthausen, but in the labour camp, not in the detention camp(…)

Was Kaltenbrunner Involved in the Holocaust?

Immediately after Iearnt such a thing was going on, I fought, just as I had previously, not only against the final solution but also against this type of treatment of the Jewish problem. For that reason, I wanted to explain how I became acquainted with the whole Jewish problem, through my intelligence service, and what I did about it (…)

First, I protested to Hitler and, the next day, to Himmler. I did not only make my personal attitude clear and emphasise that such practices were against the ideas which I had brought over from Austria and my humanitarian beliefs, but immediately, from the first day, I ended practically every one of my situation reports right by saying that there was no hostile power that would negotiate with a Reich which had committed such atrocities. Those were the reports I sent to Himmler and Hitler, particularly pointing out also that the intelligence sector would have to create the atmosphere for discussions with the enemy(…)

I am firmly convinced that this is chiefly because of my intervention, although a number of others also worked toward the same end. But I do not think there was anyone who kept dinning it into Himmler or anyone who would have spoken so openly and frankly to Hitler as I did(…)

Dr Kurt Kauffmann [Defence Counsel for Ernst Kaltenbrunner]: Do you want to assume a responsibility in this connection or do you want to deny it?

Kaltenbrunner: I must deny it completely (…)

Could Kaltenbrunner Step Down as RSHA Chief?

Dr Kauffmann: I now come to the last question. I ask you whether it was possible that you - after you had become aware of what was going on in the Gestapo and concentration camps, et cetera - could have made any changes? If that had been possible, can you say that by staying on in your position you were able to make some improvements in conditions?

Kaltenbrunner: I repeatedly asked to join troops at the front, but the most burning question which I personally had to decide was: Will conditions thus be improved or will everything stay the same? Is it my personal duty to do everything required to change all these sharply criticised conditions?

Upon repeated refusals to my request to be sent to the front, I had no alternative other than to try to alter the system myself, the ideological and legal basis of which could not be altered by me, as had been proved by all the orders issued before my time and offered in evidence here. All I could do was to try to modify these methods while striving to have them abolished altogether.

Dr Kauffmann: Did your conscience permit you to remain in office in spite of it?

Kaltenbrunner: When I considered the possibility of exerting, again and again, influence on Hitler and Himmler and others, my conscience would not allow me to leave my position. I thought it my duty to take, personally, a stand against wrong.

Did Kaltenbrunner Visit the Mauthausen Concentration Camp?

Colonel John Harlan Amen, Associate Trial Counsel [chief interrogations division office for the United States Chief of Counsel in the Nuremberg trials]: I ask that the defendant be shown Document Number 3843-PS, which will be Exhibit Number USA-794. I would like to say to the Tribunal that there is rather objectionable language in this exhibit but I do feel that, in view of the charges against the defendant, it is my duty to read it nonetheless. (…)

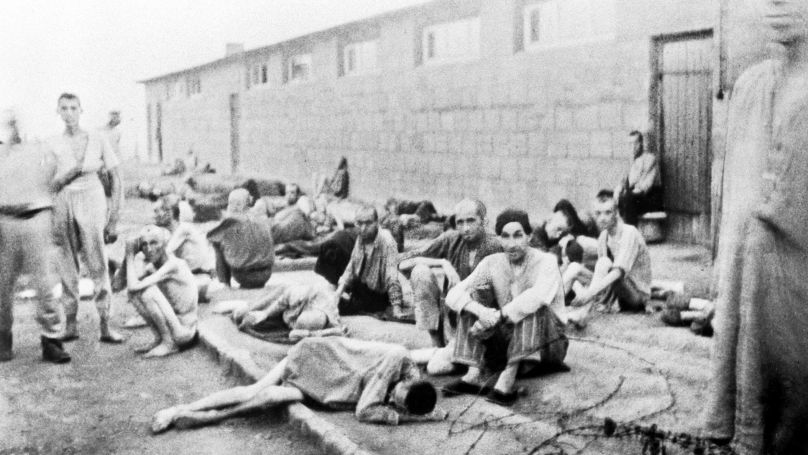

“I saw Kaltenbrunner again in the Mauthausen Camp, when I was severely ill and lying on the rotten straw with several hundred other seriously ill persons, many of them dying. The prisoners, suffering from hunger oedemata and from the most serious intestinal problems, were lying in unheated barracks in the dead of winter. The most primitive sanitary facilities were lacking. The toilets and the washrooms were unusable for months. Severely ill people had to relieve themselves in little marmalade buckets. The soiled straw was not renewed for weeks, so that a stinking liquid was formed, in which worms and maggots crawled around. There was no medical attendance or medicine. Conditions were such that 10 to 20 people died every night. Kaltenbrunner walked through the barracks with a brilliant suite of high-ranking SS functionaries, saw everything, must have seen everything. We were under the illusion that these inhuman conditions would now be changed, but they apparently met with Kaltenbrunner's approval for nothing happened after that.”

Is that true or false, Defendant? (…)

Kaltenbrunner: It is not true and I can refute each detail(…)

Col Amen: I ask that the defendant be shown Document Number 3845-PS, which will become Exhibit Number USA-795. (…)Do you know Tiefenbacher, Albert Tiefenbacher?

Kaltenbrunner: No.

Col Amen: If you have the document you will note that he was at Mauthausen Concentration Camp from 1938 until 1 May 1945 and that he was employed in the crematorium at Mauthausen for three years as a carrier of dead bodies(…) Now, passing to the lower half of the first page, you will find the question:

“Do you remember Eigruber?

Answer: Eigruber and Kaltenbrunner were from Linz.

Question: Did you ever see them in Mauthausen?

Answer: I saw Kaltenbrunner very often.

Question: How many times?

Answer: He came from time to time and went through the crematorium.

Question: About how many times?

Answer: Three or four times.

Question: On any occasion when he came through, did you hear him say anything to anybody?

Answer: When Kaltenbrunner arrived most prisoners had to disappear. Only certain people were introduced to him.”

Is that true or false?

Kaltenbrunner: That is completely incorrect.

Col Amen: Now I will show you the third document and then you can make a brief explanation. I ask that the defendant be shown Document Number 3846-PS which will become Exhibit Number USA-796(…) Are you acquainted with Johann Kanduth who makes this affidavit?

Kaltenbrunner: No.

Col Amen: You will note, from the affidavit, that he lived in Linz; that he was an inmate of the concentration camp at Mauthausen from 21 March 1939 until 5 May 1945; that besides work in the kitchen he also worked in the crematorium from 9 May, and he worked the heating for the cremation of the bodies. Now, if you will turn to the second page, at the top:

"Question: Have you ever seen Kaltenbrunner at Mauthausen on a visit at any time?

Answer: Yes.

Question: Do you remember when it was?

Answer: In 1942 and 1943.

Question: Can you be more exact, maybe the month?

Answer: I do not know the date.

Question: Do you only remember this one visit in the year 1942 or 1943?

Answer: I remember that Kaltenbrunner visited three times.

Question: What year?

Answer: Between 1942 and 1943.

Question: Tell us, in short, what did you think about these visits of Kaltenbrunner which you described? That is, what did you see, what did you do, and when did you see that he was or was not present at such executions?

Answer: Kaltenbrunner was accompanied by Eigruber, Schulz, Ziereis, Bachmeyer, Streitwieser, and some other people. Kaltenbrunner went laughing into the gas chamber. Then the people were brought from the bunker to be executed, and then all three kinds of executions - hanging, shooting in the back of the neck and gassing - were demonstrated. After the dust had settled we had to take away the bodies.”(…)

Kaltenbrunner: May I say something?

Col Amen: Is that true or false, Defendant?

Kaltenbrunner: Under my oath, I wish to state solemnly that not a single word of these statements is true. (…)

What Was the Meaning of the Phrase ‘Special Treatment’?

Col Amen: Defendant, you have heard evidence at this Trial about the meaning of the phrase “special treatment”, have you not? Have you heard that in this courtroom?

Kaltenbrunner: The expression "special treatment" has been used by my interrogators several times every day, yes.

Col Amen: You know what it means?

Kaltenbrunner: I can only assume - although I cannot be entirely accurate - that this was a death sentence, not imposed by a public court but by an order of Himmler’s(…)

Col Amen: Did you ever discuss with Gruppenführer Müller of Amt (Office) IV, applying the “special treatment” to certain individuals? “Yes” or “no”, please.

Kaltenbrunner: No; I know that the witness Schellenberg said…

Col Amen: I ask to have the defendant shown Document Number 3839-PS which will become Exhibit Number USA-799(…) Now let us read along in the centre of the page, commencing with:

“In regard to ‘special treatment’ I have the following knowledge:

On the occasion of meetings of the office chiefs, Gruppenführer Müller frequently consulted Kaltenbrunner as to whether this or that case should be specially treated or if ‘special treatment’ was to be considered. The following is an example of how the conversation went:

Müller: Case Obergruppenführer B. please, ‘special treatment’ or not?

Kaltenbrunner: Yes, or submit it to the Reichsführer SS for decision.

Or:

Müller: Obergruppenführer, no answer has arrived from the Reichsführer SS in regard to ‘special treatment’ for Case A.

Kaltenbrunner: Ask once more.

Or:

Müller handed a paper to Kaltenbrunner and asked for instructions, as described above.

When Müller had such a conversation with Kaltenbrunner, he only mentioned the initials, so that the persons present at the table never knew who was involved.”

And then the last two paragraphs:

“Both Müller and Kaltenbrunner proposed in my presence ‘special treatment’ or submission to the Reichsführer SS for approval of ‘special treatment’ for certain cases which I cannot specify in detail. I estimate that in approximately 50 percent of the cases ‘special treatment’ was approved.”

Are the contents of that affidavit true or false, Defendant?

Kaltenbrunner: The contents are not correct, when the document is given the interpretation you’re giving it. You will see immediately that the tragic expression “special treatment” is actually meant to be humorous here. Do you know what I’m talking about when I refer to the Winzerstube in Godesberg, or the Walzertraum in the Grosswalsertal (the Great Walser Valley), and their relation to the term “Sonderbehandlung”? Walzertraum is the smartest and most fashionable Alpine hotel of the whole German Reich, and the Winzerstube is a very famous hotel in Godesberg where many international meetings were held. Especially qualified and distinguished people have been kept there – for instance, Mr Poncet (the French ambassador to Berlin) and Mr Herriot and many more. They had three times the normal rations for diplomats, which is nine times the rations of ordinary Germans during the war. They were given a bottle of champagne every day and were allowed to contact their families in France freely and to receive parcels. These internees were frequently allowed to receive visits; their wishes were cared for wherever they were. That is what is meant here by “special treatment”.

Source:

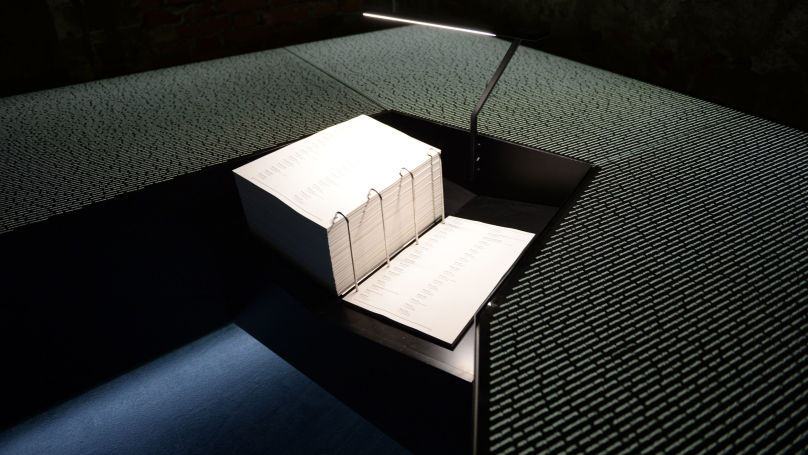

Nuremberg Trials Stenograph, Volume X (2021), Translated from English by Sergey Miroshnichenko.

We are grateful to Sergey Miroshnichenko, a lawyer and international law scholar, for his assistance in preparing the material.

By Daniil Sidorov