On 11 May 1987, the trial of the former head of the local Gestapo, Klaus Barbie, began in Lyon. France had been seeking his extradition for decades; but what the government failed to do, was accomplished by the husband and wife Serge and Beate Klarsfeld. They broke the stubbornness of the bureaucrats, the laziness of the judicial system, and exposed the lies of the intelligence services. The SS officer Barbier was brought to justice.

Paris, 1960s

The first thing he noticed when he saw the girl standing on the platform of the Paris subway was her thick blonde hair and piercing blue eyes. The Sorbonne student jumped into the train car following the slender girl and started a conversation with her. Hearing an accent, he asked: "You are not French, are you?" “I am a Berliner, I came to Paris to work as a governess, and I am also taking a secretary course”, she replied. After these two sentences, he invited her to the cinema.

“I couldn't let her just get off the train at her stop. Somehow I felt that this story would become important to me. But I could not imagine that this acquaintance would change my whole life”, he said later.

On the third date, Serge asked if the fact that he was a Jew scared her. "Why should this scare me?" “Because your countrymen killed six million European Jews”, he replied. “I don’t know anything about it”, Beate admitted. “My father was a Wehrmacht soldier, he was captured by the British. When he returned, we never talked about the war. And I was too young to remember anything except the bombing of Berlin at the very end of the war”.

And then Serge spoke about what he remembered. As an eight-year-old child, he hid with his mother in a closet behind a double wall, and when his father realised that the dog could find them, he went out to meet the Gestapo. That was the last time Serge saw his father - Arno Klarsfeld died in a concentration camp.

He also told her that he was looking for the names of those responsible for the death of not only his own father, but also numerous other fathers, brothers, mothers, sisters, and children. He said that the survivors were not waiting for revenge, but for justice.

“I can't be German anymore”, Serge heard after he finished his story. “You can’t give up your homeland or your language, but you can do something so that future generations of Germans can live without this shame”, he replied. “You can count on me, Serge. I will be with you forever".

That’s how the love story of Beate and Serge Klarsfeld, as well as their life together, began.

After the Nuremberg trials, life in Europe gradually went back to normal. Cities were rebuilt, the economy was gaining momentum, every day there were fewer ruins and more money. The nightmare had ended. The Klarsfelds were one of the few who refused to forget the past. Prosecutor Fritz Bauer, who played an essential role in starting the trial of the guards at Auschwitz, said “I want Germans to open their eyes”. This line became the unspoken motto of the Klarsfelds. But their mission was even more serious – they wanted the world to open its eyes.

Lyon, 1942-1944

Klaus Barbie received a position with the Gestapo in Lyon at the age of 29. His father - a teacher and veteran of the First World War - had French roots, hence the francophone-sounding surname.

At the age of 22, Barbie joined the SS and was assigned to the SD, the Reich Security Service. In the spring of 1940, he began working for the Gestapo in the Netherlands. In 1941, Barbie went to the East, where he was searching for partisans in the occupied territory of the USSR. In 1942, the Nazi leadership was facing a growing resistance movement in France, and who else but Barbie with his excellent French would come in handy there?

In November of the same year, he arrived in Lyon, and in February 1943 became the head of the city's Gestapo.

By that time, Lyon was a think tank and headquarters of the Resistance. A powerful revolutionary tradition of disobedience to the authorities was alive there: one can recall the two uprisings of the Lyon weavers. Lyon had extremely developed transport infrastructure for the time: a rail link connected the city centre with remote villages, where people could hide from Nazi persecution.

By November 1942, three big resistance groups were already operating in the southern French city. Barbie's chief, SS Brigadefuehrer Carl Oberg, was sure that his subordinate would cope with the task. Oberg appreciated Barbie for his "ability to get things done".

Upon his arrival in the city, Klaus Barbie created torture chambers in rooms at the Terminus Hotel. Hooks were installed in the ceilings, on which people were hung with their hands twisted behind their backs and handcuffed. Trestle beds replaced normal beds, carpets were taken out, and the floors were covered with linoleum to make it easier to wash off the blood.

During interrogations led by Barbie, doctors were always present: they brought people to their senses when they fainted from the pain. Barbie tortured people himself. He beat people, peeled off their skin, and drove needles under their nails.

Survivors said he was tireless. The interrogations lasted for days. He once interrogated a victim for almost 50 hours. Then he left the cell, took a shower, cleaned himself up and went to have supper at the nearest restaurant.

While torturing members of the Resistance, Barbie always asked them the same question: "Do you know Max?" Max was the nickname for Jean Moulin, head of the National Council of the Resistance. In hiding, Max Moulin brought together three disparate groups into a united front.

He was betrayed by one of his associates. In June 1943, at a secret meeting, Moulin was arrested and taken to 14 Berthelot Avenue - to the former paramedic school, where Barbie had moved the headquarters of the Lyon Gestapo "due to the increased workload". Barbie tortured Moulin for 10 days to no avail - he did not utter a word. The “Butcher of Lyon” disfigured Max beyond recognition - his relatives were not able to identify the body of the antifascist.

Europe, USA, Bolivia

Klaus Barbie appeared in several lists of war criminals. Once he was even detained by the British, but he pretended to be a Wehrmacht soldier and escaped responsibility. He was sentenced to death twice - in 1947 and in 1954. But both times in absentia: in 1946, the butcher of Lyon disappeared without a trace.

There is evidence that at the beginning of 1946, Barbie was identified and interrogated by the French police, who even sent a message to Paris about the arrest of the “Butcher of Lyon”.

But in March of that year, Churchill delivered his Fulton speech. The Cold War, or the war against Soviet influence, had begun. The agents of the USSR included not only communists, but all leftist activists. In this war, the Americans needed Barbie. They wanted to use him to fight communists, and there was no better candidate for this role in Western Europe, especially in France, where the communists had a strong political voice.

With the help of agents, American intelligence officers found where Barbie was hiding, brought him to the headquarters of the OSS (Office of Strategic Services, the predecessor of the CIA), and made a business proposal: Barbie would give the names of all his agents who had infiltrated the French communists and he would receive money and security from the United States.

The beginning of the cooperation between the US OSS and the “Butcher of Lyon” dates back to early spring 1947. Entering the OSS building under guard, Barbie left it as a free man, with a number assigned to him as an agent and with almost 2,000 dollars in his pocket. This is how Barbie's romance with the CIA, which lasted for several decades, began.

Klaus Barbie worked for the CIA in the American Zone of Occupation, and when he in 1951 travelled to Latin America with his family via Austria and Italy, he did so through Vatican channels and carrying new documents.

There, Barbie became a rich and influential businessman. He traded in arms and dealt in the drug trade. His services were appreciated by the Bolivian military elite - a dictatorship under which he helped to deal with the opposition.

Today, it has been documented that a plan to assassinate Che Guevara was developed with the participation of Barbie and that it was he who taught the Bolivian police the torture technique of insisting that a doctor always be present during interrogations, who would not allow the victim to die prematurely.

Lyon, 1960s

The Klarsfelds set themselves a goal: to bring Barbie to justice for his crimes against humanity. The court could apply this legal norm thanks to the decisions of the Nuremberg Tribunal, which introduced it into legal use.

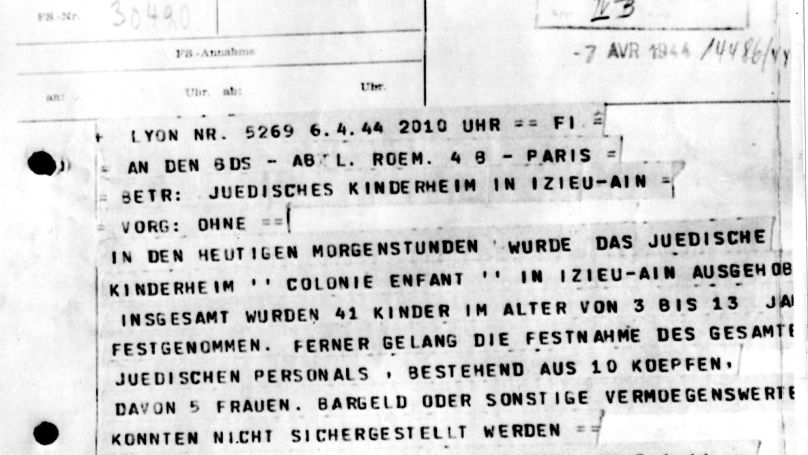

New material evidence was needed. The Klarsfelds went to the archives. By chance, they came across a telegram addressed to Barbie from the department of An, near Lyon. The local Gestapo reported that 41 Jewish children aged 3 to 13 were hiding in a Catholic orphanage in the village of Izieu. The telegram was signed by the "Butcher of Lyon" himself: he ordered to deport the children along with the staff to the Drancy internment camp in Paris. According to documents and evidence obtained later, Barbie personally participated in the raid on the orphanage.However, it had to be proved that Barbie knew that he was sending the children to their deaths while signing the deportation order. After months of searching, evidence was found.

One of the surviving prisoners agreed to confirm under oath that he had personally heard the phrase uttered by the Gestapo: "It's too bad to spend ammunition on these Jews, we will send them to the camp - the result will be the same". 20 years later, at the trial, this telegram became the most important evidence of crimes against humanity.

La Paz, 1971-1972

The Gestapo and US intelligence agent was so convinced of the reliability of the CIA's protection that he lived quite openly in La Paz, attending restaurants, social events, and state dinners.

At one of these dinners, German photojournalist Herbert John, a friend of the Klarsfelds, recognised him and called the Klarsfelds. The journalist said that the person they were looking for and the person he had seen in La Paz spoke Spanish with a German accent and that his name was Klaus Altmann. Having compared a wartime photo of the SS man with a photograph of “Altmann”, the Klarsfelds realised that they had found the “Butcher of Lyon”.

1971 was coming to an end. Testimonies of victims' relatives as well as circumstantial evidence of the identity of the Gestapo man and Bolivian businessman were obtained. The Klarsfelds lacked one piece of evidence, confirmed by expert examination, that would convince the court that Altmann and Barbie were one and the same person.

Ladislas de Hoyos had just been invited to work as a reporter for the French TV channel TF1. Knowing that the Klarsfelds had been hunting the Nazi for several years, he volunteered to help them. Ladislas spoke four languages, each of which he knew on a native level: German, Spanish, French, and Flemish. At the end of January 1972, he flew to La Paz with Beate Klarsfeld as part of his business trip.

Using his connections and paying bribes, he managed to interview the SS man “in order to dispel rumours that he was that terrible 'Butcher of Lyon’”.

The conversation was in German. At one point Ladislas handed his interlocutor a photograph of Jean Moulin and asked if he knew this person. “Yes”, Altmann-Barbie replied, picking up a glossy photograph, “I read something about him, I think in the Paris Match”.

And so he left his fingerprints.

The journalist immediately asked the following question: "Have you ever been to Lyon?" Without hesitation, the SS man answered in the negative. But the question was asked in French, and the answer was given in German. This meant that the Gestapo man knew the language of Moliere.

Barbie quickly realised his mistake, and when the interview ended, the TV crew was detained, ostensibly for a search, in fact - to seize the tapes. The operator managed to replace them, and the real records were delivered to the French Embassy.

The interview with the “Butcher of Lyon” was shown on the TF1 evening news bulletin. Barbie was recognised by the people he had tortured. Among them was Simone Lagrange - Barbie tortured her in front of her parents when the girl was 13 years old. Immediately after the interview was shown, a talk show began. “He pulled the scrunchie off my hair and grabbed it tightly”, Simone Lagrange said. ”This happened in front of my father's eyes. He tried to protect me, but Barbie put his pistol to his head".

After 10 days of continuous torture, the prisoners were thrown into a cattle carriage and sent to a concentration camp. Simone survived and returned to France.

1960s, The Context

General Charles de Gaulle, hero of the Resistance and founder of modern France, which he called the Fifth Republic, considered reconciliation with Germany to be his life's work. Only a lasting peace, good relations with a neighbour with whom France had endlessly argued over Alsace and Lorraine over the centuries, apart from other issues, could form the basis of a united Europe.

On 8 July 1962, at Reims Cathedral, where the monarchs of France used to be crowned, General de Gaulle and Chancellor of West Germany Konrad Adenauer attended a so-called “reconciliation mass”. The relationship between the two countries was very promising. But the geopolitical idyll had a price.

In November of the same year, the former chief of Klaus Barbie, Carl Oberg, who was in charge of the entire Reich Security Service in France, including the police and the Gestapo, was released from prison. Oberg was tried, sentenced to death, but then the execution was commuted to life imprisonment. But on 28 November 1962, de Gaulle's directive for the immediate release of the former SS Obergruppenfuehrer was sent to the Mulhouse prison, where Oberg was being held.

The business acumen of Barbie, who had settled in Latin America, attracted the attention of his compatriots. Klaus Barbie-Altmann was selected by the West German Foreign Intelligence Service (Bundesnachrichtendienst or BND) as an intermediary to help the authorities in Bonn to sell weapons to the military dictatorships of Latin America. He was even assigned a number: 43118.

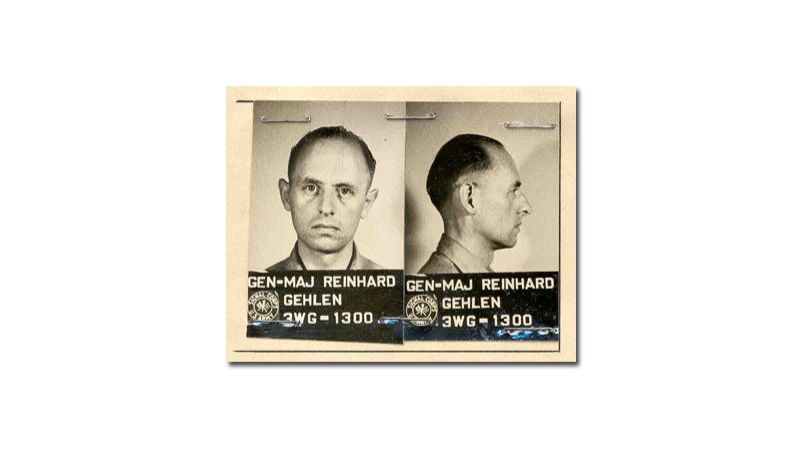

By the time of his recruitment, neither the identity of the “Butcher of Lyon” nor his past was uncertain. The reasons for such a lenient attitude were obvious: the BND was headed by Reinhard Gehlen, lieutenant general of the Wehrmacht and one of the intelligence chiefs on the Eastern Front during World War II. Gehlen himself surrendered to American troops, contacted US intelligence services, and convinced them to give him money to create an intelligence organisation where valuable former Nazis like him would work. The Americans were satisfied with the proposal, and that is how the BND was established.

Documents showing that the war criminal enjoyed the patronage of the intelligence services of West Germany were discovered only in 2011 by German historians.

Paris, La Paz, Cayenne, 1981-1983

The Klarsfelds had two children and a well-established family life. Serge was a famous Parisian lawyer and Beate was a journalist. But not a day went by when they were not working on the extradition of Klaus Barbie to France.

On 21 May 1981, on the day of his inauguration, newly elected President of France François Mitterrand went to the Pantheon, where he laid a rose (a symbol of the Socialist Party) on the grave of Jean Moulin, a hero of the Resistance, whom Barbie personally tortured to death in Lyon. After watching TV coverage of the event, the Klarsfelds contacted Mitterrand's foreign affairs adviser, who was their old friend. With his help, the Klarsfelds received an audience with the French head of state. The bureaucratic machine started to work: France asked the Bolivian authorities to extradite Barbie. This wasn’t the first time that they did so, but this time they did it more persistently.The new Bolivian government (by that time socialists had replaced the junta) considered the petition. But there was no extradition treaty between Bolivia and France. This meant that the Bolivians could not extradite Barbie to France - they could only expel him from the country. They needed a good reason for the expulsion. In addition, they had to send the criminal to a place where Paris would have the opportunity to arrest Barbie immediately. Bolivia's intelligence services began to dig into the past of the citizen Klaus Altmann.

It turned out that he had not paid duties and taxes after one of his firms was liquidated. Barbie was arrested on 24 January 1983 on charges of violating fiscal laws and put in prison. The ex-Gestapo man quickly collected the required sum of money - in theory he should have been released. But the harsh tax authorities found out that the penalty fee was huge by that time. Barbie didn’t have such money at hand.

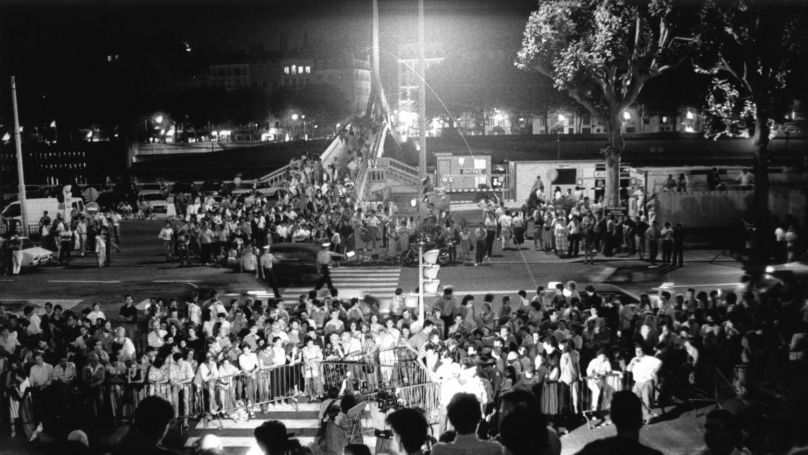

Bolivia's Interior Ministry issued a decree on the expulsion of Klaus Altmann to French Guiana. On the evening of 5 February 1983, a Bolivian Air Force aircraft headed for Cayenne.

On the night of 5 February, the head of the French Ministry of Justice, Robert Badinter, was awakened by a phone call. An employee of the presidential secretariat was on the line "Mr Minister, the Bolivian authorities have expelled Klaus Barbie from the country, the plane is flying to Cayenne; the local prefecture needs a document to bring charges against him".

Badinter froze up with the telephone receiver in his hand. The “Butcher of Lyon” had signed a list of arrested and deported Jews, one of whom was his father. Robert Badinter became an orphan at the age of 14.

The Nazi was certain he was flying to Germany. On the plane, a Bolivian TV journalist asked Barbie if he repented of his crimes. “Too much time has passed since that moment, almost 40 years. Who needs to dig into the past now? ", the "Butcher of Lyon" answered.

On the territory of French Guiana, Klaus Barbie was charged with crimes against humanity. He was taken to Montluc prison and placed in the same cell where Jean Moulin had been held. This was decided by Robert Badinter.

Lyon, 1987

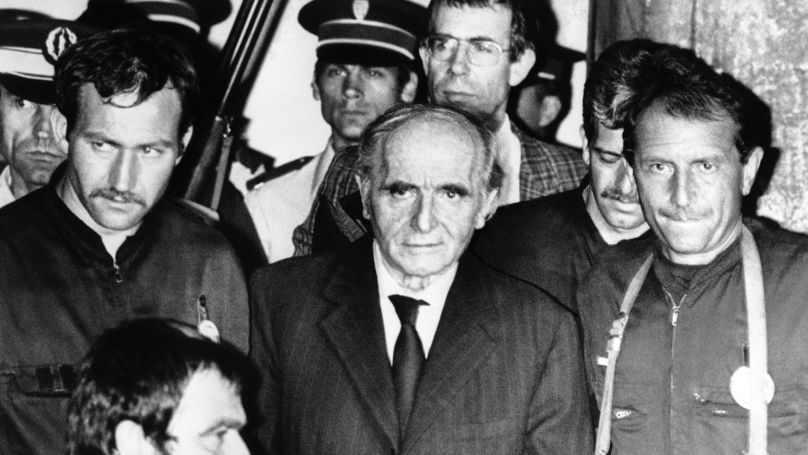

The trial began in May 1987. The process was open and television cameras were constantly running during the trial sessions, which had also been ordered by Robert Badinter.

Simone Lagrange was one of the key witnesses of the prosecution. “I was 13 years old, they carried me into the cell on a stretcher, I couldn't move from pain”, the woman told the trial.During the investigation and trial, it was found out that Klaus Barbie was personally responsible for the torture, death, and sending to concentration camps of 14,500 members of the Resistance movement; for the deportation and killing of over 6,000 Jews; and for the death of 44 children at the orphanage in Izieu. In total, 17 charges were brought against him. The victims' lawyers wanted to bring charges relating to the torture and murder of Jean Moulin as well, but the court did not accept them.

On the third day of the trial, Barbie stated through a lawyer that he refused to be present in the courtroom. French law provides such a right, and the court granted the request.

The case was considered by a jury. At the end of the hearing, the jury received more than 300 questions from the court. They answered all the questions in the affirmative. “No” was heard only once - in response to a question about extenuating circumstances.

On 7 July 1987, after four years of investigation and three months of trial, the 74-year-old “Butcher of Lyon” was sentenced to life imprisonment. He died in prison shortly after from cancer.

By Angelina Pavlova