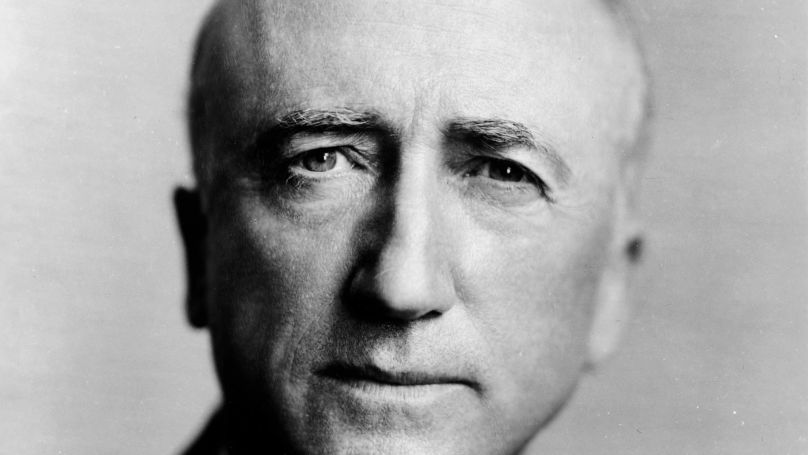

On 28 May 1946, French representative Léon Blum and US Secretary of State James Byrnes signed a protocol on the implementation of the Marshall Plan between the two countries. The agreement mainly concerned the film industry.

Before World War I, France was the undisputed leader in film production with a market share of 90 percent. However, by the 1930s, foreign competition had effectively strangled French cinema and before World War II, the United States had won a clear victory in the local market – a wave of Hollywood products had reduced the share of French films at the box office to 30 percent.

After World War II, the French film industry was in decline and required investment and state support. Rescue was sought with the introduction of restrictions on the distribution of foreign films. But this in no way suited the interests of Hollywood, still promoting their products in France at cut-rate prices and calling it “free competition”.

France’s economic situation left much to be desired. American aid, debt restructuring, and new loans were needed. James Byrnes took advantage of this by lobbying top Hollywood figures (he would become a consultant to several major studios once he retired). The weakness of post-war France allowed the US to impose a solution that fully satisfied Hollywood.

Under the agreement, the US forgave a French debt of $1.8 billion and provided another loan of $500 million. In return, the French film industry was to cede even more ground. French films were now only shown at home for the first four weeks of each quarter. At the same time, their importation and release were not guaranteed in the US. Nevertheless, the pot was sweetened: American companies agreed to invest the box office profits in the French economy.

Léon Blum commented: “I must admit that, if in the higher interests of France, I had had to sacrifice the film industry, I would have done so without a qualm”.

The agreement would bring about a further 50% decline in French film production within a year, which had already been decimated. Most film historians would later point out that the agreement was a major setback for the development of French cinema. After strong protests from intellectuals and the film industry, the agreement was cancelled in 1948 and a special tax was imposed on the release of American films, with the money going to the National Film Centre to support French film projects and cinemas. Today, the annual tax is 700 million euros, which is used to finance, among other things, the Cannes Film Festival.

Source:

Yuri Sher, “French Cinematography Fighting for its National Independence” // French Cinematography, Мoscow, 1960