The Nuremberg Trials were the first of their kind in history, turning into a judgment against a regime and an entire era - the Nazi period that gripped Germany for one and a half decades. It gave a powerful impetus to the development of international law. In particular, it introduced the concept of "crimes against humanity" that we use today. The forging of a new term, a key one for the advancement of human rights, took place amid heated legal debates and even intrigues around the two concepts – "genocide" and "human rights". Georgy Bovt discusses the key legal collision for the modern world.

Verdict against Era and Regime

The first session of the Nuremberg Trials on 20 November 1945 was chaired by British Judge Geoffrey Lawrence. Each delegation from the victorious powers was entrusted with the task of reading out a different paragraph of the indictment. The American prosecutor read out the count of conspiracy to commit war crimes. The British one on crimes against peace and security of humanity. The French prosecutor read out the war crimes count, including genocide. Roman Rudenko, 38, (then Procurator-General of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and later Procurator-General of the USSR) represented the Soviet Union and indicted them for "crimes against humanity". Over the course of almost a year, 403 trials were held, 240 witnesses were interviewed and more than 300,000 affidavits were studied. Of the 24 accused, 13 were sentenced to death (one – Martin Bormann – in absentia), three to life imprisonment, four to different terms, three were acquitted. Curiously enough, surveys in 1946 showed that 80% of Germans thought the sentence was fair and the guilt of the defendants undisputed. And yet a few years earlier they had saluted the murderers with enthusiasm...

The Tribunal condemned the crimes of not just the individual leaders of the Third Reich and the leadership of the Nazi Party, but also the organisations that comprised the political infrastructure of Hitler's regime: the Sturmabteilung (literally Storm Detachments, SA), the Schutzstaffel (SS, a punitive organisation), the SS Security Service (SD), the Secret Police (Gestapo), the national government and its General Staff. All crimes were divided into three blocks: against peace (planning, preparation, unleashing or waging a war of aggression in violation of international treaties); war crimes (violation of laws or customs of war); crimes against humanity (extermination of whole nations, the establishment of special camps for exterminating peaceful population, etc.).

We have become used to the very term "crime against humanity" being firmly associated with Nuremberg. However, strangely enough, this particular qualification of the Nazi atrocities did not emerge immediately, but gradually, through heated legal debates.

First of all, it should be borne in mind that international law itself was at an early stage of development, even if the results of World War I and the disintegration of several empires directly contributed to the growth of the rule of law, which was used to find solutions to such pressing problems as the rise of nationalism and the protection of minority rights, for example. When the League of Nations (a modest precursor of the UN) was created, the question of some countries' membership being linked to the obligation of granting equal rights to national minorities was discussed. But for some reason, in practice, the founders of the League of Nations only applied this requirement to Poland, which received some "pieces" of the disintegrated (or as they called it – "patchwork") Austro-Hungarian Empire. Poland itself had gained independence by seceding from the Russian Empire.

It is not difficult to guess that the colonial powers, Great Britain in particular, were against extending this principle to the rest of the world. Don't use your "international law" to interfere in the affairs of our "sovereign empire", they said. However, the rules were forced on Poland: the rights of its national minorities - such as granting citizenship to the inhabitants of its new territories, as in, for example, Lviv, which had been integrated into the country - became obligations at the international level. This was enshrined in the so-called Little Treaty of Versailles.

However, as further history has shown, the "selective principle" in law enforcement leads to its inevitable undermining and discrediting.

And Poland, by the way, having just signed its non-aggression pact with Germany (four years before the USSR), later denounced the treaty’s provisions on national minorities. Don't meddle in our internal affairs, the proud Poles told the world. And while the same anti-Semitism in pre-war Poland did not reach the scale (and repression) of Nazi Germany, it was still a very ugly phenomenon, and very much a state-run one at that. And Warsaw was not beholden to the "world community" in this matter. Neither was Germany for the time being.

At that time, Europe (and even more so outside Europe) was dominated by the idea that the state, based on its sovereignty, could do whatever it wanted with its subjects, so that any discrimination on the grounds of nationality and religion was not considered "illegal" (even if it was morally condemned) from the point of view of the then-fledgling international law. But does this mean that even the Nazi (those same "Nuremberg") laws of 1935 on the purity of the Aryan race were fully compatible with this standard? And, mind you, nobody, in fact, challenged them at the international level before the outbreak of World War II: there was simply no formal legal basis for this.

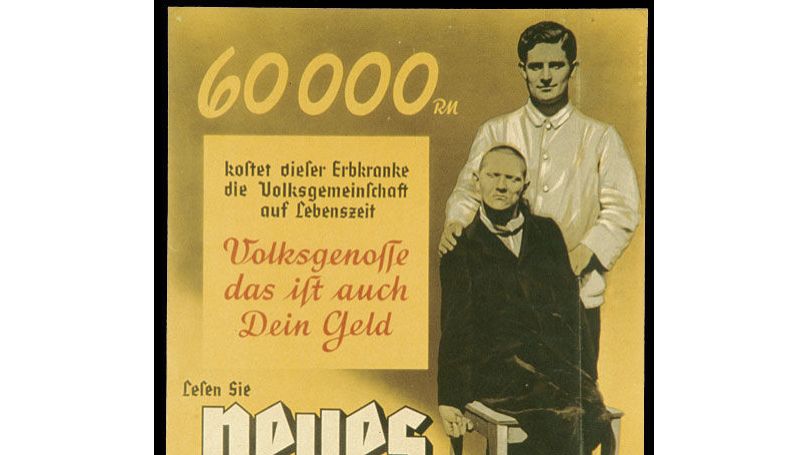

For example, in Nazi Germany the Marriage and Engagement Act of 1935 allowed outwardly healthy siblings and children of hereditarily disabled people to enter into only such marriages, which would be childless. The exchange of certificates of hereditary family characteristics became compulsory at the time of marriage. The forced sterilisation of "substandard human material" became widespread. The decision to sterilise was made by special "hereditary health" courts.

The humiliation was extended to those found to be suffering from dementia, schizophrenia, manic-depressive illness, epilepsy, congenital blindness or deafness as well as a range of genetic diseases. Chronic alcoholics and those with tuberculosis, syphilis and gonorrhoea were not eligible to procreate. Not only that, but the Nazis also invented a special term "moral deficiency" that could be applied to anyone. For example, to those who 'failed to conform to socially accepted norms of behaviour', 'failed to run a profitable business' or 'failed to recognise their responsibility for bringing up children'. Children who, for example, failed at school or had childhood illnesses, could also be considered “morally deficient” with all the ensuing consequences. Around 360,000 to 450,000 Germans were forced to undergo sterilisation from the mid-1930s to 1945. However, these people were never recognised as victims of the Nazis and none of the doctors working in the hereditary health courts were punished.

It was only after the war began that the warring powers began to think about what to do with the Nazis after victory. From the outset, it was a question of punishing war crimes, the concept of which (like the international rules of warfare) had developed by the outbreak of World War I or even earlier.

In 1942, nine European governments in exile, including those representing Poland and France, signed the so-called St James Agreement, which recorded their intention to punish the Nazis for the atrocities committed against civilians in the occupied territories. However, in war conditions, information about this was fairly scarce, and no one knew, even in England and the US at the time, all the horrors in occupied Europe. There was little knowledge of the atrocities committed by the Germans in the distant and “incomprehensible” USSR.

Genocide or Holocaust?

In any case, these were originally war crimes. There was no very concept of "crimes against humanity", and even more so there was no term such as "genocide", which international lawyers are familiar with now, which is understood as the purposeful destruction of certain groups of people, or committing other humanitarian crimes against them, including the destruction of language, cultural heritage and so on. This is precisely what the Nazis did in the occupied Slavic countries and particularly ruthlessly in the USSR.

Here, for example, is just one tragic story that has not become widely known until now. Everyone knows about the tragedy of the Belarusian village of Khatyn, where the Nazis burned 149 people. But in March and October 1942, some 385 and 360 people were killed in the villages of Sanniki and Andriukovo of Velikolukskiy District. In March 1944, Guards Captain Talashkin arrived in the newly liberated Velikiye Luki and began interrogating surviving witnesses, exhuming victims and conducting medical examinations. And here is just one account. Poletaeva Anastasia Yermolaevna, 45, place of birth: v. Zamoshie, Velikoluksky District, Kalinin region; housewife, Russian, non-party; no criminal record; collective farmer. “They began to gather citizens - men in one group and women and children in another group. I and Fenya came out of the stable, and we crawled to leave and hide, but two Germans caught us. One of them ordered us to go to the group of citizens, and the other ordered us to harness their horse. We started harnessing horses, we harnessed seven horses, one horse per sledge. These Germans took the horses, loaded all of the citizens' miscellaneous possessions onto the sledge and drove off in the direction of the village of Bachevo.

We did not join a group of citizens, but hid again. One old man and a girl came running to us, who had jumped out of the burning house; I do not know their names. The people gathered in groups - men, women and children - were shot by the Germans, and the village of Sanniki was burnt down.

By the evening of 17 March 1942, when the Germans had massacred the civilians, they left for Bachevo village. I, Fenya, an old man and a girl went to see what the Germans had done. When we approached the place where groups of citizens were standing, we saw a nightmarish scene - there were piles of corpses, some of the citizens were alive, they heard our conversation and began to raise their heads. A girl of about twelve years of age, unharmed, pulled a five-year-old boy with a broken leg out from under the bodies. This girl rushed tearfully to the old man and said, ‘Uncle, uncle, the Germans have killed mother and the other children’. Three women and three wounded men rose from the pile, and the other four hundred were shot and burned.”

What is this if not genocide?

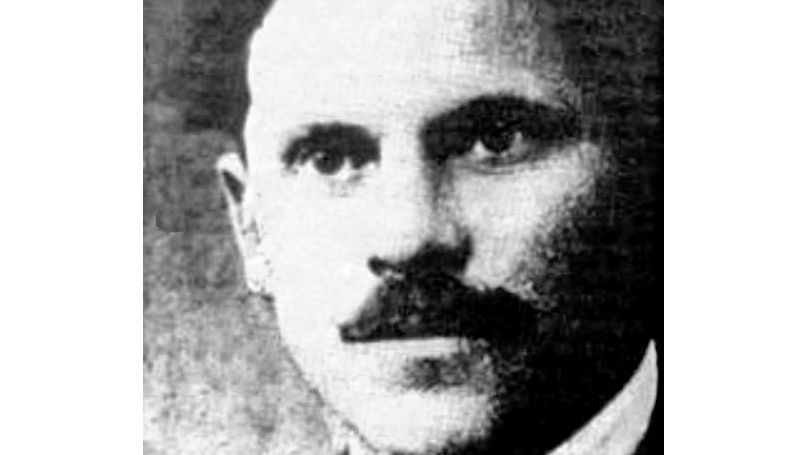

The term "genocide" was first proposed by Raphael Lemkin, a former Polish prosecutor of Jewish origin (he had just been expelled from his position as a prosecutor on grounds of nationality) who emigrated to the United States. In his book The Axis Rule in Occupied Europe, published in the United States in 1944, he drew on the concept of "Holocaust", found in a Latin translation of the Bible (and first used in chronicles of the second half of the 12th century, describing a Jewish pogrom of 1189 in London). Incidentally, the English-language press used the term "holocaust" to describe the extermination of Armenians by the Turks in 1915. We are now accustomed to those tragic events being referred to as such.

However, neither the Western world, nor the specialists of the emerging international law at the end of World War II were generally prepared to recognise genocide as a punishable crime.

We now know as a matter of course that Nazi Germany wanted to wipe entire nations off the face of the earth, to change the national composition of Europe dramatically. This policy was based on an elaborate "legal basis" of national, sovereign law for the Third Reich. The pedantic Germans (ideologists and jurists of Nazism) tried to put everything in its place.

The fact that no decisive action was taken at Nuremberg against this ideology - and against the acts of the Nazis before the war - may be because the enormous scale of these atrocities took hold slowly and was not fully understood by the legal community.

Besides, the inertia of a certain perception of Germany as a military adversary from World War I may also have had an impact: the Germans did not commit such terrible crimes against civilians in those years. Finally, it was only as the Red Army advanced westwards and liberated the occupied territories that the full extent of the Nazi atrocities in the USSR and Eastern Europe became apparent, information about which until then was scattered and unverified.

Curiously, a theoretical opportunity to introduce this new concept into the emerging international law was present even after the end of World War I. Some British and US jurists had familiarity with the Armenian genocide, for example, and characterised it as a "holocaust", a crime against a very specific national group. True, they also called the Jewish pogroms in Tsarist Russia at the time of Alexander III by the same word. Of course, the British were not prepared to look at their own colonial policies from this perspective (although the British were not particularly atrocious, but by today's standards, and especially against the backdrop of the Black Lives Matter movement, there must have been something to pick on).

In 1921, there was a trial in Berlin, which could be considered as important for the "Armenian question" as the Dreyfus affair was for the Jewish question. Soghomon Tehlirian, an Armenian student, was on trial. Short, dark and pale, he made no secret of the fact that he assassinated former Ottoman Minister Talaat Pasha, who had visited the German capital. But he did it to avenge his fellow countrymen, who had been massacred in Erzurum, Turkey, in 1915. Talaat Pasha had been directly involved.

The defence relied on the fact that the defendant had acted in the heat of passion. The jury comfortably agreed, acquitting Tehlirian. Later, Lemkin would debate this "case" with university professors: did Tehlirian have the right to act as a "policeman" who arbitrarily tries to restore justice? Did the Armenians (who were slaughtered and killed) try to go to the police in search of justice? Yes, they could have. Because, after all, Talaat Pasha had acted entirely "legally".

Again, at that time jurisprudence was based on the assumption that any state was free to do whatever it wanted with its subjects according to its national jurisdiction. So long as there was a law to that effect, it was not legally a "genocide" or "holocaust".

Later, a similar trial was held for the murderer of a more familiar character, the Ukrainian nationalist Symon Petliura, murdered in Paris in 1926 by a Jewish watchmaker, Samuel Schwarzbard. This was his revenge for the Jewish pogroms carried out by Petliura's formations during the Ukrainian Civil War.

Schwarzbard was also found not guilty of “involuntary manslaughter”. In both cases, the jury was thus "correcting" the shortcomings of international law at the time.

At the same time, these two dramatic processes show how acute the issues surrounding what is now called "national identity" were among the ruins of several empires that passed away and which broke apart not through peaceful "divorce" but through war and revolutions. And it took place in the absence of the very international law that could make this process at least somewhat manageable. By the way, this "international legal negligence" would come back at the end of the 20th century, when Yugoslavia, a state that was created, in fact, artificially, after World War I also collapsed in a bloody way. Since at the time the great powers loved to draw the borders of states rather arbitrarily, there were many cases similar to Yugoslavia in the first half and the middle of the 20th century (Syria or Iraq, for example).

How Lawyers ‘Invented’ Human Rights and What This Led To

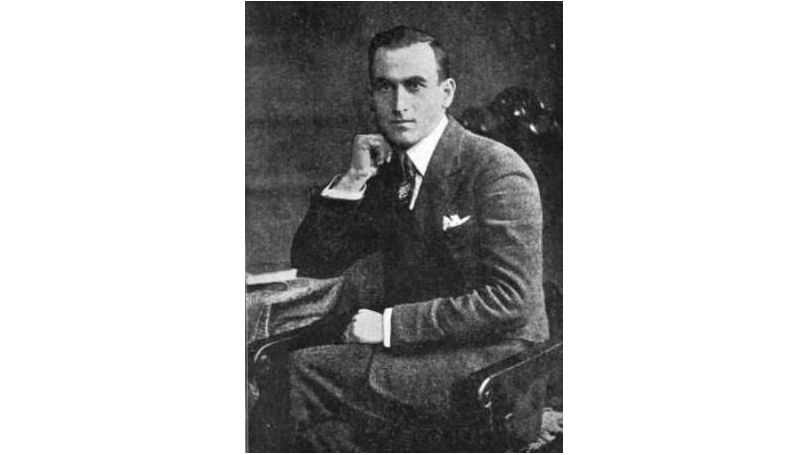

The opponent of Lemkin during the preparation for and throughout the Nuremberg Trials was the legal adviser to the American and British representatives at the tribunal, Professor Hersch Lauterpacht of Cambridge, one of the authors of the modern concept of human rights and the Declaration of Human Rights. The predominantly extramural legal "duel" between these two eminent legal scholars is described in Philippe Sands' book “East West Street”. Lauterpacht not only disapproved of the concept of genocide at Nuremberg, but lobbied hard to keep this particular point out of the case. He argued that, firstly, making such an accusation is impractical from a legal point of view, as the criteria are too vague and the legal practice of making such accusations is not well established. Secondly, a focus on the rights of particular groups of people (including national groups) detracts from the protection of the rights of the individual. Moreover, defending "group interests" can create the threat of a division into "us" and "them" and will only exacerbate inter-ethnic tensions. For his part, Lauterpacht insisted that in the post-war world it is the rights of the individual that must be placed at the centre of international law and rise above national jurisdiction. Partly with his counter-argument, the professor was looking decades ahead. Indeed, nowadays, sometimes we do face some speculations in this respect: the very term "genocide" on the lips of some politicians has become a means of rhetorical manipulation (modern politics generally likes such drama-driven “hype”). However, this is too delicate a topic to delve into further.

Little Legal Tricks and a ‘Duel’ of Two Legal Scholars

It is remarkable at times what subtle intrigues and stratagems people have used to promote ideas they believed in and considered right. There is no self-interest or even vanity.

Hersch Lauterpacht personally went to great lengths to ensure that international charges were brought against the Nazis at Nuremberg, but specifically in his version. For starters, for example, he decided to use his friendship with US Supreme Court Justice Robert Jackson, whom President Truman had appointed as chief prosecutor at the Nuremberg Tribunal. At the same time, he carefully concealed from Jackson the fact that several members of his own family had perished during the occupation of Poland and Ukraine. Otherwise, it would have appeared to be a case of personal revenge, which is unacceptable for a jurist. They met in London in July 1945, having already known each other for several years. They were working on a draft agreement for the setting up of the first international tribunal, something that had not existed as a legal precedent before. At first, for example, the USSR insisted on three charges: aggression, atrocities against civilians during the war and violating the laws of war. The Americans proposed adding two more: waging a war of aggression and membership in a criminal organisation (e.g., the SS).

In order to convince the Soviet and French delegations (for some reason, the Americans were sure that they would not support their proposal), a new term was invented for atrocities against civilians in the war – 'crimes against humanity'. It was coined by Hersch Lauterpacht.

It is curious that Lauterpacht's absentee opponent, Raphael Lemkin, also contacted the US prosecutor, Robert Jackson, in the summer of 1945. Lemkin, who did not know Jackson personally at the time, sent him his book “Axis Rule in Occupied Europe". Jackson read it carefully, making notes in the margins. In particular, opposite the quotation of Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, one of the authors of the plan of the German invasion of the Soviet Union – "Operation Barbarossa". The marshal allegedly said that Germany's greatest mistake during World War I was to "spare the lives of civilians in enemy countries", when it was necessary to destroy at least a third. Was this not a genocide, Lemkin argued, trying to sway Jackson's view. And it had a certain effect. Jackson himself put the word "genocide" on the list of charges in May 1945 when the American draft indictment was prepared. And in late May, Lemkin was added to Jackson's team of advisers and began serving on the War Crimes Commission. But in July, Article 6 of the Tribunal's Statute included crimes against humanity (in Lauterpacht's wording), but did not include genocide (in Lemkin's wording) as a separate item. Lemkin was almost forced out of Jackson's team working in London as a result of intrigues by British members of the drafting team. Genocide was included in the general list of crimes (under "war crimes") but not under "crimes against humanity". It was only a partial victory. It can generally be said that the Nuremberg legal documents were dominated by Lauterpacht's concepts and formulations.

The two "duelists", Lemkin and Lauterpacht, were not known to have met in person, except fleetingly or accidentally. Neither had any personal animosity towards one another. It was just a battle of ideas...

Nuremberg Lessons Learned Only Half a Century Later

One of the indictments proposed by the Soviet delegation - crimes against civilians - was eventually transformed, although not without hesitation (one has to keep in mind that the legal mind requires the utmost specificity), into "crimes against humanity", which is the term we firmly associate with the Nuremberg Trials from our school days (at least those who were diligent in their studies). And this is what Article 6 (c) of the Tribunal's Statute looked like as of 8 August 1945: “Murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation, and other inhumane acts committed against any civilian population, before or during the war; or persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds in execution of or in connection with any crime within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal, whether or not in violation of the domestic law of the country where perpetrated”. But then, in October, the semicolon was replaced by a comma and the new legal interpretation was that pre-war events in Germany (the "Nuremberg Laws" on the purity of the Aryan race, for example) were excluded from the tribunal's jurisdiction and that only crimes committed from September 1939, after the war had already started, were put on trial. This version has been put forward by some scholars (including the aforementioned Sands) and is indeed effective. However, it is not just a matter of a particular punctuation mark, of course, but of the general mood, above all that of the jurists of the victorious colonial powers, mainly Britain. They feared an expansive interpretation of the crimes committed within national jurisdiction and not directly linked to the war.

As we can see, the word "genocide" was omitted here. Later it did appear in the section "war crimes", but not in the section "crimes against humanity". The final verdict did not include the word "genocide" at all, and it was very rarely mentioned during the trial.

Only after the verdict of the Nuremberg Trials did the UN take a new step in the development of international law by recognising genocide as "a crime subject to international law". This is what the relevant Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide says.

During the Cold War, it was hard to imagine that the victorious powers of World War II would agree on the consistent implementation of the blood-won principles of international law, including those elaborated at the Nuremberg Trials.

A breakthrough in this respect was made in the 1990s, when articles about "the end of history" and the possibility of unifying the world on the basis of a "universal" liberal platform and its adopted interpretations of human rights were in vogue. The status of the International Criminal Court (its prototype was established in The Hague in 1922, but did not really make a name for itself - in fact, before the war it had no "subject" of examination due to the underdevelopment of international law) was finally confirmed. The "new" International Court of Justice was designed primarily to condemn the crimes committed in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda. Moreover, this was a time when there was an international consensus among the major powers (and after the collapse of the USSR, the principal opponent of the West) that such crimes should be punished. Time has now passed and it is clear that international justice was more impartial with regard to the crimes in Rwanda, but the "Yugoslav case" was more politicised. Therefore, the number of convictions in the latter case was heavily skewed in "favour" of the Serbs. What NATO did not "finish", was finished off by the International Court of Justice in The Hague. Incidentally, the first state to be convicted by the International Court of Justice for a violation of the Genocide Convention (even though it was non-binding) was Serbia - for failing to prevent acts of genocide in Srebrenica. However, the Albanian warlords convicted of organ trafficking and then promoted to "statesmen" have been largely untouched by international justice.

The first indictment for crimes against humanity by a national court was the 1998 British court decision in the case of Augusto Pinochet: the former Chilean dictator was denied immunity from British justice. But then again - could there have been such a trial during the Cold War, all the more so when Pinochet was still in power, having overthrown the socialist (hence Soviet ally) Salvador Allende?

The first incumbent head of state convicted of genocide was the Western-maligned President of Sudan, Al-Bashir, in 2010. Two years later, Liberian President Charles Taylor became the first head of state convicted of crimes against humanity. Both of these verdicts look fair enough, but they still affected countries far from the first order. As for the world's leading powers, international law remains timid towards them. No major power, however, has spawned a figure or regime similar to Hitler and the Third Reich. So the lessons of World War II have not been forgotten after all.