Charles De Gaulle's handpicked prosecutors rehabilitated France that had surrendered to the Nazis

France – the only victorious power to survive a complete occupation. Collaborationism became a national problem. Therefore, the Nuremberg trials marked the beginning of a new identity for the country. The French prosecutors chosen by de Gaulle for the trials had one thing in common: they were all members of the Resistance movement.

Defeat in Six Weeks

France declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939, after the Nazi aggression against Poland, but did not engage in active hostilities.

On 10 May 1940, German troops invaded the Netherlands and Belgium; three days later, the Wehrmacht crossed the Belgian-French border, and on 8 June, the Germans had already reached the River Seine, where Paris is situated. After another two days, the French government moved to the Orleans area, then to Bordeaux. On 14 June, Paris surrendered; on 17 June, the government requested an armistice with the Third Reich and signed it on 22 June in the forest of Compiègne – the same place where Germany capitulated in World War I. The war saw France lose 84,000 men killed and over 1 million prisoners – almost the entire French Army.

On 10 July 1940, the national assembly in the city of Vichy proclaimed World War I hero Marshal Philippe Pétain as “chief of the French state” and gave him dictatorial powers. De jure, the new pro-Nazi state controlled all of France, but in practice, only the centre and southeast were under its control - the north and west were occupied by the Nazis. Marshal Pétain and his government were based in the spa and resort town of Vichy (hence the name Vichy regime).

In November 1942, fearing an Allied landing, German-Italian forces occupied all of France almost without resistance. The power of the puppet government became purely nominal and collaborationism in the country became commonplace.

‘Bah! And the French Are Here!’

However, there was another force in abroad – the Free France movement (from July 1942, Fighting France), led by Brigadier General Charles de Gaulle. On 18 June 1940, he had called for resistance against the Nazis. De Gaulle's status was not entirely clear (he had not been elected by any legitimate body), but British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, and then the leaders of other powers, recognised the general as the leader of “all free Frenchmen”. Members of the French Resistance began to gather around him.

During the liberation of France – first the African colonies and then the mother country – power shifted to de Gaulle and his supporters. In the spring of 1945, the country was among the four powers that accepted the surrender of Nazi Germany. This fact so surprised Hitler's elite that, according to de Gaulle's recollections, at the signing of the instrument of surrender on the night of 8-9 May 1945, Wilhelm Keitel, Head of German Armed Forces High Command, exclaimed in amazement: “Bah! And the French are here!”

In de Gaulle's view, Keitel's words should be understood as “France and its army did not waste so much effort and sacrifice for nothing”, he wrote in his war memoirs. But this phrase has also been reported in a less favourable form. For example, the version by Die Zeit editor Karl-Heinz Janssen: “And the French, too? That's the last thing we need”.

Why was France placed alongside the USSR, the United Kingdom, and the United States when no one else in continental Europe was so honoured? There was general sympathy for de Gaulle and other French patriots, but there was also a delicate balance. The Americans and the British wanted an authoritative partner that did not favour the Soviet Union. For example, Yugoslavia, where the guerrilla movement had been active throughout the war, was not suitable for this role: the communists had come to power there.

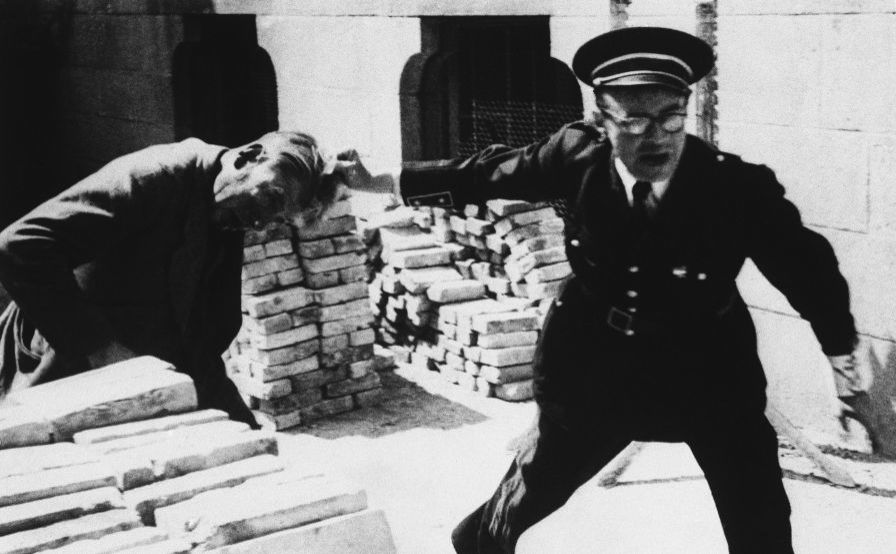

How France survived the occupation of 1940-1944. Photo chronicle:

Delegation to Nuremberg: Between Struggle and Compromise

Charles de Gaulle, who became President of the Provisional Government of the French Republic, sought to strengthen the role of France in the anti-Hitler coalition. His decree of 8 October 1945 on the formation of a delegation to the International Military Tribunal served this purpose.

It was comprised of judges, prosecutors, interpreters, secretaries, and stenographers. Taking into account military officers, communication officers, journalists, and diplomats, the number of French representatives at the trials had reached 262 by January 1946. This was the second-largest delegation after that of the United States.

The prosecution team included fifteen people, of whom twelve spoke at the trials. As researchers note, the French prosecutors were a fairly homogeneous group: almost all of them had been members of the Resistance and had fought against Nazism. This choice was certainly not random.

At the same time, the Ministry of Justice was well aware that during World War II all court officials and prosecutors who had not left the country were obliged to obey the Vichy regime. Most officials, including those who were anti-Nazi, had sworn allegiance to Marshal Pétain. Even among the members of the delegation at Nuremberg were those who had at one time openly demonstrated loyalty to the Vichyists: Serge Fuster, Jean Leiris, and Pierre Munier. But the public had no complaints about the men in the group of prosecutors.

Gaullist Legal Professionals

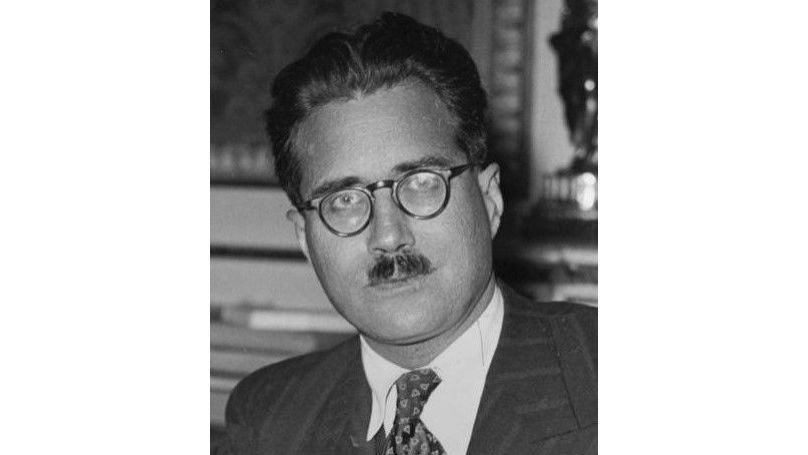

De Gaulle appointed Professor François de Menthon, who came from an old noble family, as Chief Prosecutor for France. Following the German aggression against Poland, de Menthon became a captain in the French Army. In June 1940, he was seriously wounded, taken prisoner, escaped, and joined the Resistance. He edited an underground newspaper and was one of the leaders of the anti-fascist organisation “Combat”. In 1943, de Menthon moved to London where he worked with Charles de Gaulle. He served together with de Gaulle in Algeria from 1943 to 1944. After the liberation of France, he became Minister of Justice in de Gaulle's Provisional Government of the French Republic, then the Attorney General of France. During his tenure, he fought against collaborators, even attending the trial of Pétain and members of the Vichy government.

In January 1946, de Gaulle resigned, followed by the faithful de Menthon leaving Nuremberg. Auguste Champetier de Ribes took over as Chief Prosecutor for France.

A 63-year-old lawyer and politician, de Ribes fought in World War I, was wounded, and later decorated with the Legion of Honour. He was a deputy, senator, and minister from 1924 to 1940. On 10 July 1940, de Ribes was one of 80 parliamentarians who voted against granting dictatorial powers to Marshal Pétain.

During the occupation, Champetier de Ribes headed an underground group, and became the first party leader to recognise the authority of General de Gaulle. He was interned for his opposition to the Vichy government and spent 18 months in prison. After Nuremberg, in the autumn of 1946, he won the election for the presidency of the Council of the Republic, but subsequently lost the national presidential campaign. Illness, however, prevented him from carrying out his work in parliament – Champetier de Ribes passed away in March 1947. His funeral took place in Notre Dame de Paris.

The deputy chief prosecutors could boast an anti-fascist past too. Charles Dubost joined the Resistance during the occupation and ran a local intelligence network. He was captured, then escaped, took part in transporting weapons to Algeria, and lodged Allied officers who had secretly landed in occupied France in his house. After Nuremberg, Dubost participated in the prosecution of French collaborationist businessmen.

Another deputy, Edgar Faure, joined the Radical-Socialist and Radical Republican Party when he was young, got married, and went on a honeymoon to the USSR. In the autumn of 1942, he moved to Africa with his family and joined de Gaulle in Algeria. There he became head of the legislative body of the Provisional Government. After the Nuremberg trials, Faure had an impressive political career, serving as a minister in many governments. He was also a university lecturer and wrote books on famous economists.

The group of assistant prosecutors for the French chief prosecutor included quite a few bright personalities: Pierre Mounier was a judge and a member of a Masonic lodge, Charles Gerthoffer, an expert on economics, Constant Quatre, a military expert, Serge Fuster – a judge and writer who achieved literary fame under the pseudonym of Casamayor.

Delphin Debenest was a true hero of the Resistance. He gathered information for the underground, and in June 1943 became a Free France intelligence agent. He was arrested by the Gestapo and sent to the Buchenwald concentration camp. In April 1945, Debenest took advantage of the confusion during a bombing and escaped from the camp.

Heinz Meyerhof, a German Jew, was hiding under the name Henri Monneray. He lived illegally in occupied France. He used smuggling routes to connect the Resistance with Allied pilots. Jacques-Bernard Herzog participated in the Resistance movement in Toulouse. When the Gestapo got on his trail in the winter of 1943, he fled to Spain and suffered frostbite in the Pyrenees, causing him to have his left leg amputated.

But there was a weak link in the brave Gaullists' team – Henry Delpech. In January 1946, he submitted a report at the Nuremberg trials about the Nazi pillaging of Belgium and Luxembourg. The next day French soldiers, with whom Delpêche had once been arrested by the Germans, claimed that during the occupation he had belonged to a Pétainist circle. Fearing publicity, the Ministry of Justice immediately summoned the lawyer to Paris, where he was informed of his expulsion from the delegation to Nuremberg.

Expert Commentary

On Behalf of Western Europe

Sergei Miroshnichenko, a lawyer and international law scholar, explains the role of the French prosecution at the Nuremberg trials.

At the Nuremberg Trials, the French found themselves in a difficult political situation. By signing the Armistice of Compiègne, France had recognised the legitimacy of German forces on its territory. Hence, the French held the idea that the Resistance actions against the German Army were the actions of the regular army.

The French prosecution presented evidence under Counts Three and Four of the Indictment – war crimes and crimes against humanity against prisoners of war and civilians in Western Europe.

The presentation by the French prosecution of a number of witnesses who had survived the Nazi concentration camps was significant and impressive: Paul Vaillant-Couturier, Francois Boix, Maurice Lampe, Jean-Frederic Veith, Paul Roser, Victor Dupont, Alfred Balochowski, and Hans Cappelen. The witnesses described horrifying details of the mechanism used to exterminate people in the camps in a variety of ways and with cannibalistic ferocity. The only thing the defence could counter the testimony with was that the defendants were allegedly unaware of these practices.

Testimonies on Nazi massacres of patriots contained serious accusations against the Wehrmacht, the SS, and the Gestapo. There were examples of hostage-taking, torture of those captured, and the massacre of civilians who supported the Resistance movement.

The French prosecution meticulously gathered facts about the economic exploitation of Western European countries and the export of labour to Germany. Some forms of exploitation would now be called “unfair competition” by the German authorities: the appointment of Germans to the boards of directors of French firms, currency manipulation, the charging of exorbitant occupation fees, the luring of workers to Germany, and the corrupt enrichment of collaborators. All this was done with the assistance of the Vichy government. The introduction of German legislation and Nazi propaganda were also regarded as crimes by the French prosecution.

In solidarity with the representatives of the Soviet Union, the French prosecutors vehemently protested against the defence counsels' attempts to portray German conduct in the West as self-defence against communists.

However, when the Soviet prosecution started the presentation of its evidence on the same sections, the striking difference between Nazi policy towards Western countries on the one hand, and towards the Soviet Union on the other, became evident.

The dominant form of economic exploitation carried out against the Soviet Union was the looting of civilians, and the punishment for resistance was execution. Whereas Western POWs enjoyed treatment under the Geneva Convention, Soviet POWs died of starvation and hard labour. While collective punishment of the population in the West, such as the burning down of villages, was an exception, in the East – it was the rule. The Nazi leaders discriminated between “superior” and “inferior” races and the war in the East became a war of annihilation in the full sense.

Sources:

Sergei Miroshnichenko, “Transcript of the Nuremberg Trials”, Volume I-VI

Matthias Gemählich, “Notre combat pour la paix”: la France et le procès de Nuremberg (1945-1946)

Jean-Paul Jean, “Les magistrats de la Cour de cassation au procès de Nuremberg”

Charles De Gaulle, “The War Memoirs of Charles De Gaulle: Salvation, 1944-1946”

Karl-Heinz Janßen, “Der 8. Mai 1945 Vor der Kapitulation: Koalitionsgeplänkel”