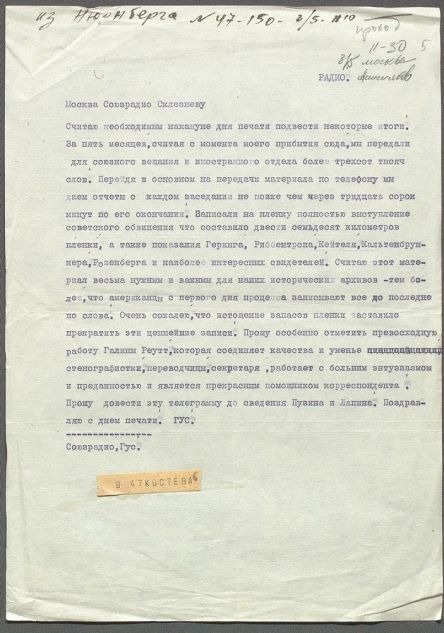

Mikhail Gus was a Soviet international radio journalist, publicist and art critic, who witnessed many of the events of the Second World War. He also worked at the Nuremberg Trials. Residents of the USSR listened to his reports from Nuremberg through special radio devices – so-called black "plates", which were in every apartment and at work places in those years. On 3 May 1946, he sent a telegram to the All-Union radio (the State Committee on Radio Broadcasting) with a report on five months of the work at the trials. And in 1971 he published a book of essays "Madness of the Swastika", in which he described many vivid episodes which he witnessed during the trial.

The radio operators sent their correspondence to Moscow after each session of the Nuremberg Trials, exactly forty minutes after the end of a session, which means twice a day – in the afternoon and in the evening. They made audio recordings of the interrogations of five defendants and several witnesses, using 270 kilometres of tape. Unfortunately, there was not enough tape to record more.

“I consider that this material is very important for our historical archives, especially since the Americans have been recording everything to the last word from the very first day of the trials,” - Mikhail Gus reported. “It's unfortunate that the lack of tape forced us to stop these valuable recordings.”

At the end of his telegram Gus praised Galina Reutt, stenographer-translator and his assistant and congratulated his Moscow colleagues on the upcoming Day of the Soviet Press, which was celebrated on 5 May.

Galina Leonardovna Reutt, mentioned in Gus's telegram, is an extraordinary person. This lady from Moscow lived for almost a hundred years. She was a noblewoman by birth, her mother served as a maid of honor of Empress Alexandra Feodorovna. At the age of three, Galina had a chance to attend a tea party with the imperial family - on the day when the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty was celebrated. Nicholas II was remembered by her as a man with kind eyes, but the girl was more impressed by the spiffy lackeys who were standing behind the chair of each guest.

Due to her knowledge of several foreign languages, Galina began to work at an international broadcasting station at Moscow Radio. And after the war, 35-year-old Galina Reutt worked at the Nuremberg Trials for nine months.

“I was summoned to the chief, and she warned me about an urgent “audition” with a general, - Galina Reutt said, - I had to look good, but I had nothing to wear. I took stockings from one friend, shoes from another, and a coat from a third one. They examined me, and then we packed up our things quickly and flew to Germany in a Douglas plane. All the officers and generals were sitting along the sides, and for us, for the girls, they pulled a tarp on the floor, threw fur coats on it, and we were sleeping during the flight close to each other. It was very cold. All decent clothes were given to us in Germany."

Mikhail Gus recalled his work with Galina in his essay on the Nuremberg Trials, written on the occasion of the 35th anniversary of the event - he was so impressed by this translator. (However, Ilya Ehrenburg, a well-known writer and an eyewitness to Nuremberg, met Galina even before the war. He offered her a position as his personal assistant and secretary, but she refused).

Of course, Galina Reutt was not the only character in Mikhail Gus's essays. He happened to meet a lot of people in Nuremberg. 12 kilometers away from this city in the village of Heroldsberg, he found a son of Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus, Major of the German Army Ernst Alexander Paulus. He told the Soviet journalist about how he ended up in the Gestapo prison with women and children from his family. By Himmler's order, people closest to the commander who had been captured by the Red Army, were taken hostage, because "the head of the Gestapo Müller declared that Field Marshal Paulus headed an army of German prisoners of war that would fight against Germany".

Gus admired prosecutors of the trial, especially Roman Rudenko and British Representative David Maxwell-Fyfe, whom he described as the most powerful interrogator, capable of gutting defendants. And he couldn’t stand defendants` counsels. He described their attempts to improve the reputation of their clients in the following words:

“Provocative maneuvers on the sidelines were mainly directed by Stammer (Otto Stammer – counsel for the defendant Hermann Göring - Ed.), and Seidl, counsel for the defendant Hess, a former Nazi who defended petty thieves and swindlers in the past, was an executor. But in Nuremberg this short, shabby, long-nosed and not at all "Aryan"-looking man is doing "big politics".

During the break, Stammer brainwashes correspondents in the corridor. Near tall Stammer Seidl looks even shorter. He is looking up at Stammer through his glasses, obsequiously learning how to work on the sidelines...

He rushes through the corridors of the court, grabbing the sleeves of journalists and whispers to them:

- I have such a document... especially for you...

And then it turns out that he gives the same promises to all correspondents. Many journalists have refused the “dirty” services of this provocateur”.

The Soviet journalist also gazed at ordinary Germans.

“Accordionist Max appeared in the foyer of the press camp, he was a short stocky man with a revolting face.

There were many Russian songs in his repertoire, he came up to Soviet journalists and played, as they said, right in their ear.

Someone once asked him:

- Max, you were probably held in our captivity?

Max was embarrassed and answered in broken Russian that he was not in captivity.

- How do you know so many Russian songs then?

He got even more embarrassed, said nothing and walked away ... And we never saw him again. And the waiter (the one who visited Nikolaev in 1918) confidentially whispered to me that Max was a notorious Nazi, probably from the SS. (...) Yes, there were different people in that huge human anthill that Nuremberg was like, but it`s better to call it “process”...”.

Sources:

Gus Mikhail Semenovich. Letter to the All-Union radio informing about the work in Nuremberg

3 May 1946 - Original. Typewritten text – The Russian State Archive of literature and arts F. 2808. inv. 1. doc. 92.

Vladimir Mormul “Göring behaved arrogantly”. The “Angle of View” newspaper, 13 January, 2021

Mikhail Gus “Madness of the Swastika”. – “Soviet writer”, Moscow, 1971

By Julia Ignatieva