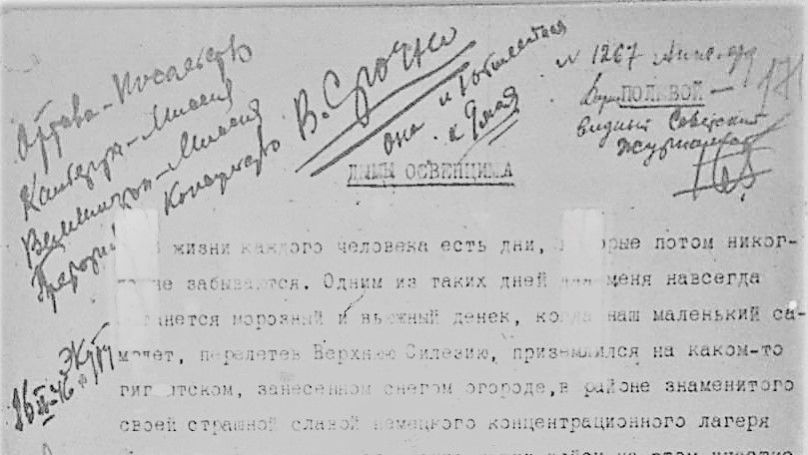

Pravda’s special Nuremberg correspondent, the celebrated writer Boris Polevoi (who would soon shoot to fame in the Soviet Union for his book “The Story of a Real Man”) knew much more about Auschwitz than many other eyewitnesses at the Nuremberg trials. He visited the camp two days after it had been liberated by the Red Army in January 1945 and interviewed prisoners and witnesses, afterwards writing a memo about it to the Political Department at the Front. On 15 April 1946, he published his impressions of the examination of Rudolf Höss, the former commander of Auschwitz Extermination Camp, by the Nuremberg tribunal on the same day in an article for the Soviet Information Bureau. The authors of “Nuremberg: Casus Pacis” found the article in the archives of Sovinformburo. The full version of Polevoi’s article about Auschwitz is published for the first time.

‘The Smoke of Auschwitz’

“Everyone has days in their life that they never forget. One of those days for me will always remain a frosty and blustery day when our little plane, having flown over Upper Silesia, landed on a giant snow-covered vegetable garden, in the vicinity of the infamous German concentration camp of Auschwitz. In those days, the advance of our forces in this area unfolded broadly and irresistibly, like a torrent of spring water, sweeping away any German attempt to halt and consolidate their hold on the intermediate lines. [Crossed out] The Germans fled, throwing aside anything and everything, not having time to carry off their looted riches, nor burn the archives, nor cover the traces of their bloody atrocities. When our plane was still circling above the giant concentration camp, looking for a landing spot, I remember [crossed out] thousands of people in strange striped uniforms ran towards us on all sides. They stumbled, fell, jumped to their feet and ran again, panting, waving their arms, laughing and crying at the same time.

And from them, these martyrs of Auschwitz, rescued by the Red Army from death, we learnt what kind of smoke lingered over the camp, enveloping the area and filling our chests with a heavy stench. The Red Army was so powerful a presence in this place that a number of SS-men from the camp fled in the morning, having hastily managed to blow up the gas chambers and some of the ovens - although some remained intact and piled high with corpses which continued to smoulder, poisoning the air with their smoke.

Auschwitz was the most perfect embodiment of heinous and inhuman German fascism a building can be.

It was Himmler's pride and joy, and he had zealously supervised its construction from his Berling lair and stocked it with technical equipment, directing and supervising the work of this gigantic death factory and often, as the prisoners told me at the time, going there with his entourage or with a visiting group of distinguished Nazi officials to amuse himself by watching dogs baiting people and observing the mass executions, carried out there by all the methods invented by fascism: from the simultaneous firing of machine guns on large crowds to killing with "Zyklon B" in giant gas tanks; from the practice of shooting live people running through the field on Sundays to the killing of victims by electrocution.

Accompanied by a large crowd of people in striped trousers and jackets, people so pale and thin, exhausted to the point where they swayed like shadows in the wind, we walked around this cursed place, probably the most terrible place on earth. Yes, it was perhaps the height of the Nazi fantasy, the highest point Hitler had reached in his misanthropic drive to “dehumanise” the world. We were shown an extermination camp - an entire railway junction that, at the height of Auschwitz, received two or three pairs of long, full freight trains a day with cars jammed full of people – the raw materials for this gigantic death factory. We were shown a five-metre concrete wall, scarred with machine guns and automatic rifles, against which the mass executions were carried out. This Nazi shooting gallery was equipped with the latest technology, the concrete ground was fitted with drains and grates for draining human blood and there were rubber hoses to wash it off the walls. We were shown a huge, long building of gas chambers. They had been blown up, but on the remaining walls we could still read the inscriptions “Changing Room”, “Disinfecting Room”, “Bathhouse”, “Delousing Station”. They were indeed cleverly disguised as bathhouses. They even had fake taps, with neither warm nor cold water ever running from them, and showerheads on the ceiling, which, although they worked, were not there to wash people but to wash their blood off the floor. We were shown a whole town of dog cages. Dogs were running and howling and biting, hundreds of huge dogs trained to attack people. We saw secret warehouses of "waste", mountains of jaws and crowns, gold bridges torn from the mouths of murdered victims. We walked around the huge warehouses piled to the ceiling with women's hair, both lying in heaps and already sorted and packed for shipment to Germany. It was here that we heard for the first time about SS-Obersturmbannführer Rudolf Franz Ferdinand Höss, the builder and first commandant of Auschwitz. [Crossed out]

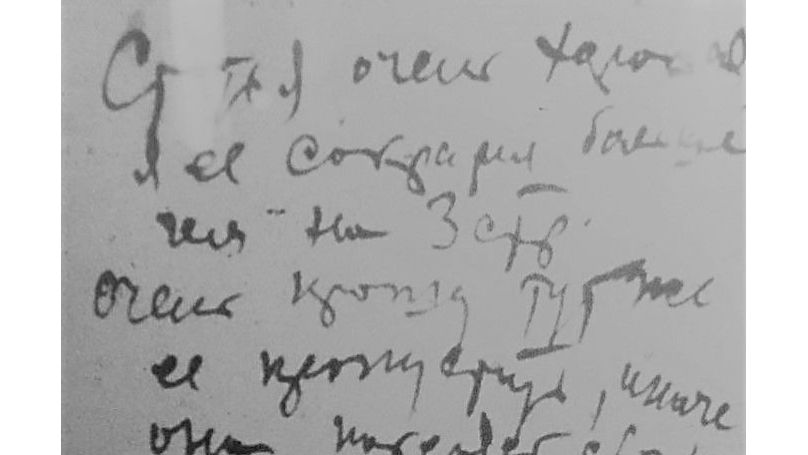

The people in striped uniforms who led us through this corner of Nazi hell pronounced the name with horror and disgust. It was well into the evening when we reached the so-called “Gypsy Block”. Here, on the concrete floor, beside a steam pipe, the famous Belgian art historian, the 60-year-old Jean Pernas, was dying. His comrades asked us Red Army officers and Soviet journalists, to approach him to hear his last words. This dark-skinned human skeleton was already departing and the man who acted as our interpreter was forced to bend close to his mouth to hear his words. Here they are. I have memorised them:

– “Avenge us! Find and avenge us, for the smoke of Auschwitz which they wanted to use to blot out the Sun from humanity. Remember their names and avenge us.”

The names of the other executioners of Auschwitz have been forgotten, but Höss's name sticks in the memory, as well as the whole day of the visit to this corner of Nazi hell. It was here, in Nuremberg, many months after that day that we got to see this creature of Nazi hell. Like many Nazi criminals, Rudolf Franz Ferdinand Höss got a false passport after the defeat of Nazism, changed his place of residence, dyed his hair and worked on a farm somewhere near Nuremberg as an agricultural labourer until recently. He tilled other people's gardens and hoped that when things quietened down and tempers had cooled, he would find his secret hoard of gold, cast from the dental crowns and bridges of his countless victims and live somewhere in happy and prosperous retirement. Here, near Nuremberg, he was exposed and arrested.More to read

And now this ineptly and hastily disguised Hitler's wolf is standing on the witness stand, giving evidence in the case of his former boss Ernst Kaltenbrunner. The world press eagerly awaited the appearance of this chief executioner of Auschwitz, who, by his own admission, had gassed, shot and starved some three million people. They were apparently expecting something special, supernatural and so everyone was shocked when a small, unsightly, grey-haired man entered the hall and, taking his place at the microphone, began to give his testimony in the same grey, steady, normally calm voice. He spoke as if he were talking not about one of the greatest crimes in the history of mankind, not about the extermination of millions of people he systematically carried out year after year, but about harvesting vegetables from a garden or felling a forest.

This mundane, unassuming appearance, the calm equanimity of his voice, is perhaps the most frightening thing about him. These were the kind of obedient officials who were executors of their evil will and who were raised, nurtured and inculcated by Fascism. This was the apotheosis of the fascist figure, the ideal of the representative of the "master race" to which all those Hitlers, Görings, Hösses, Himmlers and Rosenbergs guided the German people. The extermination of millions of innocent people was an everyday occurrence for him, which he, in his own words, considered no worse than any other job or position in the Nazi Reich. Mass public executions, terrorising people with dogs - all innocent amusement for his men, who were eventually bored with the prosaic extermination of prisoners in the gas chambers - practised day in and day out. The SS had to let the men loose, to tickle their nerves. After all, it did not matter how a person was brought to the chimney. Both Hitler and Himmler, Kaltenbrunner and he, as the executor of their will and orders, encouraged their men to explore new and effective means of mass murder and to invent productive machines and assembly lines for the destruction of human bodies. The terrifying smoke of Auschwitz, in his opinion, was no worse than that of any other factory or plant operating for the needs of the Nazi Reich.

And even here, holding his answer in the face of world justice for freedom-loving nations, he, this perfect example of a German fascist, a member of the Nazi Party since 1923 and a volunteer member of the SS since 1934, a murderer-criminal in the distant past and a fascist and executioner of millions in the recent past, finds nothing special in his terrible work and coldly expressed it via a microphone:

“Of course, I cannot give the exact figure, but at Auschwitz I estimate that at least 2,500,000 victims were executed and exterminated there by gassing and burning, and at least another half million succumbed to starvation and disease making a total dead of about 3,000,000. Yes, yes, that figure should not be considered an exaggeration”.

And perhaps for a moment having forgotten where he stands, mentally returning to the past, he suddenly begins to boast, to brag about the scale and perfection of the means of human extermination he employed at Auschwitz. Responding to the representative of the American prosecution, Colonel John Amen, he said:

“We were undoubtedly able to develop a better extermination technique than in the other camps. We used all their best achievements and added a lot of our own. They used different gases for gassing people, not very effective in general. I was the first to use Zyklon-B. It's a crystalline strong acid. A beautiful poison. People die in 10 to 15 minutes exposed to its vapour. In Treblinka, in Belzec, in Buchenwald, they had small gas chambers, fitting no more than 200 people. You had to go to a lot of trouble to fill them. I had each cell with a capacity of 2,000 people at a time, and if you wanted to, you could get more in without crowding. In other camps, people got off the train and already knew where they were going. Well, of course, there was the noise, the crying, the screaming: mothers hiding children in their clothes, not giving them away. It often led to riots. But we had nothing like that. Everything was well disguised as baths, lavatories, disinfecting rooms. People got off the train and genuinely thought they had been brought to work. They were eager to wash up after the journey. They deposited their clothes neatly on a hanger and received a number. Valuables were deposited separately. They only started to guess what was about to happen to them when the doors were bolted shut and the gas was turned on. They shouted, of course, but there was nothing they could do to stop it. In terms of extermination techniques, we were clearly in top spot”.

Boasting wildly, Höss said that it was he who managed to organise the proper use of the waste products of his gigantic death factory: women's hair, clothes, shoes of the executed, a special team was even established to tear gold crowns, jaws and bridges from the mouths of those who had been slaughtered. All this generated a considerable income in gold for both the Reich and the executioners.

I listen to the rasping of [Höss’s] calm and business-like voice, and think what kind of system, environment, ideas there must be in which such monsters could be born, brought up and nurtured. I recalled the smoke of Auschwitz. I recalled its prisoners and their dying entreaties. And I wanted to say to those half-dead men in striped uniforms, who had been rescued from the fiery ovens by a miracle, that their murderer has not and will not escape punishment, and nor will all those who cultivated him, who directed his bloody hand who thought up all these Auschwitzes and Mauthausens, that there is no place for them on earth, there is none and will be none”.

***

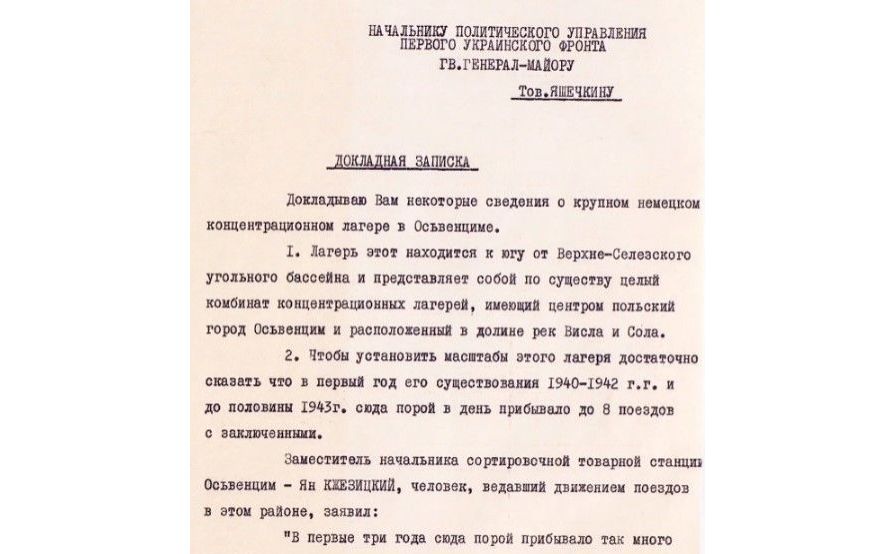

Internal memo by Lieutenant-Colonel Boris Polevoy, correspondent of Pravda newspaper, to the Chief of the Political Department of the 1st Ukrainian Front, about Auschwitz concentration camp, 29 January 1945.

"To the Chief of the Political Department of the 1st Ukrainian Front

Major General Comrade Yashechkin

Memo

I report to you some information about a large German concentration camp at Auschwitz. I. This camp lies to the south-east of the Upper Silesian Coal Basin and in effect forms an entire complex of concentration camps, centred in the Polish town of Oświęcim (Auschwitz) and situated in the valley of the Vistula and Soła Rivers.

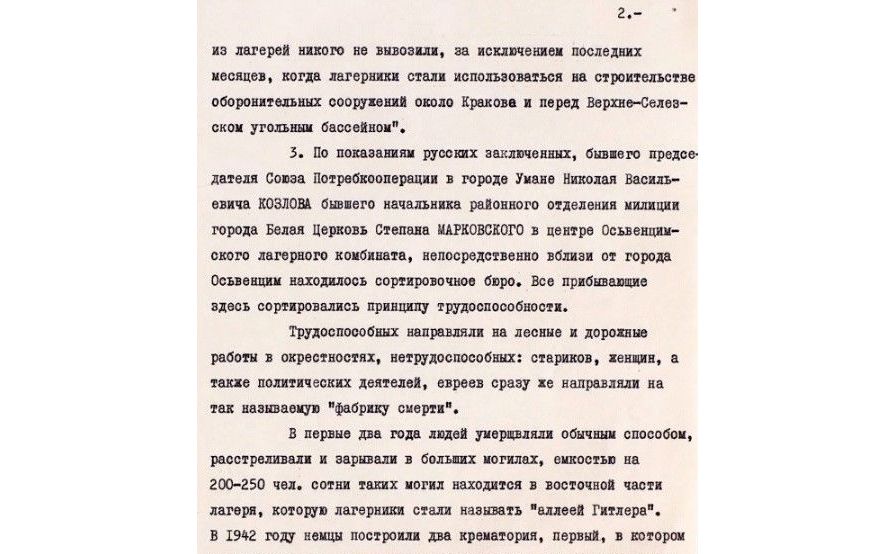

II. To ascertain the population of the camp, one must realise that during the first years of its existence, from 1940 until mid-1943, up to eight prisoner trains arrived here per day. Deputy Chief of the Freight Station Auschwitz, Jan Krzezinski, the person in charge of train traffic in the area, said:

“In the first three years, there were so many trains with prisoners that our freight station did not have time to process these trains, and the deputy chief of the freight station, Kazimierz Kontusz, was sent to Auschwitz for failing to do so. We usually had six to eight trains a day. If we assume that there were up to 30 cars in a train, and that the Germans were stuffing up to 50 people into each car, it would give us an approximate figure for the daily inflow of prisoners to the camp. Notably, no one was ever taken out of the camp, except during the last few months, when the camp prisoners were forced to build defensive works near Krakow and in front of the Upper Silesian Coal Basin”.

III. According to the testimony of Russian prisoners, Nikolai Vasilievich Kozlov, former chairman of the Uman Consumers’ Cooperative Union, and Stepan Markovsky, former head of the Bila Tserkva district police station, there was a segregation bureau in the centre of the Auschwitz camp industrial complex, just outside the town of Auschwitz. All those arriving here were categorised according to their ability to work.

The able-bodied were sent to the forest and road works in the surrounding area; those deemed unfit for work - the elderly, women, politicians, the vast majority of whom were Jewish, were immediately sent to the so-called “death factory”.

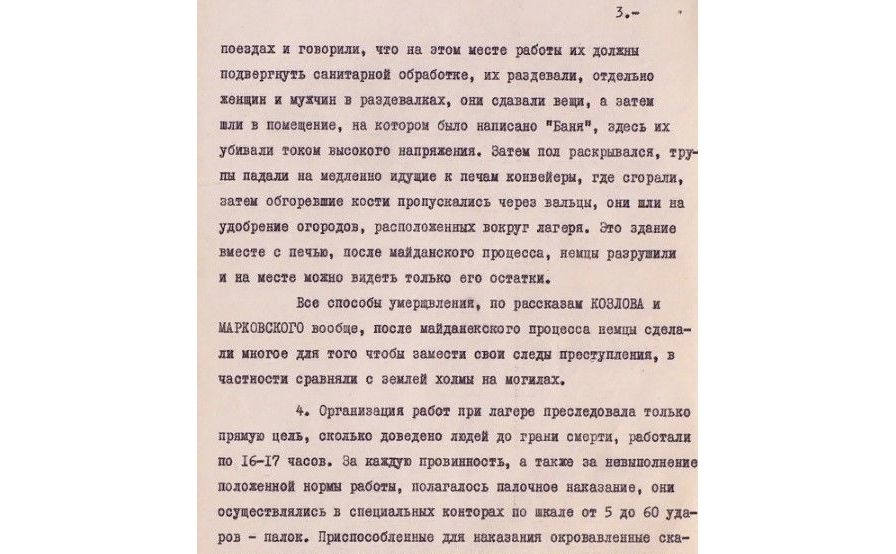

During the first two years, people were executed in the usual manner, shot and buried in large graves with a capacity of 200 to 250 people. Hundreds of such graves were located in the eastern part of the camp, which the prisoners called “Hitler's Alley”. In 1942 the Germans built two crematoriums: the first, where corpses were burnt just as at Majdanek, resembled a large lime-burning factory on the outside. But the second was a so-called “assembly line of death” - it was a long building, almost half a kilometre in length. At the end of it, there were mining furnaces heated with hot coal gas - the temperature in the furnaces reached 800 degrees - and it took eight minutes to burn corpses in them. From the furnaces to the north there was a lateral building with metal flooring, divided into separate cabins. Prisoners were brought by train and told that they were to be sanitised at this place of work. They were undressed in separate male and female changing rooms, they handed in their belongings and then went to a room marked "Bathhouse". Here they were killed by a high-voltage current. The floor would then open up letting the corpses drop onto conveyor belts that slowly made their way to the ovens, where they would be burnt, then the charred bones would be passed through rollers and would be used to fertilise the vegetable gardens around the camp. This building, together with the ovens, was destroyed by the Germans after the Majdanek trials and only its remains can be seen at the site.

After the Majdanek trials the Germans went to great lengths to cover up the traces of the crime, in particular levelling the mounds of the dead so that they would be flush with the ground.

IV. The organisation of work in the camp had only one direct objective - to drive as many people to death by working them 16 to 17 hours a day. Each offence, including not fulfilling the daily assigned work rate, carried punishments ranging from five to 60 strokes in special offices. I saw with my own eyes the blood-stained punishment benches lined with zinc and straps to bind hands and feet, the steel canes covered in leather, the iron sticks, the whips with steel cords drawn into them.

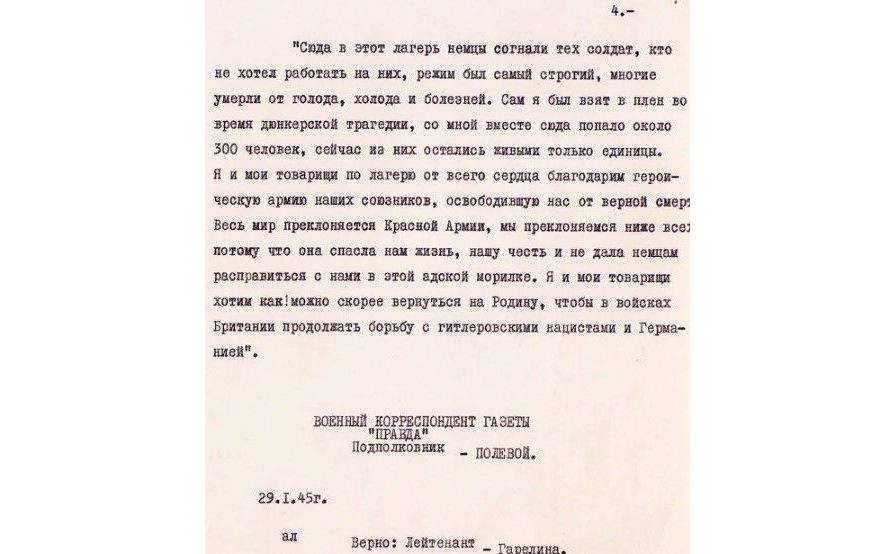

V. Not far from Auschwitz there was an English and Canadian POW camp near the village of Babice. When this camp was liberated, there were several thousand soldiers and officers of our Allied armies there. In a conversation with me, John Umit of Birmingham said:

“The Germans drove those soldiers who did not want to work for them here to this camp, the regime was the strictest; many died of hunger, cold and disease. I was taken prisoner during the Dunkirk tragedy; about 300 men were taken here with me, only a few of them remain alive now. I and my campmates thank with all our heart the heroic army of our Allies, which has freed us from certain death. The entire world praises the Red Army, we revere the Red Army far above all because it has saved our lives, our honour and prevented the Germans from massacring us in this hellish slaughter chamber. I and my comrades want to return to our homeland as soon as possible, to join the British forces, to continue the fight against Hitler's Nazis and Germany”.

Lieutenant Colonel Boris Polevoi, war correspondent of Pravda newspaper

29 January 1945”