Death of Soviet driver still unsolved.

The Nuremberg Trials covered a spectrum of crimes, from those committed by the Nazi top brass to lowly foot soldiers, while a murder even happened in Nuremberg itself.

In December 1945, a Red Army soldier called Comrade Buben – the chauffeur of a counterintelligence chief – was murdered just outside the Grand Hotel. To this day, the case remains unsolved.

The Only Decent Place in Town

The evening of 8 December at Nuremberg's Grand Hotel was, as usual, lively as guests from all over the world rubbed shoulders. “The hotel was badly damaged by American bombing raids,” Soviet interpreter Olga Svidovskaya (according to other sources, Sviridova) said. “One part of it, more or less rebuilt and brightly lit, housed a lobby with a revolving door and a restaurant where half-starved Germans entertained the Allies as best they could. It was pathetic, but there was essentially nowhere to go.”

Shortly before midnight, a gunshot rang out; a driver who was waiting for one of the revellers was murdered right outside the hotel.

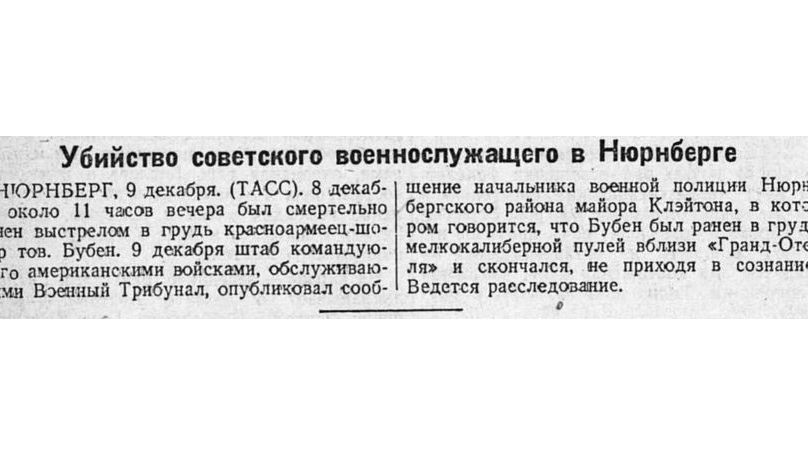

On 12 December a short article appeared in the Pravda newspaper:

“Nuremberg, 9 December (TASS). On 8 December, around 11 pm, a Red Army driver, Comrade Buben, was mortally wounded. On 9 December the headquarters of the commander-in-chief of the US forces serving the Military Tribunal issued a report by the military police chief of the Nuremberg district stating that Buben had been shot in the chest with a small-calibre bullet near the Grand Hotel and had died without regaining consciousness. An investigation is underway.”

Night Shot, Revolving Door

There is little that we know for certain. Buben used to drive Mikhail Likhachev, head of the Special Investigation Team of the SMERSH Counterintelligence Department, who often dined at the Grand Hotel. He would wait for his chief in the car and never enter the restaurant.

Most of the details came from Svidovskaya, Likhachev's interpreter, and her colleague Elisaveta Stenina-Schemeleva. It is worth noting that neither of them witnessed the crime and relayed the story on hearsay.

“One day we – namely Likhachev, [SMERSH Senior Investigator Pavel] Grishaev, [SMERSH Senior Operative] Boris Solovov and I – were going to have our usual dinner at the Grand Hotel, but I had some business and decided to stay at home,” historian Alexander Zvyagintsev quotes Sviridova's (Svydovskaya) memories in the book The Nuremberg Alarm. “Likhachev and his company went to Nuremberg in a very conspicuous limousine – a black and white Horch with red leather interior said to be from Hitler's garage. Likhachev used to sit in the front, to the right of the driver. Before reaching the Grand Hotel, Grishaev and Solovov asked to stop the car, as they decided to walk the rest of the way. After hesitating for a few seconds, Likhachev joined them. A moment later, someone wearing the uniform of an American army private jerked open the front right door of the car, which was parked outside the Grand Hotel, and shot Buben at point-blank range. I believe that the victim of the attacker was supposed to be Likhachev, as he must have thought that Likhachev was sitting in his usual seat. The mortally wounded Buben managed to say: 'I was shot by an American'.”

Svidovskaya's memoirs have not yet been published, although some quotes have circulated in books and the press. Journalist Vladimir Abarinov, having read the interpreter's memoirs, in his article “Death at Nuremberg: A White Spot in the Major Trial” quotes her words about Buben's death in a slightly different form. According to this interpretation, Likhachev did not go to the Grand Hotel at all that evening, Grishaev and Solovov got out of the car right in front of the hotel. There were no witnesses to the murder – Svidovskaya specifies that “one could hardly see behind the row of parked cars.” Nor does she say anything about the American uniform. Buben's last words are more expressive in her retelling: “An American shot me.”

Elisaveta Stenina-Schemeleva described the episode to Abarinov in her own words. She said the mortally wounded Buben entered the revolving door of the hotel shouting: “And we call them Allies!” before collapsing on the floor.

In any case, both women were merely retelling what they had heard from the SMERSH officers.

There are many contradictions in these stories. Was Likhachev in the car that evening? Did Solovov and Grishaev get out of the car just outside the hotel or before reaching it? Why would Soviet officers be walking in the evening in a bombed-out, devastated city, and in the shadiest district to boot? Did Buben die on the spot or did he manage to get into the hotel? Finally, who would want to kill a driver?

Scandals, Intrigues, Investigations

The background of this detective story gets a little clearer if one knows that there was a rivalry between the two Soviet security agencies at Nuremberg. The investigation, including the preliminary interrogation of the tribunal's defendants, was handled by a prosecution team headed by Georgi Alexandrov, who reported to the USSR’s chief prosecutor, Roman Rudenko. And operational matters (law enforcement) were handled by a special investigation team of the Main Department of Counterintelligence, SMERSH, headed by Mikhail Likhachev.

There was friction between them and, as Aleksandr Zvyagintsev wrote, “some members of the group were suspicious of each other, exchanged accusations, and sometimes things went even further.” For example, even before the trial began, the counterintelligence officers reported to Moscow that Aleksandrov "weakly parried" the anti-Soviet attacks of the defendants. He had to defend himself in writing to the USSR Prosecutor Konstantin Gorshenin, saying that there had been no attacks by the defendants either against the Soviet Union or against him personally, and these groundless accusations only hindered the work.

However, the story didn’t end there. According to the assistant prosecutor for the USSR, Lev Sheinin, Likhachev proved to be an arrogant man from his first days in Nuremberg and subsequently rubbed people up the wrong way.

“And so it went to the point,” wrote Sheinin, quoted by Zvyagintsev in his book, “where Likhachev got a young interpreter living in the same house as us involved in cohabitation, and she became pregnant. Likhachev forced her to have an abortion and, having found a German doctor, forced him to perform the operation.”

According to Zvyagintsev, after Buben's murder “there were rumours of an assassination attempt on Rudenko, but the more likely target was Likhachev. The mission he headed was carrying out important work in Nuremberg. There was every reason to believe that someone wanted to intimidate the counterintelligence officers while eliminating their leader.”

One cannot rule out that the murder could have been committed by German saboteurs in order to provoke a conflict between the Americans and the Russians. However, considering the conflicts between the prosecution team and SMERSH, personal motives cannot be ruled out.

Reports, Arrests, Executions

According to Sheinin's recollections, Rudenko reported everything that happened to Gorshenin, who was in Nuremberg at the time. The latter, in turn, passed the information on to the Party Central Committee and to Viktor Abakumov, head of SMERSH. Likhachev was recalled from Nuremberg and arrested for ten days.

A few years later, Likhachev's career was on the rise: he became deputy head of the investigative unit for important cases at the USSR Ministry of State Security. In 1952, he was tasked with handling the fabricated case of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, in which Sheinin was one of the suspects. Likhachev forced what he believed to be compromising evidence out of Sheinin. The latter would not be released until December 1953, after Stalin's death.

A year later, Likhachev himself would become a victim of repression. In December 1954, he, along with Abakumov and other MGB leaders, would be convicted of abuse and executed by firing squad.

However, the question of who shot Red Army soldier Buben and why remains a mystery. Perhaps the answers are just lying dormant in the archives of the secret services.

Based on the book The Nuremberg Alarm: Reporting from the Past, Addressing the Future by Alexander Zvyagintsev and the article “Death at Nuremberg: A White Spot in a Major Trial” by Vladimir Abarinov.