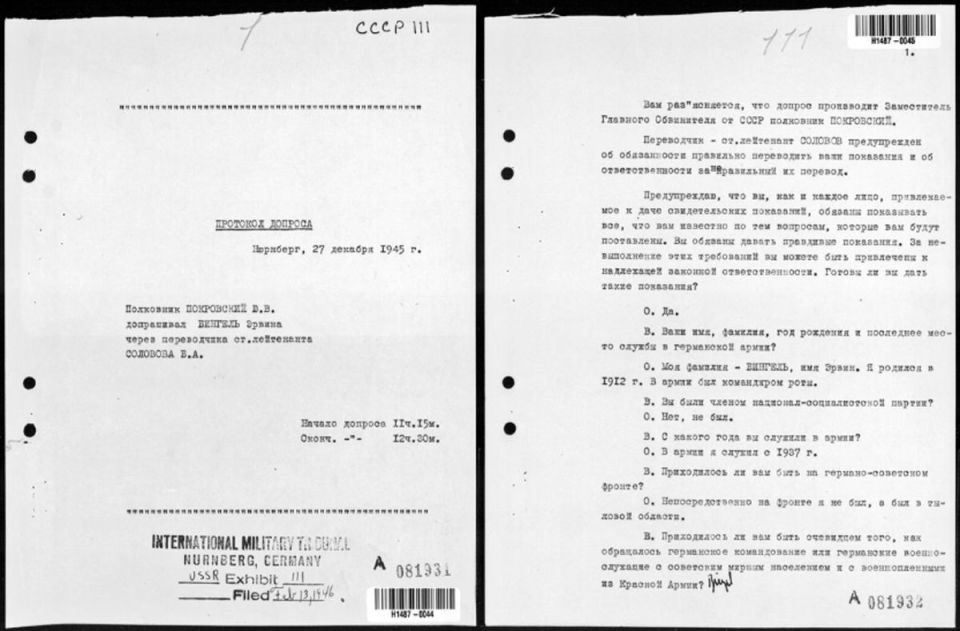

The editors' team of the “Nuremberg: Casus Pacis” project has studied a unique document recently published on the Stanford University website among the materials submitted by the Soviet side to the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg.

The document is part of a large collection of archival materials in Russian, recently digitised and made available to the public. The transcript of the examination was included in the Tribunal's files as official evidence but was not read out at the sessions. The reason may have been that the document referred to the genocide of the Jews, a subject that the Soviets tried not to emphasise when speaking about the victims of all the peoples of the USSR. Furthermore, it can be assumed that the representatives of the Soviet prosecution considered it unnecessary to emphasise the role of the Ukrainian police in this and similar punitive operations and massacres.

Quote:

– In the morning of the day on which the Jews were shot, I was on guard duty with my men, as usual, on the main roads leading to the airfield. Then I heard a mournful singing coming from the city, and I felt that something was restless in there. The singing kept coming towards the airfield. I wondered what it could mean. (...)Suddenly, large groups of people appeared on one of the roads. There were men and women with babies in their arms. The whole procession headed towards the open field in front of the airfield.

– Did people walk on their own or did guards lead them?

– The Ukrainian Police were guarding the people.

– And who sang the songs - those people or not?

– Yes, they were the ones singing the songs.

– What kind of songs did they sing?

– These were Russian folk songs.

– Happy or sad?

– They sang "Stenka Razin" and other sad Russian folk songs. None of us, however, could have imagined what this procession was supposed to mean. Only when these endless columns of people reached the site in front of the airport did trucks appear from the city. A field gendarmerie and a few policemen emerged from these vehicles.

– Do you mean those Ukrainian Police units that were in the service of the German command?

– Yes.

(…)

All the incoming people were distributed in groups along the moat and some columns were ordered to move closer to the tables. Some of the commanders were seated at the tables along with Ukrainian Police officers. People approached the first table and were seen undressing. At another table, they would hand over valuables, jewellery that they had with them. Once they were completely naked, they were brought to the moat and placed about 2 metres from the edge of the moat. Individual unit commanders would give the order and people would be shot and then dumped into the pits.

– People were shot in groups?

– People were shot both in groups and individually with submachine guns. When the first round was over, the second round was already completely undressed. (...) After that, all the men were rounded up and ordered to cover the shot people – some still showing signs of life – with bleach and then use shovels to spread a thin layer of earth. Afterwards, they were subjected to the same fate as their previous comrades they had buried.

– How many people were shot before your eyes?

– I saw 23,000 people executed.

– Did you observe any case of resistance from those waiting to be shot?

– They offered no resistance but followed their fate obediently.

Commentary by Sergey Miroshnichenko, a lawyer and translator of the Nuremberg Trials Stenograph:

On 27 December 1945 Colonel Yuri Pokrovsky, Deputy Chief Soviet Prosecutor, interrogated the German officer Erwin Bingel (his rank was not specified) at Nuremberg. The officer testified that, first, he had witnessed the mass shootings of Jews in the town of Uman, Cherkasy Oblast, and, second, the mistreatment of Soviet prisoners of war in a makeshift temporary camp.

The text of this interrogation was the official evidence, which was added to the case file under registration number USSR Exhibit No 111. However, during the Soviet prosecutors' speeches at the Nuremberg trials, neither the document itself nor extracts from it were made public. Nevertheless, the judges were obliged to consider it because it was in the case file.

The document reflects the impressions of an officer who had to provide a cordon near Uman airfield during the organisation of the mass shooting of local Jews “in the winter of 1941, at the beginning of November”. He described how, while on duty, he heard Russian songs approaching and found a large group of Jews coming (so he judged them by their appearance). The prosecutor even specified what songs the Jews were singing, and Bingel replied that Russian folk songs, sad ones – he remembered a song about Stenka Razin.

These Jews were led to the airfield, where anti-tank trenches had already been prepared. Trucks drove up, tables and chairs were placed on which members of the Einsatzgruppen and the Ukrainian auxiliary police, who, so to speak, "ensured order" at the place of execution, seated themselves. The Jews handed in their clothes and valuables in front of these tables and went to the ditches. Women and children were shot first, they fell into the pit, then the Jewish men covered the first layer of the dead with lime and stood on the edge of the ditch themselves. They, too, were shot. Overall, according to Bingel, 62,000 people were shot in Uman, of whom 23,000 – before his eyes.

The second part of the interrogation concerns the treatment of Soviet POWs. It describes scenes when the POWs did not have enough food (instead for 70,000 people food was cooked for only 2,000), there were constant fights. German soldiers killed Soviet POWs to break up the fighting, and some died of starvation on the spot.

In my opinion, it was because the officer described the involvement of the Ukrainian police in the extermination of the Jews that the document was included in the case file but was not made public. The Soviets talked a lot about Nazi atrocities but tried not to emphasize the extermination of the Jews. All the Acts of the Extraordinary State Commission refer primarily to "Soviet citizens," but here we are talking specifically about the Jews.

What is the value of this document? Witnesses at the Nuremberg Trial said that they were either unaware of what was happening to the Jews, or that they had not seen or participated in it. And here is a very valuable confession, not just of a civilian specialist, but of a German officer, who during the interrogation even expressed his willingness to testify about these facts at the Tribunal. That is worth a lot! Moreover, the interrogation took place not in the Soviet Union, but in Nuremberg, in the American zone of occupation, the officer was not threatened and testified voluntarily.

Another important detail: Uman used to be one of the most important Jewish centres in the Russian Empire before the revolution. Rabbi Nachman, the founder of a movement in Judaism called Breslov Hasidism or the Breslov movement, was buried here, and pilgrims have been flocking to his grave since the 1820s. Of course, during the Soviet era, pilgrimages ceased, but locals still worshipped the rabbi's grave. And suddenly these people – certainly rooted in Jewish customs and traditions – are singing Russian songs! This is an unexpected and surprising manifestation of the blending of different cultures.

By Daniil Sidorov and Lesya Orlova

Source: https://nuremberg.media/dokazatelstvo/20211029/284406/Evrei-shli-na-smert-i-peli-russkie-pesni.html