On 3 May 1946, the International Military Tribunal for the Far East began its work in Tokyo, the capital of Japan. It was the last joint “political project” of the USSR and the West, before the Cold War began. Experts of the “Nuremberg: Casus Pacis” project explain the difference between the Tokyo Trial and the Nuremberg Trials, and how it happened that in Japan it was not top officials, but their subordinates who were convicted for the crimes.

From Holland to the Philippines

In the summer of 1945, at the Potsdam Conference, the leaders of the victorious countries decided to hold an open trial over the main war criminals not only in Europe but also in Southeast Asia. Paragraph 10 of the Potsdam Declaration stated: “all war criminals, including those who have visited cruelties upon our prisoners, must be severely punished”.

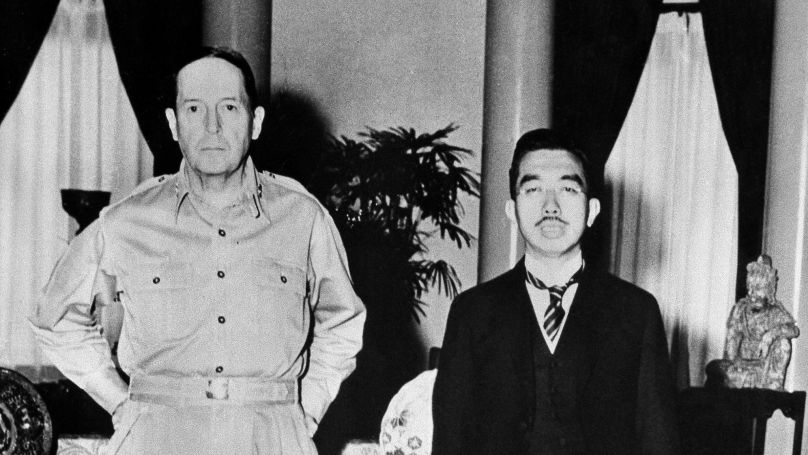

In mid-January 1946, General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers during the Allied occupation of Japan, issued a decree establishing a tribunal for Japanese war criminals.

The prosecutors were fom 11 nations affected by the actions of militaristic Japan: the United States, the USSR, Great Britain, China, France, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, Holland, India, and the Philippines.

Sir William Webb, a judge of the Supreme Court of Queensland and the High Court of Australia, was appointed president of the tribunal, and Joseph Keenan, US Assistant Attorney General, – the chief prosecutor. The Soviet Union was represented by Major General of Justice Ivan Zaryanov, a member of the Military Collegium of the Supreme Court of the USSR, as the Justice of the Soviet Union; Sergei Golunsky, Head of the Treaty Law Department of the USSR Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Corresponding Member of the USSR Academy of Sciences, – as prosecutor; and Alexander Vasiliev, State Councilor of Justice and Moscow Prosecutor who succeeded Sergei Golunsky.

The Americans Took the Lead

"The Tokyo Trial incorporated the most important provisions that were formalised during the work of the Nuremberg Trials, but the processes were significantly different from each other,” Alexander Mikhailov, a historian at the Victory Museum, commented. “For example, unlike in Nuremberg, there was no radio broadcasting in Tokyo; the charter of the trial was not developed jointly but exclusively by American attorneys in accordance with Western (Anglo-Saxon and continental) legal and procedural norms”.

The work of defence was structured differently. At the Nuremberg Trials, each defendant used the services of one German defence counsel and a staff of assistants, but at the Tokyo Trial, a defendant could have several defence counsels. In total, 28 defendants were provided with 79 Japanese defence counsels and 25 American ones, who were necessary since the Japanese had little knowledge of Western legal standards.

At Nuremberg, all verdicts were considered collegially but at the Tokyo Trial, General Douglas MacArthur had broad powers. “He had a right to appoint or replace the president of the court, as well as the chief prosecutor, members of the tribunal and their representatives. MacArthur could even vary the sentence”, Alexander Mikhailov noted.

The Nuremberg Trials were held in four languages: English, French, Russian, and German. In Tokyo, only Japanese and English were the official languages of the tribunal – the transcripts of the trial were recorded in these languages.

“Thus, Americans took key positions in the Tokyo Trial. They sought to demonstrate their key role in defeating Japan, especially in the context of the outbreak of the Cold War,” Mikhailov emphasised.

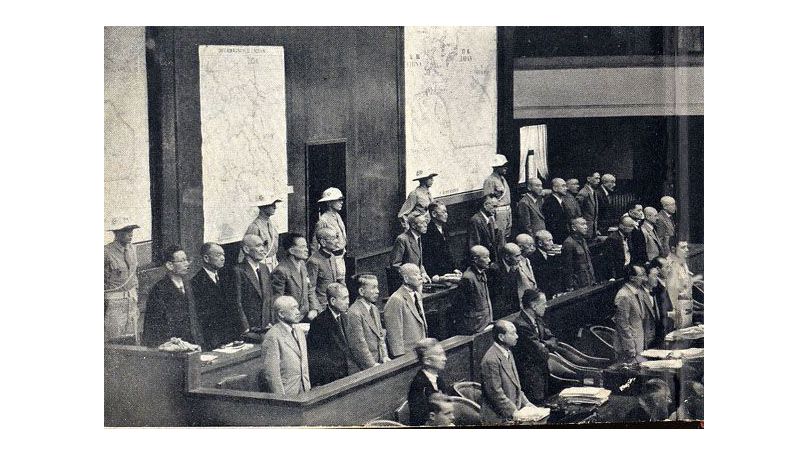

Emperor – Above Any Criticism

The deterioration of Soviet-US relations after Winston Churchill's Fulton speech on 5 March 1946 affected the list of war criminals for the Tokyo Trial. The Americans tried to dictate their terms but were forced to make concessions to the Soviet Union. After much deliberation, the parties put 29 persons on the dock, but former Japanese Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe took poison just before his arrest. As a result, 28 people were put on trial.

There was a separate debate about whether or not Hirohito, Emperor of Japan, and members of his family should be put on trial. Hirohito originally headed the list of criminals. But in Japan the Emperor is a sacred figure: it is the only country in the world where the ruling dynasty has not been abolished since at least the beginning of the 4th century. Even after Hirohito renounced his divine origin on 1 January 1946 at the request of the Americans (albeit very evasively and ambiguously) he remained the most important symbol of the nation. To put him on trial was to provoke a major political crisis and possibly a military uprising. Therefore, the Allies excluded Hirohito's name from the list of defendants.

All members of the imperial family received immunity along with him. This was a much more controversial decision. While Hirohito as constitutional monarch was largely silent at cabinet meetings, many of his relatives held key positions in the army and navy during World War II and committed war crimes.

The commanders of Japanese units and research institutes that produced bacteriological and chemical weapons also escaped prosecution. During the war, the 731 Unit of the Imperial Japanese Army tested them on humans – the experiments on the test subjects were as atrocious as those carried out in Germany.

“The American Military Command struck a deal with the developers of weapons of mass destruction, obtaining in return huge amounts of information on the development of these weapons. This was absolutely unacceptable to the Soviet representatives”, explained.

In December 1949, 12 Japanese Kwantung Army soldiers who had used bacteriological weapons were convicted by the Soviets at the Khabarovsk War Crimes Trial.

Suicides, Madmen, and Other Defendants

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East held 818 public sessions and 131 courtroom sessions. The tribunal examined 4,356 items of documentary evidence and 1,194 testimonies on crimes committed by the Japanese military and political leaders. Almost half of these testimonies were heard during the sessions.

“There were initially plans to include 55 counts in the indictment, but only 10 reached the verdict. The final verdict was handed down by the judges amid sharp disagreements and contradictions between the participants of the tribunal”, Alexander Mikhailov said.

On 12 November 1948, the Tribunal at Tokyo sentenced 25 Japanese war criminals. Seven men were sentenced to death by hanging: General Hideki Tojo, former Prime Minister and Minister of War, General Seishirō Itagaki, former War Minister, Koki Hirota, former Prime Minister and Foreign Minister, as well as Generals Iwane Matsui, Kenji Doihara, Heitarō Kimura, and Akira Mutō.

The other 16 defendants were sentenced to life imprisonment. Former Foreign Minister Shigenori Tōgō received a 20-year sentence, while Former Foreign Minister and Japanese Ambassador to the USSR, Mamoru Shigemitsu, was sentenced to 7 years in prison.

None of the defendants was acquitted at the end of the Tribunal, but three were dropped from the trial. Philosopher Shumei Okawa, an ideologist of Japanese militarism, was found mentally unfit for trial, while Former Foreign Minister Yosuke Matsuoka and former Chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy General Staff Marshal Admiral Osami Nagano died of natural causes during the trial.

All the capital punishments were carried out on the night of 22-23 December 1948 in the courtyard of Sugamo Prison in Tokyo.

Released in 10 years

In the late 1950s, all those who had been sentenced to prison by the Tokyo Tribunal and survived - former politicians and war criminals alike - had been released and pardoned. Some of them took up key positions in Japan's ruling government and self-defence forces (the country is still banned from having a full-fledged army), Mikhailov noted.

"For example, Mamoru Shigemitsu, Japan's Foreign Minister during the war, who was sentenced to seven years in prison, was released after four years and seven months,” the historian recalled. “After his release, he once again became Minister of Foreign Affairs.”

However, despite all the disagreements between the allies, the Tokyo Tribunal remains relevant to this day.

“The Tokyo and Nuremberg Trials laid the foundations for modern norms and principles of international law,” Alexander Mikhailov pointed out. “The normative legal instruments drawn up at the time are still in force today. They stipulate that the gravest crime is the unleashing and waging of a war of aggression. They completely prohibit the use and development of bacteriological and chemical weapons”.

Commentary

Professor Stanislav Davydov, Doctor of History, Head of the Scientific and Methodological Department of the Victory Museum:

“Tokyo Tribunal judgements and decisions still restrict Japan's sovereignty”

The Tokyo Tribunal, just as the Nuremberg Tribunal, demonstrated the inevitability of punishment for large-scale crimes and inhumane, cannibalistic policies. However, the Tokyo Tribunal had its specific feature: it took place against the backdrop of the outbreak of the Cold War. The Tokyo Tribunal can be regarded as the last "joint work" of the USSR and the Allies in the international arena before the open confrontation between the two world systems unfolded.

Both the Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials were established to punish those responsible for instigating World War II, those who had committed numerous and atrocious crimes. But the Nuremberg Trials preceded the Tokyo Trials and had a great influence on the latter, especially in the field of law enforcement.

The Tribunals had a number of similarities, which can be summarised as follows:

– The purpose was to punish warmongers and criminals and lay the foundations for preventing a repetition of such actions in the future.

– The Tribunals brought together ideologically different countries with different legal systems on a single legal field.

– The Charters of the Tribunals have no substantial differences.

– In legal terms, the Tribunals have fundamentally the same structure.

However, there were some differences:

– At the Tokyo Trial, the US took the lead, being in charge of directing the process.

– At the Tokyo Trial, there was designated one chief prosecutor representing the US instead of four equal prosecutors from four countries.

– Unlike the Tribunal in Europe that focused on crimes against humanity, the Tribunal for the Far East concentrated more on the outbreak and conduct of wars of aggression.

The Tribunal examined the actions of Japanese political and military leaders who planned, prepared, launched and conducted wars of aggression against other countries; grossly flouted and violated international law, treaties and agreements; and committed war crimes and crimes against humanity.

The main tangible outcome of the Tokyo Trial was the demonstration to the Japanese political elite of its new position in the post-war world. At the international level, the Tribunal was designed to show the unity of the Allies in the pursuit of punishing the warmongers but it was not fully successful in doing so.

In many respects, Japan's sovereignty remains limited precisely because of the outcome of this process. At the international level, the Tribunal was one of the last instances where the Allies acted together.

However, one of the key precedents set by the Tribunal was to shift responsibility from the real perpetrators of the war and war crimes attributable to members of the imperial family to their subordinates and to absolve potentially useful war criminals among the academics.

We are grateful to the Victory Museum on Poklonnaya Hill for assistance in preparing the material.

By Daniil Sidorov