Women in concentration camps

From the beginning of 1945, the Allied forces liberated Nazi concentration camps one by one. The peak was in April, when the soldiers of the coalition to defeat Adolph Hitler entered the camps of Dachau, Buchenwald, Ravensbrück and Bergen-Belsen. At the Nuremberg trials, the whole world learned about the atrocities that were happening behind the barbed wire of the camps. The most detailed evidence was given by the Frenchwoman Marie-Claude Vaillant-Couturier, a former prisoner of Auschwitz and Ravensbrück. Those who survived in these camps owe their salvation to the Red Army: on 27 January 1945 it liberated Auschwitz, and during the period from 30 April to 3 May 1945, all the camps of the Ravensbrück complex were liberated as well.

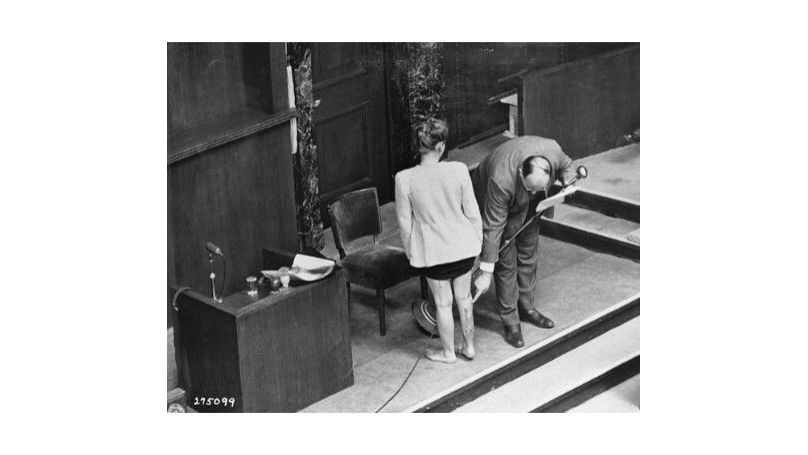

Marie Claude Vaillant-Couturier was born in 1912 and lived in Paris. She was a photojournalist. After the war, she became a leader of the women's democratic movement, a member of the Constituent Assembly, and was awarded an order of the Legion of Honor.

On 9 February 1942 she was arrested by the Vichy police and handed over to the Gestapo. She was kept in various prisons in France for a year, then in January 1943 she was sent to Auschwitz with a group of French women, and then, in May 1944, to Ravensbrück.

The excerpts from the interrogation of the witness on 28 January 1946 were used in the article.

Auschwitz

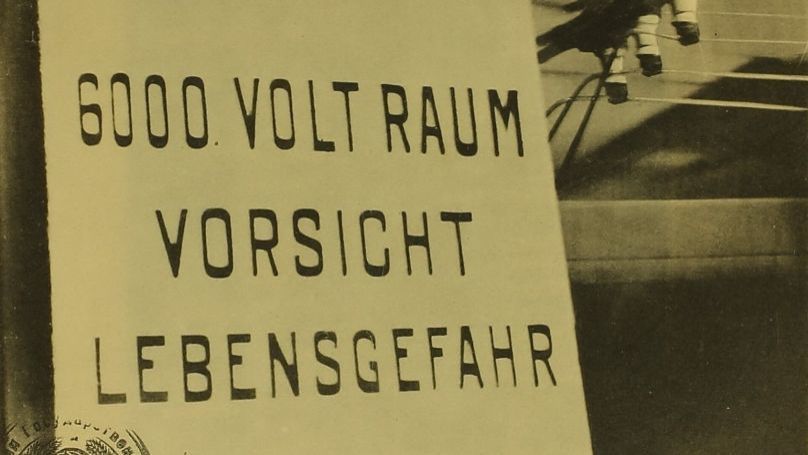

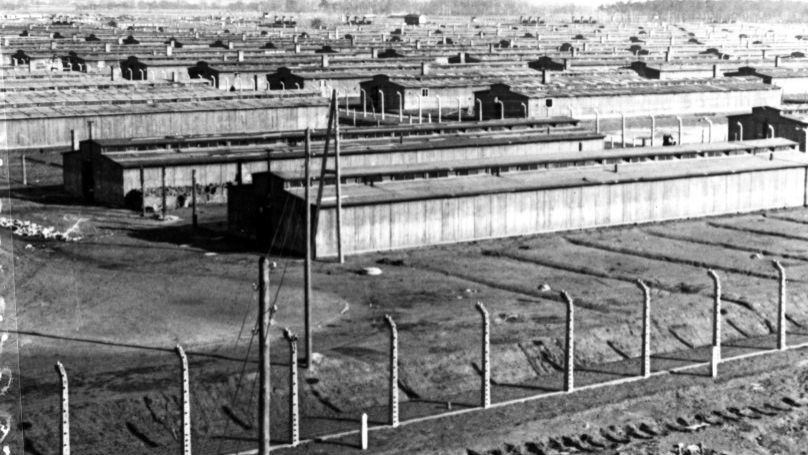

“The largest Nazi death camp, located 60 km west of Krakow in occupied Poland. The first prisoners were taken to the camp in May 1940. It is impossible to determine the total number of prisoners and victims of Auschwitz. According to historians, during the existence of the camp, between 1.1 million and 1.6 million people were exterminated there.

“One never comes back from there”

At the end of my interrogation, they wanted me to sign a statement which was not consistent with what I had said. I refused to sign it. The officer who had questioned me threatened me, and when I told him that I was not afraid of death nor of being shot, he said, "But we have at our disposal means for killing that are far worse than merely shooting." And the interpreter said to me, "You do not know what you have just done. You are going to leave for a concentration camp in Germany. One never comes back from there.”

The first day

We arrived at Auschwitz at dawn (...) and taken to the Birkenau Camp, a section of the Auschwitz Camp. It is situated in the middle of a great plain, which was frozen in the month of January. During this part of the journey we had to drag our luggage. As we passed through the door we knew only too well how slender our chances were that we would come out again, for we had already met columns of living skeletons going to work; and as we entered we sang "The Marseillaise" to keep up our courage. (...) And toward the evening an orchestra came in. It was snowing and we wondered why they were playing music. We then saw that the camp foremen were returning to the camp. Each foreman was followed by men who were carrying the dead.

“They were not even counted”

The system had been improved. Instead of making the selection at the place where they arrived, a side line now took the train practically right up to the gas chamber; (...)we saw the unsealing of the cars and the soldiers letting men, women, and children out of them. (...) All these people were unaware of the fate awaiting them. (...). To render their welcome more pleasant at this time-June-July 1944-an orchestra composed of internees, all young and pretty girls dressed in little white blouses and navy blue skirts, played during the selection, at the arrival of the trains, gay tunes such as "The Merry Widow," the "Barcarolle" from "The Tales of Hoffman," and so forth. (…)Those selected for the gas chamber, that is, the old people, mothers, and children, were escorted to a red-brick building. (...)

Later on, at the time of the large convoys from Hungary, they had no more time left to play-act or to pretend;

M. DUBOST: These were not given an identification number?

MM. VAILLANT-COUTURIER: No.

M. DUBOST: They were not tattooed?

MM. VAILLANT-COUTURIER: No. They were not even counted.

“It did not matter who were to be destroyed - children, old people or soldiers, age and the victims` condition were not taken into account; it was not about terms and categories, it was about characteristics and qualities. A Jewish or Gypsy child was just a Jew or a Gypsy, not a child; they simply destroyed Jews, Gypsies, Russians and Poles; they didn’t destroy old people or women, but erased dark spots from the perfect image of the everlasting, true Reich."

Boris Yakemenko "The world of concentration camps"

“We await your arrival”

When we left Romainville, the Jewish women who were there at the same time as ourselves were left behind. They were sent to Drancy and subsequently arrived at Auschwitz, where we found them again three weeks later, three weeks after our arrival. Of the original 1,200 only 125 actually came to the camp; the others were immediately sent to the gas chambers. Of these 125 not one was left alive at the end of one month. (...)

I knew a little Jewish girl from France (…) She was called "little Marie" and she was the only one, the sole survivor of a family of nine. Her mother and her seven brothers and sisters had been gassed on arrival. When I met her, she was employed undressing the babies before they were taken into the gas chamber. (...)

As for the Jewish women from Salonika, I remember that on their arrival, they were given picture postcards, bearing the post office address of "Waldsee," a place which did not exist; and a printed text to be sent to their families, stating, "We are doing very well here; we have work and we are well treated. We await your arrival." I myself saw the cards (...)

I myself know that the following affair occurred in Greece. I do not know whether it happened in any other country, but in any case it did occur in Greece (as well as in Czechoslovakia) that whole families went to the recruiting office at Salonika in order to rejoin their families. I remember one professor of literature from Salonika, who, to his horror, saw his own father arrive.(...)

Likewise, on the other side, there was the so-called family camp. These were Jews from the Ghetto of Theresienstadt, who had been brought there and, unlike ourselves, they had been neither tattooed nor shaved. Their clothes were not taken from them and they did not have to work. They lived like this for 6 months and at the end of 6 months the entire family camp, amounting to some 6,000 or 7,000 Jews, was gassed.

Everyday life

At 3:30 in the morning the shouting of the guards woke us up, and with cudgel blows we were driven from our bunks to go to roll call. Nothing in the world could release us from going to the roll call; even those who were dying had to be dragged there. We had to stand there in rows of five until dawn, that is, 7 or 8 o'clock in the morning in winter; and when there was a fog, sometimes until noon. Then the commandos would start on their way to work.

(…)

In Auschwitz, obviously, extermination was the sole aim and object. Nobody was at all interested in the output. We were beaten for no reason whatsoever. It was sufficient to stand from morning till evening but whether we carried one brick or 10 was of no importance at all. We were quite aware that the human element was employed as slave labour in order to kill us. (...)

The German women had cudgels and they beat us more or less at random. We had a comrade, Germaine Renaud, a school teacher from Azay-le-Rideau in France, who had her skull broken before my eyes from a blow with a cudgel during the roll call.

(...)

During the work, the SS men and women who stood guard over us would beat us with cudgels and set their dogs on us. Many of our friends had their legs torn by the dogs. I even saw a woman torn to pieces and die under my very eyes when Tauber, a member of the SS, encouraged his dog to attack her and grinned at the sight. (...)

At the beginning, there were only SS men, but from the spring of 1944 the young SS men in many companies were replaced by older men of the Wehrmacht both at Auschwitz and also at Ravensbruck. We were guarded by soldiers of the Wehrmacht as from 1944.

“The entire structure of a prisoner's life from top to bottom reflected the symbolic system of a totalitarian and total state and placed prisoners at the lowest tiers of the system or even under its surface. At the same time, the more people got into the camps and the harsher the treatment was - the more absolute the totality was itself.”

Boris Yakemenko "The world of concentration camps"

Block 25

This Block 25, which was the anteroom of the gas chamber, if one may say so, is well known to me because at that time we had been transferred to Block 26 and our windows opened on the yard of Number 25. One saw stacks of corpses piled up in the courtyard, and from time to time a hand or a head would stir among the bodies, trying to free itself. It was a dying woman attempting to get free and live. The rate of mortality in that block was even more terrible than elsewhere because, having been condemned to death, they received food or drink only if there was something left in the cans in the kitchen; which means that very often they went for several days without a drop of water.

One of our companions, Annette Epaux, a fine young woman of 30, passing the block one day, was overcome with pity for those women who moaned from morning till night in all languages, "Drink. Drink. Water!" She came back to our block to get a little herbal tea, but as she was passing it through the bars of the window she was seen by the Aufseherin, who took her by the neck and threw her into Block 25. All my life I will remember Annette Epaux. Two days later I saw her on the truck which was taking the internees to the gas chamber. She had her arms -around another French woman, old Line Porcher, and when the truck started moving she cried, "Think of my little boy if you ever get back to France." Then they started singing "The Marseillaise".

Evil doctors

I have seen in the Revier, because I was employed at the Revier, the queue of Jewish girls from Salonika who stood waiting in front of the X-ray room for sterilisation. I also know that they performed castration operations in the men's camp.

Concerning the experiments performed on women I am well informed, because my friend, Doctor Hade Hautval of Montbeliard, who has returned to France, worked for several months in that block nursing the patients; but she always refused to participate in those experiments. They sterilised women either by injections or by operation or with rays. I saw and knew several women who had been sterilised. There was a very high mortality rate among those operated upon. (...)

The sterilisation-they did not conceal it. They said that they were trying to find the best method for sterilising so as to replace the native population in the occupied countries by Germans after one generation, once they had made use of the inhabitants as slaves to work for them. (...)

There was also, in the spring of 1944, a special block for twins. It was during the time when large convoys of Hungarian Jews, about 700,000, arrived. Dr. Mengele, who was carrying out the experiments, kept back from each convoy twin children and twins in general, regardless of their age, so long as both were present. So we had both babies and adults on the floor at that block. Apart from blood tests and measuring, I do not know what was done to them.

Mothers and babies

If pregnant Jewish women arrived during the first months of their pregnancy, they were forced to get abortions. If their pregnancy was near its end, after confinement, the babies were drowned in a bucket of water. (...) The woman who was in charge of that task was a German midwife, who was imprisoned for having performed illegal operations. After a while, another doctor arrived and for two months they did not kill the Jewish babies. But one day an order came from Berlin saying that again they had to be done away with. Then the mothers and their babies were called to the infirmary. They were put in a lorry and taken away to the gas chamber.(…) In principle, non-Jewish women were allowed to have their babies, and the babies were not taken away from them; but conditions in the camp being so horrible, the babies rarely lived for more than 4 or 5 weeks.

There was one block where the Polish and Russian mothers were. One day the Russian mothers, having been accused of making too much noise, had to stand for roll call all day long in front of the block, naked, with their babies in their arms.

Pits and furnaces

At Auschwitz there were eight crematories but, starting in 1944, these proved insufficient. The SS had large pits dug by the internees, where they put branches, sprinkled with gasoline, which they set on fire. Then they threw the corpses into the pits. From our block we could see after about three-quarters of an hour or an hour after the arrival of a convoy, large flames coming from the crematory, and the sky was lit up by the burning pits. One night we were awakened by terrifying cries. We discovered, the following day, from the men working in the Sonderkommando - the "Gas Kommando" - that on a preceding day, the gas supply having run out, they had thrown the children into the furnaces alive.

***

We could not believe our eyes when we left Auschwitz and our hearts were sore when we saw the small group of 49 women; all that was left of the 230 who had entered the camp 18 months earlier. But to us it seemed that we were leaving hell itself, and for the first time hopes of survival, of seeing the world again, were vouchsafed to us.

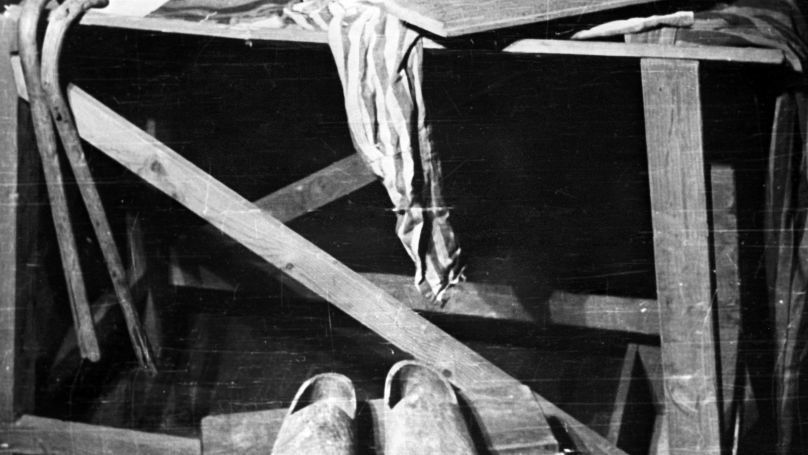

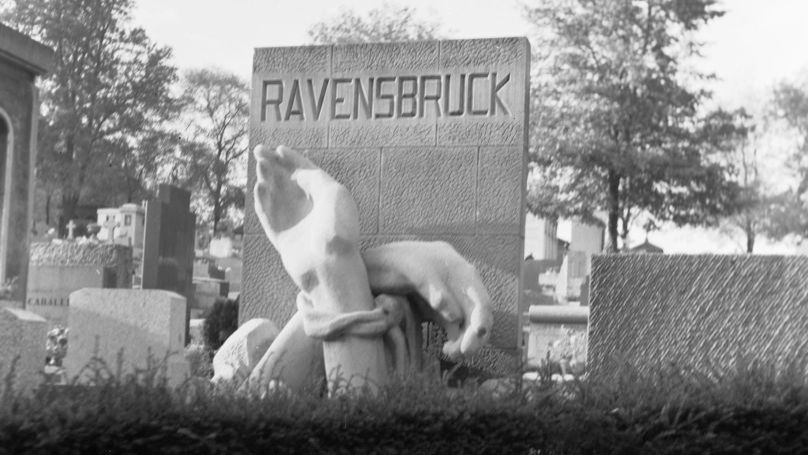

Ravensbrück

The camp was opened in May 1939, 100 km north of Berlin. Primarily, women were kept there. More than 50 thousand people of the 132 thousand prisoners who had been held in Ravensbrück died.

Slavery

In Ravensbruck. there was the Siemens factory, where telephone equipment was manufactured as well as wireless sets for aircraft. Then there were workshops in the camp for camouflage material and uniforms and for various utensils used by soldiers. (...)

At Ravensbruck, the output was of great importance. It was a clearing camp. When the convoys arrived at Ravensbruck, they were rapidly dispatched either to the munition or to the powder factories, either to work at the air fields or, later on, to dig trenches.

(...)

The manufacturers or their foremen or else their representatives were coming themselves to choose their workers, accompanied by SS men; the effect was that of a slave market. They felt the muscles, examined the faces to see if the person looked healthy, and then made their choice. Finally, they made them walk naked past the doctor and he eventually decided if a woman was fit or not to leave for work in the factories. Later on, the doctor's visit became a mere formality as they ended by employing anybody who came along. The work was exhausting, principally because of lack of food and sleep, since in addition to 12 solid hours of work one had to attend roll call in the morning and in the evening. (...)

Work was carried on at a furious pace; the internees could not even take time off to go the lavatory. Both day and night they were terribly beaten, both by the SS women and men, if a needle broke due to the poor quality of the thread, if the machine stopped, or if these ‘ladies’ and ‘gentlemen' did not like their looks. Towards the end of the night, one could see that the workers were so exhausted that every movement was an effort for them. (...) When the standard amount of work was not reached, the foreman, Binder, rushed up and beat up, with all his might, one woman after another all along the line, with the result that the last in the row waited their turn petrified with terror.

Experimental "rabbits"

With us in that block were Polish women; Some were called "rabbits" because they had been used as experimental guinea pigs. They selected from the convoys girls with very straight legs who were in very good health, and they submitted them to various operations. Some of the girls had parts of the bone removed from their legs, others received injections; but what was injected, I do not know. The mortality rate was very high among the women operated upon. So when they came to fetch the others to operate on them they refused to go to the Revier. They were forcibly dragged to the dark cells where the professor, who had arrived from Berlin, operated in his uniform, without taking any aseptic precautions, without wearing a surgical gown, and without washing his hands. There are some survivors among these "rabbits." They still endure much suffering. They suffer periodically from pus discharges.

“Unprecedented violence was a consequence of the extreme pressure of the state on society; through violence, the state presented itself to society. As a result of this pressure, a fundamentally new category of people should have been created (like graphite turns into diamond under extreme pressure), which would ensure the irreversibility of the process. It is not a coincidence that the creation of a "new man", the search for new physical capabilities of a human being, which led to human experimentation in the concentration camps, permeates the entire ideology of the Third Reich."

Boris Yakemenko "The world of concentration camps"

“They were therefore rotting in this filth”

“There was no longer any room left in the blocks, and the prisoners already slept four in a bed, so there was raised, in the middle of the camp, a large tent. Straw was spread in the tent, and the Hungarian women were brought to this tent. Their condition was frightful. There were a great many cases of frozen feet because they had been evacuated from Budapest and had walked a good part of the way in the snow. A great many of them had died en route. Those who arrived at Auschwitz were led to this tent and there an enormous number of them died. Every day a squad came to remove the corpses in the tent. One day therefore, as I was saying, I passed the tent while it was being cleaned, and I saw a pile of smoking manure in front of it. I suddenly realised that this manure was human excrement since the unfortunate women no longer had the strength to drag themselves to the lavatories. They were therefore rotting in this filth. (…)

It was in the winter of 1944, about November or December, I believe, though I cannot say for certain which month it was. It is so difficult to give a precise date in the concentration camps since one day of torture is followed by another day of similar torment and the prevailing monotony makes it very hard to keep track of time.

Liberation

When the Germans went away they left 2,000 sick women and a certain number of volunteers, myself included, to take care of them. They left us without water and without light. Fortunately, the Russians arrived on the following day. We therefore were able to go to the men's camp and there we found a perfectly indescribable sight. They had been there for five days without water. There were 800 serious cases, and three doctors and seven nurses, who were unable to separate the dead from the sick. Thanks to the Red Army, we were able to take these sick persons over into clean blocks and to give them food and care; but unfortunately I can give the figures only for the French. There were 400 of them when we came to the camp and only 150 were able to return to France.

***

It is difficult to convey an exact idea of the concentration camps to anybody, unless one has been in the camp oneself, since one can only quote examples of horror; but it is quite impossible to convey any impression of that deadly monotony. If asked what was the worst of all, it is impossible to answer, since everything was atrocious. It is atrocious to die of hunger, to die of thirst, to be ill, to see all one's companions dying around one and being unable to help them. It is atrocious to think of one's children, of one's country which one will never see again, and there were times when we asked whether our life was not a living nightmare, so unreal did this life appear in all its horror.

For months, for years we had one wish only: The wish that some of us would escape alive, in order to tell the world what the Nazi convict prisons were like everywhere, at Auschwitz as at Ravensbruck. And the comrades from the other camps told the same tale; there was the systematic and implacable urge to use human beings as slaves and to kill them when they could work no more.”

Sources:

Sergei Miroshnichenko, “Transcript of the Nuremberg Trials”, Volume VIII

Boris Yakemenko "The world of concentration camps of Nazi Germany. Main features of the phenomenon of unknown”. Russian journal of linguistics of RUDN University. Series: General history. 2020. Volume 12. № 1.