By Andrei Sukhanov

One and a half million of them came. In Paris, 300,000. Among them were those who rushed, driven by hatred, to the banners of Hitler. But there were others, to whom the very possibility of doing such a thing was inconceivable. They were driven by various motives, but not by self-interest. Four famous representatives of the "Russian character", one of whom even gave the name to the French Resistance movement.

Loyalty

At home, Anton Ivanovich Denikin was as simple as a soldier should be. The couple were on a first-name basis; his wife even called him "Ivanich". He twisted French words in the Russian manner, called the aperitif "operative", the game "bilboquet" - "gorodki". He named a stray kitten Vaska; it was resting on a desk, basking under a lamp on manuscripts. The general tended the garden himself and swept the yard. Sometimes, when his wife and daughter weren't around, he would say some coarse Russian words.

Anton Ivanovich could not understand how the French leadership had lost the war in such a short time when they had one of the best armies in the world. He had lost battles, and even war - but he had fought to the end, his soldiers clinging to every inch of ground.

To lose a war out of cowardice, without really fighting back, seemed to him a disgrace. Soon new forces were in power - the French were ruled by the Germans, although formally the unoccupied area was "ruled" by Marshal Pétain.

Anton Ivanovich did not believe it at first when his wife was arrested. On 15 June 1941, some Gestapo or SS officers arrived, he thought for sure they were after him. It turned out that they were after her. They released her soon enough but put her under surveillance. She refused to leave the ward: there were many Russians in prison and Germans did not have interpreters yet, she could not leave her compatriots without any help.

Once a week, a German officer came to the house and rummaged through the papers. Soon all the books ended up on the ban list. These Germans could not read Russian. It became obvious that the list had been compiled and passed on to them by Russian "readers".

Soon Ataman Andrei Shkuro and Generals Pyotr and Semyon Krasnov joined the Germans.

And they did not just defect - they swore an oath, put on epaulettes! Denikin was not surprised. The general was 70 years old, he was not naive, and learned the value of these figures back in Russia. In winter, he was offered to move to Germany, to work in archives; he was promised money. The only thing he could answer was, "I need nothing. I will not go anywhere until the end of the war". And the "inviting people" understood exactly what end of the war he was referring to.

Meanwhile, he, his wife, and his daughter had nothing to eat. The last 10 kilos of potatoes were frozen, the oil from the remaining can of sardines was saved to dress the lentils. Vaska, who always licked those tins, was very unhappy... His wife, Ksenia Vasilievna, wrote on a picture of the two of them in the garden, "How skinny we all have become".

And then... Prince Dmitry Alekseyevich Shakhovskoy, an Orthodox priest, a hierarch! What did he write in his own name, in the newspaper?

"The professional, military, iron-precise hand of the German Army, tried in the most important battles, was needed. It is now charged with knocking down the red stars from the walls of the Russian Kremlin, it will knock them down if the Russian people do not knock them down themselves… This army, which was victorious throughout Europe, is now strong not only by the strength of its armaments and principles but also by that obedience to a higher call, which Providence has placed upon it beyond all political and economic calculation. Above all human beings, the sword of the Lord is at work".

But the most disgusting thing was still ahead. One day, the local German commandant came to his house, and with him a Soviet general. I mean, not a Soviet one anymore. The SS General Andrey Vlasov.

The conversation was short. Various sources confirm these words: "I am a Russian officer and have never worn a foreign uniform. And you dared to come to me in the uniform which was put on you by the enemies of the Russian people. We have nothing to talk about".

If they had a moment to talk in private, I think Anton Ivanovich said nothing to him at all. Doesn't deserve the honour.

In 1943, he managed to secretly buy and smuggle a carload of very high quality "white" sulfanilamide with money collected by emigrants. Stalin was extremely surprised and puzzled and ordered to take the medicine, but where it came from - to be kept a secret. Except history doesn't have everlasting secrets.

Anton Denikin hated Bolshevism and the Bolsheviks. But he loved his country until his death. He could not become an active participant in the resistance - he was too exposed, and, most importantly, he was already very ill.

But he always told the captive officers and soldiers from the mysterious Soviet Union that the Germans could not win this war - they did not have the guts. About soldiers made from former prisoners of war, he wrote: "It is so ridiculous, so strange to see these Russian men in German uniforms, and, to put it bluntly, how can it be? You see, you simply can't serve Russia's enemy... You must not!"

And about those who made the choice themselves - as follows:

"In such matters, the driving force in deals of moral compromise is mostly power and self-interest, sometimes, however, despair. Despair about the fate of Russia. At the same time, to justify their anti-national work and ties, most often an explanation is put forward; it's only for excitement, and then you can turn the bayonets... Such statements were made openly by two bodies that claim to lead the Russian émigrés... Excuse me, but this is too naïve. It is naïve to enter into business relations with a partner and warn that you will deceive him, and naïve to count on his unconditional trust. You will not turn your bayonets, for having used you as agitators, translators, jailers, perhaps even as a fighting force - imprisoned in the clutches of his machine guns - this partner will in due course neutralise you, disarm you, if not exterminate you in concentration camps. And you will shed the blood, not of the Chekists, but simply the blood of Russians - your own and your own people in vain, not for the liberation of Russia, but to further enslave it".

One would guess that some other words were found for the misguided. In private encounters.

Anton Ivanovich Denikin, 1872 -1947

Faith

Father Dimitri, a rector of the house church of the Protection of the Blessed Virgin at the Russian hostel Rue de Lourmel, had no illusions about his church career. There are some clergymen who pray to God and never forget themselves. Well, he had.

In 1942, neither the German commandant's office nor the Gestapo, but the Orthodox diocesan office demanded a register of the newly baptised from 1940. Those who requested it knew perfectly well that Father Dmitry had issued baptismal certificates to many Jews and that this had saved them from death, without requiring them to renounce their Jewish faith. How convenient to fight for the purity of the faith, if it would also be rewarded with indulgences from the dangerous Nazi authorities!

And he kept saying: "...I will allow myself to reply that all those who - regardless of external motives - have been baptised by me are thus my spiritual children and are under my direct guardianship. Your request could only be due to external pressure, and was dictated to you for reasons of a police nature. For this reason, I must refuse to give the requested information".

The case of Father Dmitry was handled by an SS officer, Hoffmann. Not the famous Otto Hoffmann, head of the SS Race and Settlement Main Office. An unknown, nameless Hoffmann, a grey mouse in a black uniform. The most convenient last name! Like Smith in England, Ivanov in Russia, Dubois in France... Take off your uniform and you are gone. But Hoffman was about to become famous. During a search, he found a letter from a Jewish woman asking for a certificate of baptism. Hoffmann summoned Father Dimitry to the Gestapo.

The interrogation began. No one would have known what had happened if it had not been for Hoffmann himself. He decided to tell the story of the "stubborn priest" in the very hostel on Rue de Lourmel to intimidate his listeners. Hoffmann offered the priest his freedom on the condition that he would not give any more baptism papers to Jews. In response, Fr. Dimitry pointed to a crucifix and said: "Do you know this Jew?"

"Your priest has brought his own downfall. He kept saying that if he was released, he would do the same thing as before", the SS man said frankly.

Father Dmitry was abused in the camp more often than the others. He said: "If I had not been a priest, if I had not done this, I would have been a most unhappy man... My God-given path has saved me, and I only grieve and feel sad that I do so little. Here we are imprisoned, as if there is nothing to do, and how much I have not done, because I am slothful..."

In Paris, his compatriots did all they could to save him. They turned to a German pastor to persuade the Nazi authorities to help free him. However, the pastor demanded first to notify the prisoner that he had to promise to do nothing but services and prayers.

"We still bear responsibility and are equally not guilty of anything", Father Dimitry replied.

In the concentration camp, he stripped himself of his F badge - he was a French citizen and was treated more leniently - and replaced it with a Soviet POW's one. In December 1943, he was transferred to the Dora camp, to the underground factories to produce V-2s. There he fell seriously ill. The prisoners tried to relieve him of his hard labour, believing him to be old - and were astonished when he told them he was only 39 years old. The warden of the hospital barracks where Father Dimitry was delivered with pleurisy said that before he died, he asked for his hand to be raised and to be blessed with a cross.

Father Dimitry was a member of the Resistance, an associate of the famous Mother Maria.

He died on 9 February 1944. According to the recollections of Buchenwald prisoner Fedor Pyanov, "He died of pneumonia on the dirty floor, in a corner of the so-called 'reception ward' of the camp, where there was no medicine, no care, and no beds. In the evening or night, he died and was probably taken with the other dead men to the crematorium at the Buchenwald camp in the morning. At the time, the deceased at the Dora camp were burnt in Buchenwald".

He did not leave behind any written works, only a few letters. He did not make a career in the church hierarchy, nor did he aspire to one. In 2004, Father Dmitry, known worldwide as Dmitry Andreevich Klepinine, was canonised. Cardinal Aron Jean-Marie Lustiger, archbishop of Paris, urged the faithful to pray for the Orthodox martyr Dimitry just as they do for the saints and patrons of France. The State of Israel has named him "Righteous Among the Nations" and his name is inscribed in Yad Vashem, the national memorial to the victims of the Holocaust.

No one has ever seen the register of those baptised in 1940. Never.

Dimitry Andreevich Klepinine, 1904-1944

Wisdom

"The origins of morality: the experience of remorse, but isn't that ultimately love? Think about it. The emergence of language. Mother and child. Perhaps".

"In the end, language is not only a way of expression but also a way of shaping thought. In other words: thought is a way of expressing the spirit of the language".

"The superhuman world is a machine for making gods, and so on and so forth. But Nietzsche's excitement is stronger, more immediate; Bergson is more scientific. It is difficult to predict what impact 'Zarathustra' will have; what is certain is that this book will have a very strong influence on the National Socialist movement in Germany (I leave the question of the authenticity of Nietzscheanism open)".

The author of these words was an excellent linguist and ethnographer, an athlete and a writer of poetry. And he worked in Paris at the Musée de l'Homme.

– "It is easy to talk about philosophy, language and conscience in office-library seclusion when there is war all around", a casual reader would say. He is not entirely wrong: there was solitude.

"Solitary confinement is where a man shows his full worth. Wisdom in comparison to intelligence is like kindness in contrast to politeness. Happiness is gained only by suffering. If not happiness, then serenity".

A man wrote a diary such as this in a solitary cell.

"Prison gives you nothing, but it acts on me like a developer on a film. It's something like a darkroom.

Meaningless pain humiliates, but suffering empowers, transforms. Is it possible to turn one into the other?"

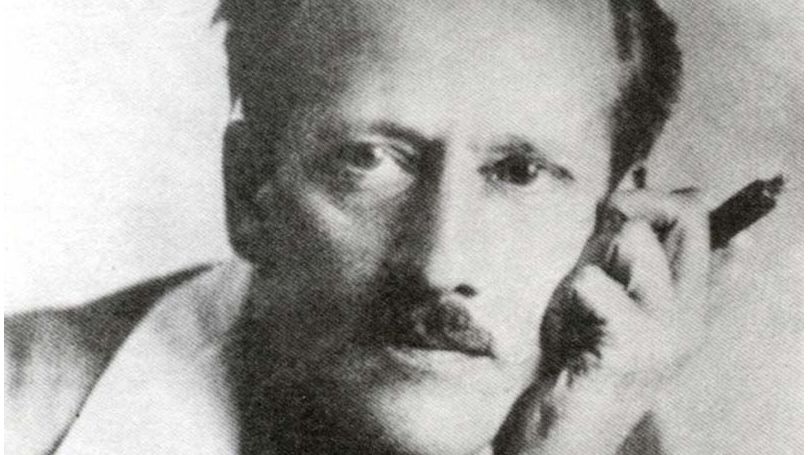

In 1939, he was conscripted into the French Army and was later captured. But in early July 1940, he escaped, returned to occupied Paris and immediately set up one of the first Resistance groups. In March 1941, he was arrested. Together with his Russian colleague, Anatole Lewitsky, he set up a resistance movement, which was called the "Groupe du Musée de l'Homme" (French for "Group of the Museum of Man"). This name was coined by the Gestapo. The group's founders called it "Comité National de Salut Public" (National Committee for Public Safety). It had 30 members.

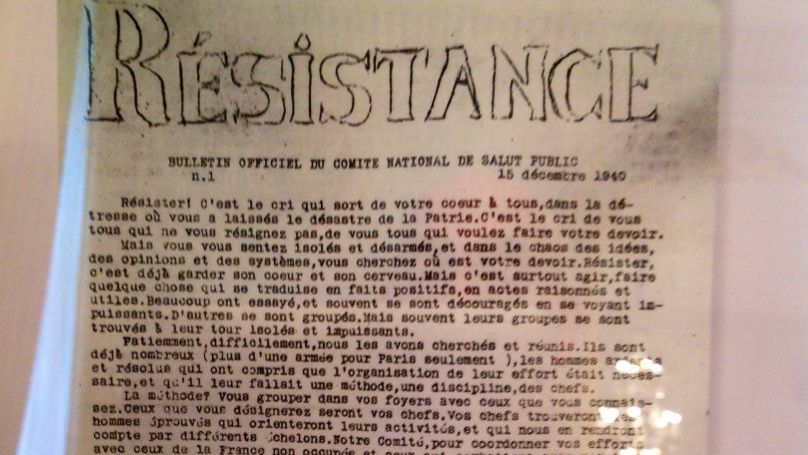

They quickly found links with the Gaullist underground groups, printed several hundred copies of the radio appeal "33 Tips to the Occupied", the leaflet "De Gaulle, We Stand with You!", a denunciatory open letter to collaborator Philippe Pétain, and distributed them by putting them in letterboxes and sticking them on bus walls. On 15 December, they published the first issue of the Resistance newspaper, spread on tiny pieces of paper printed on both sides.

And the name of the newspaper became the name of the entire patriotic anti-Nazi movement in France and across Europe, and it was named by a Russian scientist, Boris Vildé.

His leading article in this newspaper was broadcast by French Gaullist Radio from London. Three issues came out under his editorship, the fourth was edited by the journalist Pierre Brossolette. Vildé made a propaganda trip through the south of France, the Vichy Zone: Marseilles, Lyon, Toulouse... He could have stayed there, but he had to publish the next issue urgently. However, on 26 March 1941, he was arrested.

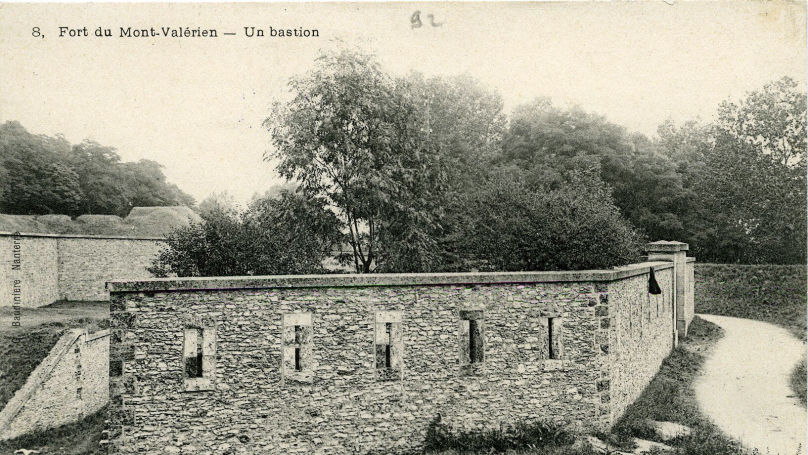

On 23 February 1942, seven anti-fascists were shot at Fort Mont-Valérien. The Germans still believed in victory, that is why the execution was staged with cheap romantic pathos. 12 soldiers, a chaplain, and judges. There was not enough room along the wall, so Boris Vildé and Anatole Lewitsky volunteered to die in second place, supporting their exhausted comrades in the fight. They refused to be blindfolded and sang La Marseillaise before dying.

His wife cherished his last letter as a relic.

"My beloved, dear Irene, forgive me for deceiving you: when I returned to give you one more kiss, I already knew it would be today. To be honest, I'm proud of my deception: you made sure I wasn't frightened and smiled as usual. I am facing life with a smile, like a new adventure, with some regret, but without remorse or fear".

Four weeks before his death, he wrote this four-line poem:

Comme toujours impassible

Et courageux (inutilement)

Je servirai decible

Aux douze fusils allemands.

As unflappable as ever

And brave (perhaps in vain)

I shall serve to be a target –

To the devil’s dozen shooting pain

(Russian translation by A. Sukhanov, English translation by E. Vorobiev)

And one last line from his diary:

"To be a human being before being a German, a soldier, a judge, a man, a father, a Catholic, an artist. This seems so unattainable these days (and always). For a long time, I have been striving for it, but I have not reached even halfway. Anyway, I have learned simplicity, which is a lot. If only I had the talent... But that too is a thing of lesser importance.

Sometimes, I manage to completely detach myself, free myself from everything that makes up my life, everything except Irene. I can't detach myself from her. This is the true measure of my love, the only thing that (at times) still binds me with being. And that is a miracle".

Boris Vladimirovich Vildé, 1908-1942

Secrecy

As emigrants read a novel by an unknown new author, they had no idea they were passing the very bridges under which he slept during the day. For a while, he lived in poverty. In his own words, during his first five years in Paris, he explored every little shop where he could get a night's lodging. He washed steam locomotives in winter, was an assembly line worker at the Renault factory, and somehow managed to study at the Sorbonne and write.

Later, he became a taxi driver, and when the public read the crime chronicle - they had no idea that the novel, once re-read by everyone, came from the reporter's pen, and new novels were forthcoming. Yet, still nothing is known about the writer's private life, only a few letters from unknown women and a rather envious testimony of an acquaintance: "... of small stature, with traces of Asian pox on his ugly face, broad-shouldered, short-necked, like a hornless buffalo, he still had success with the ladies".

Other acquaintances confirm that he did not "still have" success, but very much a serious and constant one - but that's about it. By the way, no evidence of the personal lives of his acquaintances and pals could be found in the writer's own books either. His characters in the books seem to be completely fictional, having no prototypes in reality.

For a researcher, he is an extremely uncomfortable person. For example, it is known that he married Faina Dmitrievna Gavrisheva, née Lamzaki, in 1936...or 1937. They registered their formal marriage only in 1951. And in 1940, he received a pass in the province of Dordogne to return to occupied Paris.

"Pass issued to Mr Georges Gazdanov and his accompanying family of two, his aunt Gavrichef, née Lamzaki, to travel to Paris, where he resides at 69 Rue Brancion. Tivier, 27 September 1940".

In other words, when everyone was eager to leave occupied Paris, he returned there. For some reason, the wife is referred to as "aunt". The wife's niece Tania is not mentioned at all...

There is a postcard to his friends, Mikhail and Tatiana Osorgin, dated August 1942. For over two years, they had not heard from him at all! For some reason...

Paris 24/VIII 42

Mes chers amis, excusez-moi de n’avoir pas ecrit jusqu’a present. J’etais bien au courant de se que vous faisiez par l’intermediaire de madame Emilie et de Michel. Je n’ecrivais pas, car on peut dire si peu de choses dans une carte et cela me de courageait. Mais je tiens quand meûme a rappeler timidement que j’existe toujours et que tant que j’existe, je garderai les me(û)mes sentiments envers vous. Je vous souhaite bien des choses et de preference les meuilleurs que puissent vous faire plaisir.

Je vis paisiblement et j’ecris des choses insignifiantes. J’ai l’occasion de parler souvent de vous chaque fois que je vois nos amis communs, il est vrai qu’il en reste de moins en moins. Je serais heureux si cette petite carte revive en vous le souvenir de votre toujours devoue

Gasdanoff.

"My dear friends, forgive me for not writing to you until now. I have been privy to your affairs by Madame Emily and Michel. I have not written, for so little can be written in a postcard, and it just infuriates me. But I want without further ado to remind you that I am still alive, and as long as I am, I retain the same feelings for you. I wish you all the best that can make you happy. I live peacefully and write some little things. Whenever possible, I talk about you every time I see our mutual friends, though there are fewer and fewer of them left. I would be happy if this postcard would remind you of the eternally devoted.

Gazdanov.

A Russian writes to Russians... in French? Well, yes, under the occupation regime, letters are opened, and this is even a postcard. But here is the Osorgins' reply to a negligent friend who could not find the time to write them a postcard in two years. A friend, who deserves a bit of scolding and at least a reproach - if you write trifles, why not just scribble a letter, a couple of lines: "alive, I love you, I remember you. Happy new year, happy birthday..."

To Gazdanov

69, rue Brancion Paris 15 e

5.9.42

Dear Georgii Ivanovich,

We have received your card out of the blue. Thank you for writing, every line is worth its weight in gold for us. Please, do not think that we have not thought of you. ...just recently we even made a whole list of all our loved ones and were figuring out where everyone was and what threats they might face.

And another thing:

"Please, write to us and let us know if you need our village help with the fruits of the earth. We shall be glad to send you what we can. Although you have written many times to the Shemams [the family of their mutual friend Georgii Feofilovich Shemetillo] that you are living fine, let us have doubts about that".

It is also known that the writer Gaito (Georgii Ivanovich) Gazdanov indeed wrote almost nothing during the war years.

And here is another fact, confirmed by a document. In February 1947, Igor Krivoshein, chairman of the Russian branch of the Union of Volunteers, Partisans, and Resistance Movement in France gave Gaito Gazdanov a certificate stating that from October 1943, he was a member of the "Russian Patriot" group, and from February 1944, he was the editor of a newspaper with the same name. That is all.

However, a variety of Gazdanov's biographies suggest that he was a member of the Resistance, helped hide the Jews and escaped Soviet soldiers, many of whom he sheltered in his own tiny flat, where they slept on a sofa in the corridor, and joined a partisan brigade set up by Soviet prisoners. Well, let's say – about the prisoners, yes, that could have happened in 1943. But it was already too late to hide the Jews in 1943! And the most important thing - could a man of such willpower, Russian culture, and Caucasian pride would do nothing from 1940 to October 1943? Did he join the evidently victorious side? No, it is not possible. It simply cannot be.

Or here is another fact: in 1935, Gazdanov asked Alexei Maximovich Gorky to facilitate his return to the USSR. However, he was not allowed to return, and certainly, it was not Gorky. And in 1939, Gazdanov signed a declaration of allegiance to the French Republic on 1 September. No one coerced him, agitated him, or even asked him to do so. Even France itself declared war on Germany a day later! What was the point then?

In 1941, a wave of arrests swept through Resistance units. Many people were executed, sent to Nazi concentration camps. But the Resistance persisted, and not merely as a declaration, but as an active and combat one, conducting military reconnaissance. And such work requires absolute secrecy. It could be entrusted only to those absolutely reliable and able to keep a secret, unpretentious in everyday life, accustomed to hardship. And such work would certainly require a man, whose love affairs and romances have never been proved or witnessed with any certainty. Scrupulous in matters of honour down to insignificant (for others) trifles. Accustomed to washing steam locomotives at the Marseilles depot, who knew Paris well down to the most squalid corners, who knew tramps and criminals, who worked as a reporter for crime news, who drove a taxi at night...

But what Russian writer Gaito Gazdanov was up to during those years, we may never know. However, time goes by. And it is likely that, after some time has passed, the now secret archives will be opened and we will find out... or rather, we will just get some proof of what we have already guessed.

"If you have strength, if you have resilience, if you are able to resist misery and adversity, if you don't lose hope that things can get better, remember that others don't have that strength or that ability to resist. And you can help them. Do you understand? For me, this is the meaning of human activity. I have been asked: why do you do this? Or: why should you do that? I was once told: You speak this way because you are a Christian and because you believe in God. But I knew people who were non-believers, I knew others who had barely heard of Christianity and who did exactly that. The great thing about it is that such activity needs no justification or proof of its usefulness. I believe in God, but I am probably a bad Christian because there are people I despise. If I said that I didn't, I'd be lying. True, I have noticed that I despise not those who are usually despised by others, and not for what people are most often despised for. But the vast majority of people should be pitied. That is what peace should be built upon. We, that is, those who think like me, have often been called lunatics. Many of those who talked like that are long gone; their names and what they thought was right and necessary have long been forgotten, but we still exist. And I think that as long as the world stands, it will. And in the end, it may not matter so much what it will be called: humanism, Christianity, or something else. The essence remains the same, and that essence lies within the fact that such a life as I'm telling you about needs no justification. And I'll tell you more – what I believe myself: this is the only life worth living".

Gaito Gazdanov, "Pilgrims".

Gaito (Georgii Ivanovich) Gazdanov, 1903 -1971