Today is the anniversary of the Victory Parade of 1945 on Red Square in Moscow. Why was the road in front of Marshal Zhukov marked with white paint? How could sappers be distinguished from miners and infantrymen by the sound of their footsteps? What did the sailors do to keep their berets from being blown away by the wind? Russian artist and engraver Vladimir Nuzhdin, who created the unique “Victory Parade” diorama, told the “Nuremberg: Casus Pacis” project about all of the above and the difficulty of portraying the largest parade in Russian history.

– Vladimir Nikolaevich, how did the idea for the diorama come about?

– In 1991, after my first exhibition, Gennady Andreevich Fedorov, the director of the Central Museum of the Armed Forces of the USSR, asked me to create a work depicting the Victory Parade. He provided all the necessary materials, asked me to watch a black-and-white film about the parade, which is kept in the museum's collection. I must have watched it about ten times in the cinema, then I was given a cassette and learned the film by heart – I must have seen it 500 times. Then, I remember, I deliberately went to Red Square and counted it by steps so that I could imagine all the distances and the scale accurately. People in plain clothes came up to me at the time and said: "What are you doing here, young man? I was indeed still a young man. I told them what it was all about: "OK, go on and count.” And I walked up and down and counted.

I made drawings, designs, sketches, and outlines, prepared all the papers and handed them over to Fedorov. We discussed everything in detail and he said: "OK, we'll do it by the 50th anniversary of the Great Victory.” And just a few months later, the USSR ceased to exist, and along with it, our funding. Fedorov was director of the museum for a few more years, but we never got back to this project. I left and worked for several years on orders from Western collectors because there was virtually no demand for my work in our country.

More than ten years later, I took part in a Moscow exhibition held by the Suvorov State Memorial Museum. At the opening, the new director of the Museum of the Armed Forces, Alexander Konstantinovich Nikonov, came up to me and said: “Are you Vladimir Nikolayevich Nuzhdin?” – “Yes, I am” – “When I was sorting out my office, I found a big package of documents and sheets of drawings. Did you do this?” – “Yes, I did for the 50th anniversary” – “Well, why don't we just do that project again?” And we agreed to do the work by the 60th anniversary of Victory, over just two years! We had to put off all orders and stay in the workshop for two years because it was a matter of principle. The Museum of the Armed Forces, of course, was very helpful: Heroes of the Soviet Union came to see me, including parade participant Ivan Ivanovich Dmitriev, who described how the parade took place and where he stood.

In April 2005, the diorama was finished, and three days before 1 May we took it out of my flat in St Petersburg, where I was finishing work. The diorama would not fit through the door, so we pulled it out through the window – good thing I live on the ground floor. There is a whole NTV channel report about it.

– The diorama depicts a real event, but of course, there is some room for manoeuvre in any artistic work. To what extent did you strive for accuracy?

– I tried to maintain the size ratio as much as possible, to create perspective and to comply with the s;cale, which we defined as 1:50. The size of all the figures in the diorama, from headgear to feet, is 32 mm if you convert this combination to human height, you get 170-174 cm.

There were 12,500 people on the Square, but I only made 2,000 mini-figures – as many as I had time to make in two years. I had planned to make 6,000, which was half the real number, but I was extremely pressed for deadlines. If I had had another year to spare, I would have done them all. The arrangement and details were taken from a black-and-white film, and the painting from a colour film, which was shot on a trophy tape, and was promotional in nature, so it was heavily cut down, but to understand the colour scheme it is sufficient.

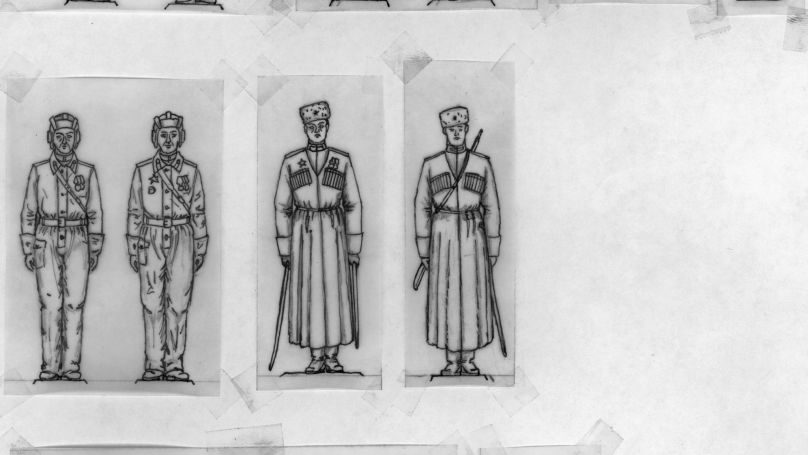

During my work with the material, I learned many details which are scarcely mentioned elsewhere. For example, everyone in the front rows wore parade uniforms, and the ones behind them wore field uniforms because the parade uniforms were made to order and they simply did not have time to make them all. Even many aviation officers were in field uniforms. My consultant, Ivan Ivanovich, was a Hero of the Soviet Union by that time, but he did not get a parade uniform either.

I learned from him that each "box" had a different sound when marching on the pavement. That is, a box of sappers, a box of minesweepers, and a box of infantry were shod differently. Some hammered in a nail to the head, some put them in more loosely, and some did not put one nail in at all, and so the “tapping” sound was different for all of them. I could never have imagined such a thing!

According to Ivan Ivanovich, they had five invalids in their "box" alone. Of course, they were not armless or legless, but wounded, limping soldiers. A decorated serviceman, who’d made it through the dogs and the quicksand – how can you refuse him? They were specially put in the centre of a " box" and when the soldiers passed by the mausoleum the line was closed, neighbours to the right and left shouldered and almost lifted the lame soldier, who only pushed off with one leg. This moment was purposely practised in rehearsals: it was important to encourage the wounded comrades and at the same time not to shame the honour of the front.

At the first rehearsal, the horse of Marshal Konstantin Konstantinovich Rokossovsky, who commanded the parade, skidded on the wet paving stones and literally rode past by Marshal Georgy Konstantinovich Zhukov, who reviewed the parade. That is why later on, the entire road was sanded and white circles were drawn so that the military commanders could stop at a certain point and salute the fronts. This moment is also depicted in the diorama.

The sailors at the parade only opened their banners a few metres before the mausoleum, so that the wind would not blow their navy cut caps off. And even then the standard-bearers lost their cut caps on Red Square!

The fronts were clearly scheduled by order, ranked by the number of generals, officers and privates. I used to remember by heart all the numbers in every "box". And still, there were more people than there should have been! We were Russians, not Germans – we could find a way to get through the eye of a needle. In some places, we had a three-man banner group from each flank, and in some places a two-man group, but we were supposed to have one! And that was in every "box", and I am not talking about the front.

But the most expressive thing, perhaps, that nobody noticed in the movies is that our ace pilot Alexander Pokryshkin had the so-called bow banner (strap, bandage for the banner) fixed not on the right shoulder, like everybody else, but on the left, so that the three stars of the Hero of the Soviet Union and the Order of Lenin were seen. This was the only clear violation of the regulations at the parade.

The parade participants went to the square long before it started and got all wet because there was a cold drizzling rain with a little wind. But no one felt it – as Ivan Ivanovich told me, everyone's adrenaline was pumping high.

– And how closely did you try to achieve the outward resemblance of the characters?

– I did everything I could. I painted the first row of orders and medals ("iconostasis") exactly like in the film, and then, of course, not - I won't lie, but I still tried to make each character different from every other one. I also tried to achieve a portrait likeness as far as it could be achieved on a “head” smaller than a match head. Marshal Leonid Alexandrovich Govorov, the commander of the Leningrad Front, looked very much like in real life, Pokryshkin looked like himself in the engraving, and then there were many charismatic and recognisable people, especially in the front row.

– What point in time does the diorama depict?

– 10 hours, zero minutes and 30 seconds. At precisely 10:00 Zhukov rode the stallion out of the Spasskaya Tower gate and I caught the moment when he and Rokossovsky rode towards each other. This was immediately followed by Rokossovsky's report as commander of the parade. All the same things you can see in parades today, except people riding in cars.

The back scene shows the State Department Store (GUM), the churches behind it, the State Historical Museum (SHM/GIM) on the left and the specially-built fountain at Lobnoye Mesto on the right. The viewer is supposed to be looking at the parade from the side of the mausoleum, that is, from the point where the Soviet leadership, led by Stalin, stood.

– And what are the technical parameters of the work?

– The work is 2 m 50 cm long and 60 cm deep and in height. When unpacked, it weighs 95 kg; when packed, it weighs 120 kg.

Red Square is made of wood, the backing is of course made of canvas, and all the figures are a five-component white metal alloy (tin, lead, zinc, antimony, and some aluminium). The painting is, of course, done in oil, because it is a more durable material that does not burn out. There are no technological intricacies in this diorama; it was made by hand, apart from the cast figures. I had some figures engraved in stone (a drummer, an automatic gunner, a boatswain, a sailor with a rifle, and so on) and then I cast each one in the required number of pieces using these moulds. But I painted them all differently, of course: some had one colour for their uniforms, others a slightly different one; the "iconostasis" was different, and the faces were different.

– How was your work received by the audience?

– When I brought the diorama to the Museum of the Armed Forces (the journey from St. Petersburg to Moscow was not without adventures), there was a state acceptance commission, as it should be. My senior comrade and teacher Pyotr Ivanovich Nikolaev, who went with me, was even more worried than I was, but everything went well. And then I relaxed, fell ill and came down with a fever.

On the day of the celebration, a large delegation came to the museum - President Vladimir Putin, eight foreign leaders, including US President George W. Bush, and two thousand veterans. Ivan Ivanovich told me later that the veterans were very happy and were expecting the author, but I could not come.

I can only say that, according to the hall keepers, they get tired of cleaning the glass because the children kept “clinging” to it and looking at the diorama for a long time. But that makes me happy: if the children like it, then it's all good.

– Is there anything you regret that you didn't have time to make?

–Of course, I do! I didn't have enough time to make as many figures as I had originally planned. For example, I didn't have time to make miners with dogs; I didn't have time to put machine-gun carriers in the corner at GUM. But I am still fixing some details: for example, I have now engraved two cameramen with cameras – and next year I will go to clean the model of dust – and will put them in the corners. It all adds to the charm of the work.

In St. Petersburg, the Tin Soldier Museum has an extended fragment of the diorama on display - there are only the Leningrad and Baltic Fronts, a total of 450 figures, but with more detail.

– Vladimir Nikolaevich, what other works of yours do you consider most successful?

– I can probably name “Suvorov Crossing the Alps”. It is the largest diorama in Europe, already made using modern technology. It is 6.2 metres long and 3.2 metres high, and the backing is a 7 by 4-metre canvas. Those Alps are a real sight to behold.

I am proud to have been commissioned by the Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts to work on the restoration of ‘Ivanov's Parade’. This legendary work depicts the last parade of the Russian Imperial Guard in St. Petersburg in 1914, just before the outbreak of World War I. The diorama was made by European engravers at the request of a Russian emigrant, who was himself a sailor and had miraculously escaped Nazi captivity. It turned out to be the largest parade in the world in terms of the number of positions (simply put, postures), because it is not static like my Victory Parade, but is a passing parade. I spent three years in Stockholm and restored this work, some of which I also had to finish – Ivanov didn't have time to commission engravers to make a marching band during his lifetime, and I finished the musicians myself. It was a very hard order.

And my last significant work, made for the 75th anniversary of the Great Victory is a creative work on the subject of the song “Zhuravli” (Cranes), which is kept in several collections. The theme of the Great Patriotic War is very important to me because my mother fought from the besieged city of Leningrad almost to Frankfurt.

At the moment, I only make creative pieces - I've done a lot of bespoke soldiers in my life, I’ve even lost count of the ones I've made.

The editors' team of the "Nuremberg: Casus Pacis" project express their gratitude to the Central Armed Forces Museum of the Russian Federation for the assistance in preparing the material.

By Daniil Sidorov