How the Nazis fought against the Church for the souls of the Germans and why they lost.

Initially, Hitler attempted to subjugate Catholics and Protestants alike. He sought to separate Christianity from love and compassion, and Christ from his Jewishness. He then attempted to create his own church under the wing of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, where the Bible would've been replaced with “Mein Kampf”. When that attempt failed too, Nazi ideologists mounted an open assault against Christianity and the faithful. One people, one Reich, one faith – that was the Nazi ultimatum to the freedom of conscience. And there also was to be only one god – the Fuhrer.

"Aryan Christianity"

The Nazi ideology was initially deeply antagonistic towards Christianity, which was born from the Jewish religion. The calls of Jesus Christ, a Jew, for compassion, the words of apostle Paul who said that "There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus" – they were incompatible with Nazi morals. Therefore, the relations between the Nazi Party and Christian churches were strained even before Hitler's rise to power.

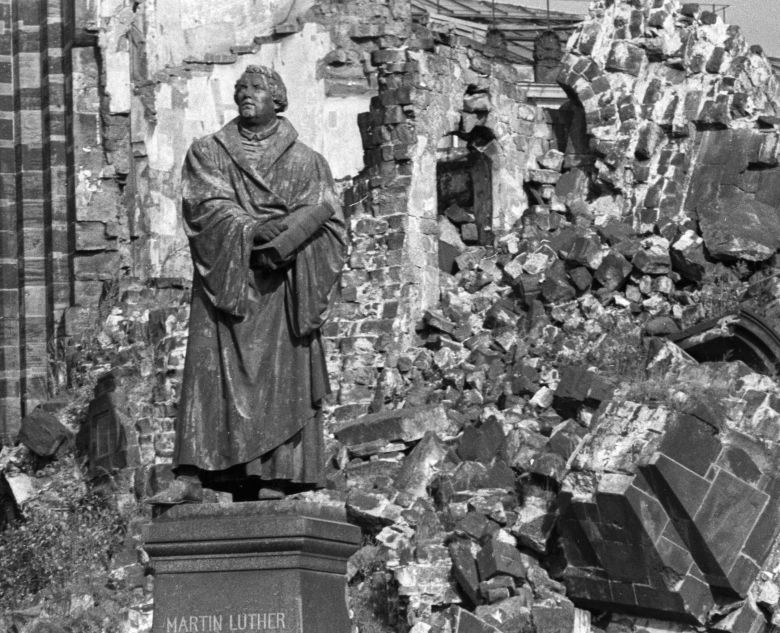

On the other hand, Germans are people with deep Christian roots. Germany was Christianised in the early Middle Ages, seven Popes were born there, and it was where the Reformation started in 1517. People in the northern and central regions of today's Germany became adherents of Lutheranism, while those living in the southern and western regions remained loyal to Catholicism, and gradually, respectful relations formed between the adherents of the different religious denominations.

One of the Nazi ideologists, Alfred Rosenberg, realised this contradiction. He fostered the ideas of so called “Aryan Christianity” which emerged in the 19th century and called for the cleansing of Christianity’s “Jewish legacy”, transforming it into an exclusive racial religion. Rosenberg claimed that the Jews, personified by the apostle Paul, had perverted the teachings of Christ, who wasn't a Jew at all.

As anthropologist Victor Shnirelman notes in his book “The Aryan Myth in the Contemporary World”, Rosenberg believed that Christianity should be cleansed from humility and compassion for the weak, while Christ should be made a hero rather than a martyr.

“The Old Testament, which was named 'Satan's Bible' by Hitler and which Rosenberg called to ban, earned a special enmity from the Nazis.”

Karl Maria Wiligut, Himmler's follower and an occultist who devised the rituals and symbols of the SS, was an even more radical supporter of “Aryan Christianity”. He considered himself to be a descendant of the ancient Germanic kings, and claimed that Christianity descends from the religion of ancient Germans who allegedly wrote the “true Bible” long before the Semitic people.

Faith and the "German Race"

However, at the beginning of their reign, the Nazis criticised Christian churches in a fairly moderate fashion, due to the fact that in Europe back then, the persecution of religion became firmly associated with the Bolsheviks. Adolf Hitler, who was raised in a Catholic family, noted in “Mein Kampf”: “A political party must never... lose sight of the fact that, as all available historical experience shows, no purely political party has ever managed to perform a religious reformation.”

Article 24 of the Nazi Party programme offered “freedom to all religious beliefs, as long as they do not threaten... the national feelings of the German race”, stating that the party “stands for positive Christianity”.

On 23 March 1933, three years after becoming Chancellor, Hitler delivered a speech at the Reichstag. He described Christian churches as an “important element in preserving the soul of the German people”, promised to respect their rights and expressed desire to improve relations with the Holy See. In such a way, Hitler sought to secure the votes of the Catholic Center Party.

War Between the Vatican and Hitler

On 20 July 1933, the Nazi government and the Vatican made a concordat which affirmed the right of the Church to autonomously “regulate its internal matters”. The document was signed by German Vice-Chancellor Franz von Papen and Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli, the future Pope Pius XII.

The Nazi government, however, started violating that agreement practically before the ink was dry, as US journalist William Shirer, who worked in the Third Reich and later covered the Nuremberg Trials, remarked. However, he noted, since said agreement was made at a time when the world was witnessing a wave of outrage sparked by the initial excesses of Germany's new regime, the concordat helped increase the prestige of Hitler's government, which the latter needed badly.

The peace between the Third Reich and the Holy See did not last. In 14 July 1933, the Nazi government adopted the “Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring” which provided for the forceful sterilisation of whole categories of German citizens. That act had greatly offended the Catholic Church.

By the spring of 1937, the Catholic clergy in Germany had lost all illusions. On 14 March 1937, Pius XI issued the "Mit brennender Sorge" ("With Burning Concern") encyclical whose original text was composed in German rather that in Latin as usual. The text was delivered to Germany in secret and read in all Catholic parishes in the country on Palm Sunday of that year.

The authors of the encyclical, including Cardinal Pacelli, berated the Nazi government for sowing the "tares of suspicion, discord, hatred, calumny, of secret and open fundamental hostility to Christ and His Church". While Hitler wasn't mentioned by name, it was fairly clear who exactly might be the “mad prophet” of whom, the Pope wrote, said in the Scripture: “He that sitteth in the heavens shall laugh: the Lord shall have them in derision”.

Hitler was beside himself with rage and promised retaliation against the Church. As Catholic historian John Vidmar notes in his book “The Catholic Church Through the Ages”, following the announcement of the encyclical, the persecution of Catholicism in Germany became even more severe. Thousands of priests, monks and laypersons were arrested, often on invented and fabricated charges such as “immorality” or “smuggling foreign currency”. The Nazi Party started disbanding Catholic youth organizations and impressing them into the Hitler Youth. Scores of Catholic publications were banned, and even the seal of confession was often violated under the pressure from Gestapo agents.