The attention throughout the Nuremberg trials was focused on the prosecutors, defendants, legal counsels, and witnesses. All the time, the judges remained in the shadows. However, on 1 October 1946, it was they who delivered the judgement that is now regarded as the benchmark decision all over the world. The editors' team of the “Nuremberg: Casus Pacis” project offers you the story of those who embodied international justice for Nazism.

Six In Robes, Two In Uniforms

Who were those men who handed down the biggest court verdict in history?

Seats for the members of the International Military Tribunal were placed in the Courtroom under the flags of the four powers (USSR, USA, UK, and France)

The selection of judges for the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg was not an easy task for the victorious powers. It was necessary to select people with not only great experience and authority, but also knowledge of international law, foreign languages, and the ability to find compromise solutions.

Mr Francis Biddle, Member of the Tribunal for the United States of America

The United States sent former Attorney General Francis Biddle to Nuremberg. He was not only distinguished by his considerable professional experience (he had been a lawyer since 1911), but also by his integrity. He was the only high-ranking official in the Franklin Roosevelt administration who, during World War II, opposed the Internment of Japanese Americans from the outset and later demanded their release. "The present practice of keeping loyal American citizens in concentration camps on the basis of race for longer than is absolutely necessary is dangerous and repugnant to the principles of our Government", he wrote in a letter to US President Roosevelt. At the same time, Biddle did not hesitate to prosecute socialists and other left-wing activists, as well as trade unionists. This drew criticism from American human rights activists. Arkady Poltorak, then the secretary of the Soviet delegation at the International Military Tribunal, recalled that at the trial Biddle “was very active, often asking questions to defendants and witnesses". One of the defendants, Franz von Papen, called Biddle "the best guarantee of a fair trial".

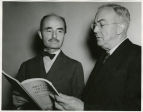

Judge Francis Biddle, Member of the Tribunal, and Judge John Parker, Alternate Member for the United States of America

Judge John Parker of North Carolina, another experienced lawyer, became Biddle's Alternate. The alternate judges at Nuremberg had an advisory vote, meaning they could not vote on important issues, but they actively participated in their deliberations, had the right to ask questions of witnesses and often offered very valuable ideas.

Justice Norman Birkett, Alternate Member, and Lord Justice Geoffrey Lawrence, Member for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, President

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland was represented by Lord Justice Geoffrey Lawrence, 3rd Baron Trevethin, of the Court of Appeal of England and Wales. Lawrence was not considered an exceptional legal talent in British justice and, as they say, was not the sharpest tool in the shed. Instead, Lawrence conducted his trials in an exemplary fashion, arrived at his verdicts impartially, and had no enemies. After Nuremberg, King George VI raised him to the peerage as Baron Oaksey, a second barony title.

Sir Norman Birkett, Judge, Alternate Member for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

The second British delegate, Sir Norman Birkett, was a far more brilliant figure. He had been a lawyer, a politician and a judge before the start of the Trial. The appointment as Lawrence's deputy was somewhat painful for Birkett's ego. Nevertheless, he contributed a lot to the work of the Tribunal - it was he who wrote the main part of the verdict. His merits were not immediately appreciated at home. Having received no honours, Birkett fell into depression for several months. Twelve years later Sir Norman finally received the title of baron and membership of the House of Lords, where he was active until his death.

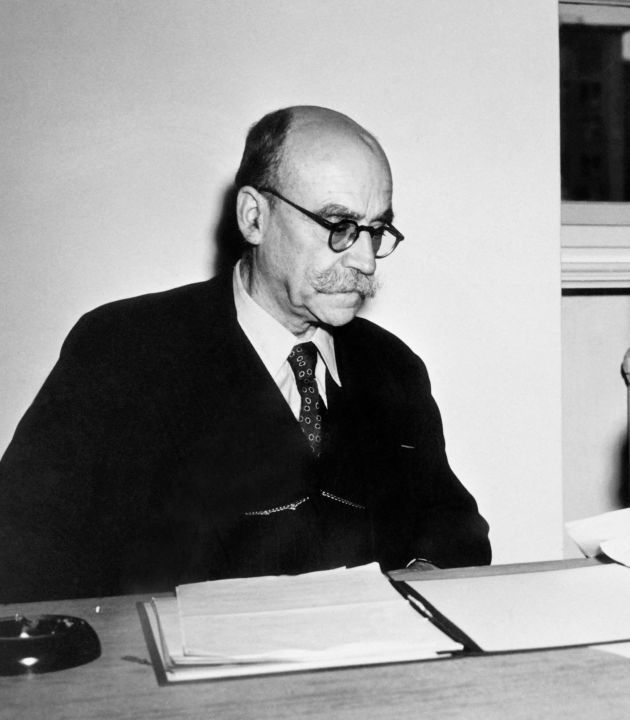

Henri Donnedieu de Vabres, a French jurist, Member of the Tribunal for the French Republic

The government of Charles de Gaulle sent Henri Donnedieu de Vabres, a university professor and distinguished specialist in criminal law, to Nuremberg. He sought to take a centrist position during the proceedings and became a “dove of peace” of sorts. Donnedieu de Vabres regarded the Soviet delegation's point of view as too harsh and the desire of the United States to dominate the process at the expense of professional, financial and logistical resources as dangerous. The French judge objected to the charge of crimes against peace, thought it wrong to condemn the military for following orders and believed that the best way of carrying out the death penalty would be by firing squad. However, he failed to achieve success on these points.

On 18 October 1945, the International Military Tribunal met in Berlin and adopted the indictment signed by the chief prosecutors from the USSR, the USA, the United Kingdom and France. From left to right: John Parker and Francis Biddle, Judges for the United States; Alexander Volchkov and Iona Nikitchenko, Judges for the USSR; Henri Donnedieu de Vabres and Robert Falco, Judges for the French Republic; President of the Tribunal Geoffrey Lawrence and Norman Birkett, Judges for the United Kingdom.

Robert Falco, a member of the High Court of Cassation, who was one of the authors of the Constitution of the International Military Tribunal, was appointed as the alternate judge to Donnedieu de Vabres. A lawyer of forty years’ experience, Falco was forced to resign in 1944 when the German occupation authorities drew attention to his Jewish origins. The chance to “pay back” the Nazis came a year later. During the Nuremberg Trials, Falco kept diaries, which were made public only in 2012.

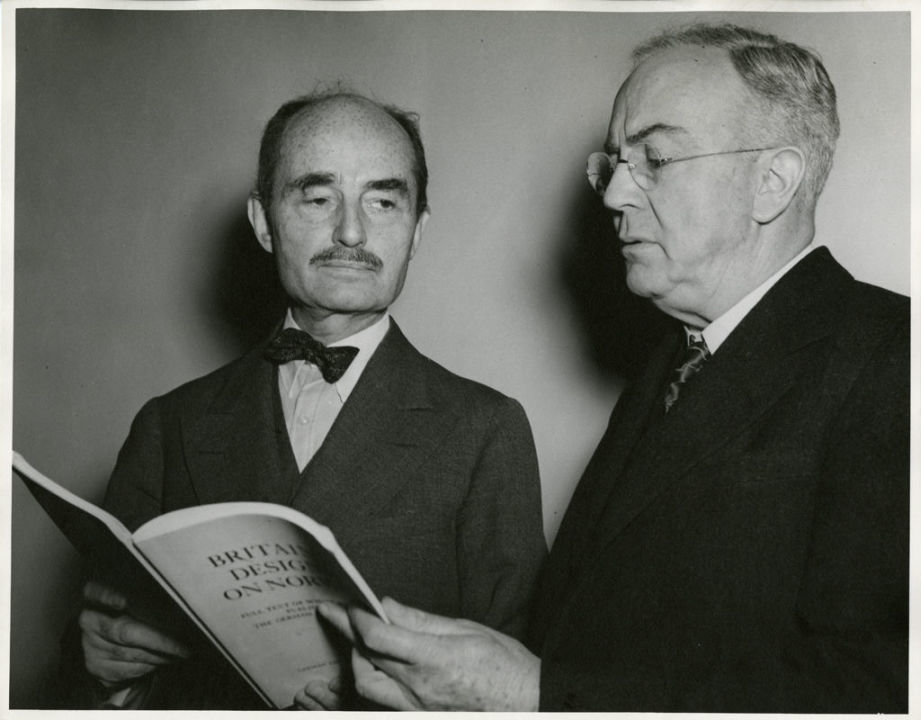

Major General Iona Timofeevich Nikitchenko, Soviet representative to the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, and Secretary of the Soviet Mission

The Soviet Union delegated Major-General Iona Nikitchenko, Deputy Chairman of the USSR Supreme Court, to the Tribunal. Before the Trial, he participated in drafting its Constitution and sought to combine the strongest features of Anglo-Saxon and continental law. His position was often in line with that of French judge Robert Falco. In the end, compromise solutions were found and many of the proposals made by the Soviet delegation were accepted. At the trial, Nikitchenko, as the representative of the country most damaged by the Nazis, also advocated the toughest line against the defendants. After the verdict was delivered, he issued a dissenting opinion in which he disagreed with some of the court's decisions as too lenient. Although the text of the dissenting opinion was negotiated in the Kremlin, it is notable for its clear legal wording, detailed arguments and lack of propaganda rhetoric. Ten years after the Nuremberg Trials, accusations against Nikitchenko surfaced in the Soviet Union relating to his involvement in the mass political trials of “enemies of the people” in the late 1930s. Many of those sentenced to death by him (very often Nikitchenko passed such sentences by telegraph) were rehabilitated. However, the role of the Soviet judge at the Nuremberg trials was never questioned.

Major General Iona Nikitchenko and Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Volchkov, representatives for the Soviet Union, at the examination of the indictment documents

Nikitchenko was assisted by Alexander Volchkov, who got accepted to the Trial because of his excellent knowledge of international law and English. He had served as a diplomat and lecturer before the war and during World War II was among the practitioners of military justice. Just like Nikitchenko, Volchkov was considered a hardliner.

The Judges table at the Nuremberg Trials. From left to right: Alexander Volchkov (USSR), Iona Nikitchenko (USSR), Norman Birkett (UK), Geoffrey Lawrence (UK, President of the Tribunal), Francis Biddle (USA), John Parker (USA), Henri Donnedieu de Vabres (France), Robert Falco (France).

The judges debated what uniforms they should wear for the proceedings. The Soviet delegation insisted that members of the International Military Tribunal should wear military uniforms, as is customary throughout the world. The Western judges preferred robes, which they believed were “more in keeping (...) with reason and dignity”. However, Iona Nikitchenko protested against “medieval gowns”. In the end, the judges allowed everyone to put on what they found appropriate. And no one donned a wig.

Four Judges of the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg, 15 October 1945. From left to right: Professor Henri Donnedieu de Vabres (France), Francis Biddle (USA), President of the Tribunal Sir Geoffrey Lawrence (UK), and Iona Nikitchenko (Soviet Union)

The question of the identity of the president came into sharp focus before the Trial began. The international courts used to have a rotating presidency, but this approach did not allow for a uniform style of proceedings. The Americans and the British did not want a Soviet judge as president. Francis Biddle did not mind presiding over the Tribunal and even brought with him a gavel presented by Roosevelt, but his compatriot Robert Jackson was already playing the first fiddle in the prosecution. In the end, Biddle, having secured the support of Donnedieu de Vabres, offered the post of president to Geoffrey Lawrence. When Nikitchenko, who was unaware of the behind-the-scenes arrangements, nominated Biddle himself, he politely declined in favour of the Englishman and simultaneously offered the Soviet representative to preside over the preliminary hearings in Berlin. This arrangement suited everyone. The calm, diplomatic and punctual Lawrence proved to be a very successful President of the Tribunal. He never raised his voice, but he conducted himself consistently and firmly, and no one questioned his authority. Biddle gave his gavel to Lawrence. However, a couple of days after the public meetings began, the item disappeared from the table - it must have been stolen by journalists during the break. It is said that a similar gavel was made from the photographs and the President never left it unattended again.

A reception hosted by Major General of Justice Iona Nikitchenko, a representative for the USSR to the Tribunal. From left to right: Alexander Volchkov, Geoffrey Lawrence, Iona Nikitchenko, and Norman Birkett.

Members of the Tribunal have met several occasions, not only in sessions but also informally.

Pictured in the group (from left to right): Oleg Troyanovskiy, interpreter; Arkady Poltorak, secretary for the Soviet prosecution team; Lord Justice Geoffrey Lawrence, Member of the Tribunal for the United Kingdom, President of the Tribunal; Major General Iona Nikitchenko, Member of the Tribunal for the USSR; Norman Birkett, Member of the Tribunal for the United Kingdom; Alexander Volchkov, Alternate Member of the Tribunal for the USSR; and others.

The Verdict of the International Military Tribunal had been debated since the summer when the sessions were still in progress. The final text of the judgment was the result of compromise on almost every point of the charges and defendant. Although the prosecutors, except for Jackson, had demanded the death penalty for all the defendants, the judges had not originally envisaged such a hard decision. The stumbling block was a different matter: life imprisonment for Rudolf Hess, the acquittal of the three defendants and the non-recognition as criminal organisations of the Reich Cabinet, the General Staff and the German High Command of the Armed Forces (Wehrmacht). It was these points on which Iona Nikitchenko expressed a dissenting opinion.

Courtroom of the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg

Regardless of differing judicial systems and ideologies, contradictions between the victorious countries and the outbreak of the Cold War, the members of the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg were able to arrive at a unified, balanced and carefully reasoned verdict. The text of the verdict became a model of justice and formed the basis of post-war jurisprudence throughout the world. The credit for this goes to all the judges.