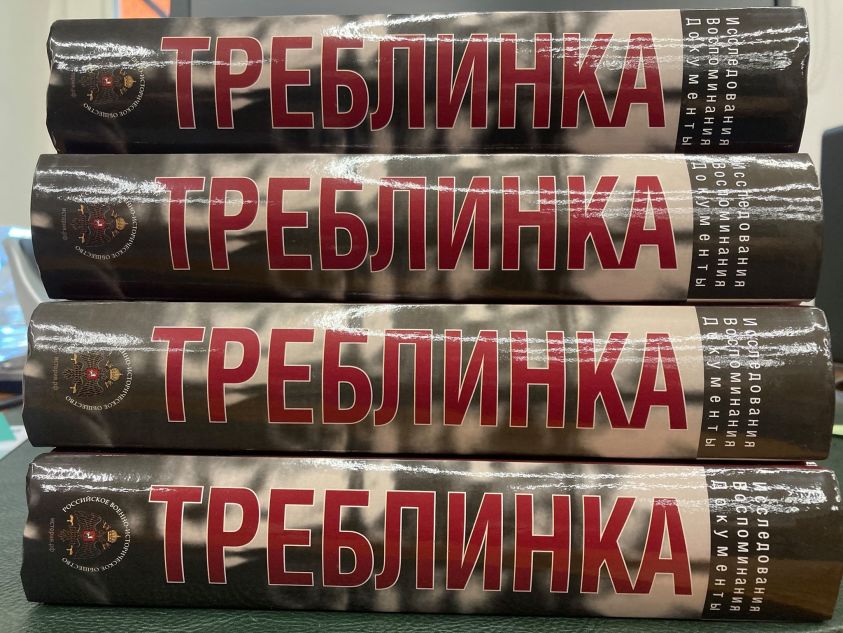

We continue our interview with the author of the idea of the book “Treblinka: Research. Memories. Documents” and executive editor of the publication, historian, associate professor of history at the Moscow State Pedagogical University, and deputy director of the Department of Science and Education of the Russian Military Historical Society, Konstantin Pakhalyuk.

Within the framework of the “Nuremberg. Casus pacis” project we have published several excerpts from the book, and now we are presenting you with the second part of the big and important interview about how one can cope with at times unbearable discoveries and how extreme situations can teach us the idea of peace?

- A quote from the book: “For train crewmen, Poles as a rule, it was also not a secret, whom and for what they transported. Train driver Henrik Gavkowski recalled in an interview with C. Lanzmann that people’s screams were well heard, it was very frustrating, and therefore, the drivers were given vodka”. “From the spring of 1943 local residents were regularly engaged to dispose of ashes, which were spread on the fields as well as on the road going to the labor camp Treblinka”. How did these people feel about what they were doing? Did they repent afterwards?

There were rare cases when collaborators, or wachmanns, either escaped or even attempted suicide. But in general, if we are talking about Trawniki men, they commonly showed no remorse. The case of the Poles is more difficult. If look at the film “Shoah ”by Claude Lanzmann, where he travels to the death camps and communicates with the inhabitants of the surrounding villages, who remember those years. It's a difficult topic for them indeed, but their involvement doesn't seem to bother them much. Of course, in the face of brutal occupation terror, it would be too idealistic to demand heroism from a common man, but even in the conditions of occupation, there was a choice whether to take belongings of Jews, whether to live in their homes, whether to benefit from their tragedies or not. After the war there was a choice as well – whether to condemn those who took Jewish property? The answers are obvious. And the absence of a post-war reflection on the subject is self-explanatory.

In the same Lanzmann’s movie we can see a train driver who confirms that he heard the sounds and took vodka. Such complicity was a part of the Nazi system. Many didn't take direct part in murdering. In the context of labor service, refusal could have led to very bad consequences, such as imprisonment in concentration camps or compulsory labor. Everyone had to make a choice, a terrible choice. Many agreed to be accomplices rather than victims.

Even years later people refuse to take responsibility as I think due to the inability to empathize with the suffering of others. And it is hardly surprising, especially with regards to a man of traditional, patriarchal culture. Compassion is rather a social skill associated with the Modern era, something that emerges in Modern culture. This skill requires a certain emotional sensitivity, and it is not a part of human nature; it must be developed.

The book includes testimonies of the prisoners of the labor camp Treblinka I. For example, there is a very curious story by Vanda Pavlovskaya, who told about how she got into the camp. Her sister and she decided to see what was going on there, they took bread with them just in case, there were only Jews; they came from the forest on the back side, and behind the wire they saw about 20 people, who were uprooting stumps. But in 1943, all the locals were pretty aware of what was going on in the camp, because of the smell of burned bodies and fires. Accordingly, we understand that they went not to satisfy curiosity, but to sell bread to prisoners, and they got caught.

Here we face an important obstacle preventing us from making unambiguous assessments. On the one hand, the fact of engagement in corruption and enrichment at the expense of those sentenced to death is pretty clear, but on the other hand, this barter trade facilitated the situation of the prisoners. Talking about the camp itself we face the same contradiction. Samuel Willenberg described the winter of 1943, when the trains with deportees stopped arriving and the prisoners began to starve. When the first echelon arrived from Bulgaria, everyone understood that people there were doomed to death, but they were happy because the deportees had food in their suitcases.

From the interrogation report of Kazimierz Skarżyński on the construction and operation of the Treblinka labor camp and the killing of Jews in the death camp. Village of Vulka-Dolna, 24 September 1944.

“In July 1943, the echelon stopped near the village of Vulka. The heartbreaking voices of people pleading for water could be heard out there. The population of the village tried to give them some water, but the wachmanns started shooting. Then, men, women and children who were in the cars of the train began to break down the walls and jump out. The wachmanns shot these defenseless, thirsty people. 100 people were killed that day. Four children who died of asphyxiation were also thrown out of the cars, there were no signs of gunshot wounds. The wachmanns fired explosive bullets. It was clear from the injuries. All the 100 murdered Jews were buried by the local population in our village in Vulka. Within the year, there were clouds of smoke over the camp, and at a long distance several huge bonfires were visible. We, the residents of Vulka, could hardly breathe fresh air during this year. The stink of burning human flesh filled the whole area. Every 3 - 4 days, a train from 3 to 20 wagons transported the ashes to different places near and far from the camp. I myself often had to transfer those ashes on the orders of the Germans from the places where they were unloaded. Even now, a year after this death factory was closed down, huge masses of ashes can be seen on all the roads close to the camp”.

Many people try to distance themselves when they witness evil. We are talking about the extreme situation when traditional approaches to morality have to be abandoned. Do you remember the example from the book about the people who were next to a train and saw a woman who had her hand with money cutoff or a child being played like a ball? But let’s remind ourselves that even nowadays the mother of the Maniac of Skopin was aware of two girls who were kept by her son in his basement, who raped them for years. However, even after the arrest of her son, she claimed that he had been punished for nothing, that he was not guilty, because there were prostitutes who deserved it. I think that the parallel fits the occasion, and we’re coming up with universal patterns.

I just recently read two books of memories. The first one was written by Hungarian Jew Edith Eger. She was a prisoner of Auschwitz, survived a death march, returned after the war, married, escaped from the Soviets with her husband and ended up in the United States, where she became a prominent professor of psychology. She is still alive and she wrote her book ``The Choice”. And the second one was written by Ekaterina Martynova who had been a prisoner of the Maniac of Skopin for four years. Many parallels can be drawn between these memories. In both cases we are dealing with young girls in extreme situations (although, in the first case we are talking about State terrorism, in the other one - about an individual criminal). Both had their torturers, Mengele and the maniac, who were hated, but still they had similar reflections on their motives, claiming that internally, spiritually, they, the victims, were far freer than the torturers. They had similar survival practices - the memories of family, everyday things, God etc. Identically, they couldn’t tell the story of their experiences after they had been released. And then it becomes important for both to share their stories with others. They try to convey it as a guide for those who may find themselves in such a situation as evidence of choice, self-preservation and resistance, which is possible even in such circumstances. This indicates that the extraordinary experience created by the concentration camps is unique in terms of history, but not in the context of other extraordinary circumstances, when your identity, your subjectivity, shaped by cultural, social, legal systems, is suddenly overturned, when you’re not an individual any longer, but just a naked body suffering various manipulations. Experience of living in extreme conditions, resisting it, and then overcoming the trauma - that’s what you can learn from these stories. These experiments are incomprehensible and unimaginable in normal life, but the actual “normality” and not conceivable without the understanding of“emergency”.

- So these are the stories that should inspire us in some way?

- That’s true for personal behavior strategies. But we can’t apply it when looking in the past in order to understand the world. We need to be careful in my point of view. Regarding the war era, today we are trying to see it as a role model, but here we face a problem. Learning role models from extreme situations we have to keep in mind that it can be applied to an extreme situation only. And whatever models we choose for ourselves in it, it is still models of behavior for emergencies, not just for peacetime. Such heroism in all its glory is not applicable in peacetime. Numerous heroic stories, which are taught at schools today, can prepare for a war situation. But they are insufficient to provide guidance for behavior in a peaceful, normal society, especially as dynamic as today’s one. The same applies to Holocaust, the issue of involvement in evil, morally, can’t be brought to our peaceful time; otherwise we can turn into “Morality Police”. That is why individual manifestations of “new ethics”, which was partly developed from discussions on the Holocaust, begin to resemble “party meetings” from the Soviet era. The same problem arises when we look too much at the military history of the Great Patriotic War and try on that basis to imagine what a normal society, a normal policy, a normal power or a normal ruler should be like. This is a common but wrong track. Such a social imagination leads to the maintenance of a sense of emergency.

Again, I am not talking about the irrelevance of history, but I urge, that on the basis of historical material we raise another question - on the balance between extraordinary and normal, as the search for normality - ethical, social, cultural, political - is the number one issue now, both globally scale and in Russia. Giorgio Agamben, philosopher, once noted that the creation of “emergency situations” is one of the key practices of the modern world to maintain control. He gave the example of Western democracies. But still we are now living in a society where extraordinary situations are much more often than normal. Russian political scientist Gleb Pavlovsky considers the creation of extraordinary situations the key issue of modern Russia. But it is difficult to understand the concept of extreme and normal in the modern world apart from historical examples. So, by looking back at the history of emergencies, even those that are not directly relevant to us today, we can try to understand how emergencies actually work and therefore, how normality works as well. But the results of such judgments can be learned from the past, and they cannot be directly implied to the present day. Thus, the history of Nazi crimes includes the history of relationship between human beings and the criminal system which creates piles of corpses and captures peoples. At the beginning of the third decade of the twenty-first century, the vast majority of the world’s population lives in political systems that are not criminal, which means we still have to live on our wits.

From the interrogation report of Geni Marchinyakovna on the construction and operation of the death camp Treblinka. The village of Kosów Lacki, 21 September 1944.

“One Jew from Węgrów, I don’t know his last name, 17 year-old boy, brown hair, with obvious signs of exhaustion, couldn’t stand the beating and fell unconscious. The Commandant, I didn’t remember his last name because he was in the camp during the two months of construction only, June and July, was standing next to him until he regained consciousness. In front of everyone, as a “punishment”, the exhausted boy was ordered to go down to the well and get a bucket. The young man went down there and collapsed. With difficulty he got from there and as the “guilty” he was taken to the forest and shot there”.

- Is it even possible to judge the past?

- Any public debate - that is a non-academic debate about the past - is first of all a debate about values which focuses on covert moral judgements. When we discuss heroism, we make moral judgments. When we discuss heroism, we make moral judgments, and when we discuss traitors we do the same. The same applies to monuments, memorial tablets, the Immortal Regiment. We have been following this path for a long time, I'm not saying that we should suddenly become silent. Saying that something is “too difficult” means the refusal to think. On the contrary, you have to learn to have a public dialogue with the past.

-It’s easy to talk about the past, when you know the outcome...

- Yes. It’s an advantage. For example, as scholars write, that today World War II is always seen through the prism of a tragedy, especially abroad. What does that mean? Do they talk about tragedies more? – No, not at all. The tragedy here refers to a particular type of perception resembling the literary genre of the same name, when you see that something goes wrong, and through empathy to the protagonist you can reach a catharsis - a purification of your feelings. In the case of understanding the history “through a tragic narrative”, you ask yourself: don’t you repeat the path of the main hero? Don’t you repeat his mistakes? And the very possibility of this perception exists only because of this “post knowledge”.

- In this case, we face a temptation -not just to reflect on the issue but to judge. While some facts clearly deserve to be considered, the other more controversial (such as the involvement of silent locals or apparently lenient decisions of the judges) can be really misleading. Which measures should be applied?

- The same way as it was done by Hannah Arendt, I would offer to share the blame and the responsibility. Guilt is a legal issue, involving judicial procedures and law. Responsibility is a political matter, involving a person or a group of persons, or even an entire nation, which shares the ideas it applauds to and supports those it votes for. If a person is beaten next to you, then legally you are not guilty, but if you distance yourself–morally you become responsible. The same is true for politics. We cannot be guilty of what politicians do on our behalf, but we are responsible for it. Even if we don’t applaud, we’re still present.

This harsh and unpleasant conclusion has been drawn including from the history of Nazi crimes. Of course, it’s hard enough to prescribe what to do if a crime has been committed, corpses or ashes are present, and you didn’t kill yourself, but still you were there. You can’t bring back the dead, you can’t put ashes on your head again and again, but it’s also unethical and dangerous to just step over the past and the history. Not everyone is ready to admit his own responsibility for the crime publicly, like it was done by like Oscar Gröning, an accountant from Auschwitz. But that is exactly why we need to talk about the Nazis and why we need to justify the intransigence of punishment. Even if you are 100 years old, you may be prosecuted sooner or later to cool modern hotheads. And, of course, if you don’t ask these questions, few people are willing to judge themselves morally.

- A quote from the book: “Among other things, she cites a case when a Pole in the first half of 1943 apprehended a young woman who had escaped from a train to Treblinka. He handed her over to the Germans and she was shot. At the court in 1951, he stated that he did not see anything wrong in his act, as he allegedly could not predict such consequences. The court acquitted him”. Which arguments, if any, were put forward by judges in such cases?

- This information came from a secondary source, from a scientific article, but it is clear that such people could not have been unaware of the consequences. It was common knowledge that the Germans shot and killed Jews. Denial in this case is nothing but hypocrisy. The logic of the Court is clear - in evacuation conditions, a person is subject to orders and rules established by the occupation authority. But, on the other hand, the Pole could just ignore that Jew. Remember the chief of Petrishchevo village, who could have just kicked Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya out, but he decided to tell the Germans about her instead. Didn’t he know what was going to happen to her? He did. And this gives us an insight into his inner perception of the situation in that time - - in the autumn of 1941, he thought that the Germans were going to win. He wanted to score points with the new authorities. The same way the Pole thought he did the right thing.

From the interrogation record of Wolf Scheinberg on the German atrocities at the Treblinka labor camp, 22 September 1944.

“What I remembered best was the extermination of prisoners:

1. On 9 November 1942, six prisoners with one wachmann went to work in the forest, where they killed the wachmann, took his rifle and fled. When this was discovered in the camp, 110 prisoners were taken from the camp behind a wire fence. 9 SS men and 100 wachmanns taking shovels, axes, sticks, knives, the favorite murder weapon, went behind the barrier as well and began the horrific beating of defenseless people. The prisoners were beaten with sticks, axes, shovels and knives. The ground was covered with blood, pieces of flesh and human entrails were lying around, there were sounds of bones being broken, and there were still some shapeless pieces of human flesh still moving on the ground. There were heartbreaking screams over the camp that could not be silenced by the song that the SS men and wachmanns sang at the time of the massacre. I remember a few words from this song, translated into Russian, they meant something like this: “Let Jewish blood flow down the knife”. When the beating was over, it was hard to recognize those people. They were just pieces of flesh. The SS men and the wachmanns, covered in human blood from head to toe, looked very pleased with themselves.

2. On several occasions I witnessed the mass execution of prisoners by drunken SS men and wachmanns, it was directed by Hauptsturmführer von Eipen, when a drunken mob approached the barracks where the prisoners rested, opened the door and opened the indiscriminate shooting of people, 50 to 100 people were killed at a time. I’ve seen that myself three times.

3. In June 1943, von Eipen brought about 1,500 Jewish women from Warsaw, of whom 30 the most beautiful were chosen; the rest of them had their valuables taken from them and were sent to the camp no. 2, where they were exterminated in the “bath”. Thirty Jewish women were distributed between SS men, and for a week they continued to drink and to rape those women and girls, after what they were all killed.

4. I witnessed the case when Untershafteführer Schwarz and Preiffe bet that Preifi would hit a man in the heart from 50 meters away. So, they went out on the street where the prisoners worked and waited for one of the workers to turn his chest towards them, and when a young Jew turned while he was working, Preifi shot him with a pistol. There was another case: one day the workers went to work in the afternoon. An elderly Jew came to Preifi and asked him to be excused from work until the morning. Preifi smiled and said: “You are weak, give me a shovel”, and, having taken a shovel from a Jew, with a strong blow he cut the prisoner’s head to the neck. In January 1943, Preifi noticed that one prisoner was moving his jaws while going to work. Preifi approached the prisoner and said: “What do you eat, open your mouth”, and when the prisoner did this, Preifi shot him in the mouth. Preifi’s favorite entertainment was when he opened the window of his room and shot the prisoners who stood in a group while working; sometimes he killed dozens of people.

5. In mid-August 1943, on another bender, von Eipen decided to ride on a horse and put his 4-year-old son on his knees; he was brought to the camp on that day. A large group of women were returning from work. Upon seeing them, von Eipen sped up and crashed into the group of women, more than 10 women were killed, and several dozen women who tried to escape were shot dead by wachmanns. On 5 May 1943, von Eipen had a party at his apartment, demanding one beautiful woman and the famous Polish pianist composer Kagan, who was imprisoned in the camp. In the morning, Kagan and the woman were killed so they could not tell what was going on at von Eipen’s apartment. It was not a single case of extermination of Jews, but a systematic extermination of the Jewish population”.

- Quote from the book: “I am well aware that during my service in Treblinka, every single wachmann was involved in shootings, beatings, and in killing people in gas chambers, as it was our daily duty. Moreover, so many people were killed, so that unpleasant work was impossible to avoid”. It is obvious that the vast majority of SS men and wachmanns who killed people daily were sadistic sociopaths. Do you think the top authorities realized that Irmfried Eberl* and others like him were sadists? Was it the conscious use of sadists? Or did sadism become the norm? Were there any internal rules, at least on paper, intended to regulate “extra” violence? Were there any punishments for “abuse of authority”?

(*Irmfried Eberl –first Commandant of Treblinka, psychiatrist, Head of the Euthanasia Centre of the AktionT4 Mass Destruction Program. He himself opened the crane of the pipe supplying carbon monoxide to the chamber during the gas testing. Was known for his extreme cruelty. Subsequently, witnesses-employees quoted his dream of “killing God and the whole world with gas”).

- If we are talking about a regular concentration camp, any punishment of prisoners had to be formally agreed by the management of D department (inspection of concentration camps). Of course, this ruling was never carried out, or decisions could be negotiated after the fact. Treblinka, like Belzec and Sobibor, were labor camps, which functioned as a special world with no rules. One has to understand that the SS itself had never encouraged sadism; the perfect image of an SS was a man with a cold heart, a good mind and clean hands who honestly did the dirty work entrusted to him. It’s a kind of bureaucratic ideal which was promoted by Himmler. While in the practice, we see a whole set of behavioral strategies. There were people like Kurt Franz, Franz Stangl, who tried to distant themselves, and they really did it to a certain extent. There were, on the contrary, such people as Oberscharführer Franz Suchomel, who was not a sadist, but he didn’t mind participating in what was happening and tried to justify himself by virtues: he did it as he was a virtuous son, a virtuous warrior, a virtuous performer. In fact, and I think it’s very important, the history of the Nazi concentration camps is full of examples where virtue serves as a cover for immoral behavior. Of course, no matter how the officers of the extermination camps behaved, they can’t be justified. They knew what they were doing anyway. The inner senses of these killers are scientifically interesting, but they are hardly important for a legal or public assessment of their actions.

From the interrogation report of the witness Gustav Borax on the death camp of Treblinka and the work of the team of barbers. Vengruv, 3 October 1944.

“Many women sat on benches in the barbershop holding babies. There were cases when women were breastfeeding their babies when they were having their hair cut. Children were screaming. The barbershop was filled with cries and screams. Many women were pregnant. Some of the women were bleeding, so there was blood on the bench. It was terrible. Some women and girls went crazy, and it was common. I remember a case, when a beautiful 18-year-old girl from Grodno, seeing the dreadful conditions of the barbershop, went mad immediately. There were many cases of crazy women singing, tearing their faces to blood, pulling their hair out and lashing out at the Germans. Mothers cried over their daughters and granddaughters when they were still alive. There were such terrible moments. The hairdresser Bosak, who arrived from Częstochowa, took poison and died after the first day of his job. (...) The Germans selected the most beautiful and the youngest women and took them away for their sexual needs. I remember when the Germans took more than 30 women at once for this purpose. Naked women were searched as the Germans looked for valuables and money. Every woman was asked to spread her legs. A special person checked if there was anything hidden in women’s genitals. Mouthes and ears were also checked. This humiliating examination was supervised by Unterscharführer Suchomel”.

Their management was primarily concerned with efficiency of the destruction and delivery of valuables left from dead people. Accordingly, high-ranking SS officials were more concerned with total corruption; they didn’t want it to cause obvious damage to the interests of the Reich. The very organization of the extermination process in the camps was intended to protect the Germans from the moral suffering they endure while killing the innocent during the shootings. In 1941, Himmler saw the shooting of innocent women near Minsk, he was shocked and decided to find a way to reduce the number of people directly involved in murdering to alleviate their moral suffering. As a result, the Nazi extermination machine was built as a manufactory: some propagate, others plan, some take the Jews to the extermination site, some guard them, some escort them into the gas chambers, and others, as in Treblinka, turn on a tank motor in the chamber. This division of responsibility provides huge opportunities for self-justification. Moreover, the “engine” itself was started by Trawniki men - collaborators. So, of the 800,000 Treblinka victims, only a small number of people were technically killed by the Germans. But we understand that this is a matter of the system’s work. And the specific notions of self-righteousness, supplemented by propaganda, which deprived those doomed to death of their human faces, greased the gears of this death machine. The SS convinced the executors that they were carrying out an extremely important state task, the will of the Fuhrer! Remember Christian Wirth, inspector of the extermination camps, when in August 1942 he restored Treblinka’s work – he beat not only Jews, but SS men as well. It was the system of total obedience.

Samuel Willenberg - a Polish Jew, an artist, sculptor and writer, who survived the Holocaust. He worked in the Treblinka Sonderkommandos, and participated in the uprising in the camp. He fled, participated in the Warsaw Uprising, and immigrated to Israel. He was awarded all the most important orders in Poland. The memoirs “Surviving Treblinka” were published from 1986 to 1991 in Hebrew, Polish and English. At the time of his death in 2016, Willenberg was the last surviving member of the Treblinka revolt.

From the memoirs of Samuel Willenberg - “Surviving Treblinka”:

“After the arrival of a transport from Warsaw, one little girl was left alone on the platform beside the adjacent hut. Her age was hard to ascertain. The torn rags which covered her delicate, slender body had apparently been a dress at one time. On her head was a pretty kerchief; she gnawed at its fringes with her white teeth. Her large, doe-like black eyes flashed about in fright. Her skinny legs were red from the frost, and her feet were sheathed in gleaming shoes with very high heels, in stark contrast to the rest of her miserable attire. She had evidently acquired these from someone in the ghetto who had taken pity on her; or perhaps she had found them in an empty flat. She was clutching a partly eaten loaf of bread to her chest, as if afraid that someone might steal it from her. That chunk of bread - how had she obtained it in what we knew as starvation ghetto? — was her total wealth. With her frightened eyes she gazed at the platform and the wagons pulling away from it. A figure appeared at the gate in the barbed-wire fence with its inter- woven pine branches. It was August Miete of the SS, striding onto the scene in the high boots which disguised his crooked legs. We called him the Angel of Death. Creeping like a cat, a smile of satisfaction on his dull, fair, moustachioed face, he stealthily approached the new prey. Reach- ing her, he pushed her gently, almost imperceptibly, as if not wanting to dirty his murdering hands. He pushed her as a child might push a large ball, prodded her with a stick so that she might start rolling by herself. Thus the Angel of Death led her to the rear gate between the two huts abutting the platform. He propelled her toward the sorting-yard and the innocent fence at its edge, with its pine branches. Behind it was the Lazarett. The sorting-yard overflowed with giant piles of clothing. As the Angel of Death nudged her along, the girl stepped into the yard with her red shoes, heels sinking into the sand. Like an apparition from another world, she approached the sorters one after another, glancing at the contents of the suitcases as if she were browsing around a market. She wandered among us, showing us a gentle smile and terrified eyes. Stopping at one of the suitcases, she withdrew kerchiefs of various colours and flung them into the air, as if dancing. Work came to a halt; everyone contemplated this strange specimen of Warsaw misery. She roamed from one prisoner to the next, one bundle to the next, one suitcase to the next. In every suitcase she found something, tossed it into the air and went on. She stopped beside one suitcase and pulled out a pair of glasses, part of the rich collection of spectacles assembled from the belongings of so many who had been exterminated by gas. Suddenly her skinny face froze with fear. Terror seized her whole body, driving the madness from her. She seemed to have become a normal person. She clutched the glasses of a small child, gazed at them with disgust and threw them into the sand. Her eyes radiated a terrible fright. She looked at us, at the prisoners, at the whip-toting foremen and the SS men strolling around the yard. She contemplated us with the intuition of an animal who senses that its end is near. She began to step back, to distance herself from the towering multi- coloured mountain. The terror in her eyes grew. Miete approached her and pushed her toward the opening in the green fence with its flapping Red Cross flag. No one said a word. The foremen stood with their heads down, their whips slack. The prisoners stopped working. Everyone watched the little girl from Warsaw as the Angel of Death, Miete of the SS, pushed her towards the Lazarett. She vanished behind the fence. A few minutes later we heard a shot. Silence, utter silence everywhere. Then Miete strode back through the gate, slipped his pistol back into its black holster, and slapped invisible dust from his palms. At that very moment, as if by order, the Kapos and foremen began howling, spurring the prisoners back to work. Their voices hit us from all sides: ‘Work, you bastards! Schnell! Schnell! Whips sliced the air above our heads, The noise, we knew, was not meant for us. It was the only possible way of protesting at what we had just witnessed. Thus we paid the little girl from Warsaw our last respects».

- And yet, keeping in mind the famous rational coolness and some squeamishness of the Nazis, why was the destruction not limited to impersonal destruction? Why were these wild practices of physical humiliation? After all, even according to the Ordnung system, such things were to be qualified as corruption of personnel…

- Again, bullying was not obligatory, but it became a way of ensuring order. Technically, they had a very difficult task: they had to kill tens of thousands of people every month, several thousand a day. This is a huge number of people, and you have a few dozen SS men and about a hundred Trawniki men. Even though they were well-armed – it was not enough. That’s why deportees had to be turned into obedient crowds. Accordingly, you use a combination of false hope (“We are relocating you to Ukraine'') and terror. The closer we get to the gas chambers, the less false hope and more terror we apply. It was important to do everything in a hurry, so that people didn't have time to look back, run away or resist. People travelled to the death camp for several days in overcrowded wagons with no seats, no food or water. Upon arrival, they were kicked away with screams and beatings. But still, SS men maintained the illusion that it was a regular temporary camp. And the closer to the gas chambers, the more people were beaten. And yes, one could beat prisoners with a stick, and another one could cut off their ears and genitals, depending on one’s own sadistic needs. But terror itself was a procedure of order and obedience.

- Was it reported to the top authorities? For instance, did anyone know about Franz’s blatant sadism?

- It was no secret to anyone, including the top authorities that he was phenomenally violent, but it wasn’t perceived as something wrong, quite the contrary. First of all, the Jews who were killed were not treated like people. Jews were not people for Nazis. For someone who works in a slaughterhouse, there’s no problem with a pig screeching when it’s killed. Therefore, the Nazis showed no mercy to Jews or to people burned with their villages in Belarus or Russia. And Franz was seen primarily as a high-level employer, as the leader of Treblinka. And his abuses of power were considered to be appropriate, as preventive measures.

From the memoirs of Samuel Willenberg “Surviving Treblinka”:

“The chilly hut filled up with naked women. They stood motionless and terrified, their eyes reflecting nothing but a horrible fear. Suddenly a kind of mist began to rise from the ground; a mysterious halo began to envelop the naked women. The clothing they had just taken off, which still retained the warmth of their bodies, was emitting warm vapors. The women moved towards us and sat on the stools. Some brought their children along. They looked at us in fright as we, the prisoners, began to cut their hair - black, light brown, or totally white. The touch of the scissors caused a glimmer of hope to flicker in their eyes. We knew they imagined that this haircut was a prelude to disinfection; if they were being disinfected, they were to be left alive. They did not know that the Germans needed their hair to make mattresses for submarine crews, since hair repels moisture. After the haircut the SS man opened a door and ordered the women out - onto Death Avenue, the one-way road to the gas chambers. Hundreds of women passed my way that day. Among them was a very lovely one about twenty years old; though our acquaintance lasted only a few minutes, I have not forgotten her. Her name was Ruth Dorfmann, she said, and she had just matriculated. She was well aware of what awaited her, and kept it no secret from me. Her beautiful eyes displayed neither fear nor agony of any kind, only pain and boundless sadness. ‘How long will I have to suffer?’ she asked. ‘Only a few moments,’ I answered. A heavy stone seemed to roll off her heart; tears welled up in our eyes. Franz Suchomil of the SS, the man in charge of sorting gold and dispatching transports to the gas chambers (he was sentenced to six years’ imprisonment in 1965) passed by. We fell silent until he was gone; I continued cutting her long, silken hair. When I had finished, Ruth stood up from the stool and gave me one long, last look, as if saying goodbye to me and to a cruel, merciless world, and set out slowly on her final walk. A few minutes later I heard the racket of the motor which produced the gas and imagined Ruth in the mass of naked bodies, her soul departed”.

- There is an important notion in the book: the information provided by eyewitnesses of the revolt in Treblinka, sometimes not fully correspond to reality for understandable reasons (for instance, unconscious or conscious “enlargement” of whiteness’s role in the event). How should we relate to the memories of Wiernik and Willenberg? Are they reliable? How can one be sure that the details they gave were actually seen with their own eyes?

- These memoirs must be perceived the same way as the testimony of any other prisoner. In general, historical research is not a retelling of documents. “This fact was found in the official document, and therefore is true” – only charlatans or those who consider their audience fools can use this phrase. The historian does not analyze individual documents or evidence, but a complex of sources, taking into account its origin, coherence, historiography. Ideally, the researcher reflects on the methods of analysis, trying to understand what he can or cannot learn. If you meet a document, a certain protocol, which states that more than 4 million prisoners have been killed in Auschwitz, it cannot simply be taken and used as an “official source”. “Official” is the status of a specific document, which does not make its content more reliable than others. Coming back to the book, I would propose our opening article as an example, namely the paragraph on the uprising of 2 August 1943. It was written by Mikhail Edelstein, and in my opinion he was able to juxtapose the various sources, putting at the centre the question of what we could possibly know about this event.

- Were there any stereotypes about Treblinka (both your personal and commonly known) that you were able to disprove through your work on the book?

-I would not call it stereotypes, because the history of the extermination camp is more or less known. I would say that it was possible to clarify many details: functioning of the camp in the first months of its creation, interaction between Treblinka-1 and Treblinka-2, some private cases and myths. For example, documents linked to the same Suchomel, which was always presented as a “good German”, made it clear that it was the other way around. We were able to find out some new details connected to the dynamics of control and internal resistance, though it doesn’t seem to be a fundamental discovery at first glance. The very functioning of this system looks more defined and detailed. Equally, personal tragedies have come to the fore. The details of Treblinka’s relationship with the outside world are also very important - it gives an understanding of the context of the camp’s existence. Goldfarb’s testimony is important from the point of view of the discussions about the number of gas chambers. Yet, Sergei Romanov has quoted him in his works earlier.

From the interrogation report of Abraham Goldfarb, who transported corpses from gas chambers in Treblinka. The Village of Kosów Lacki, 21 September 1944.

«Two wachmanns worked near the engine. The first of them was Ivan, who was called "Ivan the Terrible" in the camp. It was a tall, 27-28 year-old, brunette man. There was a reason why he was nick-named as “Ivan the Terrible”. He was even crueler than Germans. I remember one time, when I was carrying bodies Ivan called one Jew from our group and cut his ear in front of everyone and handed a severed ear to this Jew. An hour later, this Jew was shot dead by him. I remember another case, when he killed one of our workers with a metal bar to the head. When I was transporting corpses from gas chambers to the pit, there was a horrific picture of maimed people. In addition to the gas poisoning in the cells, many had their ears, noses, other part cut off, women had their breasts cut off (…).

As I have already said, my function was to transport the corpses from the “death-bathes” to the pits. 200 - 300 Jewish prisoners were involved in this process. Some of us were busy taking the bodies from the cells to the ramps. Others carried the corpses on the stretcher, throwing them in pits. The number of people killed in the camps is hard to determine. On average, 5,000 people were killed every day. There were days when one thousand people arrived; there were days when their numbers went up to 10,000 or 15,000. Apart from the limited number of people left temporarily for dirty work, all others were killed on the day of arrival”.

- The second point that became clear when working on the book (here I agree with the opinion expressed by Mikhail Edelstein) - on the basis of new sources the whole history of the Operation “Reinhard” in fact, should be rewritten. A study has to be conducted, taking into account all the sources available to scientists.

And the third point is the way the Soviet side worked to investigate crimes, taking into account the differences in views of the ChGK (The Extraordinary State Commission for the Establishment and Investigation of the Atrocities of the German Fascist Invaders and Their Accomplices) and the military (the Prosecutor’s Office and the political authorities). The latter ones in fact wanted the story of Treblinka to be publicly reported, unlike the ChGK leadership. And it improves our understanding of how the ideological machine worked in the USSR.

- A person who will discover such a systematic description of these terrible events for the first time can be deeply shocked. A person may not have the ability to perceive such material, and it is impossible to measure his or her strength in advance. At the same time, your (and now our) task is to have as many people read the book as possible. Can you suggest some sort of safety technique for the readers? How can we warn them and help them deal with this stuff?

- I think it would be advised to start reading this book with Willenberg’s memoirs, as he focuses on resistance practices, rather than on crimes. These memories help to understand that Treblinka was not only about Kurt Franz and his dog Barry and not only about humiliation of all kinds. It was a special world of mutual assistance of prisoners who sought to remain human. Most of the published transcripts were written with help of survivors, who wanted to describe the horrors of Treblinka, to record the evidence in order to then bring the Nazis to justice. Probably they couldn’t say a lot, and, probably, the things that were not of the interest of the investigation became the things of the past. There was no difference between the “search for truth” and the “accusation” in this case. The same is true for many post-war testimonies, especially those said in court. Therefore the memoirs of Willenberg or the memoirs of Glazar* (were published in Russian earlier) are not just a story of abuse and tortures. These are descriptions of the camp’s life in extreme circumstances, but with glimmers of normality. We can see this through friendship and disputes, jokes and songs, discussions and quarrels, mutual aid and assistance, corruption and resistance. Even the story about a masturbating guy is also about preserving normality. Treblinka failed to destroy normality and humanity. And this is a good thing to know.

But, of course, this book is scientific research, so it’s about understanding the past. But we really wanted the book to awaken compaction in our readers, rather than terrify them or make them reflect on the issue. The book has the potential to provide food for further thought on many issues: man and system; guilt and responsibility; emergency and normality. Of course, if we reduce it to slogans, the meaning of our work is lost. And compassion is an important social skill that is lacking in modern Russia.

(*Richard Glazar - Czech Jew, prisoner of Treblinka, one of the survivors of the August 1943 uprising, author of the book “Trap with a Green Fence”).

From Max Levit’s testimony on life in Treblinka and its liquidation [August 1944]

“12-14 year-old boys were also involved in work in “labor” camp. I remember that in March 1942 60 children were brought from Warsaw. Untersturmführer Fritz Preifi, nicknamed “Old” selected 15 who were weak and skinny boys and ordered to kill them immediately as unfit for work. The German who used to live in Odessa, by the name of Svidersky (nicknamed “One-Eyed'') together with other wachmanns took hammers and killed all those boys in front of us. We heard heartbreaking screams of some of the boys, but in general, the children died peacefully, because they must have known long ago that they were going to die. The children only asked to be shot but the wachmanns, primarily Ukrainians, replied: “Jews do not deserve to be shot. We’ll kill you with hammers''. Later, the boys chosen by Fritz Preifi worked in the kitchen, cleaned potatoes, scattered ashes from the stoves where people were burned, grazed cows, and so on. Two boys - Moishe and Polutek, who tried to escape, were hanged by the Germans in front of the other boys. They were hanged by Untersturmführers Lanz, Gagen, Lundecke, Stumpe (nicknamed “Laughing Death”) and Camp Commander von Eupen. The rope which Moishe was hanged on was too long, and the boy could touch the ground with his foot. Lanz, who was a woodman untied the rope from the gallows, pushed the boy to the ground, stepped on his head and pulled the rope. The other boys cried looking at this and said: “Moishe and Polutek are fine, they will not live any more”. Thus, about 15 more boys were murdered by hanging or beating. 30 survivors were shot by the Germans at the time of the camp’s liquidation, as the Red Army was approaching Kosów. All 30 boys led by their leader Leib went to the grave singing Soviet songs "Wide is My Motherland", “My Moscow”, "The Internationale '' and shouted: “Long live Stalin”. They were children of workers from Warsaw, Grodno, Białystok, Brest etc. The day before being killed the boys dug their own grave”.

- I know from my own experience about a strong sense of hopelessness, which the reader eventually faces with. Examples of resistance are inspiring, but still the numbers are not comparable, executioners and indifferent observers are dominant. What can be set against this oppressive knowledge?

- It seems to me that people who read such books possess solid knowledge, and therefore they do not build a picture of the world on the basis of one book. True, the description of suffering of the prisoners can be very depressing. But in the end, there was a rebellion that allowed many to escape. At the same time, the history of Nazi crimes highlights the significance of the Red Army’s exploits. True, the Danish king who wore yellow badges in protest was a hero. Those who managed to survive concentration camps are also heroes. But the Nazi machine could not be destroyed without those who were ready to fight it with rifles in their hands, who could break the Wehrmacht’s spine. It was done by the Allies, with a key role of the Red Army.

Here, again, it’s all about emphasis. If we focus on Treblinka, we get hopelessness. If we focus on the practices of internal resistance, one is tempted to say that only internal resistance could allow someone to survive. But we mustn’t forget that it wouldn’t work without a collective fight against evil.

Now I am concerned about another issue. I had a class with some undergraduate students from one of Moscow’s universities yesterday, and we started talking about Nazi crimes, and here I came across a slightly different perception. Have you heard of the Stanley Milgram obedience experiment, in which electric shocks were administered? The point was that an authority scientist ordered to administer electric shock to another person’s body, and the participants of the experiment did it, even though they hurt others. Of course, there was no electric shock applied during the experiment, so the special actors depicted the pain, but the subjects didn’t know about it. Some of the students understood it as follows: is evil in each of us, let alone the Nazis. That is why Germans, even Suchomel in Treblinka, can’t be considered guilty, as they had to do what they did. They had no choice, and we have to put ourselves in their place and show them… compassion! I was completely shocked by this discussion, although compassion is a central value for me. Then I asked a question that I thought was somewhat confusing: why do you empathize with the “ordinary German” rather than with his victim? And here we face another problem - it’s easier to associate yourself with the killer than with the victim regarding obedience to the system. When we reflect on Suchomel and his attempts to hide his sins behind virtue, we humanize him, while 800 thousand prisoners of Treblinka remain just a “number”, because we know nothing about them. That is why a detailed discussion of the Nazis can have unpredictable consequences if it is not accompanied by an equally thorough discussion on the victims or on those who conquered fascism.

From the memories of Jankiel Wiernik:

“Dear Reader: For your sake alone I continue to hang on to my miserable life, though it has lost all attraction for me. How can I breathe freely and enjoy all that which nature has created?

Time and again I wake up in the middle of the night moaning pitifully. Ghastly nightmares break up the sleep I so badly need. I see thousands of skeletons extending their bony arms towards me, as if begging for mercy and life, but I, drenched with sweat, feel incapable of giving any help. And then I jump up, rub my eyes and actually rejoice over it all being but a dream. My life is embittered, Phantoms of death haunt me, specters of children, little children, nothing but children.

I sacrificed all those nearest and dearest to me. I myself took them to the place of execution. I built their death-chambers for them.

Today I am a homeless old man without a roof over my head, without a family, without any next of kin. I talk to myself. I answer my own questions. I am a nomad. It is with a sense of fear that I pass through human settlements. I have a feeling that all my experiences have become imprinted on my face. Whenever I look at my reflection in a stream or pool of water; awe and surprise twist my face into an ugly grimace. Do I look like a human being? No, decidedly not. Disheveled, untidy; run-down. It seems as if I was carrying a load of several centuries on my shoulders. The load is wearisome, very wearisome, but I must carry it for the time being. I want to and must carry it. I, who saw the doom of three generations, must keep on living for the sake of the future. The world must be told of the infamy of those barbarians, so that centuries and generations to come can execrate them. And, it is I who shall cause it to happen. No imagination, no matter how daring, could possibly conceive of anything like that which I have seen and lived through. Nor could any pen, no matter how facile, describe it properly. I intend to present everything accurately so that the entire world may know what "western culture" was like. I suffered while leading millions of human beings to their doom, so that many millions of human beings might know all about it. That is what I am living for. That is my one aim in life. In peace and solitude, I am constructing my story and am presenting it with faithful accuracy. Peace and solitude are my trusted friends and nothing but the chirping of birds furnishes accompaniment to my meditations and labors. The dear birds. They still love me otherwise they would not chirp away so cheerfully and would not become used to me so easily. I love them as I do all of God's creatures. Maybe the birds will restore my peace of mind. Perhaps I shall some day know how to laugh again.

Perhaps that will come to pass once I have accomplished my work and after the fetters now binding us have fallen away”.