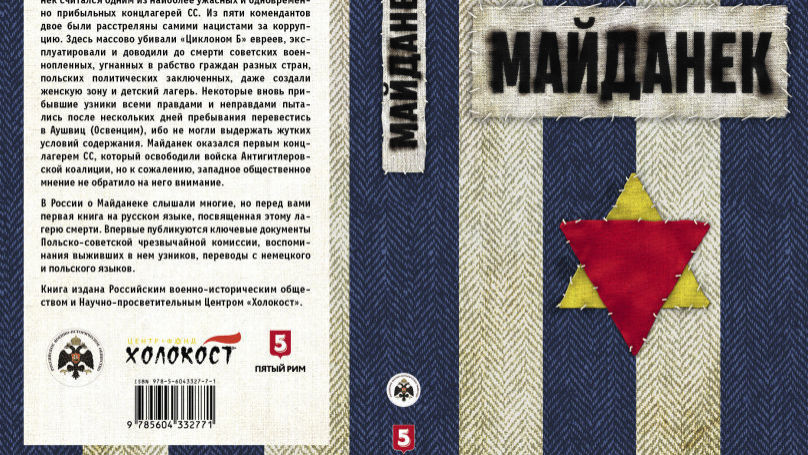

The Russian Military Historical Society (RMHS) along with the Russian Research and the Educational Holocaust Centre have prepared the “Majdanek Concentration camp. Investigations. Documents. Memoirs” historical documentary collection. This is the first edition in Russian to tell the story of the concentration camp, which was liberated by the Allies first and which revealed the shocking reality of the Nazi death factories to the world. The collection includes articles, documents, memoirs and official records, most of which were published for the first time. We had a chance to discuss this unique collection with its editor, Deputy Director of the Department of Science and Education of the RMHS Konstantin Pahaluk. The conversation turned out to be highly informative and we did not consider it possible to reduce it, so we are publishing it in two parts.

- Konstantin Alexandrovich, the book mentions that the SS camp “Lublin” (better known as Majdanek – named after the neighbouring settlement Majdan Tatarski) remains a historical gap for many types of research, despite the fact that the camp is quite famous and even became a symbol of exemplary organized mass extermination, but still, the details and systematized materials about had not been publicly available until recently. Your work is the first one in Russian. What do you think about this tragic paradox?

- First of all, it`s connected with the false fact about the camp`s recognition. Sometimes people think that if something is constantly mentioned it equally becomes well-studied. Despite the active talk about Nazi crimes which we can observe in Russia does not rely on the solid historiography, which has been created only in the last 10-15 years. The second reason is the complexity of working with documents. It is not possible to simply take and retell the reports of Soviet investigative bodies, especially those which were created at “the top” - they were written not so much in the name of truth, but of retribution. We have to deal with a large German collection of documents, as well as eyewitness accounts, which were written in different languages. For example, a Holocaust historian is highly required to know at least Russian, English, German, Yiddish and even French, because these are the key languages the main historiography and memoirs were written in. The third reason is fear. Dealing with such topics is an immersion in history which contains numerous notes which can insult national self-awareness - pages of collaboration, betrayal, behaviour. Going into detail seems to be frightening to many; it is much easier to stay limited with narrow formulas.

- Oswiecim is supposed to meet the same criteria in terms of complexity. Why is it studied significantly better?

- It is better to use the word Auschwitz, because the camp was German, not Polish, so, it is better to use the German version. True, it is bigger than others. This is the most illustrative example, a symbol of the Nazi policy of destruction. It was originally built for Poles, later it started to host Soviet prisoners of war, here the experiments with “Zyklone B” poisoning gas were conducted, and when it proved itself to be effective – it had been applied in one of the Auschwitz` sub-camps until the end of 1944. The total death toll is over 1 million people. Because among other things, Auschwitz was a huge factory of slave labour - with enterprises, manufactures, special equipment for forced labour, etc. When we use the “factory of death” expression, Auschwitz is the prime example. The factory is a well-established mechanism for turning undesired people into corpses, for depriving the rest of the prisoners of everythung human, social and individual, on lowering them to the “naked body” required only for maximizing the economic machine of the SS.

Reference

«Majdanek» - Polish name, «Lublin» - Nazi one. From 1941 to the beginning of 1943 it was a camp for prisoners of war, then it became a concentration camp. It was built by Polish specialists from the civil companies of Lublin.

Two of the five commandants, Karl Otto Koch and Arthur Florstedt, were shot by the Nazis themselves for corruption in April 1945. By the way, Koch became Majdanek’s commandant a month after he ordered to make a lampshade of human skin in Buchenwald.

Several dozen SS-men (in the Commandant) and unions of the Death's Head Division (in the External Guard) served in the camp. The remaining few hundred employees were collaborators, including former prisoners and Lithuanian police battalions.

Majdanek was to become a “slave-owning base” - 150 thousand souls of free labour and 60 thousand SS-men in a special military town.

He was primarily engaged in economic exploitation, but from the spring of 1942 became part of the system of extermination of Jews. The “valid” prisoners were driven through the camp as through a sorting centre, the rest were exterminated. The belongings of the murdered Jews were brought here from other camps. They were sorted and sent to Germany by prisoners.

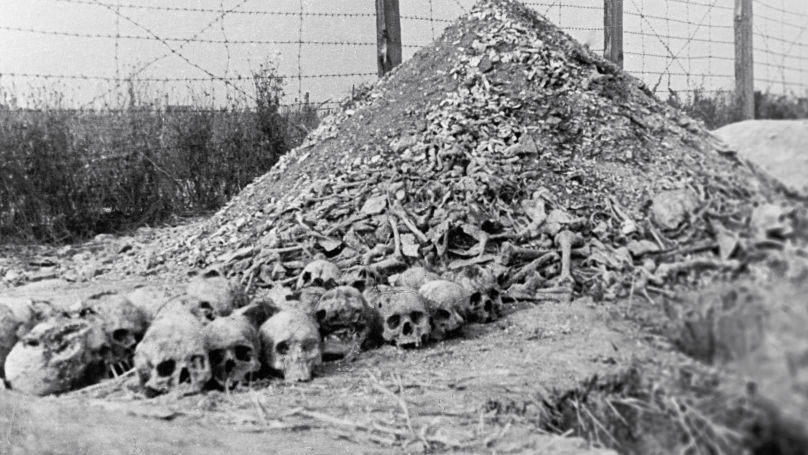

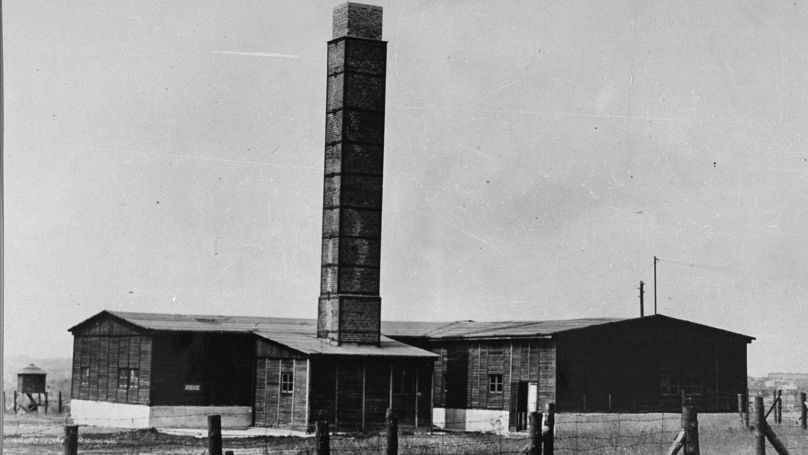

From the autumn of 1942 to the autumn of 1943 Jews were killed in gas chambers of Majdanek, including those who had not been killed in Belzec, Sobibor and Treblinka. About 60,000 - 80,000 people were killed here. The bodies of those shot were burned right in ditches - they burned for days. The crematorium was put into operation after the massacres had stopped. In 1943, Majdanek headed the list of concentration camps by the number of deaths from exhaustion. From 1944 onwards, the invalid prisoners were taken there.

At least 500 escapes took place. On 14 July 1943, 80 Soviet prisoners escaped during the night. Commander Koch shot the rest of the team and reported to his superiors that he had prevented the escape. The truth was soon discovered, and Koch was fired. What happened to the escaped prisoners remains unknown.

According to the Majdanek Museum`s assessment, at least 150,000 prisoners passed through Majdanek. Zinoviy Lukashevich, a historian, counted at least 360,000.

- During the preparation for this conversation, I found a quote: “When we analyzed the history of this camp, it turned out to be forgotten. It was the first camp liberated by the Red Army, numerous Soviet correspondents were there, a special commission for the investigation of crimes was established, but it was practically forgotten by both historians and ordinary people”, - the head of the archive department of the Russian Research and Educational Holocaust Centre Leonid Terushkin said”. What do you think this gap in collective and professional memory can be attributed to?

- This is a very difficult subject, which one can hardly focus on for a long time. As for Majdanek itself, the Poles were primarily held there, so it is well-known in Poland. However, the majority of Majdanek’s victims were Jewish, but the scale was much smaller than in other “specialized” concentration camps. Therefore, when it comes to the Holocaust, Auschwitz (or even Auschwitz - Birkenau) and Treblinka are the first to be remembered. Majdanek is somewhat marginalized in the history of the Holocaust. The same is true of Soviet citizens: not many prisoners of war and internees passed through the camp, so we don't give due attention to Majdanek - there were many other topics that seem more relevant and of primary importance. The specialized research was carried out by the Poles themselves, by the Majdanek Museum. And in general, the history of the camp was written by them in detail. Our book is a supplement that can be made on the basis of domestic documents.

-Is there a broader reason why the history of Majdanek turned out to be obscure?

- Yes. For instance, the objective difficulty of finding a common language that would express the commonality of the suffering of completely different victims who have died due to different Nazi policies of extermination. We can’t borrow it from the West for two reasons. First of all, any actual memory is a conversation about “us” and can be learned from its own past only. Secondly, the experience of Nazi terror in Western Europe was different from the Eastern experience; even today Nazi crimes are reduced to concentration camps and the Holocaust for the general Western European public. In the case of the Soviet Union, the Nazi policy of extermination on its territory is not about concentration camp but a mass execution, Babiy Yar for instance, brutal terror in the guerrilla zones, deliberate starvation of citizens and so on. The Soviet approach was to say that “the Soviet people as a whole were the special victims of the Nazis, we suffered the most”. The desire to emphasize the common suffering of the entire Soviet people, however, has led in practice to the blurring of the understanding that the idea of Nazism was to divide societies into groups and to apply different policy to each group: someone to be destroyed, someone to be resettled, someone to be deprived of rights, etc. Understanding of specific crimes, in order to pay tribute to victims, requires common terminology and analysis; it requires understanding of the motives of criminals, which become invisible under the vail of the notorious “genocide of the Soviet people” conception. But it’s a really important thing to understand, otherwise it is not possible to have a public conversation about specific crimes, a dialogue, which in practice is constantly reduced to the claims “why some people are remembered instead of others?“. In a number of foreign publications one can the following word combination: the Nazi policy on the territory of the USSR was genocidal. I myself, however, support the formulation of “the policy of destruction” as an umbrella concept referring to a whole complex of criminal actions.

I`d like to point out that the conversation “commonality of tragedy '' has not actually taken place from the very beginning, and the intentions were buried by propaganda. Thus, from the war years onwards, propaganda, due to political situation, has deliberately made the Slavs the main victims. That is to say, everyone is equal in suffering, but “Slavs are more equal”. The documents clearly illustrate that Soviet officials as well as many citizens perfectly knew about the consistent extermination of Jews, but again, they tried to cover this fact up. The elimination of people with physical and mental disabilities was also neglected. Thus, the same children of Yeysk - it can be qualified as “a crime against Soviet childhood”, but the Germans killed only people with disabilities there and saw it as the implementation of the “racial hygiene” policy. Accordingly, we are yet to reflect on the various aspects of Nazi crimes and to pay tribute to the various victims and groups of victims, emphasizing their common identity at the same time. I think that the commonality of suffering is emphasized not through common formulas and proverbial equality (which in practice is ensured by the removal of a number of victims from history), but through the ability to see and understand the diversity of crimes, upbringing the empathy to completely different victims, including those who are “other” rather than “own”. Jews, survivors of the Siege of Leningrad, disabled people, prisoners of war, residents of burned villages, gipsies - they are victims of different kinds, but they are very closely related. Of course, if the purpose of remembering crimes is not compassion, but anger and retribution, then such details are unnecessary.

Of course, you can rightly say that the level of suffering of victims can`t be compared. Yes, it's true. “Who had suffered the most” is an unethical question. But that doesn’t change the fact that every crime has an unsub, a perpetrator and a criminal, the Nazi system in our case. It means that we can’t avoid understanding the issue of the motives of this system. And for many people, it turns out to be a big problem: the Nazis did not consider Soviet citizens as a Soviet nation. The Nazis did not consider Soviet citizens as such! They considered them Russians, Belarusians, Ukrainians, Jews, Gypsies etc. Moreover, the ideology portrayed our country as a “Jewish- Bolshevik state”, and Jews were the first victims in occupied territories. It does not mean that “Jews suffered the most”, but it was the Nazis who chose Jews as the main victims.

And the attitude to the Jewish subject, which is fundamental to the understanding of Nazism, became the most vulnerable point of the Soviet discussion about the crimes of the Nazis. That’s why we’ve seen a lot of manipulations when everyone knew that Jews were the first to kill, but the arguments were carefully generalized, something like “everyone was killed”, “Soviet citizens”. This is where the trickery began, there were a lot of uncomfortable topics. Until the '90s, it looked like this: it's impossible to talk about Sobibor, about Pechersky’s feats, without mentioning Jews. Dirty pages of collaborationism, which took place not only in the occupied territories also caused misgivings. For example, in Treblinka, where more than 800,000 Jews were killed in less than a year, the gas chambers were filled with gas by Soviet collaborators. However, the Soviet Union has not been able to supply the gas chambers.

- Under what circumstances did you decide to fill the gap in the Majdanek theme?

- The theme of the Nazi policy of extermination has been with me since 2016. For me, this is related to the important theme of memory - historical memory and its use in politics. Moreover, the feature film ”Sobibor” was released in 2018. The RMHS was involved in this film, initiated or supported a number of projects in the memory of Pechersky. The scientific department decided that this memorial activity should be supplemented by scientific activity as well, and therefore together with the Educational Holocaust Centre, we published a scientific collection (the ”Sobibor: From both sides of barbed wire” collection, 2018 – editor`s note). After that I wanted to continue. I thought that I should do something similar with Majdanek. I went there, under Lublin. I went to the archives. I discovered not only the documents on the investigation of the crimes, but also wonderful memories of the Soviet prisoner of war, doctor Suren Barutchev. They were not completely unknown in Russia or in the Majdanek Museum: a number of researchers knew about their existence, but for various reasons they had not been published. When I found them in the collections of the State Archive of the Russian Federation, I was surprised that such a brilliant source had not been published. They are well-written and were created “while the trail was still hot” - it is an extremely rare case, memories of the concentration camp experience were usually written 10-15 years after. The testimonies recorded immediately after release are also problematic: they were usually told to the investigator, to the prosecutor or to the court, or vice versa, the story of the camp was aimed at bringing the perpetrators to justice. On the contrary, these memories were primarily an act of feelings expression, a desire to tell about his traumatic experience to get some kind of therapeutic effect. It is important for the people who survived the tragedy to speak out, and thanks to Konstantin Simonov Barutchev was able to do it, and an interesting fact is that he did not write them down, but dictated them, which gives double strength to the text.

When we published Barutchev’s memoirs, we added the testimony of Dionys Lenard, a Jew who had escaped from Majdanek. In 1944-45 he disappeared without a trace, but the text about his stay in Majdanek was already distributed in the Slovak underground. It is a well-known source abroad; it is also much-quoted due because it is evidence of the Holocaust itself, written “immediately after”.

Reference:

Dionysus Lenard is a Slovak Jew from Žilina who was sent to Majdanek in April 1942. Around the end of June - the beginning of July of the same year he managed to escape to Slovakia and then moved to Hungary. His post-war traces were lost. He wrote the memoirs in 1942 and gave them to the Slovak Jewish Council, then its copy was quoted by Rabbi Armin Frieder in his diary, and this version was published in Israel in 1961 without due regard to origin or authorship. The original was discovered later. This is the first-ever testimony of a surviving prisoner of Majdanek, written during the war and in the midst of Holocaust politics.

From the memories of Dionysus Lenard:

“Since the gates of the camp closed behind us, all eternal values have ceased to exist. Everything has become instantaneous. And human life lost its meaning. Every day, 400 to 500 people died. Half of them died naturally, unless someone who was tormented to death could be considered a natural death. They were usually elderly people who were unable to live in such conditions and work. Others didn’t die of natural reasons. I didn't see everything, I couldn't be everywhere. I describe only the events I've witnessed myself or heard of. One morning a group of prisoners with many old people arrived. The one who has not seen the wet dirt of Lublin camp does not know what dirt and mud are. After even a little rain, the ground softened so much that it was dangerous to walk on. It required a lot of dexterity to walk on the marshy ground in wooden shoes, when you were ankle deep in dirt (in the original – “by 20 cm''. - editor`s note). One Jew from eastern Slovakia tripped and fell to the ground. At the time of the fall, the old man had accidently touched the SS man’s ankle, who was just passing by. He took out his pistol and shot him on the spot. I've witnessed such cases many times. First corpses were buried, and then they were burned in a crematorium behind the second “field”. An Austrian from Vienna worked there, and he had spent eight years in concentration camps. All his work was burning bodies. It is no wonder that all these events have had a terrible impact on us and have completely paralyzed our nerves. Another old man from Nitra committed suicide: at night he approached barbed wire and ran towards the fence, what was forbidden. He was shot by a convoy. (...)

Two days after the arrival of the Jews from the Lublin Ghetto, thousands of women were brought to the camp. First they were put in the camp, and then they were loaded onto trucks. I happened to see them up close, and I didn’t believe my eyes. One can somehow understand when SS men beat men. Men are stronger, men are more resistant and they can stand the pain more easily. But when you see the SS men beating weak women, hitting them with a rifle butt when they can’t get on the truck... There was a five-year-old girl there, pretty as a picture. Raphael himself couldn’t have painted a more beautiful child. She had blonde, long, curly hair. She fell behind and got stuck in the dirt. She started crying. The innocent child could not expect someone to cause her suffering for no reason. But the SS hit her in the face. If a policeman hadn’t stopped me, I would have finished him off. Then I realized that the Nazis were not human and not beasts, they were demons from the Netherworld, who didn’t belong with our planet”.

Death Camp for Everyone. Part Two

What we can learn from Majdanek and the world that allowed it to happen

This is the second part of our interview with Konstantin Pakhalyuk, editor of the ‘Majdanek Concentration camp: Investigations, Documents, Memoirs’ and Deputy Director of the Department of Science and Education at the Russian Military Historical Society.

How long has it taken you to go from idea to finished product?

The work on the collection took me a year. We wanted the book to be interesting to both general readers and specialists. The idea was that the person who had read it from cover to cover would be able to form a detailed picture of what Majdanek was and how the knowledge about it has developed. As a result, there is an extensive introductory article in which I summarise the contemporary historiography of Majdanek, a lot of documents and then a section devoted to memoir. Incidentally, when we started to collect information, I wanted to find out more information about Suren Barutchev - the Soviet surgeon who was an inmate of Majdanek and who wrote a memoir. Not much information was available but by chance we found his daughter Karina Surenovna when she was congratulated on an anniversary in some corporate journal and consequently I learnt that she was head of a department at one of the medical universities in Saint Petersburg. I wrote to her, and she replied. Later I met with Barutchev’s granddaughter to clarify whose handwriting was in the edits and who made the deletions and insertions and she confirmed that the edits were made by her grandfather. She also gave me a copy of a little book about the history of her family, which she had made with her relations. I’ve learnt a lot about Barutchev and about the context in which he wrote the memoirs thanks to that book. After the collection was published I planned to hold a presentation in Saint Petersburg, but it was impossible because of the coronavirus, and at the end of last year Karina Surenovna died. Barutchev’s fate was truly amazing. And his brother, by the way, was an architect who designed many buildings in Saint Petersburg.

Reference:

Suren Konstantinovich Barutchev was born in 1896 to a wealthy Armenian family in Shusha. After graduating from the Medical Faculty of Kiev University, he treated the wounded in during the First World War, he served on the Caucasian front, was a military doctor in the Red Army, and later he worked in Baku, Azerbaijan, where he became director of a hospital. During the Great Patriotic War he was mobilised, but in April 1942 he was arrested because of a false denunciation and sentenced to 10 years in prison and with his property confiscated. From the camp he wrote a petition to be sent to the front and a year later he was sent to the penalty company, and in the very first battle he was captured while bandaging a wounded soldier. On 2 October 1943, he found himself in Majdanek (his wife was sent her husband’s death certificate), where he was kept for more than nine months before he was released. He later worked as a doctor, but despite rehabilitation in 1956, he was unable to realise his goals fully. On the advice of Konstantin Simonov, whom he met during the war, he wrote his memoirs. The censorship didn't pass it, and Simonov managed to conduct an interview with Barutchev, including some fragments of the memories.

According to the memoirs of Suren Barutchev, a prisoner of war and a doctor:

The most common so-called “joke” played by the SS was the shooting one: the “guilty person” was forced to stand still in front of the barn - a warehouse of dirty laundry - and stay wherever he was told. The SS approached the victim pointing a gun at him and drawing closer until the barrel was almost touching the victim’s forehead. The SS would then shout “Ab!” [Away!] and either fire straight or into the ground. At the same time another SS man came up behind the victim and hit him on the head with a wide board. Since the victim would instinctively close his eyes and the blow from the board came as some sort of impact, the prisoner would usually fall unconscious. If the shock killed the victim, it was declared an act of suicide and it was felt that the joke had failed. However, if the victim came to and tried to open his eyes, the SS then performed a sick dance of savagery, bending over the victim and shouting in his ear: “Oh, hello! You’re on the other side! You see the Germans are here as well! You see that SS men are everywhere!”

There was another “joke” with drowning. In the middle of each field there was an oval-shaped concrete pool of 3.5m by 2m and about 2m deep. There was a main water pump in the centre of the pool. Such pools served to decorate fields and store water for the purpose of irrigation. The joke was that a prisoner was pushed into a pool and had to dive into the water. He was allowed to jump out of the pool, but every time he tried to raise his head out of the water, he was beaten with either the iron heel of SS men’s boots or with a board or a stick. If, after several attempts, the breathless victim managed to jump out of the water, he had to dress in three seconds. If he did not succeed in this, the punishment was considered not served and was repeated. Many of those who were subjected to such a “joke” did not survive. Then the Petty Officer of the third field Birzer drew up the usual certificate claiming “suicide of a prisoner”.

The book took about a year to complete. My trip to Majdanek, in Lublin, Poland, took place in January 2019 and was followed by a search for key sources. The most important source of information on Majdanek in the USSR was the report of the Polish-Soviet Commission on the atrocities in Lublin-Majdanek. It was published in the autumn of 1944 and was freely available. But we have found documents on the organisation of the commission, about the discussions which were taking place, about the attempts to “push Jews aside” and to create an image of “universal” tragedy.

There’s a lot of interesting material - including the document on 3 November 1943, when more than 18,000 Jewish prisoners were killed during an operation called “Harvest Festival''. Polish prisoners recalled that the shootings were carried out accompanied by the waltz ‘Waves of the Danube’.

We also added an article by Zdzisław Łukaszewicz, a Polish historian and judge whose research into exterminations in concentration camps was the first actual scientific work on this topic, where all emotional or ideological feelings were laid aside and instead a balanced analysis was adopted in an attempt to understand what exactly happened. To that end, we added another interesting part - the lists of criminal trials from the archive of film documents. Based on this material, Roman Zhigun wrote an article about the first documentary of Majdanek which is an important additional source about the camp`s history. The most amazing moment is when the camp’s ex-workers were trying to justify themselves and can’t even understand what they are on trial for.

FROM THE SECOND PROTOCOL OF THE COMMUNIQUE OF THE POLISH-SOVIET EXTRAORDINARY COMMISSION FOR INVESTIGATING THE CRIMES COMMITTED BY THE GERMANS IN THE MAJDANEK EXTERMINATION CAMP IN LUBLIN

The crematorium couldn’t burn all the bodies. That is why the Germans organised special fires, for which they dug special pits in which iron frames were installed [the Commission saw iron frames and pits with burnt sides during its visit to Majdanek]. Wooden planks were put on the frames and a layer of corpses were laid on them, then another layer of planks and then corpses, and so on. Such a construction could consume more than 500 corpses; it burned for several days. Witness Zheznik, a Polish Army corporal, worked on the burning of corpses. He confirmed that the crematoriums were insufficient for burning all the bodies of the prisoners the Germans had killed in gas chambers, so the German murderers had to build special fires. Witness Golyan said that the bones that remained after the burning of the bodies were ground in the mill erected for this purpose.

Polish historians – employees of the Maidanek Museum - contributed greatly to the research. Barutchev mentioned the names of many Polish prisoners. I needed to find proof that these people had existed and our Polish colleagues fully supported us in that way. They were really interested in the book.

In general, should it be published in English, it will be of great interest, since many of the documents in our archives are unknown to foreign researchers and those interested in the history of Nazi crimes.

-Have you discovered anything fundamentally new while working on the book?

One thing is fundamentally new - the understanding of how these crimes were investigated immediately after the arrival of the Red Army, and how the first version of the camp’s history was written. And it’s very difficult to write about it in the name of truth - rather than retribution - when faced with extreme violence.

Another important thing is learning about the last months of Majdanek - in other words, although almost all the Jewish prisoners had been exterminated and the camp had done what it was built to do, everyone already realised that Germany had lost. And this is a slightly different story, with very different behaviours – those who saved others, those who collaborated, the Germans. The German doctor, Gett, a prisoner who was perfectly happy to be in Majdanek, had power over prisoners and could send valuable parcels home. Or the SS man who had secretly freed two Polish girls and then was reported by Polish civilian labourers and sent to the front. The story of a concentration camp is not just a story of violence, it’s a story of very different people who came to the camp in different ways and behave differently as well. Some people cooperated, saving each other, others followed the principle “a man is a wolf to another man”. And some prisoners turned out to be much more terrifying than the SS-men themselves, so the difference between the perpetrator and the victim is blurred by the specific reality of the concentration camp. This is what the famous Auschwitz prisoner, the Jewish Italian chemist Primo Levi called the “grey zone”. Barutchev depicted the phenomena perfectly in his memoirs.

Majdanek was a big complex. There were several zones where prisoners of war, political prisoners, women and children were kept. We have been able to find out that the female guards in the women’s zone primarily were young girls in their mid-twenties. The guards in the men’s zone were approximately the same age. Which face do we see when visualising a criminal? This is a young, beautiful face. But this is the face of a criminal who arrived willingly because the pay was better than elsewhere. Another issue is the crimes of Soviet citizens, the prisoners of war who cooperated with the administration willingly, almost with pleasure, and those prisoners of war who became the guards. Barutchev recalled that the Soviet folk-based songs ‘Katyusha’ and ‘Andrewsha’ were often heard from the watchtowers, and who sang them? The collaborators.

-How would you describe the essence of Lublin-Majdanek as being unique among concentration camps?

A lot of things blended together here - inhuman treatment of prisoners of war, Holocaust, the extermination of Jews, political terror in occupied Poland, exploitation of civilian population of the Soviet Union, the inclusiveness - women’s zones, children’s barracks. This camp is an embodiment of what the Nazi extermination policy consists of: common suffering caused by different extermination policies.

-How do you deal with the inevitable occupational burn-out and emotional turmoil? While working on the “Nuremberg. Casus pacis” project, we have been deeply immersed in the topic for several months and sometimes feel as though we are on the verge of a mental breakdown. We search and advise each other on some special techniques. What do you feel in that sense?

I can’t cope with that. I burn out and move on. For instance, I couldn’t finish our next book on Treblinka because I wasn’t able to write an introductory note - the topic is so difficult that I couldn’t physically do it. I have nothing to advise, but... understanding that the common sentiment of surviving prisoners was that they fought for life and opposed the system so that they could live really helps. They were dying but badly wanted to survive because life is important. Resistance in a concentration camp meant preservation of your own identity through prayer, culture, mutual aid, through any meaningful activity and art, whether it be some handmade craft or singing in barracks. What we ordinarily consider simply as culture, assumed an entirely different meaning within the context of the camp - rather than music, literature, art, it becomes an act of resistance and the prisoner’s ability to preserve his or her identity. It served as the basis for further fighting, which in some cases, such as Sobibor and Treblinka, resulted in massive uprisings. True, it was important for the former prisoners, the Holocaust survivors, to tell them what they had been through so that their suffering would not be forgotten. But still, the common thread running through every story is to live on. It is to strive for a normal, peaceful life. Therefore, the memory of Nazi crimes is important to me as the way to affirm the value of a simple, peaceful life.

It’s always been obvious to me that there exists in the human soul an abyss, but the interesting thing is how people get into it, how they get out of it and how they fight it. Mass suffering and mass murders are abnormal. The humiliation of people, cruelty and gradual and total destruction of human identity is abnormal. For me, this topic’s importance is clearly defined: when speaking of Nazi crimes, we first must analyse how individuals face a criminal system but not universally recognised as such. True, there are those who happily take part in the destruction and there are victims, but most people are somewhere in the middle and that’s the most interesting thing.

It gives you the material to reflect on very important issues: first of all, personal responsibility for crimes committed by politicians but on your behalf; how to behave when evil is happening next to you (can the desire to distance yourself from it be seen as collaboration with the criminals?); preservation of your own identity, of personal sovereignty as a way to oppose the system and keep the right to judge right from wrong; propaganda, when vivid pictures create an image of the enemy and justify crimes; when there is no neutral choice and you are either an accomplice in crimes or a victim of a criminal system (I would like to point out that this question concerns not only the Germans but also many Soviet prisoners of war, who were given a choice - starving death or betraying of their country).

These questions are crucial and inevitable while discussing Nazi crimes, you can’t simply fall back on the old “these guys were good - and these were bad”. From such a black or white perspective this theme becomes pointless and even dangerous: describing ourselves as people who have “conquered fascism” does not make us invulnerable to fascism. And perhaps the most important thing is that the history of Nazi crimes is impossible without the memory of the victims and without the ability to sympathise with them. One has to remember that the victims were not always our “friends” (fellow citizens, co-religionists, representatives of one culture or ethnic group etc.), but sometimes our “foes”. The ability to see, feel and share other people's suffering is the most important guarantee against falling into what Germany was in the Thirties.