Every year on 9 May and 22 June numerous disputes about the Second World War erupt. This year’s book, "Stalin’s War" by Sean McMeekin has sparked off new controversies. The 47-year-old American revisionist historian who has in the past written about the First World War, said that by entering into an alliance with the USSR rather than with Nazi Germany the West made a big mistake. Not surprisingly this finding - scandalous even by modern western propaganda standards - has provoked great controversy. In Russia, there was talk of a "new phase of revising the history of the Second World War", and The Sunday Times noted that the idea of a coalition with Hitler "looks more like a computer game scenario than a serious historical assumption". At the request of the "Nuremberg. Casus Pacis" project, Alexey Isaev, a candidate of historical sciences specialising in military history, highlighted the facts which were distorted by McMeekin in his book and deserve attention, explaining why his ideas cannot be taken seriously.

McMeekin’s "childish" mistakes

The general impression of McMeekin’s new book can be described as "agitation and propaganda turned inside out". The author maintained a tense narrative by using as his default setting the old trick of presenting positive assessments to negative and vice versa - in essence, a Topsy-Turvy book. Consequently, in an attempt to shock, the author has made many serious factual mistakes.

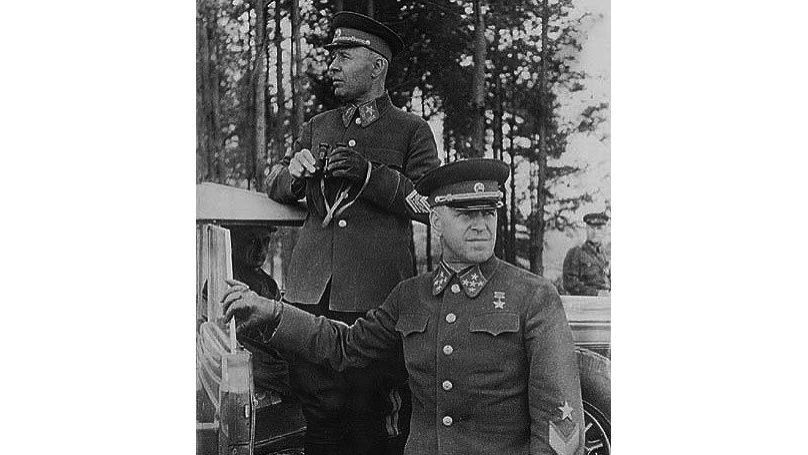

McMeekin demonised the USSR and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in just the way Soviet propaganda had demonised the West. It was done by a similar method of suppressing facts: the author ignored the history behind the 1939 negotiations between the USSR, France and Great Britain and skipped to the event of August 1939 and the military negotiations between the Soviet Union and Germany. Furthermore, McMeekin reported sensational news that France’s Divisional General, Joseph Doumenc, had given the Soviet people`s commissar, Marshal Kliment Voroshilov, a secret map of the "Maginot Line" - a system of French fortifications on the border with Germany. In fact, the military missions of Great Britain, France and the United States during the meeting on 13 August 1939 were presented with inaccurate data on the "Maginot Line", including incorrect information about its extension to the sea. But there is a serious doubt whether it had any influence. The author ignored numerous now-known facts that the West deliberately prolonged negotiations with the Soviet Union (it was the original strategy of Britain and France). McMeekin doesn’t take into account the generally recognised mistakes which had been made by western countries, replacing them with erroneous facts, which will be discussed below.

McMeekin’s writing contains mistakes that range from being at best - by today’s standards - childish, to unacceptable for a historian. For example, he explains the motives behind the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact relying on the “record” of Stalin’s speech at the meeting of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of the Bolsheviks on 19 August 1939, which had never really existed.

It has been proved now that the text of the “speech” was written in Europe and reprinted by French news agency Havas and Le Petit Parisien, a prominent newspaper in France’s capital, in various versions, and Russian archives (for the sake of credibility, McMeekin says that "the text was found in archives") keep the document as a trophy of French origin, captured from the Vichy general staff. The disputes about the events of 19 August 1939 among Russian historians are a thing of the past, and quotations from the made-up text became bad manners.

The myth of offensive plans

Regarding the events just before the outbreak of the Great Patriotic War, McMeekin has repeated all those old canards about Soviet plans. Thus, Stalin’s 5 May 1941 speech to graduates of the military academies in the Kremlin is presented by McMeekin as a radical turn towards an offensive strategy which allegedly drove Semyon Konstantinovich Tymoshenko - the People’s Commissariat of Defense - and Georgy Zhukov, the Chief of the General Staff, to propose a "preventive strike".

However, there was no real radicalisation of plans. Generally, McMeekin avoids unambiguous and odious assessments, referring only to Stalin’s mysterious behaviour during the run-up to the war. On the other hand, he speaks directly of Soviet troops being trained and transferred to the West on a deadline of between 1 and 10 July 1941, "with potentially offensive targets". Although, it was just an author`s hint – it was a very inaccurate one.

Besides, McMeekin claims that the construction of airfields - which had been begun by the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs in the border areas - was an offensive step and resulting from Stalin’s May "offensive" speech. However, modern historians know that the decision to build the airfields had been taken in the winter, and the construction of concrete airstrips for all-year training of pilots actually had a deleterious effect on the Soviet Air Force and reduced its fighting capacity.

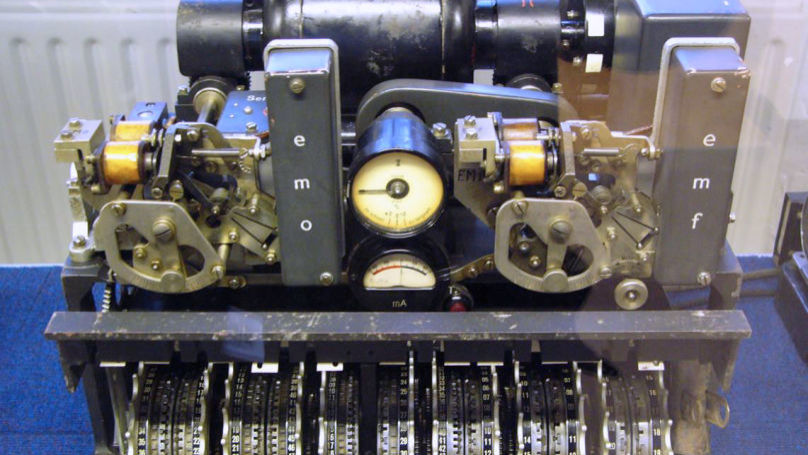

McMeekin claims to have made a number of "discoveries" such as the “fact” that Churchill shared data about Operation “Ultra” (which was a secret, long-term operation of British intelligence by which it was able to decipher German encrypted correspondence – editor`s note).

But in fact there was nothing to share in 1941. Furthermore, the Allies exercised the greatest caution when sharing with the USSR any of the information they’d obtained. Therefore, McMeekin’s claims that Stalin had more significant sources of information in Berlin than "Ultra" is simply not the case. This part of the text is again rather weak and gets into a terrible muddle about operational and mobilisation plans and is full of questionable allegations.

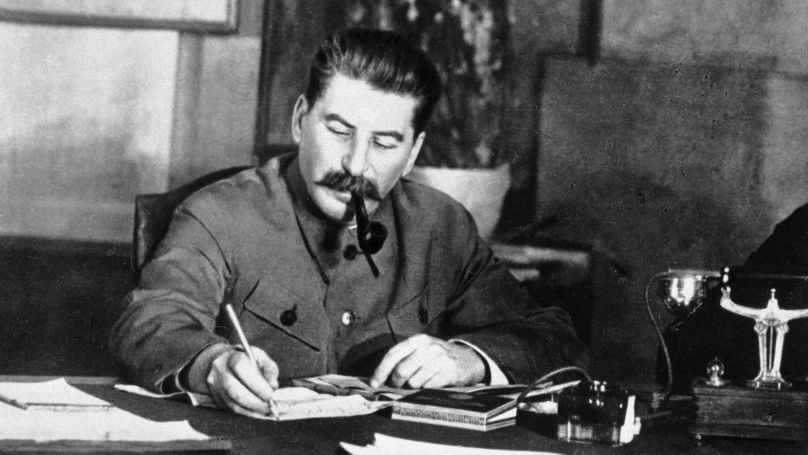

Vozhd (Leader) Stalin

The tale of the clash between Germany and the Soviet Union begins perfectly reasonably, discussing how the inaccuracy of the legend of a frightened and confused Joseph Stalin can be proved by referring to the visitors’ book for Stalin`s cabinet in the Kremlin. The author prefers to call Stalin “Vozhd” (Russian for “Leader”, apparently making a link with the term "Führer").

However, McMeekin then begins a somewhat discombobulated recounting of Mark Solomon’s dubious theory of mass desertion of Soviet soldiers and their commanders in the summer of 1941. McMeekin compares how many troops there are in the districts with the groups of opposing armies which is a futile thing to do without taking into account the Red Army’s pre-emption in deployment. Such practices were uncommon in the First World War - a period McMeekin has studied - but it was a well-established tactic by June 1941.

The author’s explanation for the Allies sending aid to the Soviet Union also seems to be unconvincing as well.

According to the author, the Soviet side is to blame for the shortage of Lend-Lease supplies in 1942, which supposedly had been held up by Murmansk’s insufficient air defence, and the absence of icebreakers in Arkhangelsk, especially in the summer of 1942. The dramatic story of Convoy PQ.17 is briefly described, but who ordered the convoy to separate?

Besides, McMeekin seems to be terrible at numbers: for example, he cites figures for the presence of Lend-Lease equipment in separate brigades in the city of Gorky in the summer of 1942, reporting that T-34 tanks were produced there. For the record, Gorky Factory No 112 produced more than 150 tanks a month, which was considered slow and as a result the factory’s director was replaced.

It would seem logical to tell readers how many Lend-Lease and Soviet tanks were at the front and in the rear at the time and how many foreign vehicles there were. But according to the author, the number is "insignificant". The same goes for figures provided for jeeps or motorcycles which had been delivered in the Soviet Union by the beginning of the Stalingrad battles - about 37,000 trucks and 7,000 jeeps. As of 1 January 1943, the Red Army had 378,800 vehicles and only 5.4 percent were imported under the Lend-Lease scheme.

"Killers in Lend-Lease boots"

When recounting The Battle of Kursk, I was ready to cut McMeekin more slack. Wisely rejecting the Soviet propaganda version that the Battle of Prokhorovka was a crucial moment for the Battle of Kursk, McMeekin predictably and uncritically repeated an equally dull version from the German side out of Erich von Manstein’s memoirs on the impact of the Allied invasion of Sicily and the folding of the offensive operation “Citadel” in Kursk.

True, the SS division "Leibstandarte" was sent to Italy, but it had handed over the equipment to two units of the SS tank corps, which went to the Mius River, to the southern sector of the Soviet-German front. It was the Mius operation, accompanied by the offensive of the western and Bryansk Front, which had begun on 12 July 1943, that stopped the "Citadel" operation. Stephen Newton wrote about this at the beginning of the millennium.

Further descriptions of events were written in the same spirit. Regarding the Warsaw uprising, McMeekin does not even ask the question “how could the poorly armed rebels resist for two months?" The answer is obvious: because the Red Army locked up all other German reserves around Warsaw. But the Soviet reserves themselves were ambushed during the battles of Magnuszew and Puławy, on the Narew, so they could not really help the rebels. In fact, McMeekin has many pro-Polish moments which are often quite absurd.

As a result, "Stalin’s War" reads more like propaganda than history. In fact, the work of American military historian Robert Forczyk on the same topic is much more credible although Forczyk can hardly be accused of sympathising with Stalin. But his sense of professionalism trumped emotion.

In McMeekin’s book, the Red Army - which arrived in Germany and Eastern Europe at the end of the war - was represented as a gang of robbers, murderers and rapists with Lend-Lease equipment and in Lend-Lease boots. This image of soviet soldiers resembles the "brightest examples" of Nazi propaganda of 1944 and 1945.

It’s obvious that modern armies which will consist of more than a million combatants are not peopled entirely with angels. The Allied forces in 1944 and 1945 had serious problems with discipline and fell far short of the ideal in their treatment of local populations. But in fact, poor discipline and crimes were harshly punished.

The same applies to British-American troops and the Red Army. The state policy of both the western Allies and the USSR was entirely at one in that regard.

Was Hitler better than Stalin?

The most interesting question is what does McMeekin offer rather than the scientific version of events? In his concluding section, which bears the eloquent title Stalin’s Empire of Slaves, he speculates on "inconvenient issues" including the British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s refusal to conduct peaceful explorations of German positions in October 1939 and June 1940, as well as President Franklin Roosevelt`s rejection of the negotiations in 1943. These steps have been declared the main mistakes of the British and American leaders. McMeekin claimed that rapprochement with Hitler could result in a post-war treaty for Europe that was better than the one achieved in 1945.

The author has also come up with the same sort of ideas while considering the Far East: the Japanese-US conflict could have been resolved by negotiation and thus the creation of communist China could have been avoided.

McMeekin entirely ignores the fact that Japan and China had already been at war in 1941, and China received aid from both the Soviet Union and the United States, the first Einsatzgruppen already operated in Europe in 1939 and 1940 and, by 1943, the "final solution of the Jewish issue" was ongoing.

McMeekin lives in a strange world of delusion regarding Germany and its politics. The Second World War was very different from the First World War which, according to the bibliography, the author has researched extensively. The policy of genocide in the conquered territories was a specific feature of the Second World War, requiring adequate evaluation.

Overall, Sean McMeekin’s book can be described as a step backwards in world history whose incompetence is made all the more glaring when compared with the much more professional and credible studies of the Soviet-German front which have been written by modern western historians.

Alexey Isaev