An exhibition titled “No measure, no name, no comparison” has opened at the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre in Moscow.

The exposition tells a story that many are still not ready to hear – about the genocide of civilians on the territory of the USSR during World War II. There are disputes about the term itself – was it genocide or was it “just” about the cruelty of Hitler’s army in Eastern Europe and the economic interests of the Reich that intended to colonise and enslave the peoples of the USSR? The creators of the exhibition bring us closer to the war era through objects, symbols, and images, sometimes offering the ability to literally enter an occupied space that has been disfigured by Nazism. Natalia Osipova, project manager of “Nuremberg: Casus Pacis”, speaks about the exhibition.

The title of the exhibition is a line from the textbook poem “The February Diary” by Olga Bergholz. It immediately immerses you in one of the key subjects: the Siege of Leningrad. The exhibition also talks about the countless Russian villages burned by the Nazis; about peasants, whose world was forever destroyed by the war. About cities and townspeople whose fates were shattered by the war. About concentration camps and their victims. Places of crime – and components of crime. Perpetrators and their victims. The exhibition shows the opposites: it confronts the viewer with the certainty of the crime in its cruellest form. And you are forced to choose a side.

The exhibition includes unique photos. One of the symbols of the exposition is a photo of Murmansk after a raid, depicting only the chimneys that are left of the city. This is our point of view. There is also the opposite one. German amateur photographers among the active officers and soldiers loved to take pictures, capturing executions and punitive operations.

The invaders often carried such photos with them along with photographs of their wives and children. The daily routine of evil, violence as a background for posing and smiling – these photos strongly resemble hunting pictures with trophies. A collection of the suffering of "the natives" that Wehrmacht soldiers could boast to friends and family. In one of these photos, a team of punishers poses, smiling, against the background of a flaming hut.

“We found a large block of new photographs in the Central Archives of the Ministry of Defence of the Russian Federation”, Andrei Nazarov, curator of the exhibition from the Russian Military Historical Society says. “In the second half of the war, especially when the Soviet forces were advancing, our units had the opportunity to chronicle the events, took a huge number of photographs, and filed them into photo albums. These are the most valuable things. And some of them are represented here”.

The creators of the exposition – the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre, the Military Historical Society, the Military Medical Museum, the State Memorial Museum of Leningrad Defence and Siege, and the State Museum of Contemporary Russian History – have built the exhibition as an emotional journey from one point of grief to another.

A burned-out hut, its dampness and dust, with real household items – the building abandoned by people became the symbol of the vanished Russian Soviet civilisation. These poor huts experienced the brunt of the Nazis. Entering the house, you can feel what it was like to be in the occupied territory and decide where to go: join the partisans or flee as a refugee? Or stay at your place and wait for a sad fate? What will happen then? Will they take us to Germany, or are we going to be shot, burned, or hanged? In this segment of the exhibition, you hear bursts of gunfire from the speakers - and you instinctively duck.

“We wanted to create an emotional backdrop because this is the only way to convey documentary information”, Maria Hades, curator of the exhibition of the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre says. “But we did not build the exhibition on horrors only, we followed an imaginative path. We created the image of a country house. There is little information inside the house itself – apart from household items there is nothing special there. But the feeling of being lost, the sense of the loss of this world is fully present. And the effect of authenticity – there are genuine old objects that were brought from different places. Development Artist Maria Utrobina works in theatre and cinema a lot, and the same is important for exhibition architecture – creating an environment”.

The creators made a space that all at the same time resembles a wooden shed, a barrack, a concentration camp, a heating carriage – images of the cruel 20th century that turned a person into cattle, into a reservoir for fresh blood, into useful meat, from which both fabric and fertiliser can be made.

In the middle of the boardwalk there is a children's coffin on a sled, a symbol of the Siege of Leningrad from a poem by Bergholz:

“Skids are creaking all around the Nevsky

On a children's narrow, funny sled

They drag water in saucepans and buckets

Along with firewood, they carry those who are dead”

The history of the blockade is shown through several items. Scales, a slice of bread, advertisements reproducing the original ones: "Trading my sapphire gold ring and silver cigarette case for food", “Boiling water for the population is for sale”. A teddy bear that outlived its owner: an illustration of the famous museum paradox that things prove to be stronger and more invulnerable than people. This irony finds its darkest manifestation here. The owner of the toy was a child who died during the blockade. Another item is the sandals of a Leningrad girl named Nadia Lavrentieva, bought for her one-year birthday, to be used for her first steps. Although the girl could not learn to walk on time because of starvation, she did so by the time she was four.

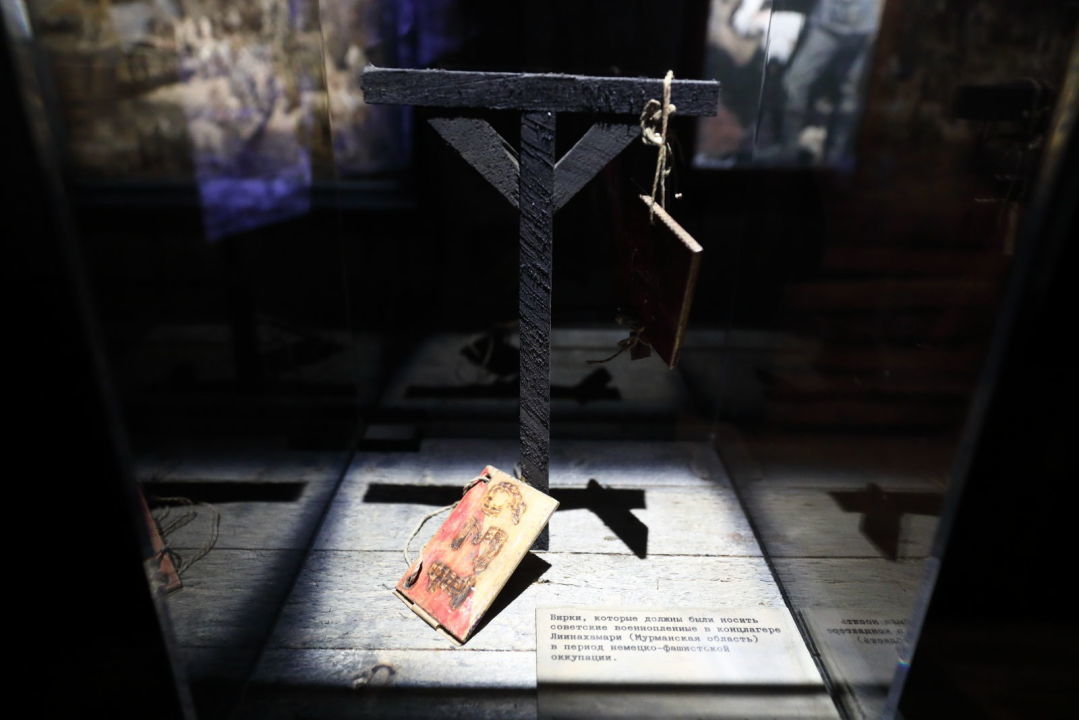

A third point of grief is the exposition dedicated to the concentration camps. The creators elaborate on the numerous types of camps. There are not many items there, but they are symbolic: a sailor suit and the knee socks of a child who died at Majdanek, a prisoner's robe, a badge that a prisoner was forced to wear, and a piece of hair. There are also three paintings by Geliy Korzhev, serving as a triptych instead of icons in this place of sorrow.

An exhibition about murdering people and civilians always evokes the feeling of an impasse: how and why did it happen, and what can be done? It's hard to look at, it hurts too much. But one can overcome the pain if there is a way out to the light. But here there is no way out. There is no light – only from the dim camp lamps. No escape, no salvation, no explanation for what happened, no immunity, no confidence that Nazism is gone forever.

The curators say that even for them, for those who are professionally immersed in the topic, working on the materials for the exhibition was a challenge.

Our understanding of the Nazi crimes is incomplete, we perceive them in fragments: a crime has been committed, it has been investigated, proven, the perpetrators have been convicted, some have disappeared. But in reality, there were no separate crimes. “It was a river of fire and blood that flowed for 3-4 years. The worst thing was the absolute systematic extermination of the civilian population”, Andrei Nazarov, curator of the exhibition, says. He warns that sometimes he can cry while talking about the exhibition.