A brilliant business journalist, Walther Funk became useful to the Nazis in two ways at once. He supervised the German press and contributed to its subjugation, then was responsible for the economy of the Third Reich, the defeat of the Jews' rights and the confiscation of their property, even after their deaths. But the end of his career was inglorious: Funk lost his former influence and drank himself to death.

Businessman

Walther Emanuel Funk was born into a merchant family on 18 August 1890 near Trakehnen in East Prussia (now the village of Yasnaya Polyana in the Kaliningrad Region). His great-uncle was German pianist and composer Alfred Reisenauer, a favourite pupil of the Hungarian composer Franz Liszt.

In 1908, Funk studied law, economics, literature, and music at the universities of Leipzig and Berlin. He received his doctorate in law in 1912. Later, he worked as a journalist for various newspapers, including the Berliner National-Zeitung and the Leipziger Neuesten Nachrichten.

In 1915, during World War I, Walther was drafted into the army but was released from service a year later because of bladder problems.

In 1916, Funk became the editor of the trade section at the Berliner Börsen-Zeitung (Berlin Stock Exchange), and from 1921 to 1930 was its editor-in-chief. He soon became one of Germany's leading business journalists: he published articles in numerous specialised magazines, acted as an expert on economic issues, and presented papers at international congresses and business conferences.

In 1919, Funk married Luise Schmidt-Sieben, the daughter of an entrepreneur. By this time, if he is to be believed, he was already quite adept at communicating with the opposite sex. “My illnesses began when I caught syphilis at the age of thirteen. It was in a beer hall in East Prussia. There, schoolchildren, and I was among them, made love to waitresses in the back rooms for money”, he explained to the prison doctor at Nuremberg. As military interpreter Margarita Nerucheva noted that Funk loved to tell the wardens about his victories over women. He often recalled Berlin's brothels and revelries of dubious repute, accompanied by obscene songs:

“And what great feasts I've had!”, he recalled and his thick greasy lips stretched into a smug smile. “We had the best wines, top-notch champagne, everything just the best. And it really was an unforgettable night out! I ate and drank a lot, as always. And, of course, there were lots of girls. They were the best too. Naked dancers..."

He came to the attention of financial circles in 1920 with an article analysing the role of banks in shaping financial publications. And when Funk's pamphlet on monetary reform was published in 1923, the Reich Association of German Industry presented his work to Finance Minister Hans Luther and Reichsbank President Hjalmar Schacht.

With the support of business and government leaders, in 1927 he became chairman of the press office of the Berlin Exchange Society and the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Berlin, and from 1928 to 1930 was a leading member of the board of the “Society for German Industrial and Social Policy”. At the same time, he developed close links with a lobby group from the Ruhr region consisting of twelve major industrialists, the so-called Ruhrlade.

Führer's Adviser

In the spring of 1931, Funk met Adolf Hitler, who he later recalled made a profound impression on him. Hitler assured Funk that if the Nazis came to power they would not implement a populist economic programme based on the ideas of Gottfried Feder, one of the founders of the NSDAP and an ardent critic of capitalism. Feder’s idea envisaged nationalising industrial trusts, confiscating land for public use without compensation, taking large shops from their owners and renting them out at low prices to small producers, punishing usury and speculation with the death penalty, and finally prohibiting living on an unearned income. The Führer suggested that Funk himself should form an alternative economic policy.

On 1 June 1931, Funk joined the Nazi Party and rose swiftly through the ranks thanks to his contacts with capital and industry. As early as May, he became editor of the Nazi publication Political Economy Service, and in July, on the recommendation of Hjalmar Schacht, Hitler appointed Funk as his personal economic adviser.

“Defendant Funk, soon after he joined the [Nazi] Party, began to operate as one of the Nazi inner circles”, the US assistant counsel Bernard Meltzer, who presented the American case against defendant Funk, said at the Nuremberg Trials. “Moreover, as a Party economic theorist during its critical days in 1932, he made a significant contribution to its drive for mass support by drafting its economic slogans”.

Thanks to Schacht and Funk, the National Socialists turned from socialism, which threatened the interests of big German industrialists, to capitalism. The class struggle, the Hitlerites argued, had been invented by the Jew Karl Marx, and in a nation-state, there could be no unresolvable contradictions between owners and wage-earners who worked together in the same business. And of course, there was no need for trade unions in such a just society; later the German Labour Front, led by Robert Ley, would be set up in their place, uniting both workers and employers.

It was through Funk that the Ruhrlade corporations transferred millions of Reichsmarks to the NSDAP. It was he who ensured the Nazis' contacts with such major industrialists as Emil Kirdorf, Fritz Thyssen, Albert Vögler, and Friedrich Flick. These individuals not only sponsored the Nazi Party but also pressured German President Paul von Hindenburg to appoint Hitler Reich Chancellor until they succeeded.

“He promoted the accession to power of the Nazi conspirators and the consolidation of their control over Germany set forth in Count One of the Indictment; he promoted the preparations for war set forth in Count One of the Indictment; he participated in the military and economic planning and preparation of the Nazi conspirators for wars of aggression and wars in violation of international treaties, agreements, and assurances set forth in Counts One and Two of the Indictment; and he authorised, directed, and participated in the War Crimes set forth in Count Three of the Indictment and the Crimes against Humanity set forth in Count Four of the Indictment, including more particularly crimes against persons and property in connection with the economic exploitation of occupied territories”, the leading US prosecutor Sidney Alderman listed Funk's crimes as he read out the indictment at Nuremberg.

Chief Press Officer of the Third Reich

In February 1933, shortly after the Nazis came to power, Hitler appointed Funk his aide. In March 1933, he became State Secretary of the new Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda. The head of the ministry, Joseph Goebbels, was not enthusiastic about the decision but the respectable business journalist was apparently meant to counterbalance the figure of the minister himself whom President von Hindenburg regarded with suspicion. Funk was in charge of Divisions I and IV within the ministry – the Administrative and Legal Department, and Department for the National and Foreign Press, respectively. He also enjoyed the status of press secretary to the German government and commented on Hitler's actions for the media.

“Funk was the soul of the ministry, and without him, Goebbels could not have built it up. Goebbels once stated to me that Funk was his 'most efficient man’”, in testimony read out at the Nuremberg trials, Max Amann, who held the position of Reich leader of the press and president of the Reich Press Chamber, revealed. “Funk exercised comprehensive control over all of the means of communication in Germany; over the press, the theatre, radio, and music. As press chief of the government and later as undersecretary of the ministry, Funk held daily meetings with the Führer and a daily press conference in the course of which he issued the directives governing the materials to be published by the German press”.

There were some opposite characterisations as well. “Our new chief Funk was an individual who seemed very strange among the traditional bureaucracy. He was a drunken journalist. He had worked at the Berliner Berliner Börsen-Zeitung at one time, but was dismissed a few years ago for laziness”, former ministry official Wolfgang Gans zu Putlitz recalled. “Funk had a stout belly; from beneath his puffy eyelids, his glassy, watery eyes peered out at those around him. The clipped, often unrelated words gurgled from his drooling mouth bore the indelible mark of a dialect typical of the outlying districts of East Prussia. Hindenburg, to whom Funk now reported daily, soon gave him the nickname 'My Thoroughbred Trakehner’ (a sports breed of horse in Trakehnen – ed. note). Funk was incapable of regular, diligent work”.

On 15 November 1933, Funk was elected vice president of the Reich Chamber of Culture (Goebbels himself became president) in addition to his previous posts. This peculiar union united all artists in the Third Reich and strictly controlled their activities. No German could work as a writer, painter, musician, actor, or journalist if they were unaffiliated with the chamber..

From Embezzling the Living to Robbing the Dead

Funk's career in Hitler's Germany was not limited to propaganda. In November 1937, Minister of Economics Hjalmar Schacht, the architect of the Third Reich’s financial system, resigned over a disagreement with Hitler. In January 1938, Funk was appointed his successor as Reichsminister of Economics and at the same time became General Plenipotentiary for Economics. Less than a year later, he replaced Schacht as President of the Reichsbank. And in August 1939, Funk was appointed by Hitler to the six-person Council of Ministers for Defence of the Reich where he was in charge of military and economic affairs.

At the Nuremberg Trials, Funk would defend himself that he did not exercise any initiative of his own and only followed direct orders from Hitler and “Nazi No. 2” Hermann Göring: “I had to do what Göring said”. But compulsion alone does not explain the orders Funk was giving.

He played a key role in pushing Jews out of the economic life of the Third Reich and expropriating their property (it should be noted that Hjalmar Schacht resisted state anti-Semitism in every possible way). Funk’s Third Regulation under the Reich Citizenship Law of 14 June 1938 and the Decree Regarding the Registration of Jewish Property of 6 July 1938 nullified the economic activities of German Jews.

“The state and the economy constitute a unity. They must be directed according to the same principles. The best proof thereof has been rendered by the most recent development of the Jewish problem in Germany”, Funk stated in the Frankfurter Zeitung on 17 November 1938. “One cannot exclude the Jews from political life, and at the same time let them live and work in the economic sphere”.

“On the 3rd of December 1938 he signed a decree which imposed additional and drastic economic disabilities upon the Jews and subjected their property to confiscation and forced liquidation”, Bernard Meltzer emphasised. “Defendant Funk himself has admitted and deplored his responsibility for the economic persecution of the Jews”.

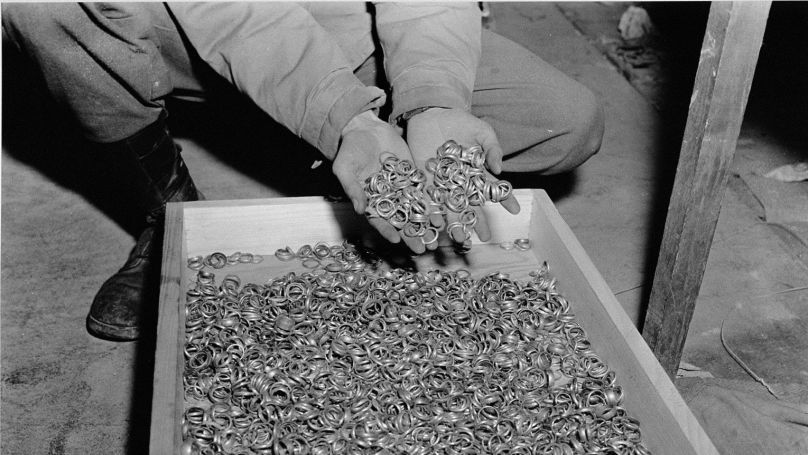

On 9 August 1940, German Jews found that they could not only not earn money but also not spend it – Funk denied them access to bank accounts. And in 1942, the embezzlement of the living was supplemented by robbing the dead. The chief banker of the Third Reich struck a secret agreement with SS-Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler that the valuables of Jews murdered in the death camps should not be returned to their relatives but sent to the Reichsbank. The bank took possession of the coins and banknotes, and sent the jewellery, watches, and other personal items to Berlin's municipal pawnshops, reimbursing the SS for the “costs” of shipping and delivery.

“As Minister of Economics Funk accelerated the pace of rearmament, and as Reichsbank president banked for the SS the gold teeth fillings of concentration camp victims-probably the most ghoulish collateral in banking history”, chief American prosecutor Justice Robert Jackson noted in his closing statement.

Nazi-Style European Union

“It is plain then that defendant Funk exercised comprehensive authority over large areas of the German economy whose proper organisation and direction were critical to effective war preparation. The once-powerful military machine which rested on the foundation of thorough economic preparation was a tribute to the contribution which defendant Funk had made to Nazi aggression”, Bernard Meltzer argued.

After the outbreak of World War II, Funk got his hands on the economy of the occupied states - first Poland, then Scandinavia, the Benelux countries, and northern France. On 25 July 1940, he delivered a keynote speech on the “economic reorganisation of Europe”.

The Funk Plan, as journalists dubbed it, was drafted with the participation of Gustav Schlotterer, State Secretary at the Ministry of Economics, and envisaged Germany's economic dominance in Europe. European currencies were no longer fixed to the gold standard, the exchange rate was rigidly fixed, customs barriers between states were removed and the Ruhr area was united with northern France and the Benelux countries into a “single economic space”. The minister sincerely hoped that such methods would bring prosperity not only to the “Great German economy” but also to the occupied countries.

Hitler assessed the plan and awarded the Reichsminister of economics the War Merit Cross Second Class in the winter of 1942.

From Mobilisation to Collapse

But they soon had to tighten their belts. On 4 February 1943, Funk closed down all industrial, commercial, and catering establishments that had no military significance. This was essentially an acknowledgement that things were not going well at the front. So far, Germany, unlike the Soviet Union, had not put the entire economy on a war footing, so the home front continued to live a more or less normal life. Military defeats made one forget about the comfort of the past.

In September 1943, Funk became a member of the central planning staff of the Ministry of Armaments and War Production. However, starting in 1944, when the Soviets moved in to liberate Eastern Europe, he increasingly lost influence. Reichsminister of Armaments and War Production Albert Speer was openly dissatisfied with Funk, who was unable to cope with both economic and political tasks. The once ambitious minister of economics, who was already fond of a drink, went on a binge and watched in silence as the situation spiralled out of control.

His condition is eloquently illustrated by the story of how the Swedish actress Zarah Leander, who was working in Germany, tried to bring home antique furniture and works of art, but was unable to obtain permission for a long time. Leander decided to cajole Funk, who was head of the relevant commission, and invited him to her Berlin villa.

“When Funk raised his champagne glass to make a toast, Leander asked him whether Mr Minister drinks this feminine drink”, says the biographer of the actress, Anna Maria Sigmund. “I actually prefer stronger drinks. Schnapps, for example, or vodka”, replied Funk. "Wonderful. So do I", said the actress and suggested that the minister compete with her to see who can out-drink who. Funk, who had heard about the star's drinking talents but did not believe it, agreed. It was half-jokingly agreed that the loser would do the winner's bidding. The Nazi minister, with an empty stomach, only managed half a litre of vodka. Leander, who quite professionally snacked on sardines in oil, especially saved for the occasion, won. The next day she was already sitting in Funk's office with the customs papers and politely but firmly asked him to sign them. The minister, who was feeling horrendous after drinking the previous day, silently signed them.

Later, Funk would have to pay dearly for his earlier escapades. His frayed nerves would make him intolerant to noise and bright lights, Funk would be forced to resort to morphine and cocaine injections and take large doses of sleeping pills in the hope of conquering his chronic insomnia and anxiety.

Although Hitler had reserved the post of Reichsminister of economics for Funk in his political will of 29 April 1945, the chair under him had already burned down. The new Reichspresident Karl Dönitz realised that there was no civilian economy left in a country occupied by the Soviets and the Western Allies. On 1 May 1945, Speer became Minister of Economics, and Funk retired.

In June 1945, he was arrested by the British military in the Ruhr area, and in November he was brought before the Nuremberg Trials.

“It is clear, then, that defendant Funk participated in every phase of the conspirators' programme, from their seizure of power to their final defeat. Throughout he worked effectively, if sometimes more quietly than others, on behalf of the Nazi programme, a programme which from the very beginning he knew contemplated the use of ruthless terror and force within Germany and, if necessary, outside of Germany. He bears, we submit, a special, a direct, and a heavy responsibility for the commission of Crimes against Humanity, Crimes against Peace, and War Crimes“, Bernard Meltzer concluded.

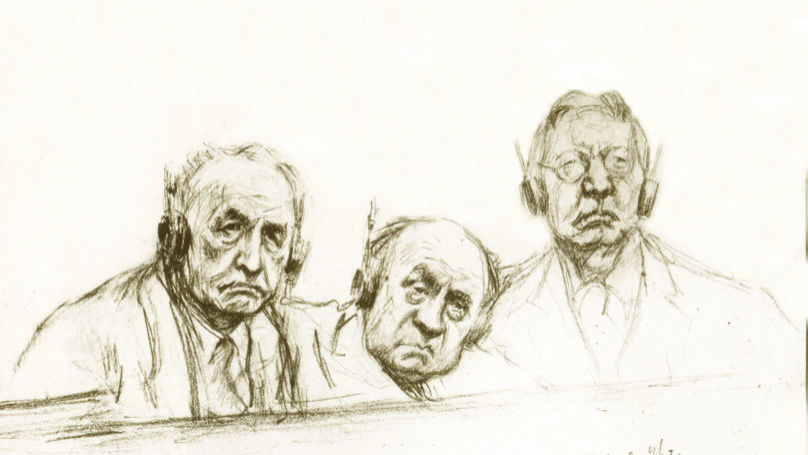

Yet, Funk used every means to justify his own innocence: "I have never in my life consciously done anything which could contribute to such an indictment. If I have been made guilty of the acts which stand in the indictment, through error or ignorance, then my guilt is a human tragedy and not a crime ". And when they showed a film from the concentration camps in the courtroom, he burst into tears and declared that he "did not have the slightest idea about the shower-bags on wheels or about other atrocities". And he was probably the only one of the defendants who kept repeating that he was ashamed, unbearably ashamed.

“But what I wanted to tell you was that there is really none of us — not a single one — who escapes a moral guilt in this matter. I have already told you how my conscience bothered me when I signed those laws for the Aryanisation of Jewish property. Whether that makes me legally guilty or not, is another matter. But it makes me morally guilty, there is no doubt about that. I should have listened to my wife at that time. She said we would be better off dropping the whole minister business and moving to a small three-room flat, than to be involved in such a disgraceful business… Maybe if we had all gotten together and refused to go any further, we might have prevented this final disgrace. Every one of us has this moral guilt. I don't see how the court can acquit a single one of us”.

Sources:

Constantine Zalessky, “Who Is Who in the Third Reich”, Bibliographic dictionary

Olga Fedyanina, “The Fate of A Nazi Man”

Gustave Mark Gilbert, “The Nuremberg Diary”

Wolfgang Gans Herr zu Putlitz, “Unterwegs nach Deutschland. Erinnerungen eines ehemaligen Diplomaten”, 1967

Margarita Nerucheva, “Forty Years of Solitude: Notes of War Interpreter”

Anna Maria Sigmund, “Women of the Third Reich”, 1998

Nuremberg Trials Stenograph, Volumes I, IV, Translated from English by Sergey Miroshnichenko

Ernst Hanfstaengl, “Zwischen Weißem und Braunem Haus. Memoiren eines politischen Außenseiters”, 1970

Walther Funk — Beamte nationalsozialistischer Reichsministerien // Beamte nationalsozialistischer Reichsministerien

Thomas Sandkühler, “Europa und der Nationalsozialismus: Ideologie, Währungspolitik, Massengewalt”, 2012

Christopher Kopper, “Bankiers unterm Hakenkreuz”, 2005

Heinz Handler, “Vom Bancor zum Euro. Und weiter zum Intor?” (From Bancor to Euro: And Intor Next?), 2008

Dieter Suhr, Hugo Godschalk, “Optimale Liquidität: Eine liquiditätstheoretische Analyse und ein kreditwirtschaftliches Wettbewerbskonzept”

Harold James, “International Monetary Cooperation Since Bretton Woods”, 1996

By Daniil Sidorov