The dream of Hitler’s minion to adapt his memoirs to the movie screen did not come true, but he eventually got his 97 minutes of fame

The director of “Speer Goes to Hollywood” (2020) claims that the genre of the film is a historical documentary. The critical opinion ranges from “world sensation” to “masterful fiction” and “manipulation”. How did the “good Nazi” Albert Speer escape execution by shifting the blame on Fritz Sauckel? Why did he talk about himself to a 25-year-old screenwriter for 45 hours? How did he convince the Oscar-winning director to take on the film adaptation of his memoirs? And most importantly: was it all true? Darya Mitina, a social activist and film critic, talks about it.

Israeli journalist and director Vanessa Lapa positions her film as a feature documentary. Seven years ago she produced The Decent One (2014), a film based on a study of SS Chief Heinrich Himmler's personal diaries. Lapa's new film manipulatively titled “Speer Goes to Hollywood” (of course, Hitler's favourite Albert Speer has never been to Hollywood, but the film is simply about the failed adaptation of his memoirs) continues the line of unveiling the true face and role of Nazi criminals. It would seem that history has long since dotted the I's, but indeed some of them got less than they deserved, some got away with it, while others, like Speer, successfully monetised their biographies and spent the rest of their lives enjoying sweet meals, sleeping soundly and dying in the arms of a young mistress in a luxury hotel.

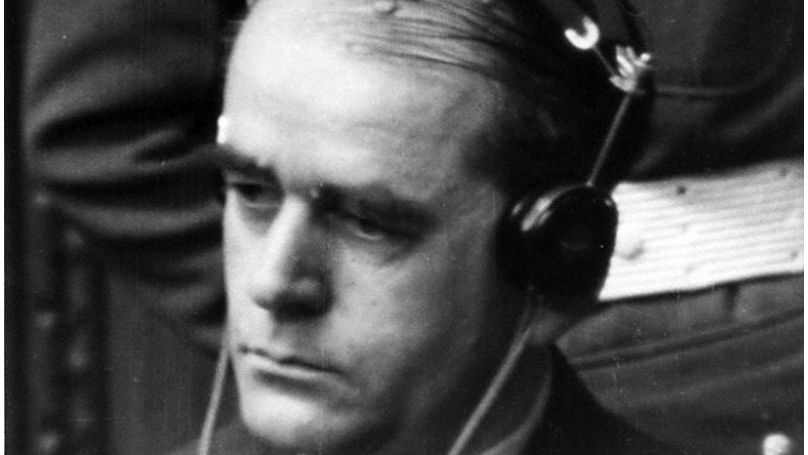

At first glance, Lapa takes a scrupulous approach to the sources – the film turned out to be largely based on fundamental work with archives scattered around the world, lavishly illustrated with footage from the Nuremberg Trials, where the cunning Speer managed to get off the hook and whitewash himself – getting 20 years in prison instead of the gallows, which considering his record is considered the same as an acquittal. We have all seen the documentary footage of the Nuremberg Trials many times, but Lapa turns the hero's line at an interesting angle, essentially reducing the whole story to an absentee “contest” between Speer and Sauckel over who would be able to shift the blame onto the other. Racing against the time and unable to examine all the evidence, the Tribunal relied on the confessions of the defendants, and while Speer spoke of the collective guilt of the Nazi leadership and lied that he knew nothing of the Nazi atrocities, Sauckel, an uneducated redneck and a boot, actually took all the blame for creating the death camps and using the labour of 12 million slaves on himself.

Lapa focuses our attention on Speer's reaction to his sentence – not just a sigh of relief, but a winner’s attitude, filled with prideful superiority towards Sauckel, who would be hanged.

Lapa's work is heavily criticised for the manic, detailed and proving account of the true role of Speer, who was personally responsible for creating not only a system of forced labour but also an enormous slaughter machine – they say that all this is long known and adds nothing new to the subject. I will not join this chorus of critics – I believe that you cannot go overboard on a subject like this, and the more revelations about Nazism are made, the better. There is something else that is unsettling.

The main storyline is Speer’s unrealised dream to film his memoirs “Inside the Third Reich”, for which he recruited screenwriter Andrew Birkin, assuring him that Warner Bros. Pictures and Paramount were already vying for the honour of taking on such a film adaptation. In 1971, Birkin, Stanley Kubrick's protégé, was staying at Speer's villa in Heidelberg and they recorded 45 hours of discussions on the scenario. Vanessa Lapa shows us scratched, grainy tapes of these conversations, where both the elderly, handsome Speer and the 25-year-old Birkin are easily identifiable. But it is not the image that raises questions but the dubbing – we hear not the original voices but the dialogues read out by actors that immediately raises doubts – were there any original recordings of the conversations preserved at all? Do we hear real dialogues, or are they the product of the director's imagination? Is it right, proclaiming a commitment to maximum documentary authenticity, to go so far as to “adopt” such material for the convenience of the viewer?

Apart from the details of the future blockbuster, the former high-ranking Nazi and his interlocutor, who initially doubted the morality of such a project at all, discussed responsibility for crimes - in his usual cynicism, Speer cited Voltaire, Goethe and even André Malraux (“To understand what the outside of an aquarium looks like, it’s better not to be a fish”. - about his alleged ignorance) as justification, saying that he was not a killer but simply an efficient manager: “I was, as in Sophocles' Oedipus Rex, unaware that I was committing crimes”.

At the same time, quite understanding the insignificance of such a position, he voiced a wish to Birkin: “We need a picture, not a photograph”, in other words, not historical truth but a ceremonial portrait in the interests of the client.

Another conundrum is the off-screen story that Birkin persuaded Oscar-winning director Carol Reed to direct the film, but Reed hesitated and refused (saying, "Aren't you planning to wash the black dog white?"), but director Lapa provides no documentary evidence of such negotiations, offering to take her at her word by default. But Birkin and Speer's allegedly credible dialogue about Paramount's refusal to shoot is presented by Lapa as a documentary (Birkin: “Paramount and its Jewish crew refused, accusing you of whitewashing yourself”, –Speer: “That is their perception and their problem. I will always be able to say that it is a feature film”).

One can long speculate about the credibility of such dialogues and the appropriateness of Jew Birkin's joking about the Jewishness of the Paramount studio workers, or one can just fact-check and find out that no negotiations with Carol Reed took place, but with Costa-Gavras, who by that time was already world-famous.

Moreover, meticulous film critic Mikhail Trofimenkov dug up last year's indignant article by Birkin himself on a fringe Trotskyist website, where he refutes all his “dialogues” with Speer included in the film from beginning to end – the tapes have long since become demagnetised, and no Lapa could know what they really talked about. Instead of a documentary dialogue, we are dealing with fantasies of what it might have been like.

Therefore, the proclaimed principle of credibility and punctuality of the facts is not observed by Lapa herself, and for the zealots of historical documentary filmmaking, this is of crucial importance. But for the vast majority of viewers, who are not concerned with Speer's millions of dollars from publishing books or his failed Hollywood fame but rather with his role in the fate of Europe in the last century, Vanessa Lapa's “Speer Goes to Hollywood” is another vivid and macabre illustration of the history of Nazism and its consequences.