The editors' team of the “Nuremberg: Casus Pacis” project – together with the Eksmo publishing house – is publishing excerpts from Philipp Gut’s book about Benjamin Ferencz, the man who organised the trial against the SS punitive special units, introduced the word “genocide,” and stood at the origin of the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

Benjamin Berell Ferencz is a legend in the world of international law. The name of this American lawyer has long been inscribed in history: he was a member of the group of prosecutors at the Nuremberg Trials, investigated Nazi war crimes and initiated one of the twelve “Subsequent Nuremberg Trials,” and later participated in the creation of the International Criminal Court and the establishment of international law. Ferencz is still alive now aged 101.

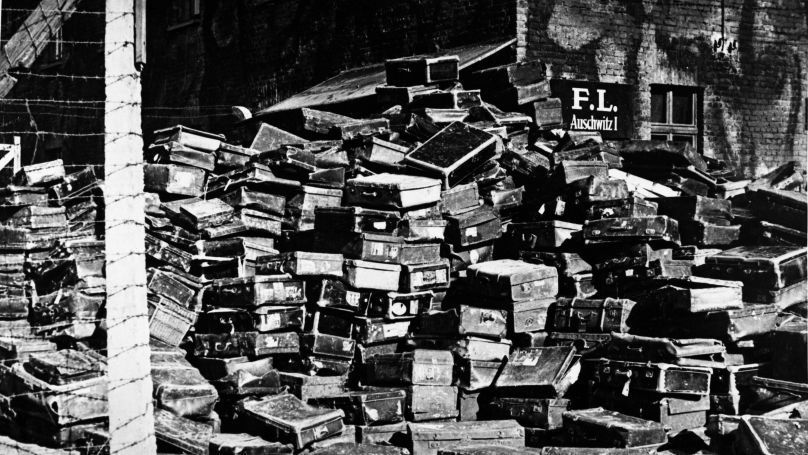

He was born on 11 March 1920 in Transylvania, which then belonged to Hungary before being passed into Romanian jurisdiction a few months later. His parents and their ten-month-old son soon immigrated to the United States, seeking first and foremost to escape the persecution of Hungarian Jews by the Romanians. They settled in New York, lived very poorly, but from an early age, Ferencz displayed outstanding intellectual qualities. He first went to City College of New York, where he studied criminal law and then obtained a scholarship to Harvard. There he was assigned to do research for a professor who was working on a book on war crimes at the time. After graduating from Harvard in 1943, Ferencz joined the army and fought in an anti-aircraft artillery division. In 1945, he was assigned to General Patton's headquarters – his team collected evidence of Nazi war crimes. Ferencz visited concentration camps liberated by the US Army and was also involved in the search for artworks stolen by the Nazis.

After demobilising as a sergeant, military lawyer Ferencz was almost immediately recruited as a prosecutor in the subsequent Nuremberg Trials and worked for the legal team of senior prosecutor Telford Taylor.

This is where his moment of glory came: he discovered detailed accounts of the murders of Jews, Roma, and the mentally disabled committed by the Einsatzgruppen, the special punitive teams of the SS. These reports were kept and carefully archived by the Nazis themselves. Shocked by the discovery, Ferencz went to great lengths to insist during a separate trial for the 3,000 leaders and perpetrators of the extermination of the “Untermenschen” (“subhumans,” a Nazi term for non-Aryan “inferior people”).

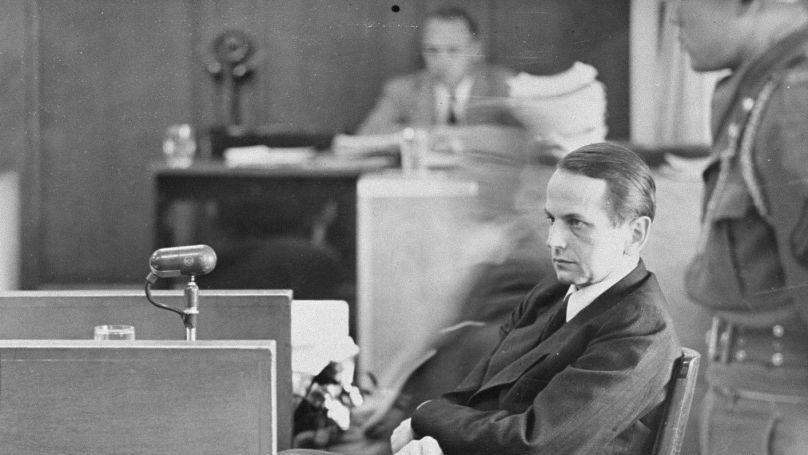

In 1947, Taylor appointed 27-year-old Ferencz as the chief prosecutor, and the youngest in Nuremberg, in the Einsatzgruppen Trial, officially called “The United States of America vs. Otto Ohlendorf, et al.” – the largest mass murder case, which Ferencz conducted entirely on his own from 29 September 1947 to 10 April 1948. He later ironically referred to himself as a prosecutor with a 100 percent success rate, as he won his biggest criminal case ever, the first and only one in his career. The defendants, senior SS officers, were charged with the systematic extermination of over one million people, mostly in the occupied territories of the USSR. All 22 defendants pleaded not guilty, insisting that they had been soldiers and had obeyed orders. However, all 22 were convicted, of whom 14 were sentenced to death, but ten were eventually commuted to imprisonment and only four were hanged. These were the last executions carried out on German soil, which later became the Federal Republic of Germany.

In a 2005 interview with The Washington Post, Ferencz explained how the rules of military law differed at the time:

“Someone who was not there could never really grasp how unreal the situation was... I once saw DPs [displaced persons] beat an SS man and then strap him to the steel gurney of a crematorium. They slid him in the oven, turned on the heat and took him back out. Beat him again, and put him back in until he was burnt alive. I did nothing to stop it. I suppose I could have brandished my weapon or shot in the air, but I was not inclined to do so. Does that make me an accomplice to murder? You know how I got witness statements? I'd go into a village where, say, an American pilot had parachuted and been beaten to death and line everyone one up against the wall. Then I'd say, ‘Anyone who lies will be shot on the spot’. It never occurred to me that statements taken under duress would be invalid”.

After the Nuremberg Trials, Ferencz and his wife remained in Germany for a long time. He was actively involved in the establishment and implementation of a compensation programme for victims of the Nazis, the determination of UN aggression and the negotiations which led to the 1952 Reparations Agreement between Israel and West Germany and, in 1953, the first German law on the restitution of Jewish property confiscated by the Nazis.

In 1956, Ferencz and his family (by that time he had four children) returned to the US and took up a private legal practice, becoming a partner of the ever-legendary Telford Taylor. While pursuing claims of Jewish forced labourers against the Flick Concern, Ferencz observed the “interesting phenomenon of history and psychology that very frequently the criminal comes to see himself as the victim.”

Meanwhile, memories of the appalling revelations during the Nuremberg Trials did not let him go, and Ferencz eventually left private practice to concentrate entirely on establishing the International Criminal Court in The Hague as the ultimate authority on crimes against humanity and war crimes. He wrote several books on the subject, became a UN expert and taught international criminal law. As a matter of fact, it was Ferencz who coined the term “genocide.”

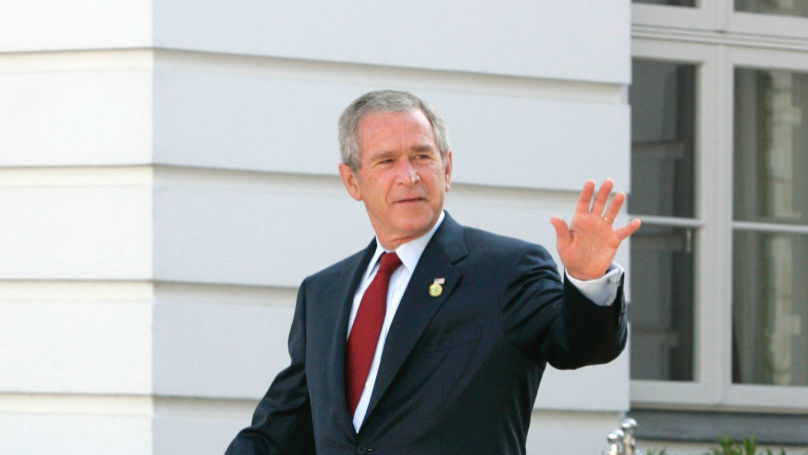

On 1 July 2002, the International Criminal Court was established upon the enactment of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. However, the US – represented by the administration of George W. Bush – objected to the potential opportunity for American citizens to be brought before this court, despite Ben Ferencz’s numerous pleas that the law should apply equally to all. For example, in 2006, he argued that after the war in Iraq, not only Saddam Hussein but also George Bush should be tried because he launched military action without UN Security Council sanction.

Brave Ferencz reaffirmed this view in 2013, reiterating that the use of armed forces to achieve a political goal should be condemned as an international crime and consequently Bush should be tried “on 269 war crimes charges.”

Furthermore, in 2011, immediately following the news of Osama bin Laden's death, Ferencz published an open letter in The New York Times, arguing that “the illegal and unwarranted execution – even of suspected mass murderers – undermines democracy.” The same year, he presented a closing statement in the trial of Congolese militant leader Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, the first defendant to be convicted by the International Criminal Court in The Hague.

In 2009, Ferenc was awarded the Erasmus Prize for notable contributions to European culture, society and the social sciences. In 2017, the municipality of The Hague announced the naming of the footpath next to the Peace Palace in honour of Benjamin Ferencz. Thus, the Benjamin Ferenczpad (Benjamin Ferencz path) was created, and he was presented with a corresponding street sign in Washington.

In 2018, Ferencz was the subject of a documentary on his life, “Prosecuting Evil” by director Barry Avrich, which was made available on Netflix. In the same year, Ferencz was also interviewed for the 2018 Michael Moore documentary Fahrenheit 11/9. He has had several books written about him, and sculptor Yaacov Heller has sculpted a bust of Ferencz in memory of a long, difficult and eminently dignified life dedicated to the fight against genocide. Ferencz bequeathed an enormous personal archive to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington.

Today, the editors team of the “Nuremberg: Casus Pacis” project launches a series of publications of Philipp Gut’s book “Witness of the Century: Ben Ferencz, Chief Prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials and Passionate Fighter for Justice”. We would like to express our gratitude to Eksmo Publishers for their cooperation and providing the materials.

CHAPTER 5. THE PROCESS.

Sensational Discovery: ‘Reports on the Events in the USSR’

The breakthrough came at the turn of 1946-1947, when an agitated Frederic Burin, a talented young investigator, burst into Ben's Berlin office and reported a sensational discovery. In a pile of files from the offices of the defeated Reich, he found folders with many secret reports.

Under the seemingly innocuous title “Reports on the Events in the USSR”, they bore witness to the murderous activities of the Einsatzgruppen, the SS Special Forces, an organisation under the leadership of Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler.

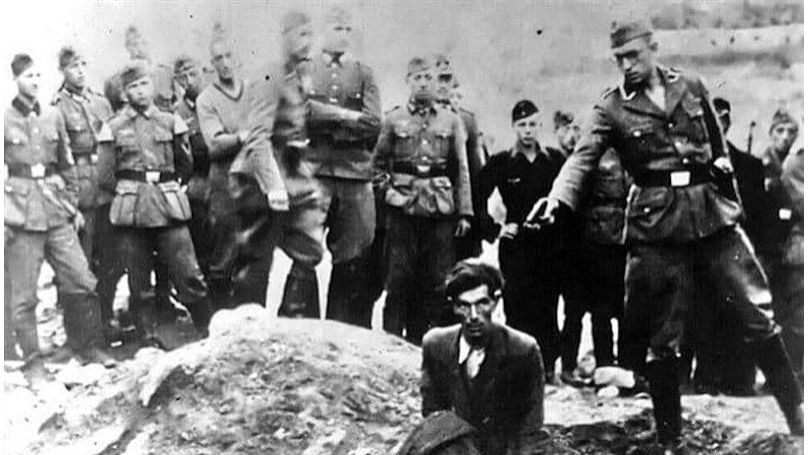

The mobile elite troops were under Reinhard Heydrich's Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) but also worked closely with the Wehrmacht (After Heydrich’s death in 1942 as a result of an assassination attempt in Prague, the RSHA became directly subordinate to Himmler. Kaltenbrunner was later appointed as its head. The assassination attempt on Heydrich, organised by the Czech Resistance with the support of the British secret services, became the pretext for acts of retaliation, including the destruction of the village of Lidice – ed. note). Divided into four groups of around 500-800 men each, they operated throughout the territory of the Soviet Union conquered by the Germans, from the Baltic States (Einsatzgruppe A) to the Black Sea (Einsatzgruppe D). They were to provide “political security” in the rear of the front but their secret mission was to kill all those whom the Nazis considered their ideological enemies: above all Jews and Communist functionaries, but also Roma, the mentally disabled and other “inferior people”. The reports found were sent regularly from the first day of Operation Barbarossa on 22 June 1941 onwards, covering a period of almost two years.

The distinctive feature meant that the perpetrators themselves counted and recorded how many people they had killed.

Since May 1942, the reports have been coming in a modified form under the title “Reports from the Occupied Eastern Territories”.

Ben held his breath. He immediately realised that the papers his team had discovered in the ruins of the former Reich capital were invaluable both for the history and for the investigation. The reports were precise and detailed, including the locations of the crimes, the number of victims, which units carried out the murders, and the identity of the commanders. Ben immediately realised that he had got his hands on a "chronicle of mass murders". Having “reports on the events” was crucial to the criminal investigation because tensions were rising between the United States and the Stalinist Soviet Union, and it was difficult to obtain incriminating documents from the Soviet Union. Ben had once already tried to conduct a trial with the Soviet military administration. The Russians initially showed interest and then abruptly refused. The pressure on Ferencz's team, looking for evidence of crimes among the surviving National Socialist documents in Berlin, increased. Now, the documents were on his desk.

At first, Ben thought the Einsatzgruppen reports were found at Gestapo headquarters. But Burin, who arrived from Switzerland, said that the reports were stored in the archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. These were twelve binders with rotaprinted copies of the original reports. The Reich Security Main Office sent copies to individual high-ranking administrative units, mainly within the SS bureaucracy, but also outside it. The papers uncovered were effectively a complete set of such duplicates, and the only preserved ones. Canadian historian Hilary Earl, author of the first monograph “The Nuremberg SS-Einsatzgruppen Trial, 1945-1958: Atrocity, Law, and History” (2010), confirmed Ben’s first impression and speaks of an “information goldmine” whose significance for the history of National Socialism cannot be overstated. In 2011 alone, all the reports were published in a three-volume document collection by a research group led by Klaus-Michael Mallmann and Martin Cüppers from the University of Stuttgart. A total of 195 daily “Reports on Events” and 55 weekly “Reports from the Occupied Eastern Territories” took up almost 4,500 typewritten pages. The RSHA compiled sets of reports which the Einsatzgruppen Command received from the units and passed on to the central leadership in Berlin.

Reports about the executions were included as if they were about completely unremarkable events.

Apparently, along with political, economic, cultural or ethnological observations, they were something to take for granted.

A representative example is “Report on the Events in the USSR No. 89” from 20 September 1941, which, like all these documents, had a standardised structure. The sender was “Chief of the Security Police of the SD”. Under the date and place (Berlin) with the stamp "Top Secret", it was noted in detail the total number of reports (48) and which of them were among the copies (36). The report was divided into three chapters: "Political Overview", "Reports from Task Forces and their Commanders" and "Military Developments". Observations about the “pronounced musical countryside culture” in Ukraine alternated with the following phrases: “The areas of command activity are cleared of Jews. From 19.08 to 25.09, 8,890 Jews and Communists were executed. The total number is 17315. The Jewish problem is currently being solved in Nikolaev and Kherson”. This information referred to Einsatzgruppe D.

Even the bloodiest massacres were reported in a dry administrative language. In the "Report on the Events in the USSR No. 106" from 7 October 1941 under the heading “Executions and Other Measures” the infamous site of mass execution in Babi Yar was reported: “In collaboration with the [Einsatz]Group Staff and two commando units of Police Regiment South, Sonderkommando 4a [Einsatzgruppe C] executed 33,771 Jews on September 29 and 30. The operation went ‘flawlessly’: ‘No incidents took place’. ‘Resettlement measures’ taken against the Jews were welcomed by the local population. The fact the Jews were in fact liquidated is barely known and, ‘judging by current perceptions, has not met with strong condemnation’. The Wehrmacht also ‘commended the measures taken’”.

The publishers wrote of the outstanding historical significance of the “Reports on the Events”, which made the extermination of the Jews a central element of German policy in Europe, “as the practice of the massacres at Babi Yar facilitated the transition to genocide, which at that time was not yet a clear reference point in Nazi policy”. During Operation Barbarossa it can be established that the grounds for the executions became less and less important, indicating that the extermination of peoples gradually became routine for the perpetrators.

Based on the testimony of the SS officers involved in the events, the Nuremberg Indictment assumed that there was a "Führer’s order" for the mass extermination of Jews and Communists. Even historians have long held this view, despite the lack of a corresponding source. Recent research has called this fact into question. Scholars are inclined to believe that the Einsatzgruppen and their units had more freedom. The logic of the systematic killings was shaped equally by the reality of the Eastern Front and the vague hints and camouflaged terminology used by the Nazi leadership with regard to handling the Jews. And the SS men of the Einsatzkommando, acting in this direction, were implementing these attitudes most radically, filled with a zealous desire to put into practice what their superiors had hinted at. However, the fact remains that the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question” was one of the primary goals of National Socialist policy. And the Einsatzgruppen played a key role in this.

Ben was the first to feel this when he studied the shocking documents in the Berlin office. He noted the areas that were reported to be "free of Jews" and got a general idea of the enormous scale of the criminal acts. “I started counting the number of people killed using a small arithmometer. When I reached one million, I stopped counting”.