The editors' team of the "Nuremberg: Casus Pacis" project, together with the Russian Military Historical Society (RVIO), continues the publication of excerpts from the book "Treblinka: Investigations. Memories. Documents", compiled by the RVIO and the Centre for Holocaust Research and Education (CHRE). Our team brings to our readers' attention two more chapters from the introduction article on the history of Treblinka, written by historians Konstantin Pakhalyuk and Mikhail Edelstein.

From Ghetto to Gas Chamber: Terror and False Hope

The SS did everything to ensure that the whole process of extermination was carried out in secrecy. Realising that information would leak out anyway, they put up signs of one sort or another that would allow the doomed to maintain their illusions. By skillfully combining terror and false hope, the Nazis organised methodical deportations, while accusing the Jews of being the victims of their own slaughter. The deportations usually began with round-ups and violence, but at the same time, people were told that they were going to live in labour settlements in Ukraine.

While Polish and Soviet Jews were transported in goods wagons, deportees from Western Europe were transported in comfortable trains with tickets in their hands. Whether people were aware of their fate is a complex question. For example, as early as 23 July 1942, the day the first train from the Warsaw Ghetto arrived, Adam Czerniakow, the head of the Warsaw Ghetto Jewish Council (Judenrat), committed suicide. He was well aware of what "evacuation to the east" meant, and therefore chose to end his life rather than assist the Nazis in the extermination of his people.

Rumours of what was going on in Treblinka soon enough reached Warsaw. To check these rumours, a teenage boy, Zalman Friedrich, on the orders of the Bund, followed one of the trains in August: he got to Sokołów Podlaski, where he learned from the railway workers that the track there bifurcated and one branch line led to Treblinka. Watching the trains carrying the deportees, Zalman noticed that they came back empty, with no food deliveries made. Soon he bumped into two Jews in the market square who had escaped from Treblinka; they confirmed his worst fears. Rumours later circulated in Warsaw that Jews were made into soap and fertiliser. Regular deportations to Treblinka activated the underground of the Warsaw Ghetto and led to the emergence of those structures which later, in April 1943, initiated an uprising.

In its preparations, reference was also made to what was going on at that extermination centre. Thus, in January 1943, the underground Jewish Fighting Organisation issued a proclamation that called for an uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto. It began with a statement that in Treblinka, 300,000 Jews had been murdered in six months. Similarly, rumours about this place of extermination were spreading in other ghettos, especially in those that were close by. For example, historian Martin Dean says that because of such rumours, as early as September 1942, when the ghetto was liquidated in Stoczek Węgrów, many of the ghetto's inhabitants hid and escaped death. Being transported in overcrowded goods wagons was a real ordeal. Heat, cramming, impossibility to even sit down, stale air, thirst - these were typical descriptions of what happened. The soldiers escorting the trains could shoot at the wagons for no reason, let alone shoot anyone who tried to stick their necks out or squeeze through a tiny window with barbed wire.

Not many survived the way to Treblinka, and the will of those arriving was often crushed. There were also some wild stories. For example, Genia Marciniakuvna recounted the story of a Jewess, Czesia, from Warsaw:

"They never got any water for three days. They defecated there, in the wagon. Children were dying. One dead child had to be thrown out of the wagon after special permission from the Germans. Because of the lack of water, Czesia was in such a state of frenzy that she bit through her blood vessel and drank her own blood".

Sometimes they tried to send children for water: they could squeeze through a small window in the wagons. A. Goldfarb, who arrived on a train from Menjice to Treblinka on 18 August 1942, testified that one boy managed to get water, but was shot during the second ride. For the train crews, usually Poles, it was also no secret whom they were transporting and for what purpose.

A train driver, Henryk Gawkowski, recalled in an interview with Claude Lanzmann that one could hear the screams of people, which made a depressing impression; hence, the Germans gave the train drivers vodka as a bonus. The testimony of railway workers L. Pujava and Franciszek Ząbecki vividly demonstrated that the deportations did not go smoothly.

Some, especially at first, were under an illusion and even tried to ask the Poles where either the town or the colony of Treblinka was. Later on, however, the Jews from Poland generally knew what awaited them, while those deported from Western Europe were in the dark. According to L. Pujava, "those from other countries, it was obvious that they didn't know what awaited them. You could even see one family occupying the wagon. This was, however, very rare; the Germans were achieving a certain goal in this way: allowing them to take away with them more things, which were later taken away in the camp".

Those who realised what awaited them tried to escape by breaking out the windows and boards of the wagon, jumping out while on the move. Some stories of attempts at mass escapes from the trains have also survived. One of them was recounted by Franciszek Ząbecki:

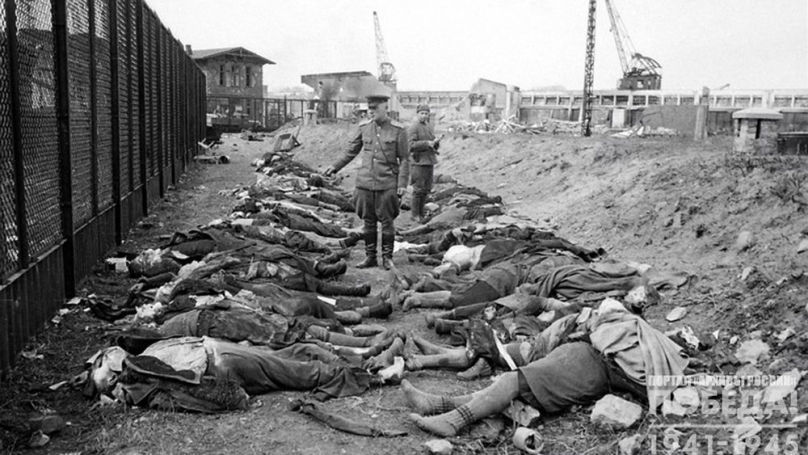

"In August or September 1942, an echelon of incoming people arrived at Treblinka station. It arrived in the evening, and the camp did not receive this train until the next morning. During the night, the prisoners in several wagons broke the wires that covered the windows of the wagons and tried to escape, but the drunken Wachmänner guards opened fire and killed many of them. All the tracks of the station railway were clogged with dead bodies. The next day it took three platforms to haul away these corpses".

Another resident, K. Skarzynski, told of an attempted mass escape from a train carrying Jews from the occupied territories of the USSR in July 1943: "Heart-rending cries of 'Water!' could be heard from all the wagons. The villagers tried to hand over the water but the Wachmänner opened fire. At that time, the people in the wagons - men, women and children - started breaking the walls of the wagons and jumping out of the train.

The Wachmänner unleashed a dreadful shooting spree on the defenceless, thirsty people. 100 people were killed that day. Four corpses of children, who died of suffocation, were thrown out of the wagons, because there were no traces of gunshot wounds. In our village, the local population of Vulka buried all 100 Jews who were murdered. I also took part in the funerals”. Those who managed to escape as the echelon was on its way could only survive with the support of the local population, while Polish peasants often handed over the escaped Jews to the Polish police or the Germans. Of course, upon arrival at the camp many of the doomed, especially Polish Jews, had already given up their illusions.

As A. Bomba recalled, "Some in the crowd realised what was happening, had a premonition that they would not be left alive. They were backing away, refusing to go further – they already knew where they were being taken, what was behind those big gates. There were tears, screams, cries. Words cannot describe what was happening there... Their cries and pleas were in my ears day and night, and stuck in my head". Samuel Reisman, who arrived in Treblinka at the end of September 1942, later testified that just the first sight of it left no hope: "Already then the situation was clear to all of us. The piles of personal belongings near the barracks, the unceasing hum of the excavator, the heavy, deadly smell emanating from another part of the camp, all spoke with sufficient conviction of one thing: we were about to die".

"Each of us had only one wish: to die as quickly as possible".

However, the need to maintain order forced the Nazis to continue to resort to a mixture of brutality and illusion, the latter being sufficient for those who wished to be deceived. Jews who met the doomed were forbidden to talk about the camp's final destination, and their presence instilled hope for a relatively safe outcome. As previously noted, the "infirmary" and the Jews who served it were marked with Red Cross signs. The Nazis could also show certain civility to those deported from Western Europe. Gradually, a set of imitations was expanded to give false hope. When undressing, money and jewellery were offered to be deposited in a special treasury.

Y. C. Domb, deported at the end of September, recalled that "in the middle of the court there was a well, and behind it, there was a big wide shield which read: 'Varsovians, go to the baths. Get new linen, have your documents, money and valuables ready and hand them in at the cashier's office. After the bath, you will get them back'".

In December 1942-January 1943, on the orders of F. Stangl, the ramp was transformed to resemble a fake station. The space was marked with various signs: "The station was named “Obermeidan 1" ("Obermeidan"). "Bialystok" and "Volkovysk" banners were placed, thus demonstrating the transit nature of the Obermeidan station. Furthermore, there was a "Cashier's Office" sign, with a typical station clock mounted above it. All this was a sham. The station had nothing to do with either Bialystok or Volkovysk. The ticket office was inactive", M. Korytnicki described the new look of the station. However, all this only had an impact in a hurry, when those being deported did not have the time or energy to clearly understand what was happening. A superficial imitation was enough for those who wanted to be deceived. Moreover, as one moved towards the gas chamber, the terror against the doomed increased. Т. Greenberg testified to this in great detail in his testimony of September 1944: "During the undressing, SS Unterscharführer Franz Suchomel was rushing people, telling them that the water would get cold in the bath, while also saying that soap and towels would be handed out in the bathhouse. When people undressed, their group of five or six thousand was chased down the corridor from the dressing rooms to the 'bath house'. And if at the moment of undressing people were being beaten with whips by the Wachmänner guards, then the moment when they were driven into the 'bath house' the real atrocities began. Along the wire corridor leading to the ‘bathhouse’, Ukrainian Wachmänner stood with whips in their hands, mercilessly beating women, children and men as they passed, and at that moment the screams and cries of women and children rang through the camp, who, mad with fear and pain, ran themselves to the 'bathhouse', not knowing what awaited them there".

Naked people were searched for hidden jewellery, and at the entrance to the gas chambers, the Wachmänner could be downright sadistic. A. Goldfarb told of the tank engine operator Ivan Marchenko, who was particularly cruel: "When I was busy carrying corpses from the chambers to the pit, there was a terrible picture of mutilated people. Apart from being gassed in these chambers, many of them had their ears, noses, other organs and bodies cut off, and women had their breasts cut off. Thus the subtle method of gas poisoning was compounded by the physical death throes of inflicted mutilation". At almost every stage of deportations – organisation of deportation groups, unloading at stations, undressing, entering gas chambers, disposal of bodies – the Nazis used Jews for this ‘work’. It was not just a forced technical measure but also had a special perverse meaning in the eyes of SS, being direct proof that they, the Jews really are a |inferior race”, since they kill their fellow countrymen. Jankiel Wiernik recounted the words of Kurt Franz: “The art of the Germans, he said, is that they can control themselves in any situation. That is why the Germans are running the deportations in such a way that the Jews are crowding into the wagons, not knowing what is waiting for them". Describing the process of deportations and extermination of the Jews, we must not forget that this flow was not stable throughout the entire existence of Treblinka. Precisely because the survivors extrapolated data from the period of maximum "loading" to the entire existence of the death camp, as early as autumn 1944 Soviet documents referred to the alleged 3 million Jews exterminated.

The peak of deportations actually occurred in 1942. According to a telegram sent by Hermann Höfle to SS Sturmbannführer Adolf Eichmann in Berlin on 11 January 1943, 1,274,166 Jews were killed in four death camps – Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka and Majdanek – during 1942. Of these, 713,555 were killed in Treblinka (435,500 – in Belzec, just over 101,300 – in Sobibor, and 24,700 – in Majdanek). This telegram, intercepted by the British and only discovered in the early 2000s, confirmed earlier estimates by historians based on alternative sources - documents from the German Imperial Railway, the Reichsbahn, and its division in the General Governorate, the Ostbahn. The alternative registration of the trains was also kept by Franciszek Ząbecki, a member of the Polish nationalist underground, who worked at the Treblinka station throughout the existence of these camps. However, his testimony should be treated with a pinch of salt. After the Red Army had liberated these territories, he, like some prisoners, spoke of 3 million murdered, and in the post-war years, of 1.2 million. It is, therefore, no exaggeration to say that Treblinka was the key place of extermination of the Jews in 1942. As mentioned above, Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto were originally sent here. By 22 September, at the end of the first mass "relocation", up to 320,000 people had been exterminated here. During the first three weeks of the camp's existence, between 5,000 and 7,500 doomed to death were brought there every day.

The deportations from Radom District began on 5 August, and from 19 August – from other parts of the General Governorate. There was a temporary halt in the deportations from 29 August to 2 September, but they were resumed very soon, because of the army's reorganisation. The daily number of Jews, however, again varied: for example, on 6 September there were 13,500 Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto, and on 12 September – "only" 4,800. In September, deportations started from the Czestochowa Ghetto, and in November, there were trains from Białystok, Grodno, Druskininkai and other areas of the General Governorate.

In October, trains were sent to Treblinka from the Theresienstadt Ghetto, where mainly Czech and German Jews were held. In mid- and late October, several trains arrived from the eastern districts of the Third Reich. From mid-December 1942, however, deportations were halted for about a month. Because of the difficult situation at Stalingrad, the German military command needed extra railways and wagons. Having learned of this in advance, Himmler obtained from the OKW and the Ministry of Transport the provision of several trains that would allow the extermination of the Jews to continue.

Thus, in the second half of December 1942, 10,000 doomed people arrived at Treblinka. In 1943, the camp had seen no more deportations of such magnitude. On January 18, the second phase of the extermination of the Warsaw ghetto began, but due to resistance, only up to 8,000 Jews were deported. In February, several trains from the Białystok and Grodno Ghettos arrived. In March, Jews were shipped in from areas occupied by German and Bulgarian forces (the Bulgarian Jews themselves were not handed over to the Nazis) and from certain areas of former Poland. In April, from the Warsaw and Węgrów Ghettos. Thus, Treblinka gradually gave up its place as "leading" among the "death factories".

Initially, it was an echo of the events at Stalingrad, then in Warsaw itself. With the "Final Solution of the Jewish Question" in the territory of the General Governorate, the number of those condemned to death decreased, and in some cases, it was more economical to send the remaining ones to other extermination centres. In Majdanek, for example, the peak of the deportations took place in the spring and early summer of 1943, due to the mass actions in the Zamosc region. As Operation Reinhard was winding down, the role of Auschwitz as a centre of extermination also increased. Its commandant, Rudolf Hoess, gradually won the right to be called "chief executioner" from Odilo Globocnik. Moreover, the victories of the Red Army required Germany to mobilise the workforce, and therefore the Nazis could not afford to waste "useful Jews" as actively as before. As a result, the total number of those killed was difficult to calculate.

Initially, the prisoners said that 3 million people were killed, which is clearly an exaggeration. Polish judge Zdzislaw Lukaszkiewicz, who immediately after the war studied the subject of death camps, wrote that the number of victims was at least 780,000. The verdict of the 1965 Treblinka trials held at Düsseldorf cited a minimum of 700,000 killed. Contemporary estimates are also tentative, but the number often encountered ranges from 850,000 (Martin Gilbert and Yitzhak Arad) to 870,000 (Yad Vashem Museum) and 925,000 (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). The Treblinka Museum itself states that at least 800,000 people were murdered here.

Among the camp’s famous victims were the educator Janusz Korczak and his pupils, sisters of the founder of psychoanalysis Sigmund Freud, the musician Simon Pullman, the daughter of Esperanto inventor Zophia Zamenhof, and the young Chekhov's fiancée, Evdokia Efros. Among those murdered were the well-known publicist and member of the resistance Motya Dobin, the Polish-Jewish poet Franciszka Arnsztajnowa, the Jewish religious philosopher Hillel Zeitlin, the poet and publisher Aron Luboszycki, and Stefania Wilczynska, an employee of Janusz Korczak. Although the Treblinka death camp was established to exterminate Jews, they were not the only ethnic group. It is considered that up to 2,000 Roma, including natives of Bessarabia, were also murdered there. They were murdered in the gas chambers together with the others.

Terror Totality and Resistance Practices

No doubt, the death camp itself was a system of terror designed to crush and destroy the personality of every prisoner, turning him into an obedient tool. The arsenal of methods included: constant and indiscriminate beatings, elements of military discipline (morning and evening dressing times, drills, marching in formation, later to camp songs), punishment by whipping and shooting for faults (at times even those who had not been involved in the breach of discipline), and minimum rations. For the purposes of camp management, as in other camps, the Nazis segregated a group of "privileged prisoners" - the warden, the Kapo and the Vorarbeiter - who formed what was called camp self-administration. There were also some forthright spies among the camp prisoners who would inform the leadership of what was going on (Jankiel Wiernik mentions some of them in his memoirs). Of course, the environment of the death camp itself had an oppressive effect on the psyche of those who were temporarily kept alive.

The first days were a shock, a terrible trauma, shattering one's consciousness. The impossibility of comprehending the swift and inexorable loss of one's loved ones is what the survivors recounted in their memories of the days when the SS officers randomly decided at the reception area who would live and who would die. As A. Bomba recalled, “and so the day passed: twenty-four hours without water, without everything. We could neither drink nor eat, nothing could fit in our mouths, we had no appetite. At the thought that just a minute, just an hour ago, we had a family - a wife, a husband... and suddenly all at once everything was gone”.

Some committed suicide after the first few days, others continued to cling to life. However, the lack of hope turned it into existence and a de facto survival, which meant living only for today. The camp environment itself led to a perverted conception of life. Thus, each new train meant not only thousands of people sent to the gas chambers but also their belongings and - most importantly! - Food which one could steal and prolong one's existence. And at the same time, as Jankiel Wiernik confessed: "I have learned to look at every living person as a corpse, which he would become in the near future. I assessed him with my gaze, thought about his weight, who would drag him to the grave and how many whips he would receive in the process". Although Treblinka was a space of total terror, it would be wrong to say that it turned into an area of total control. This is primarily because the classic SS concentration camp was designed precisely for the regular exploitation and control of human resources. Contrary, the efforts of the members of the SS-Sonderkommando Treblinka were devoted to maintaining the conveyor belt of extermination and robbery of deportees, and prisoners were seen only as "living corpses", whose death was inevitably postponed. Thus, the structure of this death camp was modelled on that of a classical concentration camp but was simplified: there was no extensive administrative structure, prisoners were not quarantined, not loaned out to other companies, did not wear identical uniforms, and were not given a shaved head or number until a certain point. Similar to Sobibor, the prisoners constantly wore civilian clothes left over from the dead and could change them as needed. At night, even though they were locked up in the barracks, they were, as recollections show, able to communicate with one another, albeit with caution. Another issue was related to nutrition.

The norms described above effectively meant starvation and painful death, but in the belongings of those sent to the gas chambers, they found foodstuffs that they were officially prohibited from taking, and which, however, kept the survivors alive and enabled them to maintain their subsistence. Samuel Willenberg described in detail how they ate these foods in the barracks after lights out: “Others, and I among them, took out empty tin cans, which were used as stoves here. We cut three triangular holes in the top of the can, and put candles, cotton wicks, in the bucket and lit them. On these cookers, we put clay pots given to us by the old residents of the barracks, and in them, we boiled a mixture of cocoa flakes, sugar and fat, and that was our only food during that day”. The camp’s administration was likely aware of these alternative methods of supply and showed no zeal to prevent them. Not surprisingly, in early 1943, when the flow of trains stopped, there was a de facto famine among the camp workers, and the wait for a new train took place with the hope of quenching it and thereby surviving. Although the 'lower' and 'upper' camps were separated, prisoners were able to interact with one another. In this respect, for example, Treblinka differed from Sobibor. For example, Jankiel Wiernik, as a carpenter, was given a privileged position and was able to move between the two camps for a number of jobs. In 1943, prisoners of the "lower camp" were periodically transferred to the "upper camp" as needed. The baker Leileisen also performed the role of liaison. Increasing corruption also helped in circumventing these bans. For example, Samuel Willenberg recounted the case of several prisoners who came down from the berm under the guard of a Wachman asking for food.

For a bribe, the guard allowed not only food but also socialising. As in the concentration camps, the administration also maintained order by indirect methods, including a network of its own informers. Treblinka, however, housed one group of prisoners, the Jews, and therefore it was impossible to play against and pit different categories of inmates against one another (political prisoners, criminals, prisoners of war and so on). Classical SS camp management was always based on the privileged prisoners - various 'Kapo' groups, who were the eyes and ears of the SS, and many of them were especially zealous in maintaining order and bullying the inmates worse than the Germans were. The opposite was true of Treblinka: for most of its history, the camp chief was Galewski, who from the spring of 1943 was one of the key figures in the underground. It is difficult to overestimate the role he and his assistants played in alleviating the plight of the prisoners. As Willenberg witnessed, the Vorarbeiter's cruelty was often faked in full view of the Germans: they deliberately demonstrated beatings to satisfy the SS by simulating executions. Furthermore, to limit the time spent in the toilets, the Germans had a Jew watching over them in spring 1943, but in reality, the latrines were, under his watch, a place for meetings and news exchange. Without the help of the members of the "camp self-administration," other forms of mutual support were also impossible. During the typhus epidemic in the winter months of 1943 (when the cold and starvation due to the lack of transports became evident), headman Galewski hid the sick, lest they be shot, while working in the fur warehouses: "They were hidden from the eyes of the SS, covered with furs, and they slept all day. Their comrades, risking their lives, gave them hot tea, which was cautiously brewed in the corners of the barracks. Some of these sick people overcame the crisis and recovered. The place was more or less safe, as the Germans did not enter it for fear of lice". The history of the camp is therefore inseparable from the history of the networks of mutual support that developed between the prisoners. Thus, when the echelons arrived, Galewski and other workers tried to look for acquaintances in order to save their lives by getting them one or another position. Samuel Reisman, for example, said that Galewski, who had convinced the camp leadership that he could act as an interpreter, saved his life. Similarly, Samuel Willenberg got "life-saving advice" from his compatriot from Czestochowa. Of course, one should not exaggerate the degree of trust within the prisoners. For example, members of the underground were constantly afraid of being betrayed by snitches. Many were jealous of the "Golden Jews" because of their comparatively privileged position ("They wore elegant coats and coloured scarves". They looked more like bankers than prisoners", wrote Samuel Willenberg). The attitude towards the doctors, who administered pre-medication injections to sick prisoners before sending them to the 'infirmary', was also controversial. In other words, beyond the limits of official control and systematic terror, Treblinka was a very lively camp space, whose singularity was fuelled both by its proximity to a veritable death factory and by rampant corruption. Since discipline was to be impeccably enforced, the role of "useful Jews" increased, who could provide the patrons with found gold, money, useful objects, articles of clothing and so on. It was the same with the Wachmänner: they could almost kill Jews without any hindrance but it was forbidden to communicate with them, and getting valuable things (money and gold) could have very unfortunate consequences, so both sides preferred to keep the deals secret.

As a rule, Jews exchanged food from the guards, and purchases could also be made in a non-contact manner to avoid the unexpected appearance of the Germans. Samuel Willenberg told of a deal with one Wachman guard in the "infirmary": in exchange for 100 dollars, he pointed him to a pile of sand in which a bag of vodka, bread and sausage was buried. He had to "accidentally" drop a blanket on the spot in order to retrieve the purchase and carry it to the barracks. According to his own testimony, regular transactions between Jews and the guards took place through the window of the latrine. The exchange chain did not stop there at all, as the guards themselves had an active economic relationship with the local population. Gold, jewellery and money were exchanged for food, drink and sexual services.

The latter were provided not only by the local village girls but also by prostitutes who came all the way from Warsaw. For Poles, however, such corrupt relations were liable to punishment, e.g. imprisonment in a neighbouring labour camp. The corruption was noticeable and could lead to rather bizarre alliances, as Samuel Willenberg recounted in his account of his time in the "camouflage brigade", which in the spring and summer of 1943 collected coniferous branches for fences in the forest. This brigade commander, SS-man Hermann Sydow, would ostentatiously leave, after which the guards would collect money and exchange it for food from the Poles who were waiting for them. They themselves, like the SS man, were not left stranded. Even when August Miete replaced Hermann Sydow during his leave, the speculation did not stop. Strange as it may seem, these corrupt schemes were derived from the system of violence: everyone in the chain knew that if they were exposed, they risked punishment: beatings and death for the Jews, reprimands and disciplinary action for the Wachmänner guards. The Germans were the least worried: with Franz Stangl detached, the SS could only fear the young Kurt Franz. Although they occasionally organised "raids".

For example, Jankiel Wiernik testified that once the "Golden Jews", who in turn were regularly blackmailed by the Wachmänner, were searched and a considerable amount of jewellery was found: "They could not confess that they were doing it under pressure, because nothing would help them anyway. The torture began. The golden caged bird's dream of freedom was over. Now they were worse off than the other workers were. After this incident, only half of them remained, before there were 150 of them”. All this vividly illustrates the fact that even in the realm of total terror there remains room for internal resistance and the building of networks of mutual assistance. These were the very ground on which the insurgency had grown up.

Reference:

The book consists of three parts. The first is research material. It includes: an article by Konstantin Pakhalyuk and Mikhail Edelstein on the history of Treblinka in general; an article by Israeli historian Aaron Schneier on the “Trawniki” or Wachmänner guards (mostly former Soviet prisoners of war who defected to the enemy and played one of the key roles in the functioning of the extermination camps); an article by researcher Sergei Romanov, which refutes in detail the “arguments” of deniers of Nazi atrocities in Treblinka. The second part features the memoirs of two Treblinka prisoners, for the first time published in Russian, who became key sources in Holocaust historiography: memoirs by Jankiel Wiernik and Samuel Willenberg. The third part brings together a complex of never-before fully published documents prepared by the Soviet investigative authorities in August-October 1994: testimonies and records of examinations of 35 former prisoners of the Treblinka camps and local residents-witnesses to the crimes.