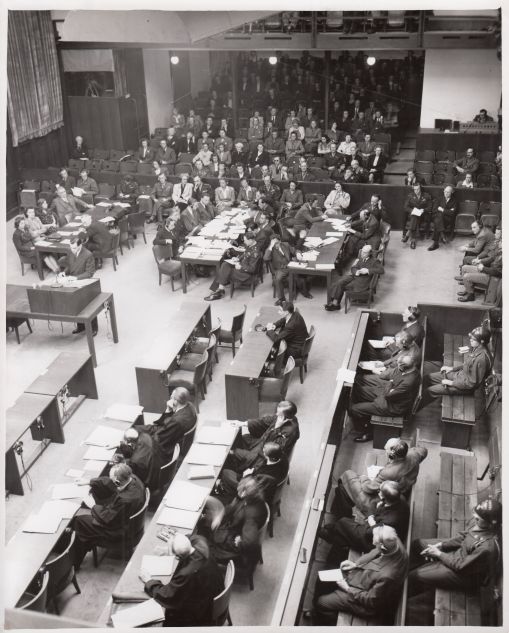

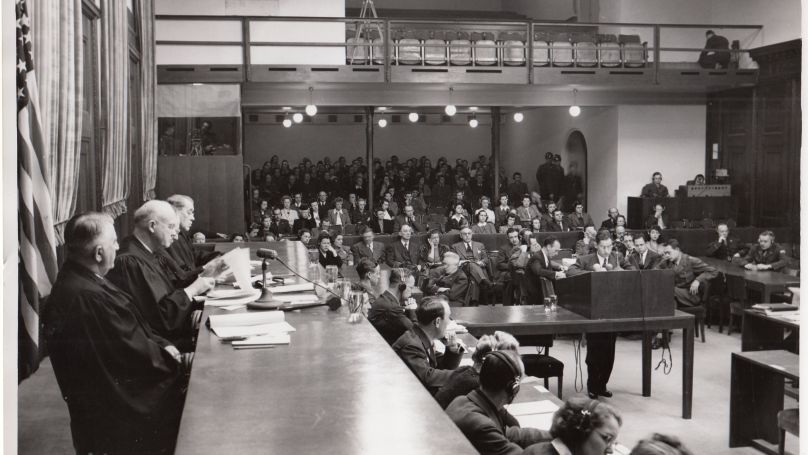

The history of the twelve Subsequent Nuremberg Trials, described in the “Nuremberg: Casus Pacis” project, features a strange paradox. As a rule, these trials handed down fair sentences to Nazi officials, executives and generals. Judges handed down long prison sentences, life sentences, and death sentences. However, almost all sentences had been commuted by the mid-1950s, and those convicted went free.

Why did it happen that way?

In the second half of the 1940s, in the wake of the Allied victory and under the influence of the victorious powers, there was a prevailing desire in Germany to give the bad guys what they deserved. But in the 1950s, a different idea prevailed.

For example, Alfried Krupp, the heir and closest assistant to the owner of the companies that supplied Hitler with arms. More than 23,000 prisoners of war and almost 5,000 concentration camp prisoners worked in slave-like conditions in his factories. For these crimes, Alfried got 12 years in prison and his property was confiscated. Is that fair? It certainly wasn’t cruel. However, after three years, Alfried was released and had all of his property returned. He never pleaded guilty.

On the other hand, another example was that of General of Sappers Walter Kuntze, Commander in Chief of the German Army in the South East. He introduced the rule that a hundred Serbs were to be shot for every German soldier killed and fifty for every wounded soldier. “The more unambiguous and harsh the repressive measures are applied from the beginning, the less there will be a need to apply them later. No false sentimentality!” he wrote in 1942. The court sentenced him to life imprisonment. Fair enough? Quite so. Nevertheless, in 1953, Kuntze was released.

And the most outrageous example is of SS Standartenführer (Colonel) Walter Blume, SS commander and leader of Sonderkommando 7a. According to his own records, his subordinates murdered 24,000 people in Belorussia and Russia between June and September 1941, just for being Jews or Communists. Blume knew this and had no qualms about it. He was sentenced to death at the Einsatzgruppen Trial. Is that fair? Fair enough. But the high commissioner of the American zone of occupation pardoned Blume and his execution was commuted to 25 years imprisonment. The Standartenführer did not serve these, either: he was released in 1955, became a businessman, and lived until 1974. Ten of the fourteen defendants sentenced to death in the Einsatzgruppen Trial more or less shared his fate.

No, I am not saying that they should all have been convicted in a few days and hanged. American justice was sometimes strict, sometimes lenient, but quite humane. But to disregard the sentences and release criminals, so to speak, on the 10th anniversary of the Allied victory? It is not easy to explain something like that.

Let's not dwell on the past, said the intelligent and quite respectable people back then. Why remember what happened many years ago? Let's not speculate on history, let's not touch the wounds of the past. The defendants are valuable specialists, we will need them in peacetime.

The very idea of pushing the past aside and forgetting is highly contagious. Just look at the events in the Federal Republic of Germany in 1966. Following the chancellorship of Konrad Adenauer, the ardent anti-Nazi and Gestapo prisoner, the position was held by his faithful assistant Ludwig Erhard... a member of the Nazi party from 1933 to 1945; then an employee of the Reich Ministry of Propaganda, Kurt Georg Kiesinger became the Federal Chancellor.

How could this happen? It’s very simple. There was a parliamentary crisis and opponents were looking for a new head of government who was acceptable to all. Therefore, Kiesinger, the Prime Minister of Baden-Württemberg, seemed reasonable: he was not a star in the sky, but could speak – journalists dubbed him “King Silver Tongue”. His former membership in the NSDAP, where he worked for Dr. Goebbels, was not a formal barrier: after the war, Kiesinger served a year and a half in an American camp and was labelled as having been “denazified". And this was not the only example: many former Nazis were easily integrated into life in post-war Germany, holding government posts, running businesses and even taking part in the reconstruction of the army.

However, many Germans had not forgotten their past. In 1968, during a congress of the Christian Democrats Union in West Berlin, the Resistance activist and Nazi hunter Beate Klarsfeld slapped Chancellor Kiesinger in the face and called him a Nazi. Kiesinger, holding his cheek and almost crying, walked off the stage in silence and did not comment on the incident until his death.

In 1969, he had to give up the seat of federal chancellor. The new leader of West Germany was the leader of the Social Democratic Party of Germany Willy Brandt, a member of the anti-fascist underground who had worked as a journalist at the Nuremberg trials after the war. Yet he took steps not even Adenauer dared to take.

For example, Brandt acknowledged Germany's eastern border - it took a long time for the Christian Democrats to reject their claims to Silesia and Pomerania, which had fallen to Poland, and East Prussia, which had been divided between Poland and the USSR. And on 7 December 1970, in the Warsaw Ghetto, the Chancellor unexpectedly knelt down before the memorial to the victims of the uprising, thus acknowledging German responsibility for the millions of victims of World War II. Yet he himself had nothing to do with Nazism and had always fought against Hitler.

People in Germany did not immediately appreciate the gesture: 48% of West Germans initially found the “kneeling” to be excessive. But the Social Democrats won the next election. The same policy was continued by Brandt's successor Helmut Schmidt – incidentally, Germany's first Jewish leader.

In the 1970s and 1980s, under Schmidt and his successor, German unifier Helmut Kohl, the kind of all-German consensus that we are all familiar with was established. When the responsibility for the horrors of Nazism is held not by Hitler and a small group of his henchmen but by all German people. Because they believed it, they did not stop in time, they were complicit in the evil. Because they said "yes" or remained silent when they could have said "no". Because they continued their measured burger life while their compatriots mocked the people of the Soviet Union and bombed Britain, while millions of Jews and people of other nationalities were exterminated in death camps.

This is why “easy” treatment towards the defendants of the Subsequent Nuremberg Trials simply wouldn’t be possible in modern Germany. If a Nazi criminal is found today, he is tried to the fullest extent of the law, often regardless of his age. Although there is no guarantee that Nazism will not return, the memory of one's own mistakes is a powerful antidote to a misanthropic ideology.

And the answer here lies in how other countries should deal with their own history. And at the same time, why we should celebrate Victory Day on 9 May.

Because otherwise, the neo-Nazis will be celebrating their victory day on 20 April.

By Daniil Sidorov