16 October 1946 marked a long-awaited turning point in the history of the Third Reich and the Nuremberg Trials. The defendants, sentenced to death, met their end. The editors' team of the “Nuremberg: Casus Pacis” project presents a chronicle of the last hours of their lives. Disclaimer: Please note, this publication contains shocking content – the illustrations in the photo gallery are posthumous photographs of the executed.

No Pardon

The International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg sentenced twelve defendants to death, including Martin Bormann (in absentia). The verdict did not come as a surprise to them – rather, their neighbours in the dock were shocked to learn that they had avoided the gallows. On 31 August, all of the convicts gave their last words in Court. Only Hans Frank and Arthur Seyss-Inquart openly admitted their guilt. The others claimed either that they knew nothing about the crimes and had nothing to do with them or stated that they had been forced to carry out orders.

On 9-10 October, the Allied Control Council, at an emergency meeting in Berlin, considered the appeals of the defendants. Of those sentenced to death, only Ernst Kaltenbrunner did not plead for leniency, although at the trial he was the only one who claimed to have fought Nazism to the best of his ability and dared to disobey Hitler’s orders. The others asked for a pardon; the legal counsels for Hermann Göring, Julius Streicher and Hans Frank did so without the consent of their clients and Martin Bormann's counsel did so in the absence of his “principal”. Göring, Wilhelm Keitel, and Alfred Jodl also requested that if refused clemency, the gallows be replaced by a “noble execution” – a firing squad.

The Allied Control Council rejected all these motions, giving Bormann the right to submit another one within four days of his arrest. The French and American representatives on the council agreed to shoot Jodl, but not Göring or Keitel. However, since the Soviet and British representatives opposed the symbolic gesture towards Jodl, the verdict remained in force in this part as well.

Initially, they discussed the possibility of carrying out the execution in Berlin. However, in the end, it was decided to carry out the execution there, in Nuremberg, both for security reasons and to ensure that the place of death of the Nazi leaders never became a place for cult worship afterwards.

“The trial is over. We journalists have nothing more to do here. But the press won't leave. All the rooms in the press camp are occupied, there are not enough seats in the dining hall, the bar counter is jammed. The cocktail list in red shows [barman] David's new creation, called John Woods,” the Soviet writer Boris Polevoy recalled in his book “The Final Reckoning: Nuremberg Diaries”.

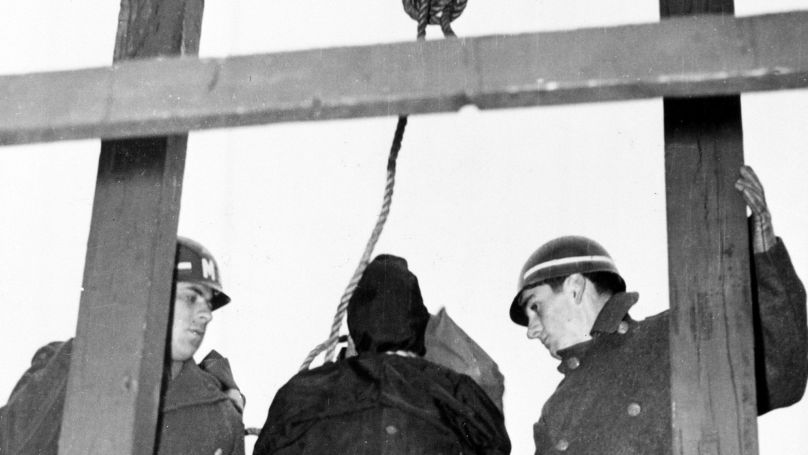

Hangman’s Finest Hour

According to Polevoy, Master Sergeant Woods, an American army sergeant who volunteered to carry out the Nuremberg tribunal sentence, became “the new celebrity of the press camp”: “I’ve seen Woods – a short, massive guy with a long, fleshy, hooked nose and a triple chin. The man boldly signs autographs and gives interviews, smiling and posing for the cameras, and one crafty reporter, who knows how, even managed to get a picture of him with a roll of twisted rope. The job he has undertaken is a necessary and useful one.”

Since Nuremberg was in the American occupation zone, the executioner had to be an American. And given the specifics of what was going to happen, a military man, too. John C. Wood, 43, was not in the military – he enlisted at short notice, was rapidly promoted to the rank of master sergeant, and sent on a special flight to Nuremberg. Despite his purely civilian experience, Woods was probably the most experienced professional of his kind in the United States. A master of his craft, he’d spent his life carrying out executions in San Antonio, Texas. By 1946, he had carried out a total of 347 executions in his 15 years on the job. The rumour had it that he was not cruel and that he usually used some special techniques to ease the last moments of his victims – immediately after the footing collapsed from under the hanged man, he pulled him by the legs with his weight so that the cervical vertebrae would break swiftly. However, Woods did not intend to apply this merciful trick to the defendants of the Nuremberg trials.

The curious thing was that Woods was advised by “one of the locals”, his German colleague Johann Baptist Reichhart, who had previously been a successful professional in the Reich and had executed hundreds, if not thousands, of people sentenced to death by the Nazi regime.

Final Report

Just three days earlier, American guards had been playing basketball here. Now the gymnasium in the courtyard of Nuremberg Prison was to be the scene of the execution of “the greatest heroes of the Millennium Reich”. Because the place was small, only a limited number of journalists were allowed in. That was eight, two from each of the Allied powers. “We, the Soviet press, were allotted only two seats: for a chronicler and a photojournalist. By our common consent, these slots were given to TASS correspondent Boris Afanasyev, a serious and educated journalist, who had been in the ‘Nuremberg seat’ all nine months without leave, and to Pravda photographer Viktor Temin, who could not be refused because he would have died of a heart attack,” Polevoy said.

It was Temin with whose words Polevoy described the execution, reproducing his remarks literally and excluding “only a few naturalistic details and cleaning the language from figurative, too salty epithets”.

“Well, we have come together, and this same [Commandant of the Nuremberg Palace of Justice] Colonel [Burton] Andrus met us in court, in a special room where we had not been allowed before. And this same Andrus told us not to move from our seats during the execution, not to talk, and to be quiet in general,” Temin told Polevoy.

The journalists walked down the stairs to the cells of the prisoners: “We see it's a prison. Even I have never been there. It is interesting: a corridor, doors on each side, some intricate locks and lamps shining in, inside the cells. And, as it should be, wolves: ‘Come on, have a look, gentlemen journalists...’ I do not know whether they, those eleven, knew that they were going to be executed today, but there was no fuss in the cells. Someone was reading, someone was writing something. Ribbentrop, I think, was talking to a priest, and one must have been brushing his teeth in preparation for bed...”

After lights out, Colonel Andrus led the journalists across the prison yard, lit by lanterns, into the gymnasium building. “It was empty in there. Three green scaffolds – like big boxes or something,” Temin described. “Steps leading up to them – I counted thirteen steps – and ropes hanging down to them from above. In front of the scaffold – seats for the representatives of the four armies. At the back – benches for the interpreters. And for us, for the press, special tables. Four tables. One of those Boris Vladimirovich Afanasyev and I have chosen.”

On the cast-iron blocks hung new, thick Manila ropes that could support a load of more than 200 kilogrammes. The base of the scaffold, over two metres high, was covered with a tarpaulin. Under each gallows was a trap with two flaps that could be opened with the push of a lever.

First to Go

Whitney R. Harris, a junior prosecutor on the team of Chief U.S. Prosecutor Robert Jackson, represented the patron at the executions, and on his return, he described the proceedings in detail, almost minute by minute, in a report.

At 9.30 p.m., reporters were allowed to inspect the cells and observe the sentenced prisoners. In particular, Fritz Saukel was pacing nervously back and forth, Joachim von Ribbentrop was talking to the chaplain, Jodl was writing a letter, and Göring was either asleep or pretending to be, with his hands over his blanket, as was his custom.

At 10.45 p.m., Göring's suicide disrupted the prescribed course of events – they had to divert their attention to clarify the circumstances and transport the body for a post-mortem examination.

At 11.45 p.m. all the sentenced criminals were served their last supper – a choice of sausages with potato salad or pancakes with fruit. Some of the death row inmates fell asleep and were later woken up. The fact that Göring had committed suicide an hour earlier was not announced, but because of that, the beginning of the execution had to be postponed and the planned ritual slightly altered. None of the former colleagues realised that Nazi No 2 had either done them one last favour by giving them a few extra minutes to live, or mocked them one last time by prolonging the inevitable.

Now, after Göring's final demarche, Ribbentrop was first in line for the gallows. At about 1 a.m. in his cell, Colonel Andrus read the sentence once more, Ribbentrop was led handcuffed to the place of execution, then the handcuffs were replaced with black rope and two soldiers of the military police escorted him up the 13 steps to the scaffold. They put him on the trapdoor, tied his legs, told him to identify himself and gave him the opportunity to say his last statement. It is interesting that, according to some accounts, Ribbentrop was almost in prostration, while others said he was firmly in control, gathering his last strength. In any case, after the last word, John Woods put a black cap on his face, then put a rope around his neck and tightened it.

Temin remembered this first execution as follows: “We hear, Göring, Göring... What happened to him? Did he run away or something? But there was no one to ask. And then we see Ribbentrop being led, not led, dragged under his arms. He seems to be completely out of it. He must be out of his mind from fear. They took him to the scaffold. They put him under the noose. A priest came up to him, whispered something. This same Sergeant John Woods put the cap on him, then the noose, then pulled the lever...”

Keitel was hanged next. International News Service correspondent Kingsbury Smith shared fresh impressions in a report on 16 October: “With both von Ribbentrop and Keitel hanging at the end of their rope there was a pause in the proceedings. The American colonel directing the executions asked the American general representing the United States on the Allied Control Commission if those present could smoke. An affirmative answer brought cigarettes into the hands of almost every one of the thirty-odd persons present. Officers and GIs walked around nervously or spoke a few words to one another in hushed voices while Allied correspondents scribbled furiously their notes on this historic though ghastly event.

In a few minutes, an American army doctor accompanied by a Russian army doctor and both carrying stethoscopes walked to the first scaffold, lifted the curtain and disappeared within.

They emerged at 1:30 a.m. and spoke to an American colonel. The colonel swung around and facing official witnesses snapped to attention to say, 'The man is dead.'

Two GIs quickly appeared with a stretcher which was carried up and lifted into the interior of the scaffold. The hangman mounted the gallows steps, took a large commando-type knife out of a sheath strapped to his side and cut the rope.

Von Ribbentrop's limp body with the black hood still over his head was removed to the far end of the room and placed behind a black canvas curtain. This had all taken less than ten minutes.

The directing colonel turned to the witnesses and said, ‘Cigarettes out, please, gentlemen’.”

First-Come, First-Served

The whole process of the first hanging took about half an hour, then the executioner and his assistants began to rush in order not to drag it out - another Nazi was led into the hall while the previous one was still dangling on the gallows. At first, they did not plan to immobilise their hands, but Göring's suicide prompted a change. Now the condemned were led from their cells to the gym, with their hands cuffed behind their backs, then on the approach to the gallows, the cuffs were replaced by a rope, which was only removed after the noose was put around their necks.

After stating their name, “the condemned walked up thirteen wooden steps to a platform eight feet high which also was eight square feet. Ropes were suspended from a crossbeam supported on two posts. A new one was used for each man.”

“When the trap was sprung, the victim dropped from sight in the interior of the scaffolding. The bottom of it was boarded up with wood on three sides and shielded by a dark canvas curtain on the fourth, so that no one saw the death struggles of the men dangling with broken necks,” said Boris Polevoy.

This conveyor belt - while the body of one is removed from the noose, a second is being prepared for hanging nearby - may have been the last reminder to the convicts of the millions of people who stood in line to be shot, for the gas chamber, the crematorium, or the same gallows. The execution of each one who allowed such a thing to happen not long ago took an average of 10 minutes. Woods would later proudly state in an interview the unprecedented speed at which he practiced his trade.

“It was a tricky thing to hang there, not as the Nazis did with ours. They put the rope on, pull the lever - and the criminal falls through the trapdoor of the platform. You can't see him suffocating there, only the rope trembling,” Temin explained. “This Woods must have had some training - he was good at it: he did all ten of them in an hour and a half - a master. When they dropped down, they were taken off the noose there, the doctor pronounced them dead, and they were put behind a curtain in black boxes. And each one had a nameplate on his chest.”

Some accounts suggest that for all his professionalism, Woods did not prepare the place of execution in the best way – who knows why – because of the lack of time or for some other reason. He did not properly calculate the length of the ropes and the depth and width of the trap. As the bodies fell, they hit the edges of the trapdoor, and this clearly added to the death throes. Moreover, the way the executioner chose, with the trapdoor and without the additional support was the most brutal version of hanging – the “long drop” method. According to some reports, because of an inadvertently or deliberately wrongly measured length of rope, death row inmates often died from slow asphyxiation rather than fractured cervical vertebrae. Ribbentrop died of asphyxiation in about 15 minutes, and the head of Field Marshal Keitel, who had also been in pain for a long time, was covered in blood after hitting the walls of the hatch.

In Alexander Lavrin's book “1001 Death”, the memoirs of the Soviet photojournalist are presented in a more dry form:

“At 0.55 a. m., all eight of us journalists were escorted to the place of execution and we took our designated seats against the scaffold at a distance of about three or four metres. Commission members, medical experts and American security officers enter. Five people from each of the Allied countries – the USSR, the United States, Britain and France – are present. These included a general, a doctor, an interpreter and two correspondents. Everyone else took their designated seats to the left of the scaffold. At the gallows on the scaffold, two American soldiers, an interpreter and an executioner, take their place. Joachim von Ribbentrop is brought in first, under his arms. <...>

...At 1.37 a. m. Kaltenbrunner is brought in. This monster was Himmler's right-hand man. He has running eyes and huge strangler's hands... Kaltenbrunner casts a pleading look at the pastor. The latter reads a prayer. Kaltenbrunner looks round with wandering eyes. But the impassive executioner throws a black hood over his head. All of us, 25 people present at the execution, people of different ranks, ages, nationalities, opinions, think alike at these moments: the perpetrators of war crimes must be punished severely and mercilessly”.

The order of execution was as follows: Ribbentrop; Keitel; Kaltenbrunner; Rosenberg; Frank; Wilhelm Frick; Streicher; Sauckel; Jodl; Seyss-Inquart.

Boris Polevoy noted that most of the criminals on the scaffold kept their spirits up. “Some behaved defiantly, others resigned themselves to their fate, but there were also those who cried out for God's mercy. All but Rosenberg made last-minute short statements. And only Julius Streicher mentioned Hitler”.

The Time magazine report described some of the reactions of the death row inmates. For example, Keitel climbed the scaffold like a rostrum, wearing a perfectly pressed uniform and polished boots; Streicher gave the impression of madness and tried to kick Woods and his assistants as they tightened the noose; Sauckel refused to put on his coat as he left the cell; Seyss-Inquart limped and dragged his leg and Alfred Rosenberg, the most talkative statesman and official party philosopher of the Third Reich, only whispered a single word in his dying moments: “No...”

International News Service correspondent Kingsbury Smith also shared his impressions in his report: “When he [Von Ribbentrop] was turned around on the platform to face the witnesses, he seemed to clench his teeth and raise his head with the old arrogance;

Keitel did not appear as tense as Von Ribbentrop. He held his head high while his hands were being tied and walked erect towards the gallows with a military bearing. When asked his name he responded loudly and mounted the gallows as he might have mounted a reviewing stand to take a salute from German armies. When he turned around atop the platform, he looked over the crowd with the iron-jawed haughtiness of a proud Prussian officer. After his blackbooted, uniformed body plunged through the trap, witnesses agreed Keitel had shown more courage on the scaffold than in the courtroom, where he had tried to shift his guilt upon the ghost of Hitler, claiming that all was the Führer's fault and that he merely carried out orders and had no responsibility;

Despite his avowed atheism, he [Rosenberg] was accompanied by a Protestant chaplain who followed him to the gallows and stood beside him praying;

Hans Frank was the only one of the condemned to enter the chamber with a smile on his countenance;

Streicher went down kicking. When the rope snapped taut with the body swinging wildly, groans could be heard from within the concealed interior of the scaffold. Finally, the hangman, who had descended from the gallows platform, lifted the black canvas curtain and went inside. Something happened that put a stop to the groans and brought the rope to a standstill. After it was over I was not in the mood to ask what he did, but I assume that he grabbed the swinging body and pulled down on it. We were all of the opinion that Streicher had been strangled”.

Whitney R. Harris also left some impressions of the last minutes of the condemned men in his report to prosecutor Jackson: “Keitel stated like a Prussian soldier”, “Kaltenbrunner spoke with an apologetic tone”, “Frank spoke very softly”, “Jodl spoke in the manner of an officer addressing his troops”. (All the last statements of the condemned are given in the photo gallery at the top of the material – ed. note)

John C. Woods would later admit more than once: “They all died as brave men”.

At 1.11 a.m. Ribbentrop was led into the hall, at 2.46 Seyss-Inquart fell through the trapdoor with a broken neck. Those responsible for the deaths of millions of people in agony over the years were dispatched to hell in less than two hours.

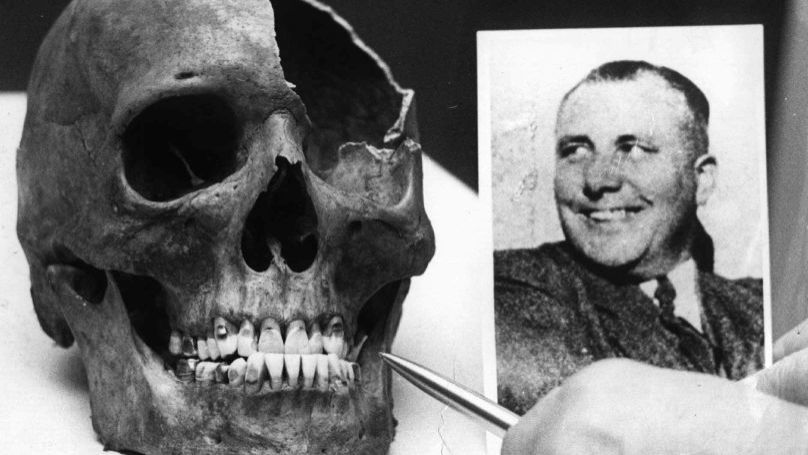

Final Road

After the execution, the journalists were allowed to inspect the criminals. Next to the bodies of those hanged, the corpse of Göring, who had committed suicide, was placed so that it would occupy a symbolic place under the gallows (furthermore, it was necessary to immediately rule out possible rumours of an escape, a switch, or a staged death of Nazi No 2). “We take a look – and what is it – ten of them were hanged, but all eleven of them are lying there. And Göring is here”, recalled Temin. The journalists took a photograph of each body – clothed and naked.

After the execution, each body was wrapped in a mattress, along with the last clothes he wore and the rope on which he was hanged, and placed in a coffin. “All the coffins were sealed. <...> At 4 a.m. the coffins were loaded into the 2.5-tonne trucks waiting in the prison yard, covered with a tarpaulin and driven off with a military escort”, says Boris Polevoy. “An American captain rode in the front car, followed by French and American generals. Then the trucks and a jeep guarding them with specially selected soldiers and a machine gun followed. The convoy drove through Nuremberg and, after leaving the city, headed south.”

At dawn, the vehicles approached Munich and headed immediately to the outskirts of the city, to a private crematorium. The owner was notified of the arrival of the bodies of 'fourteen American soldiers' to allay the possible suspicions of the staff. The crematorium building was surrounded, setting up radio communications with soldiers and tankers on the cordon in case of an alarm. Everyone who entered the crematorium could not leave for the rest of the day.

The coffins were unsealed and the bodies checked by the American, British, French and Soviet officers present at the execution. Thereafter the cremation began, which lasted all day. In the evening, the container with the ashes was taken out of the crematorium by car, the ashes, according to some reports, were scattered in the wind from a plane, while others said they were dumped off a bridge into the Isar River in Munich. There is no accurate data on this last action. It took place in utmost secrecy: it was decided to eliminate the slightest opportunity for potential Nazi followers and admirers to create a place of worship for the executed Third Reich’s top brass.

John Clarence Woods. Afterword

In 1948, John C. Wood was once again called upon to carry out the justice of historic proportions – he would hang seven Japanese war criminals in Sugamo Prison in Tokyo. His fame would last for quite some time - and the executioner would show remarkable enterprise in doing so. Newspapers around the world would print pictures of Woods proudly posing with a rope tied in a noose in the trademark way of thirteen knots. He sold “Nuremberg ropes” piece by piece – and buyers would never think of making the simplest calculation: if these scraps were really part of a hanging rope, it would be long enough for dozens of executed men.

In his interviews, he said: “I am proud that I hung those ten Nazis. I wasn't nervous - you can't allow yourself to be nervous in such a case. I want to put in a good word for the soldiers who helped me, it would be good for them to be promoted. That's a job somebody's got to do”.

A year and a half after the last Tokyo execution, John C. Woods himself died under bizarre circumstances that created many rumours. According to a milder version, he was electrocuted while repairing the wiring in his house. However, a darker legend says that the progressive executioner, wishing to keep up with the times, attempted to test an electric chair of his own design. He sat down on it, attached electrodes, and playfully told his assistant to switch on the current. The assistant automatically carried out the order.

To Whom, Dishonour

All the newspapers of the world paid tribute to the long-awaited, logical conclusion of the main trial of the century – some with dry news, others with an emotional article for a page, or even more. The majority of Western stories were based on a detailed report by the International News Agency, but the details were tailored as they saw fit. The headlines screamed from every newspaper tray, newsstand or bookshop window: “The End of the Nazis” and “The Nazis Destroyed” in The New York Times, “The Hangman's Hour” in the Chicago Daily Tribune... The Soviet papers relied primarily on the discreet communiqué of "truth-teller" Viktor Temin.

Triumphant reports that the greatest villains in the history of the 20th century had finally been punished were interspersed with alarming forecasts. Thus, the Daily Express correspondent wrote from Nuremberg:

“I fear that Nuremberg Prison may have given birth to a new legend of heroic Teutonic warriors,” and commented on the general tone of the farewell speeches, “Let us take a closer look at that theme 'God save Germany and make it great once more' which formed the essence of the last statements of all those hanged. And, above all, let’s consider Göring’s final challenge”.

An extremely curious detail was given by Time magazine on 28 October 1946 in a great piece on the procedure and details of the execution, “The Night Without Dawn”. Allegedly, at the very moment when the prison commotion caused by Göring's suicide began, “near the old Imperial Castle in Nuremberg a group of German children hung an image of Göring. They then burned the improvised pavement and silently walked around the fire, watching it cast strange shadows among the ruins”.

Prison psychologist Gustave Gilbert, whose long watch and round-the-clock surveillance of the defendants finally ended, wrote in his diary:

“The day after the death of the last top Nazi leaders, I asked one of the German lawyers what the German people were thinking about this end of the Third Reich. He thought a while, then said, ‘To tell you the truth, they think whatever you want them to think. If they know you are still pro-Nazi, they say, ‘Isn't it a shame the way our conquerors are taking revenge on our leaders!—Just wait!’ If they know you are disgusted with Nazism, and the misery and destruction it brought to Germany, they say, ‘It serves those dirty pigs right! Death is too good for them!’ You see, Herr Doktor, I am afraid that 12 years of Hitlerism has destroyed the moral fibre of our people”.

Sources:

Boris Polevoy, “The Final Reckoning: Nuremberg Diaries”

Bradley F Smith, “The Road to Nuremberg”

Description of the Executions of the Major War Criminals // Famous Trials