On 15 October 1946, the world received the sensational news – Hermann Göring who was sentenced to death by hanging, had committed suicide on the eve of his execution. He had escaped the disgrace of the “rope” and left this world on his terms. The defendant, known in the Third Reich as “Nazi No 2”, aspired to be “Number One” at the Nuremberg Trials. He was the only defendant who openly fought the International Military Tribunal, giving no quarter and never repenting for a moment. Göring was strikingly different from the other defendants, whom he despised for their "softness", "betrayal of ideals", "cowardice" and "treason against the fatherland". He was indeed a true Enemy, a personified Evil - and the prosecution had to fight him in a long, exhausting battle. Göring was a unique opponent. Despite his hatred, everyone around the proud “Nazi No 2” at Nuremberg 1945-46 recognised his bravery, steadfastness, and tough uncompromising character as a combat officer, an ace pilot. His behaviour at the trials was a chronicle of a diving bomber, right down to the ramming in the final act.

‘Martyr’

In his final statement at the trials, Hermann Göring said: “The victor will always be the judge and the vanquished the accused… I do not recognise the judgment of this court... I am glad that I have been sentenced to execution... because those who are sentenced to life imprisonment never become martyrs.”

His conduct at the process at first had the understandable purpose of getting off with prison. Then he realised that he would certainly not get away with it. He greeted the verdict with bravado: “Capital punishment means nothing to me. I stopped being afraid of punishment when I was twelve years old.”

In a suicide letter from 10 October 1946 to Churchill, he wrote:

“You think that you have arranged things cleverly by throwing this historical truth on the dissecting table for the legal sophistries of a handful of ambitious juridical subordinates, and allowing it to be turned into a dialectal treatise of paragraph-quibbling, although you as a Briton and a statesman know all too well that, by such means, the vital problems of the peoples could not in the past be solved or judged, and that they will not be so solved in the future. I have a too-well-founded opinion of your strength and of the cunning of your intelligence for me to think you capable of believing the vulgar catchwords which you sustain the war against us and seek to glorify your victory over us in a circus-like spectacle.”

Göring was worried but still felt fit.

Failed Hope

Most likely, he was driven by...ambition. Once he and no one else could be called "Nazi No 2". Then Reichsminister Hess, Reichsführer Himmler, Reichsleiter Bormann, even Reichspropagandist Goebbels began to claim this accolade... Now three of them were dead, and Hess had lost face before, due to his ill-fated solo trip to the UK. But most importantly, there was no more Hitler. Which meant...

...It meant that at the historic International Military Tribunal, at the main Nuremberg Trials, he, Reichsmarshal Göring, was finally no longer Number 2. He was automatically elevated to Nazi Number One.

As the trials went on, Göring's tactics were perhaps the most fascinating spectacle. He would mock the charges, then outright lie, then provoke the participants in the session. He was playing his part on the great stage of history - so it seemed to him. However, the end was simple and mundane. On the day of the announcement of the verdict, they spoke first about the others, and after the lunch break, at 2:50 p.m., they finally said: “The International Military Tribunal sentences you to death by hanging.” The judge added: “The guilt of this man is unprecedented and the crimes are so monstrous that there can be no justification.”

The last words were delivered, the letters written. Churchill did not reply.

All that was left was to become a martyr. Göring would have had the guts to go to the gallows for such a prospect. But perhaps he was indeed morally broken. He had ceased to believe in his impending martyrdom. Or perhaps his pride prompted him to take a different path - to get there first and do it his own way, not to fall into the hands of the victors.

The “Nuremberg: Casus Pacis” project has previously published a biographical sketch of Nazi No 2 (link). Let us recall the main milestones of Göring's journey – from a brave heroic aviator to a “downed pilot”.

Young Veteran

In 1914, the twenty-year-old infantryman Hermann Göring demanded to be transferred to aviation.

In the air squadron he became a mechanic, an observer, and within a year was promoted to reconnaissance pilot, then a bomber pilot and finally a fighter pilot. He was a truly fearless young man. He shot down 22 enemy planes. The holder of three orders, he rose to the rank of a commander of a fighter squadron and became a captain. After the war, he stayed on as an aviator, performing demonstration flights, went to university and married Carin von Kantzow, whom he took by storm from her Swedish husband.

He was tall (178 cm was considered tall at the time), unquestionably handsome, charming, courageous and ambitious... His life could have turned out very differently.

Brother-in-Arms

In 1922, he met Hitler in Munich, and immediately believed in him. But there was another circumstance - Karin believed in Hitler. She became almost more of a Nazi than Göring.

The Führer badly needed war heroes in his party. Göring was the most brilliant of them all. Hitler immediately appointed him the supreme leader of the Storm Units – Ernst Röhm and Göring would hate each other forever. And it was Göring who turned these gangs into a semblance of an army and imposed discipline. On 9 November 1923, he took part in the “Beer Hall Putsch”, marched hand in hand with Hitler, and was seriously wounded. His wife took him abroad for treatment. He recovered, but after that, he began to gain weight rapidly... He was eager to go to Germany, but the flustered Führer asked him to refrain and “keep himself for National Socialism”. While Hitler was in prison, Carin visited him and received confirmation – Göring remained his main and closest brother-in-arms.

No. 2

In 1927, he returned to Germany. His party career went like clockwork. As a war hero and ace pilot, he was a standard-bearer, even if his outward attractiveness suffered from the extra kilos. It was he who became President of the Reichstag and dismissed von Papen's government, clearing Hitler's path to power. It was he who created the secret state police, the Gestapo, and was the first to head it.

It was he who initiated the Night of the Long Knives and rid Hitler of the Storm Units and himself of Röhm. In 1935, he achieved a unique position in the Reich: he was declared a hero and Hitler's closest ally on several occasions and was given immunity and unlimited rights. He wanted to become the Reichsforstermeister – the country's forester – and so he did.

He wanted to be a general – and jumped to the rank of captain. He became a field marshal of aviation and headed the Luftwaffe. And in June 1941, he was officially appointed Hitler's successor in case of his death or other misfortune. On 30 July 1941 Göring signed a document on the “Final Solution to the Jewish Question”, providing for the extermination of some 20 million people.

And then Hitler began to doubt Göring: the latter was increasingly showing his second nature.

‘Pocket Money’

A curious excerpt from Goering's interrogation:

Where did you get the cash money from?

I was the second man in the country and always provided with money in abundance. I signed the allowance myself.

And this is the same way you received foreign funds, foreign exchange?

Yes. I myself was the final authority on this.

Did it have any correct procedure or were there any records made about it at all?

All that was needed – permission, but in my case, that was not even a question.

If you were travelling abroad and needed a large amount of currency, how did you get it?

I have never needed for too much money. If I was planning a trip abroad, I would calculate how much money I would need and then ask for the currency.

How did you get money before the war?

Like any private person who went abroad. I carried the cash needed in the first few days in my pocket, and for the rest, I got a letter of credit.

How did you pay for the purchase of the paintings?

Always in cash.

What is your yearly income?

As Reichsmarshal I received 20,000 marks a month, as Commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe I received 3,600 marks a month, tax deducted. As President of the Reichstag – 1600 marks. Furthermore, there were royalties for my literary works. The income from my books is about 1 million marks.

Did your lifestyle cost more than these sums?

Some of my expenses were covered by other funds; my residences in Berlin and Carinhall were financed by the state.

A Lifestyle and Its Cost

Göring's “executive flat” was built 60 km from Berlin by two architects: Werner March, who also designed Berlin’s Olympic Stadium, and Friedrich Hetzelt, who designed the Gestapo building in Prinz-Albert-Straße. The main country residence of Nazi No 2 was called “Carinhall”, in honour of his wife (when Carin died in 1931, her ashes were buried in a magnificent mausoleum on the grounds of the manor). The result was somewhere between a palace and a castle. Located nearby, there were hunting grounds in the Schorfheide Forest and two lakes, the Grossdöllner and Wuckersee. There were magnificent seven-metre high gates made of expensive stone, a gym, a menagerie, even a Russian bath. And in the attic and basement – a toy railway. After the end of the Battle of Stalingrad, Göring celebrated his birthday by playing “trains” with his guests.

On a whim, he would fly to Paris - often alone. Of course, a squadron of fighter jets accompanied him.

He also had his own museum. He did not buy paintings: masterpieces of world art were seized as “trophies” from conquered cities. Most of all Göring liked statues, especially lions. In 1945, he attempted to hide his collection in a mine or in tunnels near Hitler's residence, where he also had another "house", but failed. Those responsible for the delivery stole the valuable cargo, and individual works of art would “resurface” over the decades.

Did the purchases of paintings not exceed your income?

I had other sources of income...

Not only did the Göring family enjoy lions in the form of statues, but they also kept seven domesticated 'feline' carnivores, and the pets would occasionally roam freely in the house. A lioness named Bubi escaped from the estate in May 1945 and continued to scare people in the forest where she lived and hunted for a long time.

In short, Hitler said it best... about Carinhall. “My Berghof (the Führer's not-at-all small or cheap estate in the Bavarian Alps - author's note) certainly can't be compared with this. Perhaps, it could become a garden lodge here?”

The Führer began to ponder, as he looked at all this luxury.

Other Sources of Income

If one were to ask any German at the time which company in Germany was the most important, the richest and the most powerful, he would answer without a doubt: Reichswerke Hermann Göring. This gigantic financial-industrial corporation was created at Göring’s initiative. It was established using state funds; the goal was to merge into a single cycle the production of steel, from iron ore mining to military production. German bankers and industrial bosses tried to resist, but Göring had an effective tool readily available for resolving economic disputes – the Gestapo. After a week of telephone tapping, the author of the “German economic miracle”, Hjalmar Schacht, resigned and the steel tycoons were nailed. Incidentally, the organisation that technically controlled the radio and telephone networks in the Reich was called the “Hermann Göring Research Institute”.

Once industrialists and financiers had trusted Schacht's entreaties, Hitler's speeches, Göring's charms and invested in Nazism in the hope of consolidating the position of their enterprises and assets. Now they were subjected to the planned economy, their profits were limited to a maximum of 6 percent, and the Anschluss of Austria added another interesting detail: German banks and private investors owned many Austrian enterprises, but now it all went to the Reichswerke Hermann Göring. The same thing happened with the industrial property in other occupied countries – Skoda factories in Czechoslovakia, Renault in France... By the end of 1941, Reichswerke Hermann Göring had a capitalisation of 2.4 billion marks and it was the largest industrial conglomerate in Europe.

However, Göring did not own this corporation. He chose the status of “trustee for the German state”, receiving dividends as manager and observer. Naturally, the corporation exploited the slave labour of concentration camp prisoners and “displaced persons” deported from all over Europe. The Stahlwerke Braunschweig plant employed 10,000 slaves and the mining operation – 47,000. Göring's corporation kept growing, devouring new shipbuilding, construction, steel, iron-cast and transport facilities.

The most accurate definition of Hermann Göring's position under the Nazi regime is that of the chief beneficiary. And the chief corruptor.

The Untouchable

The cooling on Hitler's part towards the favourite coincided with the outbreak of war with the Soviet Union. In 1941, sensible strategists and economists had the darkest forebodings about the outcome and consequences of the campaign; in 1942, Hitler began to push Göring away from real power. The influence and power of Nazi No 2 narrowed considerably with the appointment of the architect Albert Speer as Reichsminister of Armaments and War Production. Göring took a sharp dislike to Speer and actively opposed him, and it was to this staunch opponent that he said at the end of 1942: “We shall yet rejoice if after this war Germany maintains its 1933 borders.”

At the end of the Battle of Stalingrad, Göring had to give Hitler his word that he would provide provisions, ammunition and medical supplies to the surrounded units by air. However, this was no longer possible. Soviet soldiers won the field war; the war on the home front was lost by the German economy. And the Soviet Pokryshkins and Kozhedubs became the masters of the air.

It was still impossible to touch Göring, although he was clearly losing ground and gradually stopped even appearing in Berlin. At his pompous estate, he divided his leisure time between hunting, bathing, toy trains, a wine cellar and... Morphine in unlimited quantities. In order to bring Göring before the International Military Tribunal, the Allies had to treat him for this drug addiction. It resulted in polarised mood swings, outbursts of rage and prolonged apathy. He became addicted to morphine after the “Beer Hall Putsch”, when he was seriously wounded, resulting in inflammation in the groin and other unpleasant consequences. Since then, he always had a supply of pills and ampoules with him.

He progressed to the point of an almost complete breakdown of his personality, accompanied by eccentric provocations. He painted his nails and lips. He ordered new outfits from tailors almost every day, such as red boots with gold spurs, blue trousers with stripes, overcoats with fox and beaver collars, white coats with blue and red lapels... Albert Speer recalled: “I still remember being struck by his red, polished nails and powdered face. By then I had gotten used to the fact that his green brocade gown always had a huge brooch on it.” The Third Reich's claim to have inherited Ancient Rome was also evident at this almost-caricature level: Göring fully embodied the image of a debauched Roman patrician during the decline of the empire.

A curious detail: albeit ruthless and indifferent to the outside world, Nazi No 2 was an excellent family man. His marriage to his second wife was certainly a happy one. He married the actress Emmy Sonnemann in 1935, and she unofficially became First Lady of the Third Reich. His daughter Edda idolised her father. Not only that, he saved his brother Albert from arrest many times - who in turn saved several dozen Jews from death, which was no secret to Nazi No 2.

He was almost forgotten. And suddenly, on 23 April 1945, Hitler, who had just called everybody around him cowards and traitors and who had decided to remain in Berlin to the very end, received a radiogram: “My Führer! In view of your decision to remain in Berlin, do you agree that I should immediately assume as your successor according to the law of 29 June 1941; the general leadership of the Reich with full freedom of action at home and abroad? If I do not receive a reply by 10 p.m., I shall take it as confirmation that you have no freedom of action and that the conditions demanded in your decree are in place, and I shall act for the good of our country and our people. You know how I feel about you in this most difficult hour of my life. I am unable to put it into words. May God protect you and bring you here quickly, no matter what. Your ever devoted Göring”.

Hitler regarded this defiant ultimatum as proof of his treacherous intention to seize power. On the same day, Göring was arrested on charges of high treason and on 29 April Hitler stripped him of his ranks, decorations and posts and expelled him from the party. He was on the way to being put before a firing squad.

However, Göring’s personal pilots freed him, and a week later, he was in Allied hands, and they had to take care of his health. However, in the end, he had time to give the final order to blow up Carinhall. On 8 May, he proudly went to meet an American lieutenant and identified himself. He introduced himself: “Lieutenant Shapiro”. Göring sighed heavily: “Of course, a Jew”.

The Final Battle

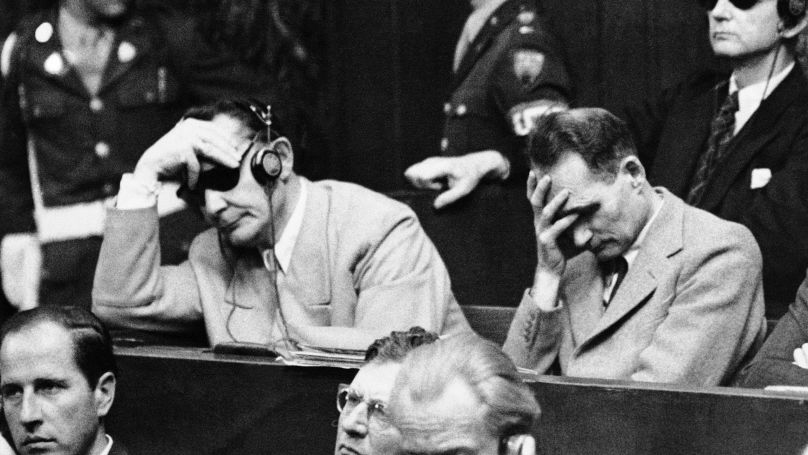

The prison psychologist Gustave Gilbert and the psychiatrist Douglas Kelley recorded in detail Göring's behaviour at the Nuremberg trials, his reactions, and communication patterns with other defendants. Kelley, as it later became clear, was unable to resist the charisma of his patient. He became the messenger between Göring and his wife and daughter, delivering their letters, and was staggered by the contrast: the deep tenderness of the family man Göring, and the utter callousness and lack of remorse of Goring the Reichsmarschall. Subsequently, Kelley was never freed from the charms of his chief patient, and would commit suicide.

Gustave Gilbert, in The Nuremberg Diary, recorded his regular conversations with Göring as well as his observations. According to him, Nazi Number 2 differed significantly from the other figures: he was characterised by consistency and an integrity of views, which he was adamantly unwilling to reconsider. His IQ was an impressive 138.

“He reacted with keen interest to the challenge of an intelligence test, and by the end of the first subtest (memory-span), he was acting like a bright and egotistical schoolboy, anxious to show off before the teacher. He chuckled with glee as I showed surprise at his accomplishment in the increasingly difficult digit series. He slapped his thighs and pounded his bed impatiently when he failed on 9 forward and 7 backward, and pleaded for a third and a fourth try at it. ‘Oh, come on, give me another crack at it; I can do it!’ When he finally succeeded, to my expressed amazement, he could hardly contain his joy, and swelled with pride. This pattern of rapport was maintained throughout the entire test, the examiner encouraging him with remarks of how few people are able to do the next problem, and Göring responding like a show-off schoolboy. Göring was given to understand that he had the highest rating so far. He decided the American psychologists really had something there. ‘The method is good—much better than the stuff our psychologists were fooling around with’.”

He considered the films shown at the trial about Nazi atrocities to be propaganda forgeries. He defiantly took off his headphones so as not to listen to the testimony. In prison, he tried to take a leadership position over the rest of the defendants, scheming on walks and at dinner, creating small situational coalitions, and in the end, turned even the most loyal ones against him – it came down to a boycott. He used remnants of influence, down to intimidation, to create a general line of opposition to the court. He provoked the judges with defiant, cynical “gallows humour” and impertinent remarks from the bench. He became enraged at sessions, accusing those confessed of criminal acts of complicity in treason. Paradoxically he remained loyal to Hitler, stating that his suicide was not an act of cowardice and weakness but of fortitude and heroism (“I do not exonerate him, but the oath I swore to him will endure both bad and good times. (...) After all, he was the Führer of the German Reich. And it is absolutely inconceivable to me to imagine Hitler in a prison cell like this, awaiting his trial as a war criminal, to be judged by foreign judges. Even if he hated me just before the end, it does not change anything. He was a symbol of Germany. No matter how hard it may be for me, I am prepared to take it all on myself just to avoid seeing a living Hitler on trial, no, no, such a thing is completely unthinkable to me.”) Commenting on the potential outcome of the process and the behaviour of his "colleagues", he boasted of the bravery of a doomed man: “How could one do such a cowardly thing just to save his own rotten neck from the noose! To think a German would do such a cowardly thing for a few years of miserable life, for the sake of spending a few more years eating bread to make shit, pardon my frankness! Do you think I would do such a thing to prolong my life? I don't give a shit whether I'm going to be hanged, drowned, die in a plane crash, or drink myself to death! But there must be some idea of honour in this bloody world! (...) I don't give a damn what the enemy does to us, but I do feel bad when I see how the Germans betray each other!” Göring pushed his agenda to the very end, refusing to give in, even to the smallest detail, and refusing to accept the irrefutable facts.

Gustave Gilbert wrote: “In our conversations in his cell, Göring tried to give the impression of a jovial realist who had played for big stakes and lost, and was taking it all like a good sport. Any question of guilt was adequately covered by his cynical attitude toward the ‘justice of the victors’. He had abundant rationalisations for the conduct of the war, his alleged ignorance of the atrocities, the ‘guilt’ of the Allies, and a ready humour which was always calculated to give the impression that such an amiable character could have meant no harm. Nevertheless, he could not conceal a pathological egotism and inability to stand anything but flattery and admiration for his leadership, while freely expressing scorn for other Nazi leaders”.

“The night before the executions, Göring asked the chaplain for the rites of the Last Supper and the blessing of the Lutheran Church. Chaplain Gerecke, sensing another theatrical gesture, declined to administer the rites, telling Göring that since he had never shown the slightest sign of repentance, he would not put on a show for someone who did not usually mean it. The next night, when Goering showed that he had intended to make a mockery of the Last Supper by committing suicide right after it, the chaplain realised how right he was about Göring.

So did I. – For Göring died as he had lived, a psychopath trying to make a mockery of all human values and to distract attention from his guilt by a dramatic gesture.”

The Last Night

The date and time of the execution were kept a closely guarded secret from everyone, including those sentenced. However, apparently, someone in the know was talkative.

The execution was scheduled for 2:00 a.m. on 16 October 1946.

On 15 October, Commandant of the Nuremberg Prison Colonel Burton C. Andrus informed the sentenced prisoners that their petitions for clemency had been rejected. At 9:30 pm, the prison doctor, Dr. Ludwig Pflücker, accompanied by Lieutenant McLinden, a member of the prison guard, came to see Göring, who was held in cell number 5. McLinden did not understand what Pflücker and Goering were talking about, as he did not speak German. Pflücker handed the prisoner a sleeping pill, which he took in the presence of McLinden and the doctor.

After the announcement of the judgment, all the prisoners were monitored with great care and constant checks were carried out. The observers recorded that Göring was lying on his back, not moving, with his hands over the blanket (prisoners were required to exercise discipline in this matter as well). In the records of the military investigation, the guard Bingham testified: “When I looked into the cell I saw that Göring was lying in bed on his back, wearing boots, trousers and a jacket and holding a book. He had been lying motionless for about fifteen minutes, and then he began to move his hands restlessly and put his right hand to his forehead, rubbing it.” The guard Johnson replaced him on the duty: “It was precisely 22 hours and 44 minutes, as I looked at my watch at that moment. After about two or three minutes he (Göring) seemed to go numb and a strangled sigh escaped his lips.”

When the doctor and an officer arrived, Göring was already dead. They found shards of glass in his mouth and an envelope by his bedside. It contained a letter to his second wife, Emma, an address to the German people, and a note to Commandant Andrus.

“Nuremberg, 11 October 1946

To the Commandant

Since my imprisonment, I have always kept the poison capsule on my person. I had three capsules when I was committed to prison in Mondorf. The first one I left in my clothing, so that it would be found in the search. The second I left under the coatstand while undressing and took it again when I dressed. I hid this in Mondorf and here in the cell so well that, in spite of the frequent and very thorough searches, it could not be found. During the trial, I kept it in my high riding boots. The third capsule is still in my little toilet case in the round container of skin cream (hidden in the cream). I had two opportunities to take the capsule in Mondorf, had I needed it. No one in charge of the searches was at fault, since it was almost impossible to find the capsule. It would have been purely by chance.

Hermann Göring

PS: Doctor Gilbert told me that the Control Council rejected the change in the manner of execution to death by firing squad”.

It is still unknown whether Göring wrote the truth or not. From time to time, sensational new information would break the world, such as that Lieutenant Jack Willis, who had the keys to the prison storage room, had allowed Göring to enter and take the poison stored there, in return for his watch and other items.

In February 2005, Herbert Lee Stivers, a 78-year-old former American guard, said that he had met a German girl named Mona while serving in Nuremberg prison, twice handed notes from her to Göring and on the third time he passed ’medicine’, and that she hid all of the “deliveries” in a fountain pen.

The corpse of Göring was cremated along with the bodies of the other executed, and the ashes were scattered in the wind. The letter was, of course, given to his wife. “An appeal to the German people” lies somewhere in the American archives.